Towards the very end of this novel a man in the Highlands above Glasgow gives the bedraggled, abused and self-alienated young Mungo Hamilton a lift in his Defender Land Rover as he treads back towards Glasgow. The man talks of one of his own four sons: ‘“Gregor’s a good lad. … Always helps his mother around the house without being asked, but he’s a wee bit …” The man paused as though he couldn’t find the correct word. “Artistic. T’cbut. Do ye know what I mean by that?”’[1] This is my blog review of Douglas Stuart (2022) Young Mungo London, Picador.

BEWARE: IT CONTAINS SPOILERS. DO NOT READ BEFORE THE NOVEL IF THIS WILL SPOIL YOUR PLEASURE OF IT (AS IT WOULD HAVE MINE).

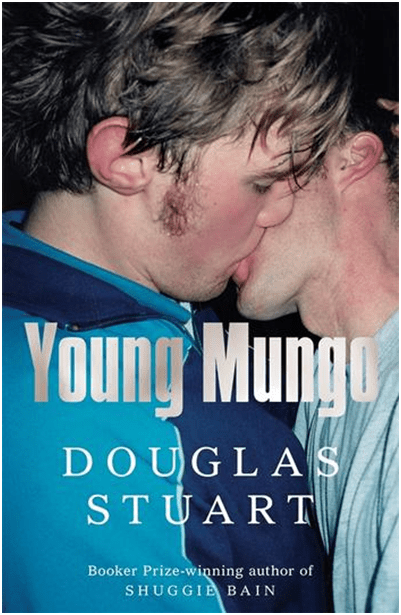

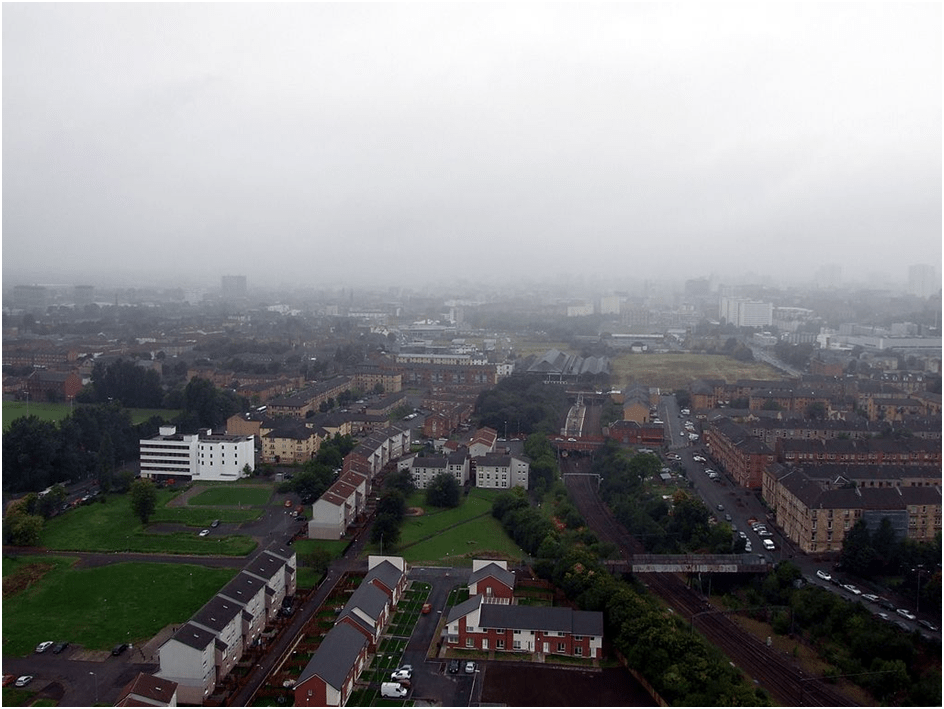

This is a novel that is continually compared to the same author’s highly successful and Booker winning debut, Shuggie Bain. This is a very great novel that my own earlier blog somewhat under-rates in pursuit of an obsession of my own about the cultural typologies that accompany third-person narration. That said, this novel follows a similar furrow (although not I believe as some reviewers would have it because the elements of character and the plot are the same) in exploiting the cultural difference between an unidentified third-person narrator and his characters. In this novel though that phenomenon in writtten form applies more generally and even to its main focus, young Mungo himself, who is a much more complex and ambivalent character, less to be merely loved, than is Shuggie. For instance, this passage talks about Mungo’s response to wild nature in a Scotland beyond Glasgow’s boundaries: a place from which he has been effectively excluded in more ways than one, for his exclusion is not a matter of physical presence in nature alone but also from the language used to describe such experiences.

A sharp wind blew across the loch…

If he had known the words to describe it, he would have said he could smell the tang of the pine forests, the bright snap of bog myrtle, vetch, and gorse, and then underneath it all, the damp musk of dark fertile soil, the cleansing rain that never ceased. But to Mungo it was green and it was brown, and it was damp and it was clean. He had no words for it. It just smelled magic.

Gallowgate was not moved by this magical wind…[2]

In this excerpt (of which only one of the three paragraphs are given in full) there are two characters whose perception of nature differ – the latter a hardened sex criminal, Gallowgate, whose name has been reduced to the area of Glasgow that bore him, and Mungo.[3] Neither could describe what the wind communicates but at least Mungo can feel its ‘magic’. That last word is not used by Gallowgate but only the authorial narrator who knows what lies within Mungo, his creation, as well as Mungo does, but who also knows ‘the words to describe it’. This is a stroke of masterly novel writing. It gives the authorial voice though an educational (and perhaps therefore acquired class) ‘superiority’. This is a supposed contrast which we see as a locus of abuse sometimes in the novel; in the person of Gillespie for instance, who uses both class advantage and his role as educational provider to sexually abuse Mungo’s sister, Jodie.[4] But if education gives a ‘superior’ advantage, it also has another function in describing the character of a boy in the process of becoming a man in a way that empathetically understands and cares for him more than he does himself, like the voice in Shuggie Bain does Shuggie.

But unlike Shuggie’s case, this voice’s empathy for its boy-hero is often contradicted by the voices of other characters who observe behaviours in him indicative of a damaged personality rather than just of a nascent and ill-understood queer identity. That queer identity will be exonerated and opened up to a reader’s love and understanding. But other behaviours signal symptoms of irreparable damage to him that are not topics of identification and empathy for the reader, such as the ‘tics’ which cause him to damage the skin on his own face. We are told of him that, ‘as the flesh twitched he began to pick at it with an index finger’. [5] It’s a trait already mentioned by Jodie, his sister earlier in the novel who tells him he had rather “just sit on your hands” than use them to ‘”pick at yourself”.[6] If Jodie is unsympathetic here, the behaviour is even more focused for us by the grotesque Gallowgate who lusts after that face and kisses it endlessly without Mungo’s consent: “Imagine. God gives ye a beautiful face. Then he does that to fuckin’ spoil it. …”.[7] In Young Mungo, the authorial voice, even when it describes a behaviour in Mungo that surprises the reader quite neutrally, exposes him to forensic analysis by other characters that unearth areas where the boy is possibly irretrievably damaged by the violence he sees and in which at times he semi-participates, in a manner that is absent in Shuggie Bain. This is particularly the case in its demonstration of how some those aspects of external violence in the world of Mungo’s family and community have penetrated within him to become a part of who he is and how he acts internally and interpersonally. We get none of this with Shuggie.

For instance in the first chapter we are introduced to the language of violence through Gallowgate’s promise to ‘fuckin’ stab’ the driver of the bus north on their fishing trip, if ‘he gies us any lip’.[8] Knives matter in Young Mungo. At one later point Mungo reluctantly accepts from his tough and hardened brother, Hamish (the leader of the local gang of Protestants) a stubby knife to use against Catholics. The early almost unnoticeable words of Gallowgate though predict its use by Mungo since he uses that same knife as a tool of unplanned revenge for his rape and battery by Gallowgate near the novel’s end. But there is another scene in which, taken by Hamish to Culzean Castle, Mungo and we are shown that Mungo has already a fund of learned but quite extreme violence ready for use, as he breaks the nose of the night watchman at the Castle to free Hamish from being caught in an act of trespass: ‘The violence sprang out of a lifetime of compacted instinct, hard-learned lessons from a sadistic brother’.[9]

This more circumspect narration makes Mungo a richer, if not more sympathetic, character than Shuggie. Indeed, I think reviews which have emphasised the similarity of the characters have read the novel too thinly and missed the fact that Mungo will take the world of Glasgow with him wherever he goes in any putative future. One such review is by Alex Preston in The Observer, who emphasises in it ‘the same basic friction: a young man growing up in grinding poverty who, because of talent, temperament and sexuality, is particularly ill-suited to the hard-edged world of the Glasgow schemes’.[10]

Mungo, I’d insist, IS not ill-suited entirely to that world, apart from the beauty of his face, which characteristic is punished by a ‘tic’ which tears at its prettiness. He is of course ill-suited to his world in quite another way, in that he falls in love with a boy who belongs to a community, that of Catholic Glasgow; a community he is trained to hate but which training signally fails. I think the distinction an important one because Shuggie too easily fits into the paradigm which makes queer sexuality only ever possible and sustainable in an embourgeoised future for the working class boy who learns of his queerness.

Everything in his world tells Mungo that his only possible future is heteronormative – the story, for instance, of Mr Calhoun, a gay man trapped in name-calling as Poor Wee Chickie, bullied by mere youngsters. But there is the story too of the ‘artistic’ boy, Gregor, told briefly by Gregor’s father in the very short piece at the very end of the novel where he gives Mungo a lift to the nearest town (I cite it in my title). Gregor’s mother tells his father predictively for queer futures (since in this case the father wants his son to stay with his family): ‘he has to go off in search of people who like the same things as him’.[11] Are working-class people then doomed to seek themselves only at a distance from where they were born both geographically and in terms of social class? In terms of the novel’s ending, the answer to this question is yes, though the resolution is wistful, wishful and self-consciously the stuff of poetic fantasy. It is an ending that is unfulfilled (indeed I suspect not able to be fulfilled). In this it contrasts with Jon Ransom’s The Whale Tattoo on which I have already blogged (available at this link), in which the queer couple at the end assemble a found family in their own locality and within its class drawn ‘limitations’. It may be no more ‘realistic’ but it is possible. For what future would the ill-educated Mungo have? Certainly not that available to Shuggie, whose education is both fuller and more useful to him and would fit him for the life of Douglas Stuart.

I have yet to work out for myself what this makes me think of this novel as a form of the modern queer novel that addresses contemporary experience. I think this important because an online blog published by the book’s publisher’s insists that the novel ‘rebuffs the idea that self-knowledge and exploration as a queer person is a journey only afforded to those wealthy enough to soar above class oppression’. Personally I do not accept that this idea has been ‘rebuffed’. The novel certainly does not show, as the blog contends, that ‘narratives of marginalised working-class queer people are not “niche”, but part of the rich tapestry of queer experience, which itself is borne out of finding, enjoying and sustaining love and lust in the most unlikely and hostile of places’. [12] For what queer love match is herein shown to be sustained or sustainable, as is the case in The Whale Tattoo.

Now, I do not argue this to denigrate the considerable achievement within fiction, including queer fiction, this novel represents. It is brilliant but as a novel of realisable working-class queer love, it barely hits any mark of note.

If it adds to the richness of queer fiction, I think it does so by refusing to resolve the issue of queer love in terms of a monolithic understanding of gay identity. I think this is vital since no such understanding could withstand the pressures of queer sexual and amative experience across highly variegated communities. Variations of working class community for instance are as yet not comprehended quite as richly by the supposedly world-wide network of queer people as we like to think. This is a symptom indeed of how this novel works, where queer identity tends to be entirely understood in terms of the kind of insult we label as ‘name-calling’. Here is one example in which Hamish (known here by his nickname ‘Ha-Ha’ – another form of name-calling in this novel that is rich and clearly consciously featured) exerts his authority, whilst his gang ransack a local business, using such a mode of insult and authority to single out a boy who speaks too often in an ‘educated’ accent:

Ha-Ha’s voice boomed over the gravel. “Haw Prince Charles! Can ah bring ye a cup o’ tea? Ya fuckin’ poofter.”

The marauders stopped what they were doing, fearful that he should be naming one of them a deviant, an aberration amongst decent men. Ha-Ha pointed his finger directly at the youth and shook his head in shame. “Stop fuckin’ wasting time like ye were choosin’ carrots to shove up yer arse.” The mousy boy scattered the toolbox as he tried to reclaim his manhood. … There was nothing more shameful than being a poofter; powerless, soft as a woman.[13]

The issue for working class communities it would seem in Stuart’s view remains not being queer per se but the fact that it renders ‘powerlessness’ and ‘softness’ visible, as it is for these boys, and many men in the novel, only in women. What the boys and men fear is the appearance of such ‘femininity’ in themselves. Yet in reality they, as men, are only powerful over women (and not always over them except in their imaginations) by virtue of physical violence (whether of developed muscle or by bearing weapons) and not in any other significant way. And thus the novel cannot resolve the issue of sustainable queer love until it ensures the sustainability of any love between two people without the threat of violence and the way in which gender power relations are exploited to enable shows of violence that otherwise change nothing in society. And when queer love is unethical it is in the same way of exerting power and violence in the image of the ‘big man’, as Gallowgate calls Mungo prior to his first attempt to rape the fifteen year old youth. At that moment, Mungo learns subservience by fully introjecting the sexual binary as a function of adult development:

Mungo didn’t want to look like a baby, so he tried a casual laugh and pretended to be in on the joke. … He felt the impression of Gallowgate’s fingers still there, still on his skin, pressing into his tender side.

Escaping this assault on his acknowledged ‘tender side’: the soft and feminised in the terms of these men, he pretends to ‘go for a piss’. From a distance however, rather than evade their gender games, he ‘was forming sentences in his mind, how to fold himself back into the group, …’ .[14] Being part of a group here involves the games played in the process of becoming a man. After all, the reason his mother sends him on a trip with two men she does not know from her Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) group (who are in fact both convicted paedophiles) is to have a ‘boy’s weekend’ that will, make ‘a man out of ye’.[15] Men continually make themselves hard out of their softest material – that boyhood which is too like the softness they imagine women to represent, whether real women do represent this function or no. Even the ‘polis’ tracking adolescent gangs threaten the boys in the gangs by saying they are ‘gonna fuck ye’ and that ‘Ye’ll like it’.[16] Being fucked may be a hard alternative but as Mungo learns, it is the one way out of becoming, as Gallowgate falsely represents his mother as saying, ‘…”a wee soft boy like the Fenian ye were messing around wi”’.[17]

Working class communities that ‘other’ the feminine, either in the naming of a ‘poofter’ or the shape of any girl or woman, is the issue the novel cannot resolve in order to make queer love possible sustainable and describable beyond acts of oppression, particularly between males, except in imagined or fictive contexts. Oppression in the book is indeed sometimes formulated literally as unwanted pressure on the skin of another. In this novel those fictive contexts are those in which Mungo and James make love for which they have no name. Once they experience such love – in touching, holding, ‘messing around’ – they play at giving the usual names for such transgression to each other like ‘poof’ (but it is half a joke in the context wherein old Scottish villages are described in a play of subtle self-reference: ‘Poof, up and gone’. “Poof?” Mungo chuckled’.)[18] They laughingly use old terms for queer identity elsewhere like ‘teapot. You big bender’ or even ‘funny-peculiar’ as distinguished from ‘funny ha-ha’.[19]

In a crucial italicised line in the novel, Mungo realises that once developing men call each other names as James does Mungo at this point (but on the basis of the religious difference indicated in the name of their respective communities) there ‘was no point’ to communication and people in such relations are ‘lost to’ each other. Name-calling after all is an attempted act of power over the other by projecting their otherness as a weapon against them:

Idiot. Weakling. Liar. Poofter. Coward. Pimp. Bigot.[20]

The status quo is, in this scene, represented by an image of a male dominating something thought to be discernibly weaker (softer that is) just as Mrs Campbell is to Mr Campbell (or in this scene a dog is to even to an old man no longer in command of a woman). Thus Jodie and Mungo as children listen to hardness asserting itself in the Campbell flat next door: ‘as he swung his fist into her softness. He was hurting her’ (my italics). [21] Whilst Mungo wishes that James could be a real man and neither love each other, their interrelation in the scene stays ‘hardened’:

There were mongrels sniffing in the doocot grass. Old men, their eyes obscured by flat caps, stood nearby and whistled gruff commands. Everything would go on as it always had.[22]

The working class are powerless in division – between Protestant and Catholic, but mainly between men and women – and will continue giving ‘gruff commands’ as a palliation for that powerlessness (or beating their wives when their football team loses). If anything, the novel feels to me, intentionally or not, to be predicating that a queer working class community is less possible to imagine because the working-class has substituted false images of power to using its united power to challenge the true source of dominion, the structures of all systematic division. I would say that is Capital. What the novel says I am not sure.

But it certainly imagines an ability to stay put in your community in the embrace not of impossible dreams but in the determined belief that one owns one’s own body rather than it being a commodity for fragmentation and use by others. For me, this is why this novel contains some of the very best writing that describes consensual polymorphous sex that is neither exploitative nor genitally focused. It lies in the moving story of how Mungo and James get to know and share each other’s bodies. The language is that of ownership, commoditisation and motivating selfish greed (as in capitalism) overturned and lived in communal sufficiency not luxury. I can’t prove Stuart intended this but look at these beautiful sentences, which turn the three-bar electric fire of the period into the most richly romantic of images:

The second time they lay together the greediness of the first fever had broken. Now there was no hurry, no selfishness. Afterwards, they lay in the glare of the three-bar fire and turned only when the heat became too much. …

Mungo held him tight. James walked his fingers across Mungo’s belly. He allowed himself a daydream as he traced his imaginary walker across the pale stomach, into the gullies of his hips and across the rise in his breastbone. …

“Imagine living somewhere quiet like this. …”.

His talk of leaving had begun to irritate Mungo. He wanted James to be here, in the now, not staring into the far distance, worried about his father’s return. … “Why would you leave? You already own all this.”

“Is it mine?”

Mungo nodded.

… “In that case, how much do you think I would get for it if I subdivided it and parcelled it off for a Barratt estate?”

“Nothing. Nobody else wants it.”

ibid: 264f.

It is all jokes isn’t it? However, it also contains the themes of whether a queer working class life is possible – the yearning to do away with the fantasy and daydream of escape predicated on belief that there can be no life for queer people in working-class home communities. Middle-class dreams are embodied in property and Barratt estates not communal council housing schemes and rooms with three-bar electric fires. It imagines a life where time isn’t itself money and hence unhurried. Mungo, untutored and uneducated yet knows that people own their own bodies, and perhaps solely these, and even these can be shared where there is mutual want and consent to each other’s want. It indicates a social dream but so does the life of individual escape from the social as proposed by capitalism.

Yet even Mungo cannot escape his learned self and it is the impossibility of such that makes us know that at the end of the novel that the ‘polis’ will not long believe Hamish’s claim that he is Mungo, and if Mungo goes anywhere, it will be that other alternative place of quest in this novel, Barlinnie prison, for murder.

Meanwhile the only ideal home of love remains a doocot, whose tiled roof has been provided by Mr Calhoun, Poor Wee Chickie, showing solidarity with young gay men locked in the same dilemmas as he had been.

Read this novel. It intrigues the more it troubles. If it doesn’t trouble you, it is still a great story, almost a thriller.

All the best

Steve

[1]Douglas Stuart (2022: 377) Young Mungo London, Picador

[2] Ibid: 148

[3] It is a matter of importance to the play with naming in this novel perhaps that the area includes the Roman Catholic secondary school, St. Mungo’s Academy.

[4] Douglas Stuart (2022) op. cit: 188ff.

[5] Ibid: 59.

[6] Ibid: 30

[7] Ibid: 60

[8] Ibid: 11

[9] Ibid: 117

[10]Alex Preston, ‘Young Mungo by Douglas Stuart review– another weepy from a writer on a roll’ in The Observer (Sun 3 Apr 2022 07.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/apr/03/young-mungo-by-douglas-stuart-review-another-weepy-from-a-writer-on-a-roll.

[11] See respectively Douglas Stuart (2022) op. cit: 334ff. & 378

[12] Available at: https://www.panmacmillan.com/blogs/literary/working-class-queer-love-stories-books-literature

[13] Douglas Stuart (2022) op. cit: 48

[14] Ibid: 62

[15] Ibid: 14

[16] Ibid: 51

[17] Ibid: 242

[18] Ibid: 266

[19] Respectively ibid: 227, 253.

[20] Ibid: 341

[21] Ibid: 162

[22] Ibid: 342

One thought on “Towards the very end of this novel a man in the Highlands above Glasgow gives the bedraggled, abused and self-alienated young Mungo Hamilton a lift in his Defender Land Rover as he treads back towards Glasgow. The man talks of one of his own four sons: ‘“Gregor’s a good lad. … Always helps his mother around the house without being asked, but he’s a wee bit …” The man paused as though he couldn’t find the correct word. “Artistic. T’cbut. Do ye know what I mean by that?”’ This is my blog review of Douglas Stuart (2022) Young Mungo London, Picador.”