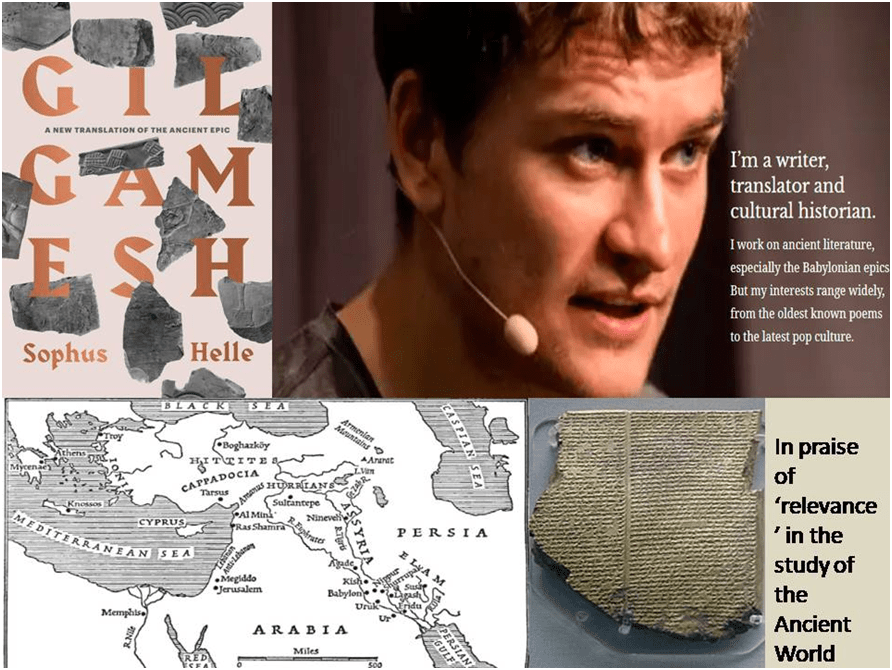

Sophus Helle, in a new translation of the ancient poem Gilgamesh, speaks of the controversy surrounding descriptions of the relationship between its hero Gilgamesh and Enkidu since Thorkild Jacobsen in 1930 (using a word with at the time a relatively brief history of forty years) first called it a ‘homosexual’ one. Helle stresses instead that despite the one explicit reference to physical sexual attraction in the later, and perhaps unrelated Tablet XII, that the relationship’s participants ‘do not explicate the nature of their feelings for one another. …, it is as if they want to leave their bond undefined by words, shapeless in all its intensity’.[1] A reflection on Sophus Helle’s book, published in 2021, A New Translation of the Ancient Epic, GILGAMESH, with Essays on the Poem, its Past and its Passion New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

I am not sure after considering the issues regarding sexuality that Sophus Helle discusses in the ancient text of Gilgamesh that I have in the past sufficiently understood them or how they relate to some of the choices he makes in translating that poem differ from ones made by past translators. This is how I pre-empted my blog in my last one on The Leather Boys (available from this link).

My next blog is in The Epic of Gilgamesh, an undoubted ancient piece known possibly to Homer, if he existed, and whose portrayal of the Achilles and Patroclus relationship in The Iliad is thought by some to a tidier, more civilised version of the love of Gilgamesh and Enkidu (though not by Sophus Helle).[2] In Table XII which reprises a version of the story but with, this time, Enkidu married to a woman before he ventures his life to regain Gilgamesh’s playthings (a bat and ball) from the Underworld. Thence lost his form is recalled only by divine intervention. Asked by Gilgamesh to explain the ‘laws of the Underworld’ (of death in short) Helle translates one of those laws in Enkidu’s mouth thus:

“My friend, my penis, which you touched to please your heart,

is being eaten by a moth, like threadbare cloth.

My friend, my crotch, which you touched to please your heart,

is filled with dust, like a crack in the ground”.[3]

There is no room in such directness of address to bodily pleasure unregulated by social restraints for identity politics or anything but rejection of a world of norms which, as in the Underworld perhaps, police queer pleasure.

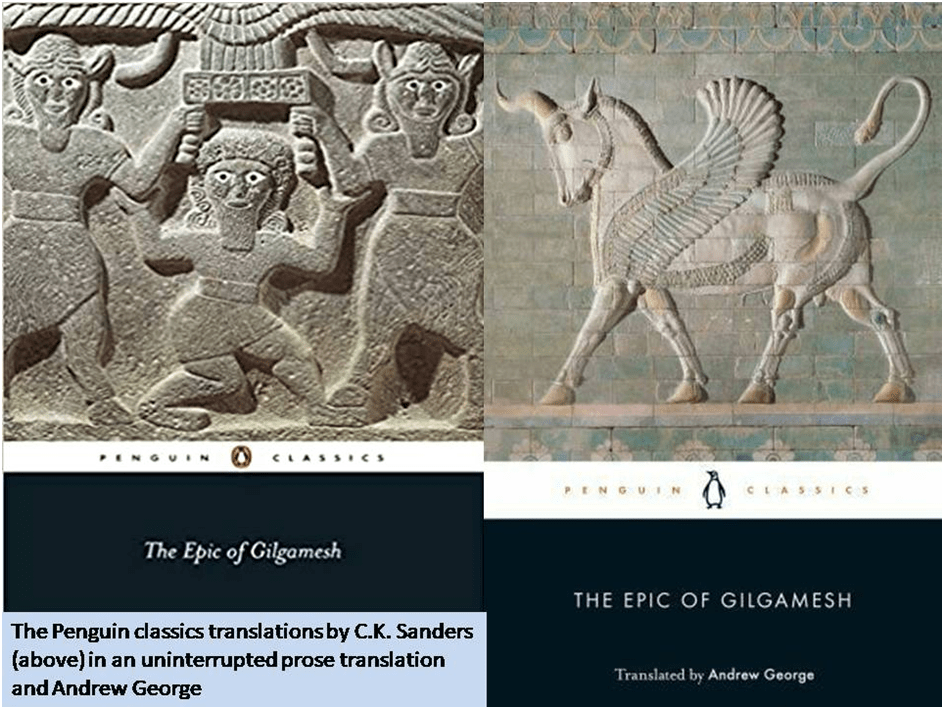

Yet the very translation cited above is contested by the evidence of other scholarly translators’ attempts at the same piece. This, of course, merely illustrates a point Helle makes, in the essays that follow his translation, about the complexity caused by the ‘mess of conflicting variants’ of the poem’s parts (even of its possible sequence as a narrative) and substantial changes in the Akkadian language between the many variants of the text that are extant from Babylonian and Sumerian sources.[4]

There are complexities too that derive from the evolution of the language into demotic and literary forms (the first used for cuneiform text scribal education) from which the often difficult-to-distinguish surviving fragments of text derive. The literary language uses ‘verbal games, puns and assonances’ and sometimes even meanings embedded in the homophonic and visual similarity of words with different meanings.[5] Hence that piece I quoted from Helle’s version of Tablet XII, which other translations omit as separate (N.K. Sandars for instance)[6] or translate as a separate fragment (Andrew George), have a very different interpretative range. Here is Andrew George’s translation of the four lines:

“[My friend, the] the penis you handled so your heart rejoiced,

[the penis like an] old beam do grubs devour.

[My friend, the vagina] you felt so your heart rejoiced,

[like a crack in the ground] is filled with dust.’[7]

The difference in the George translation is that it generalises genital sex acts and does not indicate that it is Enkidu’s penis (‘my penis’ is the phrase used when the shade of Enkidu is the speaker) that is being referred to as a loss to Gilgamesh were he to die. Moreover the generalisation in the George text is about the loss of sexual contact that makes him rejoice but it is a loss of both the physical vagina as well as penis. Helle translates that word not as vagina but ‘crotch’ (indeed ‘my crotch’ making that reference to Enkidu’s own ‘crotch’. Crotch is not a gendered word, whereas vagina is in its Latin root. Moreover, by virtue of its referent in the physical world it symbolises, it could be thought, the biological ‘sex’ of a person. A crotch refers to any area where an organism or object branches into two projectiles, such as the legs at the lower torso in a male or female body or a stick, and is used today to name the front of the underwear for either and both sexes. Helle’s use of the term allows the crotch to be a reference by Enkidu to his own lost body but loses its clear resonance with the image of the ‘crack’ or fissure implied by the metaphor, unless there is a reference to anal or Intercrural sex acts.

George however seems to be implying that the meaning is like that in Marvell’s To His Coy Mistress but applied to physical congress between men and women.

The grave’s a fine and private place,

But none, I think, do there embrace.[8]

The lines as translated by George can be totally absorbed into a heteronormative paradigm, since the penis mentioned is not assigned to anyone and could indeed refer to Gilgamesh’s own organ. Helle gives no reason for his choice differing from that in George. Moreover, I can find no way of researching it being ignorant of even the basics of the languages involved. Helle has however written a significant paper (in 2018) on issues of gender in philological matters, including a reference, concerning another matter, by Andrew George to the translation of the non-binary term kulu’u used in reference to a king:

“The insult becomes sharper when one considers that a kulu’u, if he was like an assinnu, took the female role in homosexual intercourse.” Apart from the view of the “female” role in homosexual intercourse as naturally insulting, which George seems not to question, the statement shows a perceived sameness between the ancient terms can be used to stretch the evidence from one to another’.[9]

Helle insists that by using modern terms and notions (and perhaps values) to interpret ‘ancient categories’ of person that whose characteristics are no longer known, in any exact way to us, necessarily glosses over ‘differences between them’. Thus the scholar, Gabbay, in 2008 could narrow down (their term) the term gala to mean “pederast, homosexual, transvestite, eunuch or the like” since there is, in their view (but not mine or Helle’s) “a clear connection of course between the first three terms” (Helle’s italics in both cases). Thus, even the modern meanings of some non-binary terms can be thought to indicate the same identity quite ignorantly but as if, ‘of course’, it were a mere matter of shared norms. And so, it may be a matter of shared norms, but of norms that intentionally exclude, marginalise, reduce and ‘other’ persons considered outside those norms.

It would seem from Helle’s 2018 article cited above that Helle not only embraces the use of ‘queer theory’ in philological matters but is pointing to a cultural deficit in the mainstream academic traditions in philology and translation. He summarises this ‘deficit’ (as I see it) thus:

The underlying assumption that whatever non-binary behaviour is evinced by ancient individuals is nothing but a cultural surface beneath which hides a “true”, knowable, biological male sex, has distorted the readings of the ancient texts in a number of ways. …

… biological sex is treated as an unchanging essence and cultural gender as a mere surface. Sex is reality, gender is appearance, and accordingly any movement across genders is repeatedly reduced to a “simply,” an “only”, a temporary “role-play”. …[10]

Whilst the harm done by such practices is not said to extend beyond oversimplifying the nuances of Near Eastern ancient cultures and their art, the damage in terms of distorting the view of sex/gender differences is pertinent at other and contemporary levels. These might include exposure of such biased knowledge bases to non-binary students of Ancient poetry and language at the very least or those ‘general readers’ of classic literature who need to understand such distinctions in human difference for other reasons, even in living their lives as responsible ethical agents. In a 2020 paper, Helle advances on this proposition by showing that some ancient texts, looked at from the perspective of queer theory can be seen to have assisted in the creation of a world where a totally ideological ‘violent separation and hierarchization of genders’ is created that prioritises discourses antagonistic to communal and empathic feeling.[11] In this paper he gives indeed a very useful definition of queer theory which can be readily adopted I think by anyone:

Queer theory is based on the assumption that the gender binary (the rigid division of the human species into two and only two genders) and the social predominance of heterosexuality (including specific assumptions about what sexuality entails in terms of identity, power and erotic practices) are not biological constants, but vary across cultures.[12]

Indeed in this paper he is critical not only of mainstream approaches but even those from the same queer theoretical perspective he adopts in the paper that only applies that theory to texts ‘appropriate’ to it – those that Neal Walls, for instance, in 2001 assumed rightly or wrongly to be already complicit with deconstructing “modern Western dichotomies of sexual/platonic love and hetero-/homo-eroticism”, such as, in Walls’ view, Gilgamesh.[13]

Helle calls Walls’ reasoning ‘flawed’ because, in the same way as traditional approaches usually antagonistic to queer theory, cannot ‘be taken for granted’ even if our assumptions are critically radical. We cannot use theory of any kind to prove its own tenets by selecting a text we think has the ‘same’ outlook but must test the theory against ‘the value of the insights it yields’ by texts that may not, in their surface narrative look appropriate, such as the story of Gilgamesh and Enkidu does to Walls.[14]

It is in the context of this discussion that the choice of competing translations of Enkidu’s vision of the ‘rules’ or ‘laws’ of the Underworld with regard to pleasure-motivated genital sex apply. Clearly Helle’s translation, unlike Andrew George’s is in line with the assumptions of queer theory as we have seen them and this is why a non-binary term like ‘crotch’ in Helle is preferred by him to ‘vagina’ in George. Whether this is validated philologically I have already said I cannot know but I am inclined to trust Helle’s scholarship here. In his essays appended to his translation, Helle points to his section as ‘evidence’ that the relationship of Gilgamesh and Enkidu ‘seems to be explicitly sexual’ but does not use strong language to enforce such a conclusion even here, and especially since he shows us that this is the ONLY evidence for driving the debate about whether their relationship is, as Thorkild Jacobsen suggested in 1930, ‘homosexual’ to a positive conclusion.[15] And this again might be a rebuke to Neal Walls for Helle insists on two issues.

First he insists that the means by which they refer to their relationship directly to each other are vaguely posed and likened to the fact that they never use each other names in each other’s company and never ‘explicate the nature of their feelings for each other’: ‘as if they want to leave their bond undefined by words, shapeless in all its intensity’. The sense that there are no norms (and hence categorical names) for labelling this amorphous intra-/inter-personal thing is conformable to a queer theory that makes no assumptions based on categories not applicable to the instance. Second, he insists that the term homosexual ‘might not be the right words’ for the ‘heroes having sex’ even if a new fragment of the poem is found that describes such mutual sex. This is because, as queer theory insists too, ‘Men could have sex with each other, but that did not make them homosexual, it is not an identity or a fixed role in society’. We need not though abandon the erotic charge of the poem because the identity of the characters cannot be attached to a modern or ancient label.[16]

Instead Helle attempts to use the terminology of the text to describe the relationship without evoking expectations of what that relationship might be like. In line with the allusive ambiguity of the poem’s language, as Helle sees it, are the terms used, which in these essays includes one discovered, in Helle attribution, to Neal Walls, whom we have seen him previously critique as over-simple in his meta-critical thinking. That term is one applied in individual persons to the erotic, cognitive and emotional agency of kuzbu, which Helle translates as “charm” but which is thought actively to draw others to its possessor: a ‘kind of magnetic pull’. The priestess (George and other translators translate her role as ‘harlot’ quite shamelessly) Shamhat says of Gilgamesh to Enkidu:

Let me show you Gilgamesh, this man about town.

Look at him, see that face:

The dignity he has, the beauty of youth!

His whole body is full of charm (kuzbu).[17]

The other words Helle highlights describe not persons but the nature of the relationship itself as a combination of attraction and aggression including liking, likeness, comfort, combat, friendship and violence. These include the verb issabatū meaning both to hold as in wrestling and the hold that is ‘an affectionate embrace’. Another term is the noun (seen first, says Helle, by Ann Guinan and Peter Morris) meḫru. This term is endemic to militarized societies and means:

something like “match” in its broadest possible sense. Two equally long lines of a geometrical diagram are each other’s meḫru, a tablet copied from an original is the meḫru of that original. Among humans, a meḫru can be a social peer but also a rival.

…

…. Ninsun declares (Enkidu) Gilgamesh’s equal, again using a form of the word meḫru. The epic repeatedly stresses how similar the two men are: …

The young men of Uruk elect Enkidu as their champion to fight Gilgamesh because of the king’s autocratic ways: “… a partner (meḫru) was chosen as if he were a god.’ This could mean, Helle goes on to say, that Enkidu is chosen as an enemy, such as the monsters in their nation’s mythologies who test kings, or a kind of sacred bride, as priestesses were chosen to sleep with gods; in short; ‘Gilgamesh’s lover’.[18]

I think what Helle does superbly here is to queer the relationship between the two men by showing the means by which an ancient culture, and texts from that culture, could inscribe within them issues that exceed local expectations and norms, without depending on identity labels that limit either character or relationship. This equates these excesses with those of the dreams they both have and both offer to each other for interpretation or to delineate future possibilities and their alternatives for their future(s). Most importantly it takes the given of a militaristic and obsessively hierarchical social framework and plays with it to imagine notions of equality between persons that were in the everyday reality of that culture totally unthinkable, whether in the governance of state, in war or in the roles taken in love and sex.

This applied even, it seems, from the evidence of ‘omens’ from other cuneiform texts to anal sex: ‘One omen states that “if a man has anal sex with a social peer (meḫru), that man will become foremost among his brothers and colleagues”’. The implication of this is that equalities only produce more socially hierarchical inequality:

The idea of males having sex with each other irrespective of power is simply not entertained: their social relations to each other, to their colleagues, and to their family will always be central to the act. (As Oscar Wilde is said to have said, “Everything is about sex, except sex, which is about power.”)[19]

Oscar Wilde is cited here but the whole of Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II and Derek Jarman’s film version of that play too could have been cited likewise, though neither is as pithy and to the point.

This is a very great and readable poem in a tremendous translation, once you come to terms with the conventions it uses to show omissions based on damage to the cuneiform tablets. The essays are brilliant. But the poem lives as well because Helle is also a climate activist and his treatment of the poem’s ability to critique the negative effects of un-counselled power whether in kings, epic warrior heroes or the Gods is worthy of this activity and is relevant, though Helle does not stress this explicitly as he queries why heroes ‘have turned the forest into wasteland’ or the Deluge the Gods bring ensures ‘the past has turned to clay’. [20] The main burden of Helle’s reading of the poem is that humans have nought to do with immortality, eternity or the unvarying. Except that is that they become storytellers and the subject of continually retold stories, when Gilgamesh ‘is nothing but words on a tablet – and that is the price of immortality. To live forever, Gilgamesh must become something that is not quite human and not quite living: he must become epic’.[21] Do read it if you like texts that are not only classics but world-making. This is a good translation fascinatingly interpreted.

All the best

Steve

[1]Sophus Helle (2021: 171) A New Translation of the Ancient Epic, GILGAMESH, with Essays on the Poem, its Past and its Passion New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

[2] Sophus Helle (2022; 137) A New Translation of the Ancient epic Of Gilgamesh with Essay on the Poem, its Past and its Passion. New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

[3] Tablet XII lines 96ff in ibid: 117

[4] Ibid; 128

[5] Ibid: 154

[6] N. K. Sandars (trans & ed.) 3rd ed. (1972) The Epic of Gilgamesh London, Penguin Books .

[7] Andrew George (trans & ed.) 2nd ed. (2021: 148) The Epic of Gilgamesh London, Penguin Books. Tablet XII, lines 96f. […] used by George to indicate passages where words are restored from a break in the tablet using parallel passages and context (see p. xiii).

[8] Andrew Marvell’s To His Coy Mistress Available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44688/to-his-coy-mistress

[9] George in 2006 cited in Sophus Helle (2018:42) ‘“Only in Dress?” Methodological Concerns Regarding Non-Binary Gender’ in Gender and Methodology in the Ancient Far East BMO 10 (2018) (ISBN: 978-84-9168-073-4), 41 – 53. Available at: https://sophushelle.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/helle-2018-only-in-dress.pdf

[10] Ibid: 42f.

[11] Sophus Helle (2020:73f.) ‘Marduk’s Penis. Queering Enūma Eliš’ in Distant Worlds Journal 4, 63 – 77. Available at: https://kileskrift.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/helle-2020-marduks-penis.pdf

[12] Ibid: 67

[13] Walls cited ibid: 66.

[14] Ibid: 67

[15] Helle (2021 op.cit: 171).

[16] Ibid: 171

[17] See including citation, Ibid: 172f.

[18] Ibid: 175f.

[19] Ibid: 176

[20] Ibid: 166 & 191 respectively.

[21] Ibid: 200

3 thoughts on “Sophus Helle, in a new translation of the ancient poem ‘Gilgamesh’, speaks of the controversy surrounding descriptions of the relationship between its hero Gilgamesh and Enkidu since Thorkild Jacobsen in 1930 (using a word with at the time a relatively brief history of forty years) first called it a ‘homosexual’ one. Helle stresses that the relationship’s participants ‘do not explicate the nature of their feelings for one another. …, it is as if they want to leave their bond undefined by words, shapeless in all its intensity’. A reflection on Sophus Helle’s 2021 book, ‘A New Translation of the Ancient Epic, GILGAMESH, with Essays on the Poem, its Past and its Passion’.”