‘Who taught them to hide? They never wondered. They were only curious fingers in the dark. You like it? Somadina said, not in a voice that he would use with the girls and women years away, he’d not yet learned to treat pleasing someone else as an act that affirmed his power over them’.[1] Reflecting on the short story by Arinze Ifeakandu, ‘Happy Is a Doing Word’, already published in the Kenyon Review May/June 2022 Vol. 44, No. 3, 45 – 66 and now in the UK publication of the author’s book God’s Children Are Little Broken Things (page references in footnotes are also available to this edition).

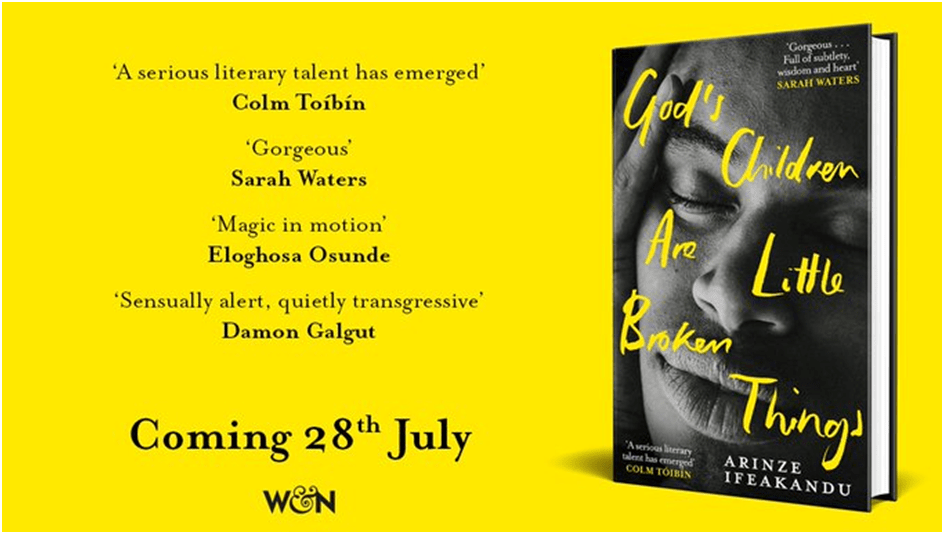

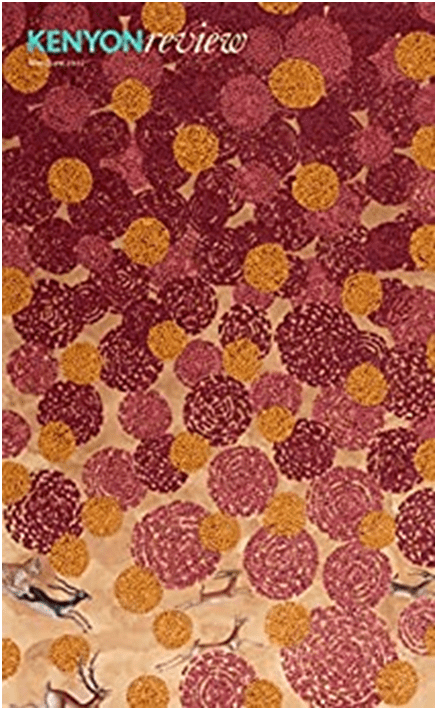

I discovered this book looking at the programme for this year’s Edinburgh Book Festival and I fully intend (booking system willing) to be there when Colm Toíbín interviews this exciting new author in that space. At the moment I have accessed only one short story from the publication, because it is available in Kenyon Review for May/June of this year.

But even this one story offers enough to see that this author is not only doing major new things with intersectional stories of black and queer life but that his innovations extend to exciting new ways to create sentences that also and even combine other languages and dialects, with all their inequalities of conventional status. Of course I love it that the beauty of written sentences is again receiving attention, for these sentences would be great even if they did not show us that it is necessary to understand diversity in languages to understand fully diversity in the shaping of human consciousness. The languages I speak about include those dialects proper to languages refined for formal use, ‘texting’ on social media or idiolects and ‘slang’ created to speak in known company, as well as the language of commerce. Sometimes, well, the language has meanings I cannot always be sure I know as in the speech act of one character below, taking the transliterated (I suppose) form of ‘E go be’. Here are examples of the polyglot nature of the experience of the characters in the novel and its narrator:

She spoke Igbo to Nnandi, persistently, even though he responded in pidgin,..[2].

Whenever his father got this way, he slipped into an elevated Igbo, untouched by English and garnished with the …. occasional unfamiliar word.[3]

… his classmates spoke Hausa, which he did not understand, at break time.[4]

[Speaking to his ‘fuckbuddies’], {Binyelum} …lied to them all the time … to avoid being known, because to be known was to be invested. …after they’d fucked … he would feel only encroachment, the air too suddenly soft with feelings. He would hurry into his jeans and say E go be, like he always did, and leave.[5]

But most of the effects are those denote innovations in sentence structure defined by a new purpose as a storyteller, such as motivated Jane Austen and still motivate Colm Toíbín. Here is an example from Ifeakandu (not necessarily the best, even from this one miraculous story).

Baba Ali’s new woman stayed, night after night, month after month. She set up a light-yellow kiosk under the dogonyaro tree, MTN, Everywhere You Go, it said on the body of the light yellow kiosk from which she sold recharge cards and milk and soap and egg rolls that were soft and sweet, and when the children congregated under the tree to sing to the birds, she shooed them away, the children; in the mornings and afternoons and evenings, women gathered there, talking, laughing, sometimes quarreling (sic,) loudly, so that people rushed out of their compounds to gawk at them and point fingers.[6]

I include the picture above because this tree is an important locus for events in the story. It is first introduced as the:

tree across the yard under which they often sat, watching birds. … One day, he [Binyelum] said, he too would fly, and he would not fall. / Binyelum and Somadina and the other neighbourhood children used to sit under this tree and sing to the birds – …[7]

We need this initial context because the sentence I want to look at deliberately repeats a phrase from it ‘and when the children congregated under the tree to sing to the birds’ recalls ‘Binyelum and Somadina and the other neighbourhood children used to sit under this tree and sing to the birds almost verbatim. That is important because the crux of the repetition and similitude is to introduce and dramatise that passage of time, whilst allowing repetitions and maintaining quotidian and habitual behaviours also changes them, often violently, though the violence is muted. However, the repetition also ensures we feel the disruption of historical change. Read this part of the long sentence: ‘and when the children congregated under the tree to sing to the birds, she shooed them away, the children’. The effect of this is to show that something uncomfortable has occurred in the history of the neighbourhood. It is caused I think syntactically by the belated qualification (really a clarification of an ambiguity in the earlier part of the sentence) which substantiates the external reference of the pronominal ‘them’ (since it could apply to either ‘the birds’ or ‘the children’) as ‘the children’. The discomfort this causes in a reader’s expectations of the flow of meaning is to take us back to the phrase from the beginning of the story in which the two boys childhood seems similar and less intruded upon by adult life: its ‘talking, laughing, sometimes quarreling (sic,) loudly’ and the business that maintains social conformity like ‘gawking’ and pointing fingers’ at errant behaviour. This is, as I have tried to analyse it, very fine writing wherein sentence structure enacts the structure of feeling experienced in and about passing time, repetition and disruptive change.

The sentence regarding Baba Ali’s ‘new woman’ is itself a means of showing how a change habituates itself in ongoing time, emphasised by the phrases which modify the verb ‘stayed’ become necessarily experiential, as if showing the felt elongation of duration of the ‘new’ with which children experience time: ‘night after night, month after month’, as if it will never end nor revert to a past more stable state of well-being. A similar effect is created by the use of the conjunction ‘and’ in the phrase, ‘in the mornings and afternoons and evenings’. It is not that we have one ‘and’ too many here for all are necessary to make us experience the feeling rather than just the fact of passing time and habituation to change.

What is new and contingent, like a new woman and her new business venture, becomes fixed in continuing history, just like the effect created in the sentence by the noun-phrase, ‘light yellow kiosk’. Its brashness (the thing and the expression) becomes habituated and, though still brash, has replaced earlier associations for what used to occur under the ‘dogonyaro tree’. And the sentence uses its careful disruptions to emphasise again a ‘loud’ visual disruption in time in which words, phrases and ‘logos’ mix with products sold as commodities that have no association which each other; a point emphasised by the sudden shock we feel when the qualifying phrase ‘that were soft and sweet’ seems momentarily to apply not only to the ‘eggs rolls’ mentioned immediately before them but also ‘the charge cards and milk and soap’. Those insistent conjunctions throw us – for what they in their insistent multiplicity (for grammatically they are not all expected to be there – rather we want ‘recharge cards, milk, soap and egg rolls that were soft and sweet – conjoin are not associated with each other except as random commodities. That is perhaps an effect of the feel of historical change that cannot easily be accommodated either socially or psychologically. It registers the discomfort of ‘the children’, as both they and the past childhood of the observing adults are ‘shooed away’ into the limbo of lost time.

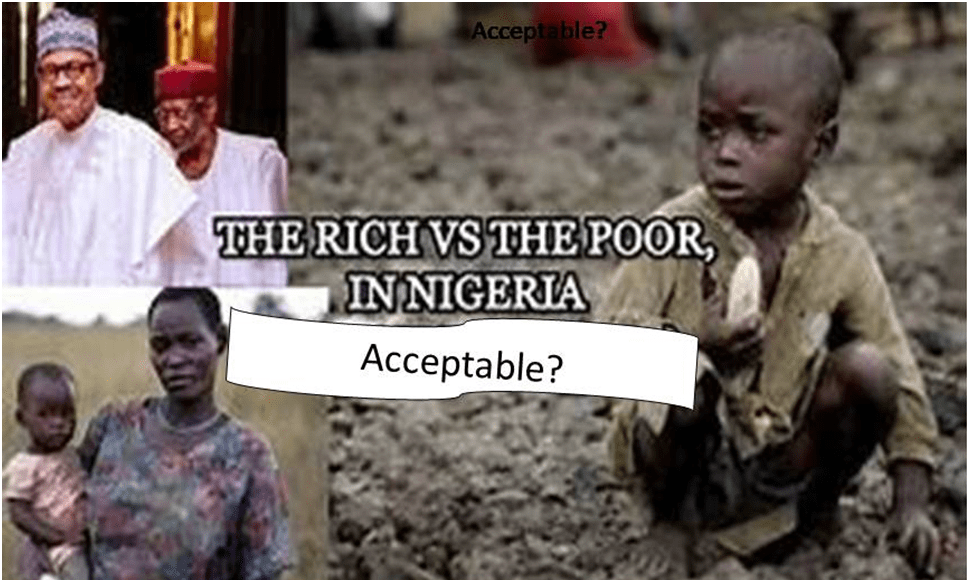

I think it is possible to deduce from the above that this passage deals with how memory and desire mutate in particular space and time in the very act of being recalled by contingent events that occur in the same space current to the characters’ observations of it. In a sense it relates too to the violent changes in Nigerian life that occur with increasing frequency and severity of impact as Nigeria changes and as the boys, Binyelum and Somadina change too. As the country descends into the experience of internal political terror the boys change both psychosexually and socio-psychologically. Those changes include the necessity of new choices related to contingencies that have an impact on each boy’s development from boy to man such as educational opportunities or otherwise and access (including structural discrimination) to work opportunity, as well as (importantly here) important variations in choice of sexual expression and sexual or amative objects.

All this is a possible outcome of a close (and more insistently conscious) reading of the passage because its referents such as the dogonyaro tree are part of the ‘compound’ owned by an absentee neighbour of Somadina, Baba Ali. In this place the two boys go to experiment with each other sexually. In a sense they ‘hide’ those experiments but in another sense they do not, for they are innocent of why public gaze on their sexual play might endanger them. That is the point of the passage excerpted in my title:

They returned there most days after school, making up excuses to wander off from the company of other boys. Baba Ali’s was the perfect spot, that yard with the dark, quiet house whose windows seemed permanently shut to the world. … no kids running around outside under the mango tree with branches that stretched to the dogonyaro tree, forming a vast canopy for all those abandoned cars. Who taught them to hide? They never wondered. They were only curious fingers in the dark. You like it? Somadina said, not in a voice that he would use with the girls and women years away, he’d not yet learned to treat pleasing someone else as an act that affirmed his power over them. He asked because he wanted to know, and Binyelum said yes, and it was not a performance of surrender at all; this was not a game of owning and being owned, not yet.[8]

In this passage ‘hiding’ is almost incidental and an effect of a series of association of an asocial space covered from social presences and their eyes, even the windows which are the eyes of houses are ‘permanently shut’, abandoned cars and trees with ‘cover’ up activity without the need or agency of feeble excuses. Are these boys taught and do they learn to hide. If so, it is not done at all consciously and like the sex it covers it has an innocence – not of the body, which the boys expose to each other’s eyes and fingers and evaluations of what is likable or not. What it lacks is the performative aspect of adult sex in which the person enacts a role for the purposes not of mutual pleasure but power over the other. In this passage that perspective comes from a difficult to determine but authoritative source from Somadina’s future self. Is this just an effect of having an omniscient narrator or does it involve the point of view of an older Somadina looking back at this boyish sexual play with his friend through his knowledge of what heterosexual sex has become for him as a grown and developed adult.

The impetus to hide sexual play only becomes apparent to the boys on its enforced disclosure to the bullying Nnamdi to whom what those two do at Baba Ali’s looks ‘suspect’ for the latter has been ‘tainted early by the world’s caprices’ and who hence knows, and will enact in his own person the ‘shrewd, untrusting nature of the world’.[9] If so there is something of loss expressed at that transition in his historical biography. Nnandi and the gang he leads use that superior knowledge, if tainted and tainted because it needs to feel superior, to hound ‘them like a potent cloud, taking their break money, sending them on errands, making them race each other so that he could see who the man was and who the woman’ (my italics).[10] The key word here is ‘potent’, for it is potency in every sense that adult perspectives seek – whether sourced economically, by hierarchical status or notions of gender (for women are just assumed to be impotent in the sense males think of it).

Somadina grows up ‘straight’ but has an almost unconscious yearning for the ‘innocence’ of his sexual pleasures as a boy mutually with Binyelum. Binyelum grows up gay but without the ability to emotionally attach to another as he had with Somadina. From the latter he moves to letting ‘Dave, a boy from school, suck his dick … when his parents were at work, the doors bolted shut, the curtains drawn,…’.[11] This sex is full of the fear of the hidden and degraded as in the scene where Dave squats ‘secret and safe’ except from the ‘eyes of God’ (for this is in a church) on ‘tiles that looked brownish with accumulated grime futilely scrubbed’. The passing of time here has become merely the habitual accumulation of dirt the literal colour of shit, which in itself sullies the sex they presumably have there: ‘secret desire were too abominable for God’s grace’.[12]

Binyelum however discovers what Somadina never will – the truth that what Nigerian society calls ‘development’, whether social, economic or personal, is always a cover for the maintenance of the inequalities, largely of power:

He’d begun recently to think that the forces of life were capricious and fickle; why, he wondered, did some people spend their lives struggling to scrape by while others wallowed in abundance?[13]

In these circumstances unknown Nigerian men die has either had AIDS or ‘died of loneliness’.[14] In either case it is an effect of deprivation and inequality of opportunities in a corrupt society which is becoming more corrupt and disjointed. Even the hateful boy, Nnamdi, does not deserve the ‘shame’ of his death beaten to death by rough soldiers until he is ‘onion purple’.[15] At first, Binyelum though uses political insight in ways that serve his self-interest, wanting to be the one ‘looking down at everything’ and ‘be the person who told others’ when their desires might be fulfilled.[16] It is only when he realises that this perversion results from the denial of his sown sexual desire that he accepts vulnerability again. He finds with Innocent (a beautiful name for a queer man) what ‘he’d missed’: ‘the warmth and solidness of a man’s body’. Having found that Innocent brings Binyelum back to peace like that of his early youth: ‘guiding’ his ‘head onto his lap, where he cradled it like he would a sleeping child’.[17] But such moments are rare. For the conclusion of this story is much what i earlier said of its treatment of passing time. Development is not a benign force in unequal societies. Binyelum will not ever not fear, whilst in intimate contact with others; ‘encroachment, the air too soft with feelings’, even with other men. The final lines of the story are bleak: ‘Every day he lived, he felt less like himself. Growth, people called it; he thought of it as estrangement’.[18]

I read this story with joy: most of all when it is at its most stoical about the acceptance of oppressive realities. That’s because, I think, it is a story that carries its own remedy for the misery it spreads – awareness that adult realities are constructs, often built from myths suiting the needs of those with power in the status quo. We do not always need to preserve those oppressive structures. We must not allow them to pass themselves off as the definition of ‘forever’.

All the best

Steve

[1]Arinze Ifeakandu (2022a: 47) ‘Happy Is a Doing Word’, in the Kenyon Review May/June 2022 Vol. 44, No. 3, 45 – 66 & Arinze Ifeakandu (2022b: 27) ‘Happy Is a Doing Word’, in God’s Children Are Little Broken Things London, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 25 – 44

[2] Ibid(a): 49, Ibid(b): 27

[3] Ibid(a): 51, Ibid(b): 29

[4] Ibid(a): 54, Ibid(b): 31

[5] Ibid(a): 66, Ibid(b): 34

[6] Ibid(a): 50, Ibid(b): 29f.

[7] Ibid(a): 45, Ibid(b): 25

[8]Ibid(a): 47, Ibid(b): .26f.

[9] Ibid(a): 47, Ibid(b): 27

[10] Ibid(a): 48, Ibid(b): 27

[11] Ibid(a): 50, Ibid(b): 29

[12] Ibid(a): 51, Ibid(b): 30

[13] Ibid(a): 53, Ibid(b): 32

[14] Ibid(a): 54, Ibid(b): 33

[15] Ibid(a): 61, Ibid(b): 40

[16] Ibid(a): 62, Ibid(b): 40

[17] Ibid: 63, Ibid(b): 42

[18] Ibid: 66, Ibid(b): 44

3 thoughts on “‘Who taught them to hide? They never wondered. They were only curious fingers in the dark. You like it? Somadina said, not in a voice that he would use with the girls and women years away, he’d not yet learned to treat pleasing someone else as an act that affirmed his power over them’. Reflecting on the short story by Arinze Ifeakandu, ‘Happy Is a Doing Word’, published in the ‘Kenyon Review’ May/June 2022 Vol. 44, No. 3, 45 – 66.”