LIVERPOOL 2022 VISIT no. 0: This is a blog anticipating a visit to exhibitions in Liverpool and a series of blogs on them. This one anticipates that part of it visiting the ‘RADICAL LANDSCAPES’ exhibition at Tate Liverpool on June 16th 2.00 p.m. This is a show promising art that has thought anew about a particular art genre in the context of different ways of seeing it as a social and politically charged phenomenon. Politics and the use of varied media and performative delivery of the art object itself has stretched the boundaries of the landscape and linked to other genres, beyond the simply figurative, and perhaps questioned what art is.

What does it mean to read about such an exhibition before the event? The blog tests my feelings and thoughts on that issue by reading the essays and examining illustration in Darren Pih & Laura Bruni (Eds.) (2022) Radical Landscapes: Art, Identity and Activism London, Tate Publishing.

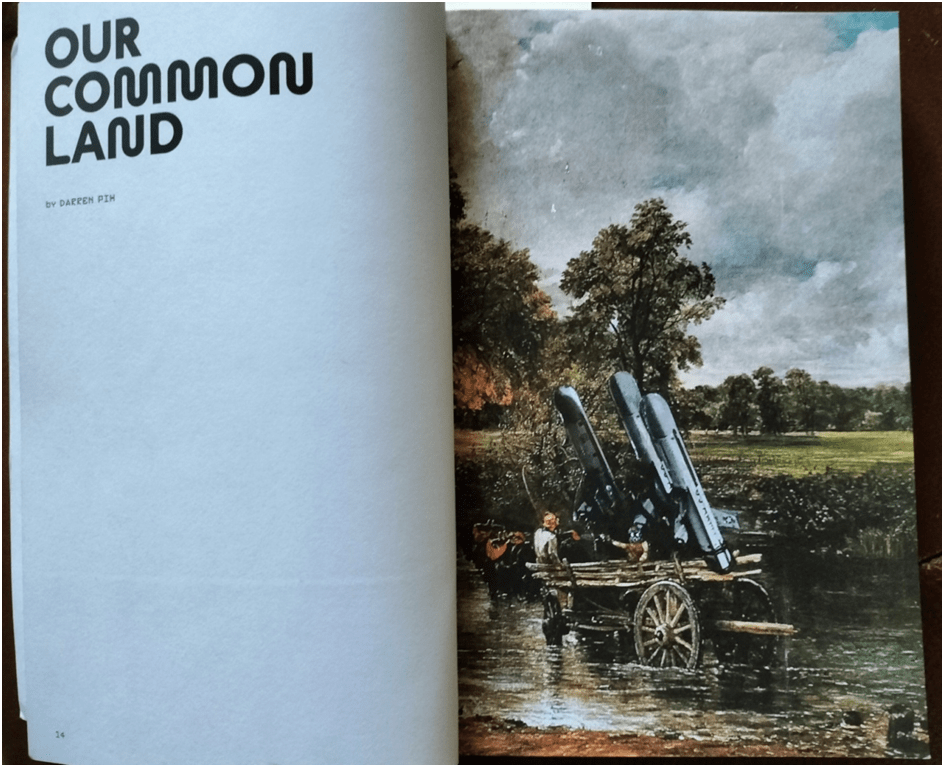

This is an anticipatory blog and I am aware that this has dangers for me, at least in relation to looking at art that uses reproduction of other (and often ‘classic’) works amongst its methodologies. The very first work encountered in the book is Peter Kennard’s deservedly well-known 1980 chromolithograph with photographs, Hay Wain with Cruise Missiles of which a reproduction of a detail is found prefatory to the first of its essays, ‘Our Common Land’ by Darren Pih.

Perhaps the first thing to be aware of is that a book is itself a medium built of reproduction, existing in numerous copies and bearing the marks of the manipulation of its contents from some source. Those sources might be in manuscript, typescript or graphic form but they must be in some sense edited and cropped in order to meet the needs of book production. The needs of book production are not in themselves simple or unitary in nature whether ranging from contingencies arising from the economics of book production or variants of the art of the book-making aimed at optimising effects of either meaning, appearance, novelty (for ‘of the making of many books there is no end’) or sequence. Note for instance the choice of the mode of introducing each essay in this sample ground with title on a bare page in an uncommon font facing an illustration from the contents (those that will be seen ‘in the flesh’ in the Liverpool exhibition), such as here the detail here from Kennard’s work focused on the major change to Constable’s iconic painting The Hay Wain of 1819, caused by the insertion (I think because I have never seen ‘the original’) of a photograph of cruise missiles poised for firing rather than transportation in some oblique trajectory. The iconic nature of this painting is a reflection of the way it has been taken as a nationalist idyll of a pastoral England, with its happy and relatively well fed inhabitants engaged in labour that never seems laborious. Examined, in another essay in the book by Goy Shrubsole, an environmental campaigner, argues that Kennard’s work is a:

fantastic piece of pastiche propaganda highlighting the absurdity of nuclear war and the incongruity of modern weapons capable of exterminating civilisation in the leafy fastness of the Home Counties. … The fact that [the hay wain itself] is bogged down in the landscape is also appropriate: the convoys bringing the cruise missiles to Greenham were tracked by protestors who lay down in front of them to hinder their progress.[1]

It is a moot point just how far we might apply the politics of campaigning to the trespass on the meanings of a painting and I find the idea of the hay wain being bogged down counter-productive myself since Constable’s point seems in the original to be how untroubling such obstacles are in pre-industrial time to the workers involved who are taking the chance of the mishap merely to pass time (an idea that is itself untrue of the rigors of eighteenth and nineteenth century agricultural labour and an ideology in itself). Transposed to environmental politics where the need is to triumph in the obstruction of those implementing their destructive war preparations, it causes several nuances too far. Surely we need to frustrate these labours and make serious the attitude of those who service a warlike status quo

However, my point is in this blog not about meaning in political art but about how reading preparation might have an effect on my expected and actual experience of the exhibition with the piece there. Art historians often lazily talk about experiencing art ‘in the flesh’ as the only meaningful apprehension of art. Here is a discussion for instance I take up with a book by a book by Martin Gayford in an earlier blog. I say of my interest in his book that:

I also choose it because of the prevalence in the history of art as a discipline, especially as a taught discipline, of over-ready uses of assumptions about the ontology of the discipline’s central objects of attention – artworks. Nowhere were these easy assumptions as clear in the assumption that the true object of study in the History of Art was art seen ‘in the flesh’, … :

“There is an odd but revealing phrase – ‘in the flesh’ – for seeing art in reality, not reproduction. … Only then can you sense the carnal reality of the people they depict, the glistening of the skin, gleam in their eyes. the weight of their bodies, the texture of their clothes. These are physical experiences, because paint is a physical substance: a layer of organic and inorganic chemicals that reflect the light, and consequently change every time the light alters. There is no substitute for being there”.[2]

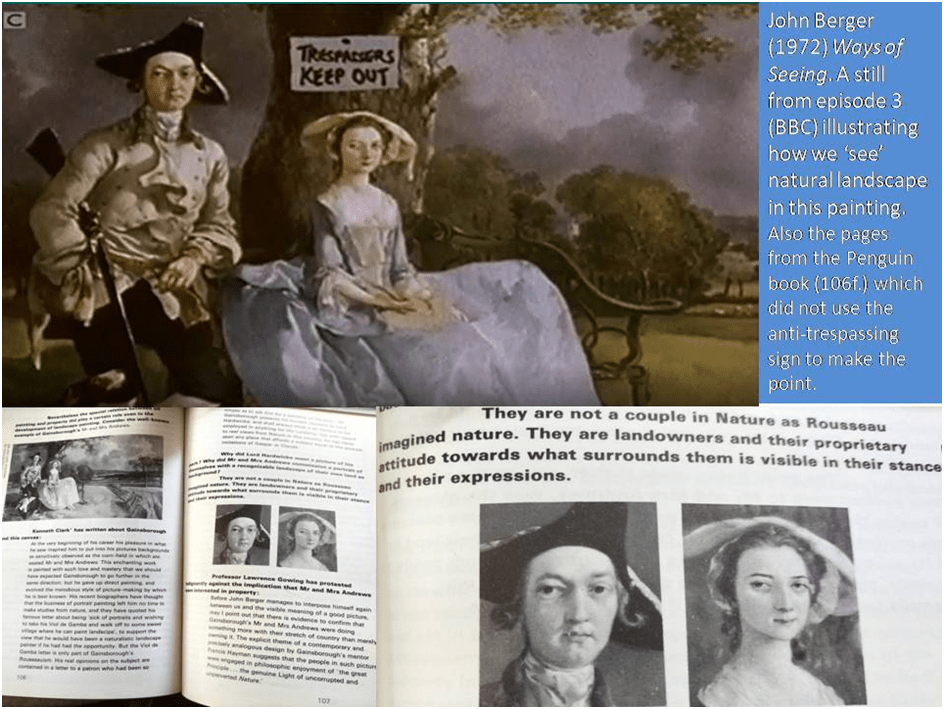

I am embarrassed by the somewhat bitchy tone of words I omit in this quotation from earlier myself which I can only explain, if not excuse, by the fact that I have never found the exclusionary tone of the history of art easy to accommodate with my working-class origins. However, I stand by the issues in relation to the phrase, for the relation of art and reproduction is itself a complex issue in a world in which commoditisation represents our chief experience of art – even in the visit to art exhibitions with the high charge they put on the knowledge and experience accumulated therein. This is indeed becoming increasingly true as well as our access to the built, and even sometimes the ‘natural’ environment. This is all the more pressing when, as this exhibition curators insist the subject of the exhibition overall is how ‘our freedom to access and enjoy this ‘green and pleasant land’ has been determined by class, race and gender’, a point they trace in terms of the history of art criticism to John Berger’s famous analysis of Gainsborough’s 1750 painting Mr and Mrs Andrews[3]. In the collage below I show not only the appropriate page from Ways of Seeing (1972), otherwise just quoted in our present book, but also the clip from the BBC series (Episode 3) which made the point about the Andrews’ ‘proprietary attitude’ to land otherwise readable only from our subjective take on issues of body language.

I use the still from Berger’s presentation of the painting on television in part to show how relevant is the attribution of ideas behind the Liverpool exhibition of that section of book and exhibition entitled ‘Trespass’. But it also makes another point about the reproduction of older art and with that some sense of the psychosocial values it embodies (such as attitude to our rights or otherwise to the land or even background context in which we are represented or at which we gaze which define ‘trespass’) does indeed ‘reproduce’ that original but does so with some added difference that challenges those psychosocial attitudes. This point can emerge easily from the reading the book accompanying the exhibition, as I have shown, and leaves open the point that Gayford’s advice to art-lovers that ‘in the flesh’ vision of an original artwork is the only access to its fundamental meanings.

Gayford is, of course, talking above about oil paintings which convey meaning not just by two-dimensional design on a surface but by the volume (apparent or real), density and texture of the coloured oil material applied – the material we call paint. Kennard’s original work is not painting but a chromolithograph which flattens the Constable painting’s design in using it for his own purpose, but it also uses photographs in some way made to adhere to the surface of the lithograph, or this is at least how I understand the description the Tate give.[4] And what I cannot see, in reading the book is how the interaction in the original Kennard between the different textures of photograph and printed lithographic colours works on how the viewer understands and feels about the work in its original form. In this sense we still need to be there ‘in the flesh’ in order to see how materials other than just paint create a sentient thought such as that of ‘carnal reality’ that Gayford attributes to ‘Lotto and other Venetian painters’. After all photographic plate and the surface created by lithographic printing on paper also have textural potential (since they too are materials) which might reflect on the meanings and feel of the work. This is precisely one effect I want to test in going to the exhibition and will report back about.

I don’t intend to spell this approach out in as much detail in what follows, although all of it attempts to refect on why, when there is a book to read and gaze at analytically as there is in this case, we will benefit at all from seeing the exhibition other than in accidental effects of the sequencing, juxtaposition and relative spacing of works, although these latter issues are important too. The only way I could imagine writing this is to look at some themes related to artistic forms and genres. A good place to start is with photography, for it is very difficult to see exactly how seeing such art reproduced in a book may differ from seeing it on a gallery wall at the Tate, although matters of texture (even the difference between matt and gloss surface) and size are obvious contenders for consideration.

The quality of the book’s reproduction of photographs is of course likely to be inferior to those set up in less popular forms of reproduction as a consequence of the quality of the materials on which, in the case of books, they are printed but this in itself isn’t of interest to me, or not (at least) before I see the exhibition. Photography cannot of course be ignored since even other art forms than it have to be photographed as part of the reproduction process in the book but this isn’t the reason why I am intrigued about the photographic art in the exhibition. In a very simplistic way we can divide the examples in the book as those which represent some scene, necessarily selectively framed of course, where our interest is in the content of a scene we are encouraged to think of as naturally occurring and captured by the photographer using the technical variations camera work enables to vary it. The examples I’ve chosen from the book are collaged below:

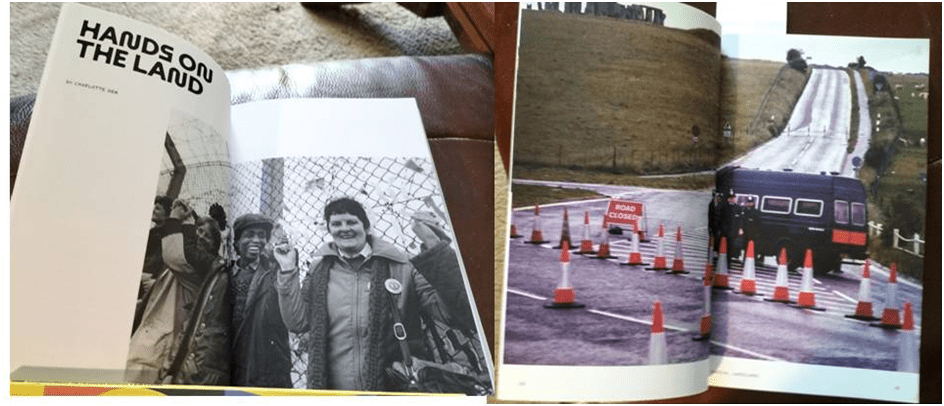

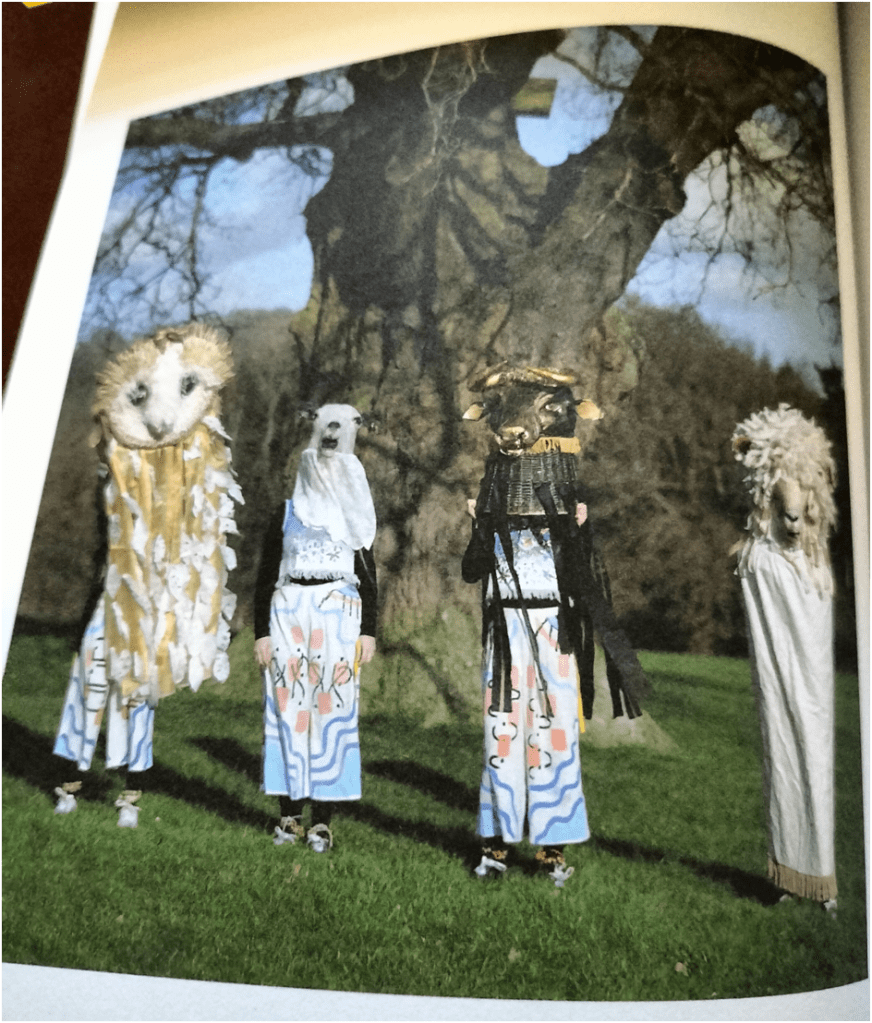

This category is art by virtue of the selection, framing and timing of the scene but otherwise claims to represent what we could consider to happen without the presence of the photographer and where events are represented, regular and formally repeated ones. I am intrigued how these will be represented as part of an exhibition and how they will be come to be seen as a radicalisation of landscape convention. Damian Le Bas Jr. argues that is because the places represented in Chris Kilip’s pictures of sea coalers are themselves self-consciously marginal to modern society and its work ethic. Where landscape ‘beauty’ is made apparent, it arises from a claims about land, literally unwanted or undesired by anyone else and filled by partial human occupation that is less than official or conventional and indeed is perhaps in part clandestine (Kilip was at first regarded as a ‘spy from the council’ investigating benefit fraud by the sea coalers). But given that this characteristic creates beautiful contrasts such as that between the child Helen’s concentration on her hula loop with the waste scattered on the ‘blighted land’ on which she plays, we might, with Kilip, sees something represented that is outside linear concepts of time and a modern drive to wage-slave economies.[5] Similarly Homer Sykes photographs are radical only in they hold constant images from past and passing ‘folk’ traditions that belong to the history of a particular place, often a remnant of behaviours out of step with current historical realities; anachronistic to normative expectations

In other pictures the scene may not be as ‘naturally occurring’ as those but which have a purpose external to their artistic record such as taking part in a mass political campaign to reclaim land more purposively that do Sykes ‘Mummers’ or Kilip’s sea coalers, such as the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in the 1985 photograph by Melanie Friend or Alan Lodge’s Police Operations at Stonehenge of June 1990.

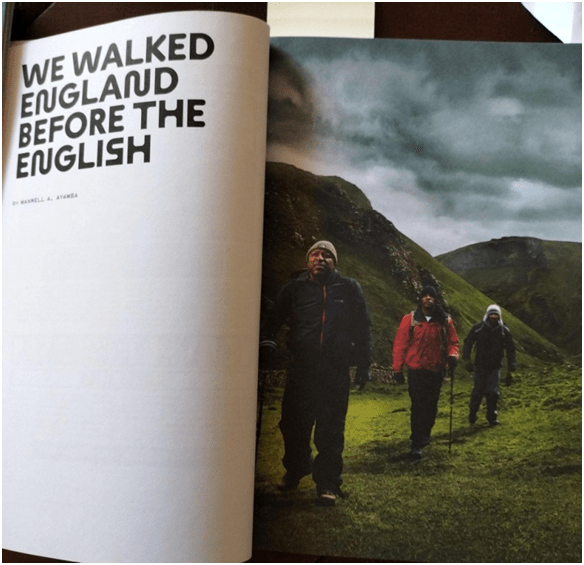

But going to an exhibition to see such photographs does not feel to me as I anticipate it to add great value to seeing them in a book, for I do not expect to see the images there in any significantly different way, but that remains to be experienced. The irritation of seeing photographs which cross the internal gutter of a page turn is of course a problem but that alone would not justify exhibition in my untutored view. Maybe here we are dealing with a claim that the photograph is not itself the art (although that cannot be true of Kilip, who is self-consciously artistic in his framings) but that that art is a by-product of human activity like the politically revolutionary or campaigning, and indeed counter-revolutionary in the case of Lodge’s picture of police attempts to reshape and de-radicalise mass political action at Newbury. That is certainly the case in terms of one exhibit in which the photograph is meant purely as a record of a more ephemeral art form such as the 2018-19 play Black Men Walking by Eclipse and Royal Exchange Productions aimed at showing that ‘although Black people may appear invisible in the British rural space they have always been part of the landscape’ in Maxwell Ayamba’s words.[6]

AS I was writing however, I felt concerned that I was writing my way out of looking forward to this exhibition. Hence, I turned then to newspaper reviews of the show. What I found has revived my interest but not because of the enthusiasm for the exhibition itself in either reviewer. Jonathan Jones for The Guardian is his usual waspish self – condemning modish radicalism with equally modish ignorant reactionary sneers aimed at all that calls itself ‘radical’. He even condemn the Tate for its ‘insulting reduction of [John Berger’s Ways of Seeing] to an intrusive soundbite’ in a looped clip – presumably the one I mention above. In the end his rather pointless review, telling us (as usual) more about his cosy antagonism to what he considers antagonist to Art (with a capital A) because he claims it hates Constable (which I doubt) and oversimplifies Tacita Dean (which I reject from evidence in the Tate book).[7] My reaction to the book, at its worst, is more like Laura Cummings’ view of PARTS of the exhibition in her Observer Review. Indeed my response to the book in its treatment of the ‘radical’ was already much like her response to these sections she is ‘confused’ by, rightly so since it is ‘muddled’ in the book too.

McCall appears in a very muddled section titled Art in a Climate Crisis. I have no idea why he is here; any more than Gustav Metzger’s five-screen Liquid Crystal Environment, which used to mesmerise the crowds at Cream concerts in the 1960s. And it is not obvious why pictures of the Scottish Burry Man, in his coat of burrs, are included at all unless you believe that he is some kind equivalent to England’s Green Man. In one photograph he is being helped to a drink in a pub. Presumably he is meant to represent the spirit of dissent.[8]

That said I can return to my own argument with something like agreement, thus far (and with the exhibition yet to be seen) that in this show the art ‘is mainly what the title suggests: social and political history by other means’. In that sense my concern about the how photography works in this show is a reflection of the muddle necessitated by an art institution like the Tate appearing to take a radical subjective position whilst being unable to rid itself of the Tate’s duty to represent a range of contemporary art of different subjective or sectional starting-points and purposes.

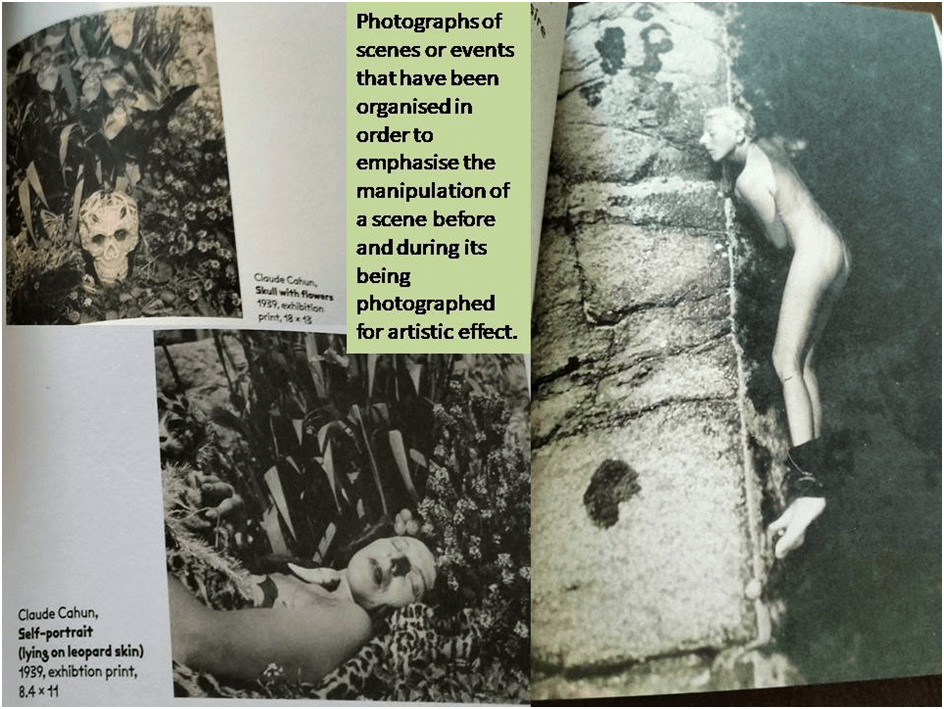

Let us take, for instance the artistic claim of the photographer as represented in the book by the photographs of Claude Cahun, who appears in her most famous photographic image on the cover of the book I am reading. Strangely enough though I have seen this piece in many art exhibitions it was the closeness of this cover image that has first allowed me to notice, under the titular claim of the extended arms (Je tends les bras) to represent those of an aged stone, the fact that Cahun allows her characteristic nose to stick out from behind the stone which hides her body and feature as a kind of reshaping of the stone’s already irregular and worn anciently carved margins. Is this saying something about the extended exposure a book image allows over that available even in the most lightly attended exhibition.

Hence if we use Cahun’s work as represented in the exhibition book to represent the artistic photograph in which the subject of the photograph is itself ordered and organised with artifice, we see that the concern for contrasts of line form (curved, angular or straight with irregularity or none) and surface textures (of hairless skin, water, stone, foliage and flower) are all designed not only to convey ideas but imagined haptic sensation that may not require an ‘in the flesh’ apprehension of it. We shall see.

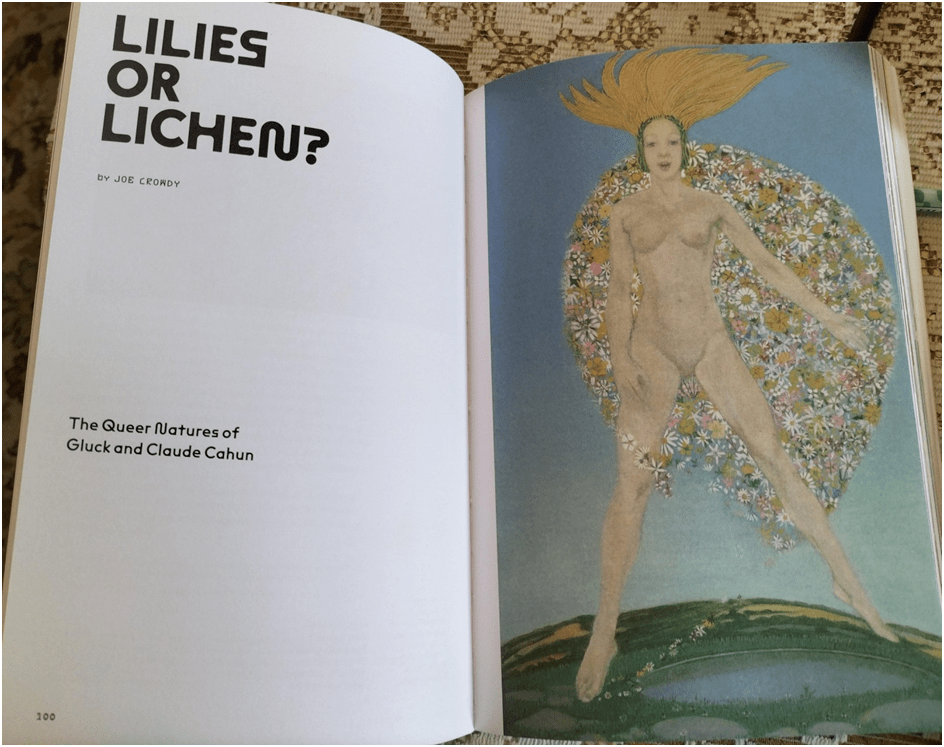

Another sign of possible muddle in such an exhibition (again we’ll see) is the difficulty of treating an artist like Cahun in terms of subjective positions determined by identity such that we abstract from her intrinsic cleverness and ability to query norms of perception of what is natural and what manufactured a ‘queer identity’ akin to that of Gluck. The comparisons between the two queer artists aren’t made very clear except that Cahun’s view is a ‘more irreverent, eccentric idea’ but both are interpreted by Joe Crowdy as representing ‘a new, joyful queer nature’.[9]

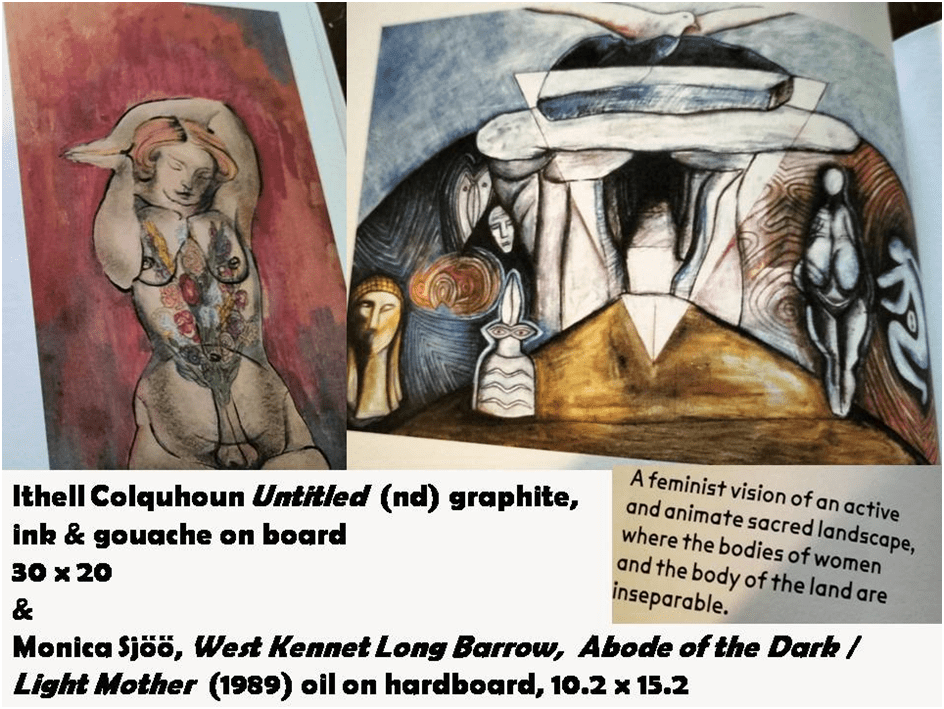

In the final self-analysis I wonder whether my antagonism to all this is because the political is defused in a new pantheism, which seems to be the exhibition’s (if the book predicts rightly) take on the dominant view of feminism it argues, with a stress on symbols (sometimes just floral as in Gluck) that are archetypal in an almost Jungian manner. Take these examples:

They are tremendously interesting. Indeed the Colquhoun gouache appears to suppose the fertility of the woman in a fleeting appearance of the hermaphrodite, and is thus a form of queering of the binary divisions of sex / gender, although it references the pagan archetype of Flora, but the Sjöö painting is all paganism and primitive archetype in a kind of modernist translation that is tremendously clever but fails to excite me at all. Strangely enough this is the element, read as an extension of Blake’s world-apocalyptic and quasi-political symbolism that Jonathan Jones thinks the show would have profited from being more like:

…: joyous, life-enhancing and therefore truly radical. It could have juxtaposed William Blake’s depictions of the ancient bardic British land with Deller and brought in masses of weird old folk art to show us the hidden popular story of the land. But no. Even when acid house is pumping out, this exhibition can barely let its hair down before exploring some other reason to be cheerless. Blake is represented only by a sneering text that disdainfully refers to this “green and pleasant land”. You’ll never build Jerusalem in a place you hate.[10]

That might indeed have been a means of making the exhibition feel consistent and less muddled for all takers but would, in my view, have dated it back to some of the worst forms of politics in the 1970s-80s; the hopelessness of pressing a flower into the palm of power and pretending that this equalised the participants in the political game, without recourse to radical changes in the systemic ways in which oppression operates to marginalise – even sometimes the culture of ‘the many’ – in the interests of a ‘few’. In truth my expectation is that Laura Cummings will be proved right about the show in two ways.

First that the show will prove ‘just a little too tame to be properly radical’. Second that it will be straining the point that she makes that it is of the nature of art proper and in itself, from Byzantium to David Hockney (but why stop there) ‘that makes the landscape seem strange’.[11]

This is true in exhibits I expect to enjoy in the flesh in seeing classic oil landscapes, even those of Constable, who is made to appear a ‘victim’ of the shows rhetoric by both reviewers. But, you know what, Constable WILL survive the rhetoric and even the destruction of some of the patriarchal and normatively-conservative values his painting definitely support in our current art institutions. And then of course there are those painters for whom the phrase an ‘ESTRANGED LANDSCAPE’ seems written like that produced of Northern England by the fabulous Edward Burra. The book (and indeed the review by Cummings) promises me one such; a favourite:

The secret of the queerness of Burra’s late landscapes goes deeper than is conveyed by calling them radical, although as representations they are. They force us to evaluate the interaction of the built, manipulate and ‘natural’ in landscape so that we never use the word ‘natural’ as if it were a simple term to understand ever again. There is so much to see and say and feel about this painting that I will say nothing and just sigh at its pain and beauty. That is as far perhaps as art, even performative art can go unless it breaks the barriers and boundaries of what our society currently calls art in such a way as to challenge laws that preserve the status quo’s oppressions. I think Alan Lodge’s ‘art’ may do just that and I hope the show is able to demonstrate that, as the book of the show cannot quite do so.

Much as I admire the pluck of the Mummery and folk pastiche of what I have learned from the exhibition’s book about the group of Jonathan Cherry’s photographs of Boss Morris (and the part played therein by Jeremy Deller) and I’ll await the show to eventually decide whether my prejudices will be maintained, about whether it is any sense ‘radical’ or, for me, even palatable – for I cannot imagine WHAT exactly is going to be exhibited.

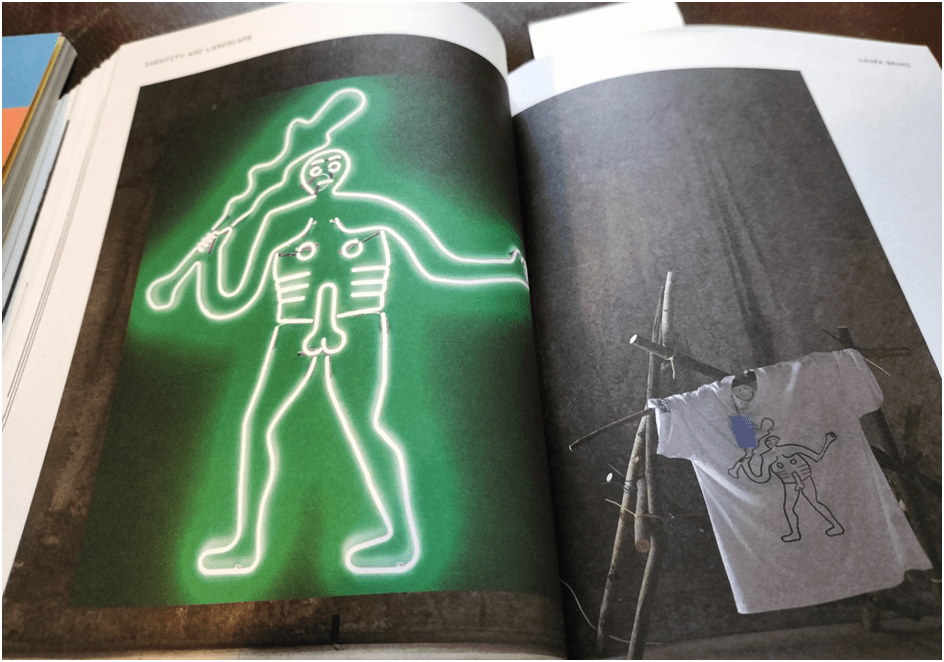

Meanwhile I am excited to anticipate seeing Deller’s 2019 work in transforming ancient (perhaps because its ancient origins are contested) land art such as the Cerne Abbas’ giant.

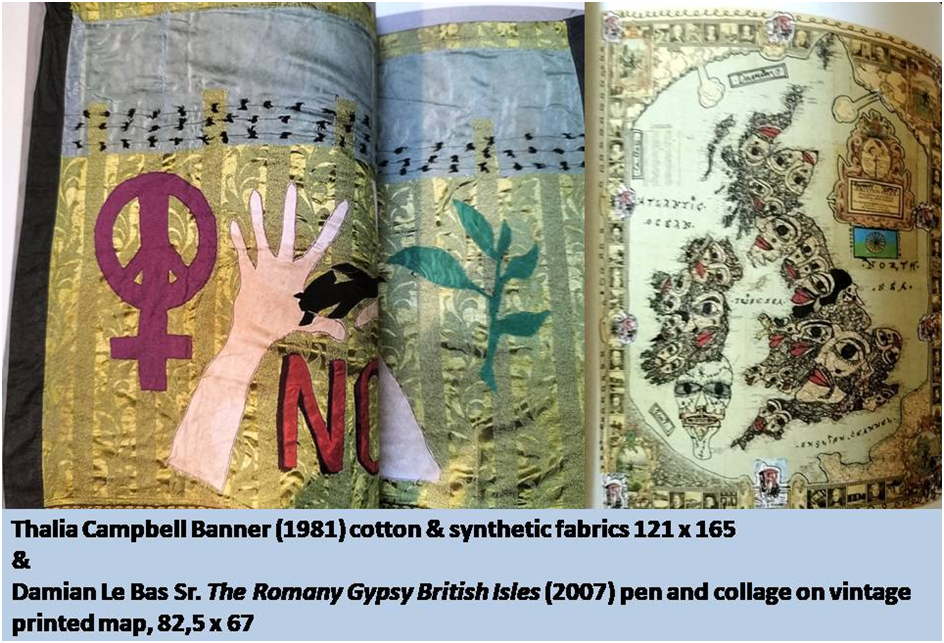

I also believe that sometimes we might not notice that banner art is purposively political. It shouts messages in contexts which make it part of trespass against the barriers created by law around unequally possessed land, at Greenham, Stonehenge or any part of the ‘native land’ of the UK in which some races actually invited to live there are not allowed to equally own as a ‘native right’, because they are black (I am looking forward to seeing Sonia Boyce’s work) or travellers. A banner might even wrap a body bloodied by oppression and still be innately itself but its symbolic value matters because it is part of a struggle. For travellers that symbolism when in a map form is also political because it points to the resistance to the notion of ‘settled’ rather than nomadic communities, and all the sequelae of that distinction.

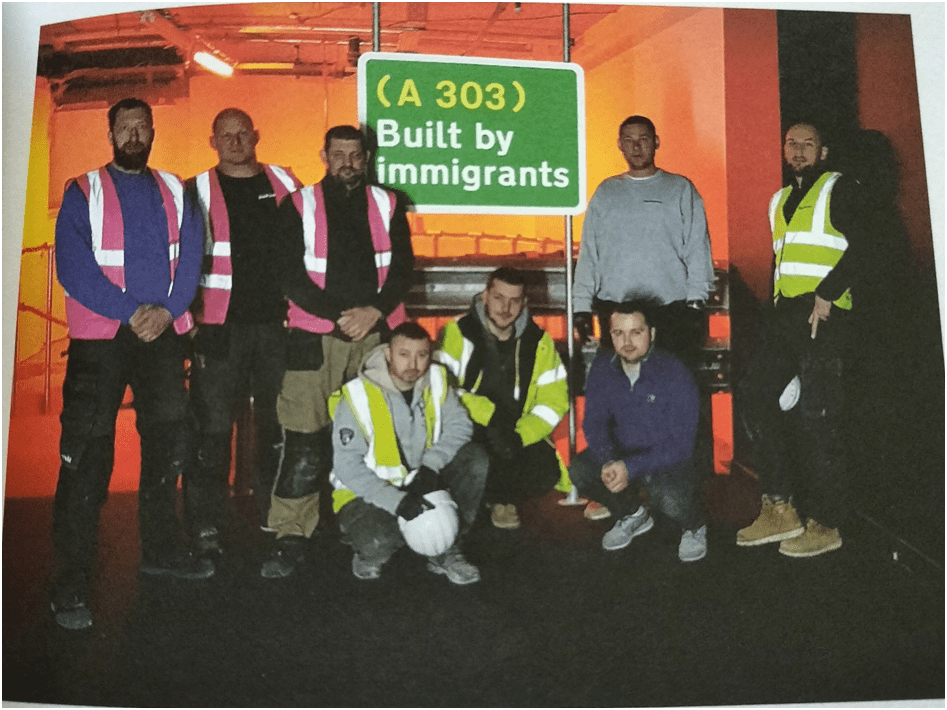

The same may be said of road signs as politically sensitive when the information suppressed from them is restored, as in this work I am keen to see – in terms of WHAT exactly will be represented (surely not just a photograph). The sign itself would be powerful.

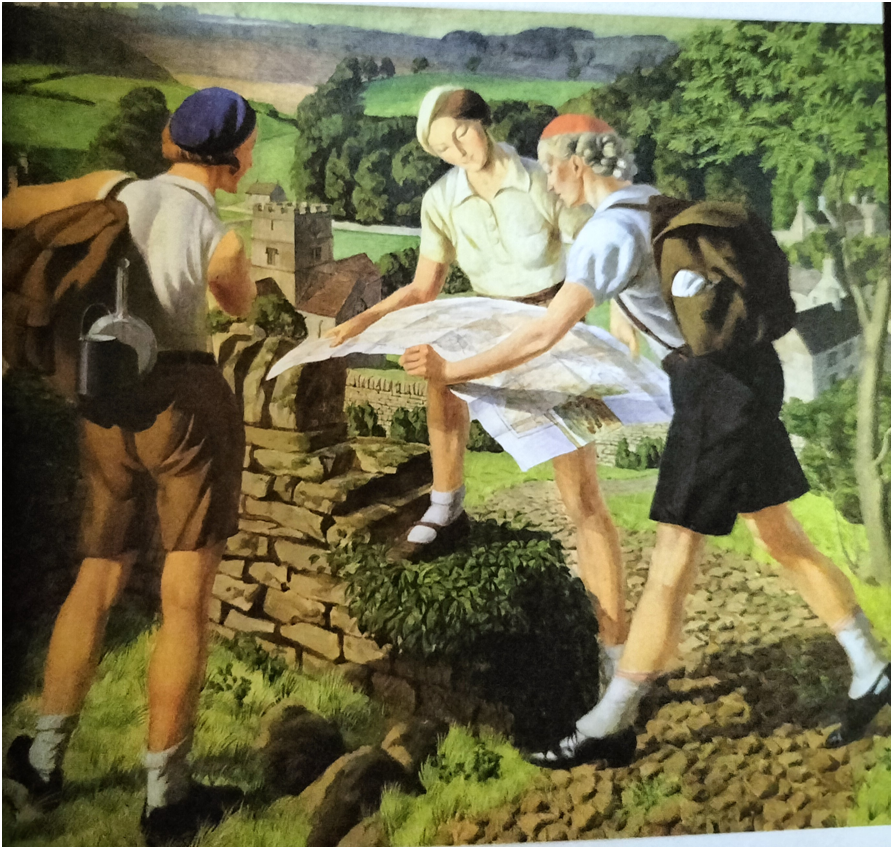

I think one thing I hope the exhibition is able to communicate is that all public representations serve to estrange us from at least some beliefs about the ‘natural’ or indeed the ‘native’ and that is true of art that is good art but innately racist, as I would not myself say Constable was (since his art reflected values that were not consciously being promoted, even if they need to be exposed). But consider this fine example of poster art from the exhibition which self-consciously whitens the occupation (in both senses) of the nation and natural. It is self-conscious because it is aiming at a rural myth that excludes black people who were absent for reasons the poster will not explore. Healthy athletic white human flesh is the promoted aim here, such as I have explored before in a blog on British Art Deco.

The landscape here is as estranged as that in Edward Burra’s view of Northumberland but estranged in a way its audience would find comforting with its central view of a church and cosy homes dominating the landscape in the gentle background and the remoteness of the higher mountains. This is landscape estranged as tame with nothing of the wild, not even such that might scuff the young women’s attractive and fashionable patent leather shoes. How they became so fit (if determinedly NOT in a masculine way) is impossible to fathom. But in ideology why do we need to fathom it.

At this very moment I am looking forward very much to seeing this exhibition and will report back when I do.

All the best

Steve

[1] Darren Pih & Laura Bruni (Eds.) (2022: 26f.) Radical Landscapes: Art, Identity and Activism London, Tate Publishing, 24 – 35

[2] My blog available in full at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2021/05/06/there-is-an-odd-but-revealing-phrase-in-the-flesh-for-seeing-art-in-reality-not-reproduction-1-what-do-we-pursue-in-the/ The quotation in second paragraph is from: Martin Gayford’s (2019: 181) The Pursuit of Art London, Thames & Hudson.

[3] Darren Pih & Laura Bruni (Eds.) (2022: 16, 19 respectively)

[4] ‘chromolithograph on paper and photographs on paper, 26 x 37.5’ ibid: 27

[5] Ibid: 54 – 57

[6] Ibid: 38[7]Jonathan Jones (2022) ‘Radical Landscapes review – ‘Is loving green fields really wicked?’ [Fri 6 May 2022 08.00 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/may/06/radical-landscapes-loving-green-fields-wicked-tate-liverpool-tacita-dean-constable

[8] Laura Cumming (2022) Radical Landscapes review – consciousness-raising from the ground up [Sun 15 May 2022 13.00 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/may/15/radical-landscapes-tate-liverpoool-review

[9] Ibid: 103, 102.

[10] Jonathan Jones op.cit.

[11] Laura Cummings op.cit.

One thought on “LIVERPOOL 2022 VISIT no. 0: This is a blog anticipating a visit to exhibitions in Liverpool on June 14 – 17th and a series of blogs on them. What does it mean to read about such an exhibition before the event? The blog tests my feelings and thoughts on that issue by reading the essays and examining illustration in Darren Pih & Laura Bruni (Eds.) (2022) ‘Radical Landscapes: Art, Identity and Activism’.”