Intent on joining the Merchant Navy with a man called Reggie that he has just learned that he loves, Dick visits a vessel where he meets a group of already serving sailors: ‘ “I love Dick,” one screamed. And they all screamed with laughter. / …/ Dick thought of the ugly, middle-aged powdered faces. He had never seen homosexuals like them before. He had never thought of his relationship with Reggie as being homosexual, he hadn’t labelled or questioned it. It wasn’t like this. They would never be like these men’.[1] A reflection on Gillian Freeman’s book (1961) and film (1964) The Leather Boys.

How do you represent the idea of a gay man? It is a question that has fixated cultures for centuries in the West. In the East, the problem, at least in ancient cultures it has not seemed such a problem and, for this reason, the term ‘oriental’ was once interchangeable in Western culture for the term ‘queer’, although both, at the time I speak would have a negative tinge, or a tinge that felt negative in order to mask or protect from illicit desire for its content – as is clear in the movement in art we call ‘Orientalism’. My next blog is in The Epic of Gilgamesh, an undoubted ancient piece known possibly to Homer, if he existed, and whose portrayal of the Achilles and Patroclus relationship in The Iliad is thought by some to a tidier, more civilised version of the love of Gilgamesh and Enkidu (though not by Sophus Helle).[2] In Table XII which reprises a version of the story but with, this time, Enkidu married to a woman before he ventures his life to regain Gilgamesh’s playthings (a bat and ball) from the Underworld. Thence lost his form is recalled only by divine intervention. Asked by Gilgamesh to explain the ‘laws of the Underworld’ (of death in short) Helle translates one of those laws in Enkidu’s mouth thus:

“My friend, my penis, which you touched to please your heart,

is being eaten by a moth, like threadbare cloth.

My friend, my crotch, which you touched to please your heart,

is filled with dust, like a crack in the ground”.[3]

There is no room in such directness of address to bodily pleasure unregulated by social restraints for identity politics or anything but rejection of a world of norms which, as in the Underworld perhaps, police queer pleasure. These days debate about how you represent a gay man, lesbian or bisexual is being revived from a version of history that is being promoted by a pernicious propaganda group called the Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual (LGB) Alliance as a means of reinstating the unquestioning authority of a binary division of biological sex. In doing so these ‘debates’ are also a tool to break the heart, soul and politics of trans people and those followers, especially but not only in the LGBTQI+ community who have always seen trans and non-binary people’s struggle with norms to be the same struggle as theirs. And it is in this context that I want to return to how the struggles around representation of gay men in particular were demonstrated, and perhaps sometimes forcibly and cruelly simplified to meet homophobic expectations in the years immediately before the 1967 Sexual Offences Act.

From the reflection on reading The Leather Boys (1961) by Gillian Freeman and seeing the film of the same name for which she also wrote the screenplay (1964) I feel that the question itself arises from the inevitably oppressive effect of the need to label sexuality and to validate sexual choices, which comfort the most oppressive needs in ourselves – to pin down what we are rather than accept and deal ethically with what we desire. For the notion of being determined, together with one’s actions and feelings, by an identity is innately oppressive and bypasses ethical decisions. In a real sense that is the meaning of the gender-critical movement, to lay down a false biological certainty, in the form of the binary division of biological sex as they misperceive it, as the root of all behavioural and personal politics. Their alliance with the forces of the right, and the present government, are sure signs of this. But I will now look more closely at the 1960s concentrating entirely of a critical reading of a contrast between this one film and one book, which only on the surface tell the same story and not with the same character.

A major difference of the film from the book was that its most central character – he who opens and closes it – is abandoned in the film’s narrative. The name Dick, because it is perhaps rather too easily translated to crude phallocentricism (and indeed is in Freeman’s novel), is abandoned for a more rock-like and well-known name, Peter. But Peter is also a totally new character; rewritten, in a way that changes entirely the limits within which this gay man is represented in part by differences in how the role of the Merchant Navy is utilised in the respective stories of film and novel. In the novel the Merchant Navy is an important symbolic marker of only one kind of representation of queer men and is never a locus in which we see gay lives being actually lived.

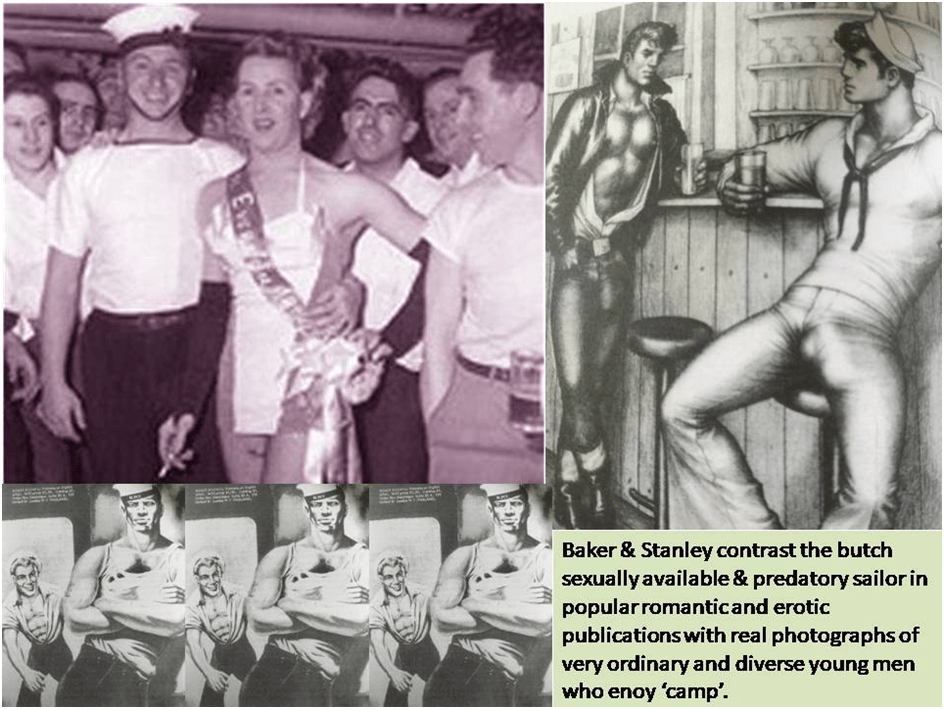

The history of the association of queer life with the Merchant Navy has now begun to be written, brilliantly in fact, by Paul Baker and Jo Stanley, in a book about which I have already blogged. The authors summarise the culture of the Merchant Navy, based on oral interviews as one that is difficult to characterise as one matching popular stereotypes at the time of the horny uber-masculine (‘butch’) and bisexually available (and often sexually predatory) sailor.

The authors contrast those stereotypes with the fact that some men chose life in the Merchant Navy solely because ‘they could enjoy the company and proximity of lots of men, some of which might be available’:

And this is perhaps the most interesting aspect of this history of gay seafarers. Not so much that gay sex went on – passenger ships were places were a lot of sex takes place anyway – but that a large camp subculture was allowed to flourish in such a traditionally masculine territory. It was a situation in which something illegal and reprehensible ashore became an exceptionalised and accepted ‘bit of fun’ to thousands of passengers and seafarers. Butch-femme roles were played out long after such behaviour was seen as oppressive by gay activists ashore.[4]

As one of those activists myself, I do remember the excesses of the stress on ‘negative or sexist images’ of gay men and it is this very debate that LGB Alliance has revived. My feeling now is that that position is incredibly over-simple and based as much on stereotypical thinking as that it pretends to contest. For men went to sea for lots of reasons. In The Leather Boys (both book and film) the Merchant Navy is an important feature in the narrative but yet works very differently in each.

In the novel, Dick, a listless young man who has no wish to find paid work. Dick learns that he loves Reggie, a married man, whom he meets in a coffee bar for bikers. Reggie, though married, has had no sex with his recently married wife Dot for some time and she is ‘seeing’ other men. Dick and Reggie fall into bed tired after a day at the sea for Dick has lodged the now homeless Reggie with his Gran’s, following the death of her husband. Reggie has a job but, tired of the sole social escape from a loveless marriage the biker’s café had provided, agrees to join the Merchant Navy with Dick. These are the circumstances in the novel that take Dick to sign on in a ship already in port whereon he meets some of the Merchant sailors. It is they that make it clear that Dick’s name already has a special meaning for men who have sex with men:

The men gave gave a chorus of giggles and shrieks and the one next to him said, ‘ ‘Ow camp!’

Dick blushed.

“I love Dick,” one screamed. And they all screamed with laughter’.[5]

In the film the ‘Dick’ joke is unavailable and Peter, the already initiated gay man who takes on some of the roles of the character Dick, is already also a member of the merchant navy taking on a temporary life of leisure as a biker., except for casual labour at night. Many narrative strands become different as a result of Dick’s loss from the film’s narratives. The story of Dick’s Gran is transferred to Reggie and it is Reggie who invites Peter to Gran’s after he leaves Dot following a disillusionment with her that seems to have no one clear cause. Even after one night however of experimental sex with Reggie (that is not described), it is clear Dick wants more, though Reggie, shows at this time an ‘apparent indifference’ that can be explained Dick thinks in his self-talk to the effect that: ‘He was just randy. Men do things with other men when they were randy, everyone knew that. It didn’t mean they felt anything special though’.[6] But for Dick, this one nocturnal experience was ‘special’, making him sense or ‘feel’ Reggie’s movements in the bedroom in the morning as a matter of visceral rather than just observational attention:

Dick … had never made love before and he felt a sense of warm contentment and gratitude and affection for Reggie. He longed to put his hand on Reggie’s arm. He looked at Reggie’s arms, strong and muscular, The desire to touch him was almost overwhelming but he didn’t dare and instead turned his head away on the pillow.[7]

This is I think quite a special moment in 1960s queer literature, where Dick feels the motion of a potential lover just as the classic novel had made the reserve of heroines such as Anne Elliott in Jane Austen’s Persuasion who senses her liberation from a bothersome boy-child before she is aware who has liberated her (for she cannot see him): her former lover, Captain Wentworth:

She spoke to him, ordered, entreated, and insisted in vain. Once she did contrive to push him away, but the boy had the greater pleasure in getting upon her back again directly.

“Walter,” said she, “get down this moment. You are extremely troublesome. I am very angry with you.”

“Walter,” cried Charles Hayter, “why do you not do as you are bid? Do not you hear your aunt speak? Come to me, Walter, come to cousin Charles.”

But not a bit did Walter stir.

In another moment, however, she found herself in the state of being released from him; some one was taking him from her, though he had bent down her head so much, that his little sturdy hands were unfastened from around her neck, and he was resolutely borne away, before she knew that Captain Wentworth had done it.

Her sensations on the discovery made her perfectly speechless.[8]

Whilst the literature of heterosexual romantic love might have long dealt with such sensations, Freeman in writing, as she has done, rounds out the nature of represented relationships from the physical (indeed here the sexual though that too Austen could do) to the cognitive and emotional domain of the ‘romantic’. I feel a debt to her for that. It ensures that Dick is continually rescued from the pun inherent in his name that represents gay men largely through physical and genital sex. It belongs too to the sense that it challenges the ‘otherness’ of representations pf men who had sex with men, very prevalent in the period, of the underworld: sinister, criminal and potentially violent. Despite the feminised – in the standards of the time – and infantilised behaviour of the Merchant Navy crowd (with ‘shrieks’ and ‘giggles’) – stands the figure who keeps the ‘queers list’: ‘Big Mary’s on that ship, darling. You’ll ‘ave to do just what she says. She’ll draw a knife if she’s upset’.[9] This very line from the novel is one of the few transposed to the Merchant sailors confronted in the Portsmouth pub in the screen’s screenplay by Freeman. It is said in the film in a scene where Reggie, who has no notion of merchant navy or queer life it seems, is directed to a public house in Portsmouth habituated by Peter’s (the new ‘Dick’ remember) queer sailor chums. These sailors are depicted as sinister and predatory, circling Reggie’s ‘innocence’ and locking it in as if in a vice. It is a most disturbing incident for it is the first moment that Reggie realises that he has regularly been sleeping in the same bed with a man who he now presumes (as we as audience perhaps surmise much earlier) is interested in having a physical sexual relationship with him. This revelation placed at the very end of the film allows Reg to silently re-read the way in which Peter has made himself into a replacement for Dot. The film emphasises this more in that Dot (in the film only) has her own role in the Leather Boys group and had, before her final infidelity to Reggie, re-alighted his feelings and desire for her by travelling pillion with him on a bike race from Edinburgh (her new boyfriend’s bike having broken down).

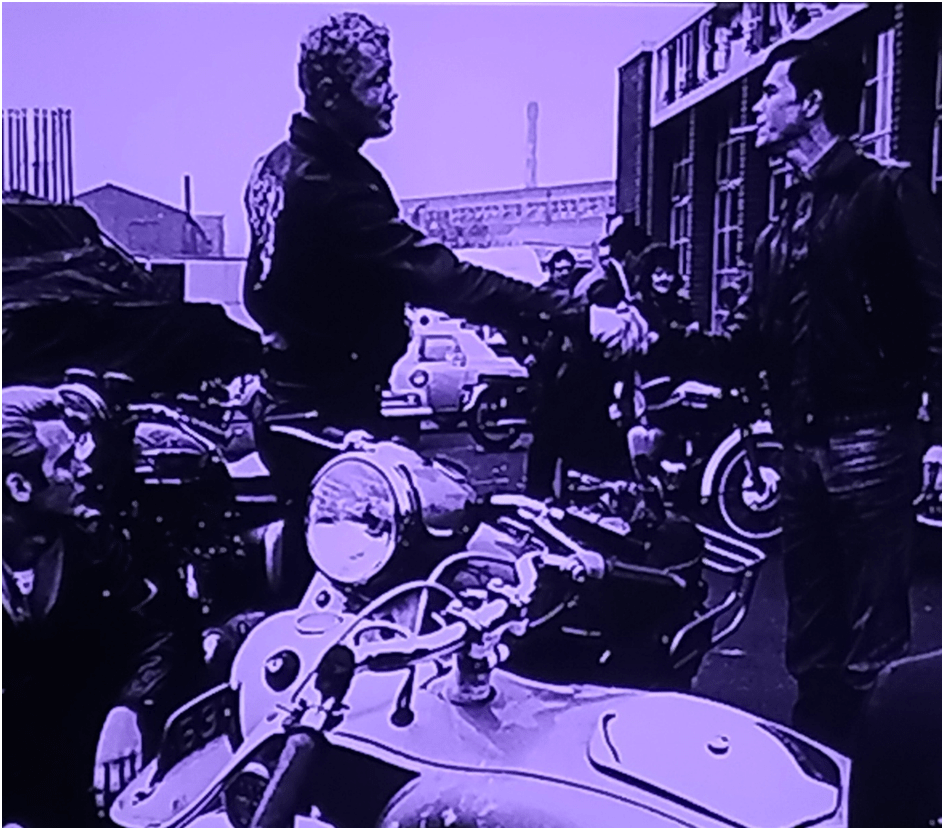

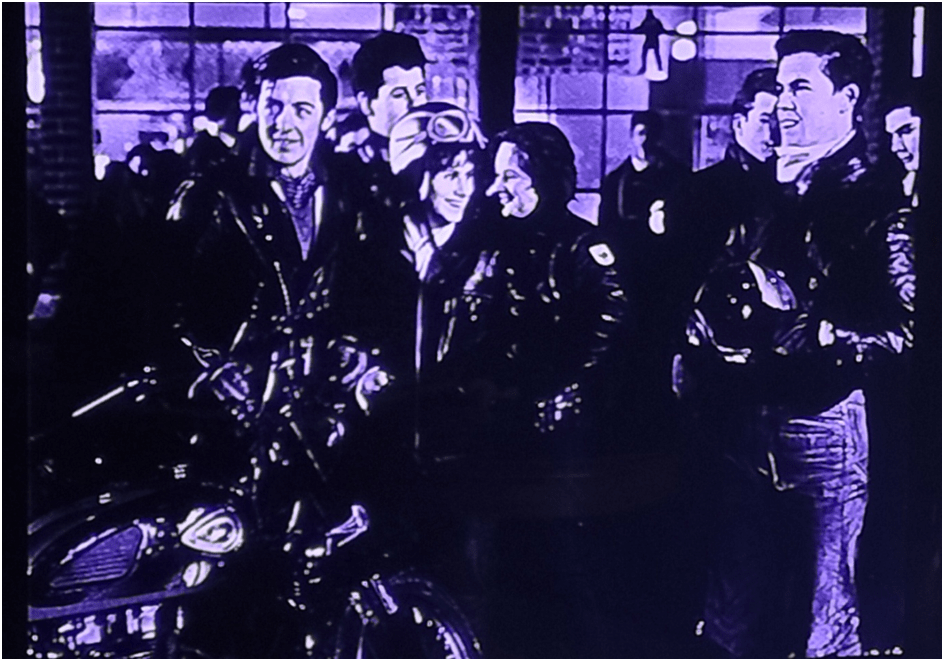

The fact that the Reggie of the novel is never conceived even as a man whom, though heterosexual, might ‘do things with other men when they were randy’ is paramount to the difference in representation between the novel and film, with only the former facilitating the sense of a more fluid general sense of human, and especially male, sexuality that had accompanied the publication of the Kinsey reports. It was unlikely that the idea of an othered sexuality islanded in stereotypical ideas. Those ideas associated queer gay men with the Merchant Navy in the popular mind and with a threat of predation (and corruption) of ‘normal’ males. Reggie in the film (but not the novel) is protoypically represented as the ‘normal male. In the novel it is Reggie alone who is a biker and who wears leather for the purpose, whilst Dick comes to both attributes only gradually – to bikes only by ‘inheriting’ Reggie’s bike on the latter’s violent death. In the film however both men being leather boys is a condition of Peter and Reggie meeting, as in the following still.

The still is beautiful in its representation of masculinity as an ideal of distant meeting between the men, with Peter only compromised by his overactive movement (apart from the very end of the film) and his blond hair, which fails a popular criteria of sixties masculinity. The bikes and factory setting are replete with projectile or erect phallic imagery, even in the firm way Reggie holds a cigarette in his mouth and the distant handshake. The setting is almost insistently masculine thus throughout the film, even though in the film Dot (Rita Tushingham) dons leather and rides pillion.

In the novel Dot never visits the leather café nor does she wear leather ‘gear’. Indeed the latter venue is marked as a men-only-area where bikes and ‘leather’ together signify a standard of male sexuality. Used separately leather gear without a bike signifies laughable half-men: the true leather boys ‘called them “kinky” and “leather johnnies”’, but deign to sell their bodies to them ‘for an easy quid or two’.[10] This kind of flexibility between straight and gay sexuality has no place in the film. It is a symbol of male desirability and power:

It was the café for the boys on motor-bikes. It was like a badge of admittance, the bike and the gear. It gave Reggie his only sense of belonging and being part of society. The gear was made of leather…. It made them feel important. They felt select. … the girls liked to see them in leather, they liked to wear it, to have this feeling of separateness and power.[11]

This passage is in chapter 2. It is only in Chapter 10 when Dick, having found a ‘new dimension’ to his life prompted by the money from the crime instigated by the leather boys’ group but also by his ‘affair with Reggie’, purchases his first ‘pair of leather jeans which he had wanted for weeks’.[12] Freeman seems here to signify that separateness and power – male power of a thoroughly patrician kind – is accessible to a man who is becoming to see his sexuality as only directed towards other men and symbolised by his look in leather and the feel of ‘the slight stiffness of his jeans as he walked’.[13] His distaste for female sexuality (in their kisses, for instance) is conveyed from the beginning by a sensation that recalls the vagina dentata with which psychoanalysis sometimes associated male sexual misogyny: Rose’s kiss appears to ‘draw him into the wet, dark, devouring cavity within’.[14] Looking at Reggie and remembering that very devouring kiss with Rose, sex with Reggie is something ‘he wanted to relive in every detail, … . Afterwards he hadn’t been able to sleep and he thought how different it was from kissing Rose. He would never want to kiss a girl now’.[15]

Freeman makes these comparisons entirely within the experience of a man who will eventually confirm his heterosexuality, or at least rejection of homosexuality, in the screenplay for the film, within the relationship between Reggie, on the one hand and comparisons of Dot and Peter, who both share a bed with him. Look for instance at the comparisons between the upper and lower register of the collage below:

Whilst sex is associated with bed for Dot and Reggie, it is more often felt to be impossible after they are married and sexual congress contains always a sense of distance being actively maintained. Reggie’s hands appear both to embrace Dot and push her off simultaneously in the upper left still, whilst the angle and opposition of their arms and bodies in the upper right still seems almost an icon of separateness of themselves in their luckless marriage. That marriage in the film appears to fail first after Dot dies her hair blond at Butlins holiday camp on their honeymoon. Indeed the pair only get back together – almost – when the effect of the hair dye has been reversed and Dot is again brunette. In contrast the natural blonde, Peter, and Reggie in or preparing in bed mirror each other actions and gestures so that there is conveyed proximity that does not have to be sexual. Yet the appearance of Peter and Reggie in bed apes marriage, as the heterosexual marriage in the film does not. In the novel the relationship Dick and Reggie in bed is sexual on the volition of both. Though even in the novel the relationship is not articulated by either character thinking of themselves as gay, or ‘homosexual’, the fluidity of the dynamic of their relationship into a sexual one is truly well drawn and definitively queer – drawing from situations other people do not see as amative, a true sense of companionship in love.

In contrast Dick attempts to draw from his experience of the Merchant navy ‘queers list’, and even knowledge of the violent predation of ‘Big Mary’, a sense that though he need not label his and Reggie’s love as ‘homosexual’. Moreover the logic of the writing shows that even were they to now think of themselves thus, it would be in the context of knowing that some sexual relationships between men will not make them ‘like these men’ with their ‘high-pitched laughter’. As a result, Dick comes to terms with queer diversity, even as he is seeing those men as ‘awful queers’. For he and Reggie know that in having ‘each other …they wouldn’t have to bother about anyone else’.

Dick thought of the ugly, middle-aged powdered faces. He had never seen homosexuals like them before. He had never thought of his relationship with Reggie as being homosexual, he hadn’t labelled or questioned it. It wasn’t like this. They would never be like these men’.[16]

In being not like these men, Dick renounces female nomenclature too and adopts the masculine stance of a ‘leather boy’ as if at the end of the novel inhabiting the body as well as taking over Reggie’s bike to match his own leathers. The final moment of the novel sees him beginning to relate again with another man, in leather, like himself: ‘each accepting the unspoken challenge’. We might think this challenge is to a race but it might otherwise be for a new kind of male togetherness: ‘both machines roared away in unison, their exhausts clattering and reverberating, the smell of burnt fuel lingering in the air’ (my italics).[17] In my view, it is an ending that shouts about about diversity in queer identity.

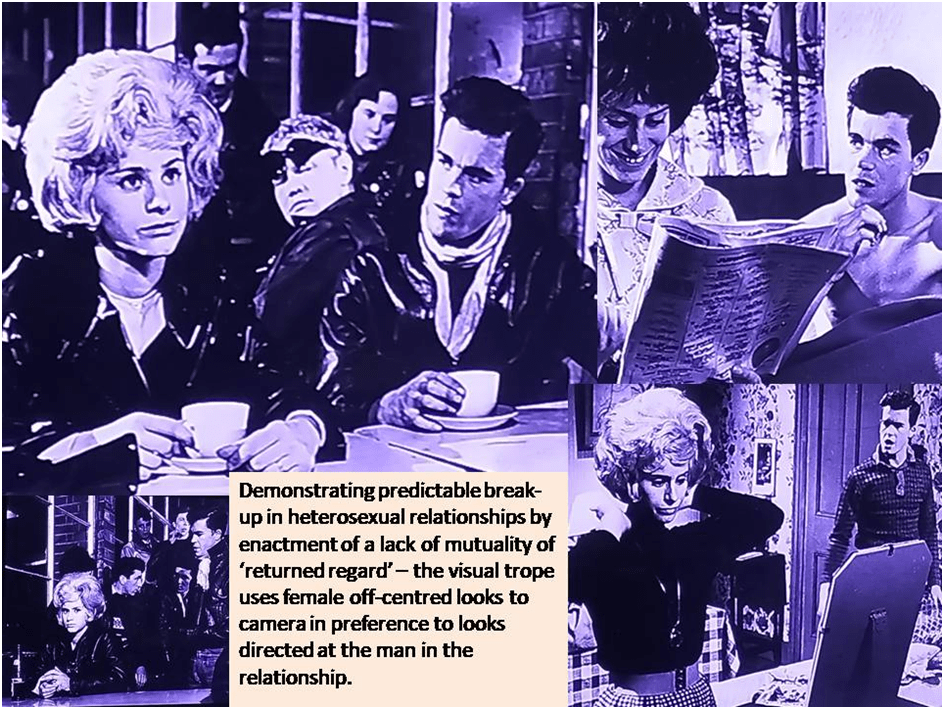

How different from this queer resolution in the novel is the film, in which gay men are stereotyped as potentially always, if not intentionally, predatory, even Peter. The final scene shows that men can only become men anew by accepting loneliness and anomie. In that scene men are represented in ways that previously only the women in the film were. I can illustrate this best by looking first at how the film characteristically deals with Dot’s claim to have a life even just a little independent of a man. Rita Tushingham plays this role brilliantly. Look, for instance, at some moments where she attempts to be assertive in her marriage in the collage below.

Her independence is marked by an emotional distance from her husband that is most often registered by scenarios wherein she does not meet his gaze but looks towards the camera, often in the foreground of the shot, sometimes leaning into the picture frame itself, as happens sometimes in classic art. Reggie is most often backgrounded whilst looking directly at Dot. His regard of her is not returned – hence this is why I dub this behaviour a lack of a mutual ‘returned regard’. The phrase ‘returned regard’ aims to revive the sense in the word ‘regard’ related to physical looking, as in its French root. Dot’s lack of returned regard is sometimes stressed by the actor’s gestural ‘business’ or by the existence of properties including mirrors and windows. The still in the top left above is of primary interest because Peter is regarding both of the partners from behind both but in between them, predictive of his later role as a man who splits them up.

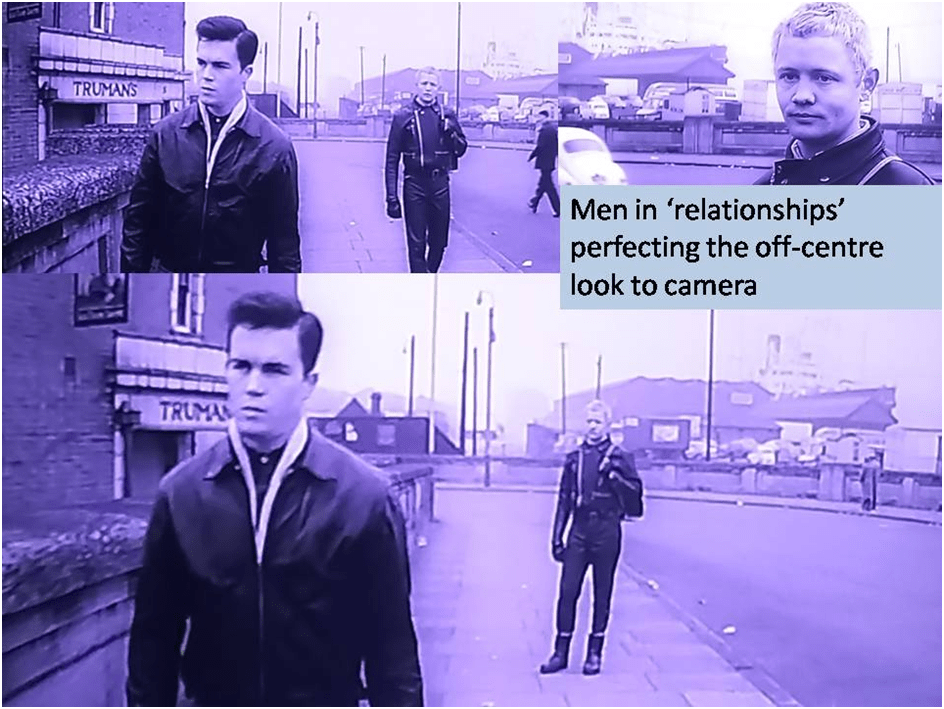

At the end of the film Reggie takes on the role of the one who does not return the regard of others, fearing that the act of looking is an act of possession of him or predation. Examine the stills in the collage below:

Reggie’s look is to the camera with his gaze off-centre in both the still in the lower register of this collage as in the top-left still. In the bottom instance, Peter has accepted Reggie’s refusal to join with him and has stopped tracking him except by his eyes. Thus as the camera moves with Reggie, Peter fades into the distance Reggie creates between them. Reggie has asserted independence as did Dot but unlike her, since she accepts substitutes for her loss, he looks lost (almost existentially so). Women in the film, of course, are represented as insufferably superficial when not manipulative, even Gran, but the same filmic trope here is used to emphasise something about the sadness but dignity of men in their refusal to display emotion (here at least). So, although Peter has clearly shown jealousy of Dot in many earlier scenes, in this scene at the end, even Peter is allowed some dignity, unlike the ‘queens’ in the pub they have left.

So there you have it. In the 1960s representations of queer men and male relationships have clearly been focused entirely differently in each medium and this may reflect the relative size and kind of audience for each art form. But it also reflects the greater ability of the writer, at least in this point in history, to grasp the diversity that characterises working-class masculinity and to refrain from its stereotypes for at least some significant moments at the least. And what both shows is that constructions of gender and sexuality and the agency that leads to choices in social and ethical contexts matter more than ‘identity’, though the latter still matters. I really welcome feedback to the blog at any level in WordPress, Twitter or Facebook (if the latter in my husband’s account).

All the best

Steve

[1]Gillian Freeman (2014: 108-9) The Leather Boys London, Valancourt Books.

[2] Sophus Helle (2022; 137) A New Translation of the Ancient epic Of Gilgamesh with Essay on the Poem, its Past and its Passion. New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

[3] Tablet XII lines 96ff in ibid: 117

[4] Paul Baker & Jo Stanley (2014 reprint of 2003 book: 14f.) ‘Hello Sailor!: The Hidden History of Gay Life at Sea’, Oxford and New York, Routledge

[5] Freeman (1961 op.cit: 108)

[6] Ibid: 70f.

[7] Ibid: 69

[8] Jane Austen (2019 digital ed. of original published in 1818) Persuasion, Chapter 9 Project Gutenberg E-book, Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/105/105-h/105-h.htm

[9] Gillian Freeman (1961 op. cit: 108)

[10] Ibid: 12

[11] Ibid: 11

[12] Ibid: 90

[13] Ibid: 90

[14] Ibid: 19

[15] Ibid: 72

[16]ibid: 109.

[17] Ibid: 135

One thought on “‘ “I love Dick,” one screamed. And they all screamed with laughter. / …/ Dick thought of the ugly, middle-aged powdered faces. He had never seen homosexuals like them before. He had never thought of his relationship with Reggie as being homosexual, he hadn’t labelled or questioned it. It wasn’t like this. They would never be like these men’. A reflection on Gillian Freeman’s book (1961) and film (1964) The Leather Boys.”