Joe Gunner, the hero of The Whale Tattoo, recounting sexual encounters with Jim Fysh, a long-term boyfriend who has entered a heterosexual marriage, says: ‘…, I listen to him talk about how right it feels and I tell him, “these things you want can’t ever be right.”’ This is a blog on a new kind of bald and ‘dirty’ fiction about working-class male queer relationships (where even the ‘clouds hang like dirty curtains’) that considers the rights and wrongs of achieving ‘the in-between place … Where there’s no noise and nothing matters’.[1] This is a blog on Jon Ransom (2022) The Whale Tattoo London, Muswell Press.

This book has not been as widely reviewed as it should and where it is, it is mainly in the queer press, perhaps because this novel is sold from the publisher Muswell Press’ LGBTQ+ list. Moreover, at its heart is an exploration of a teen romance and its adult sequelae between its narrator, Joe Gunner, and his lover and sexual partner, Tim Fysh. However, where the novel was picked up in the mainstream astute reviewers have recognised its power as a work. In one case James Smart uses the tiny space allotted to him by The Guardian to suggest in relatively few words how portentous the writing is in this novel. I think I’d like to quote the first and a little of the second paragraph (it’s a large part of the review for there are only six paragraphs in it in total).

Joe’s Norfolk town might be an idyllic place. Marshes stretch to the sea, eels wriggle up creeks and oystercatchers stalk the mudflats. Here “mirrored pools … burst with sky”, and the tide “comes and goes, like one huge breath”, transforming water into land and land into water.

Yet Ransom’s powerful debut is as bucolic as a fish hook through the cheek. Fishermen scrape a living near rusted tankers and burnt-out cars, the water below them “the same filthy grey” as the sky above. Feelings are bottled up and families strain with violence and resentment. Almost everything is old, battered or rotten. Prosperity and progress feel a long way away; …[2]

I rather like that this reviewer opens his review with reference to terms usually applied to a refined genres that has straddled the history of literary forms; notably the idyllic and bucolic settings and themes which touch upon the pastoral genre of writing. No doubt this is mainly so to stress in the second paragraph that this is an anti-pastoral piece, which renders a darker side of a rural and unpopulated (perhaps more strictly depopulated) scene and its economy. But even this piece suggests another deeper level of the fictive which this story touches that is not entirely at home with the realities of lives pinched by an economy not designed primarily to serve them but for them, as consumers and producers, to service it. The people I refer to above are those people we see inhabiting desiccated lonely landscapes, though once lived upon by a more prosperous past community, trying to work in a dying industries like fishing or taking part-time work in a fish-and-chip shop.

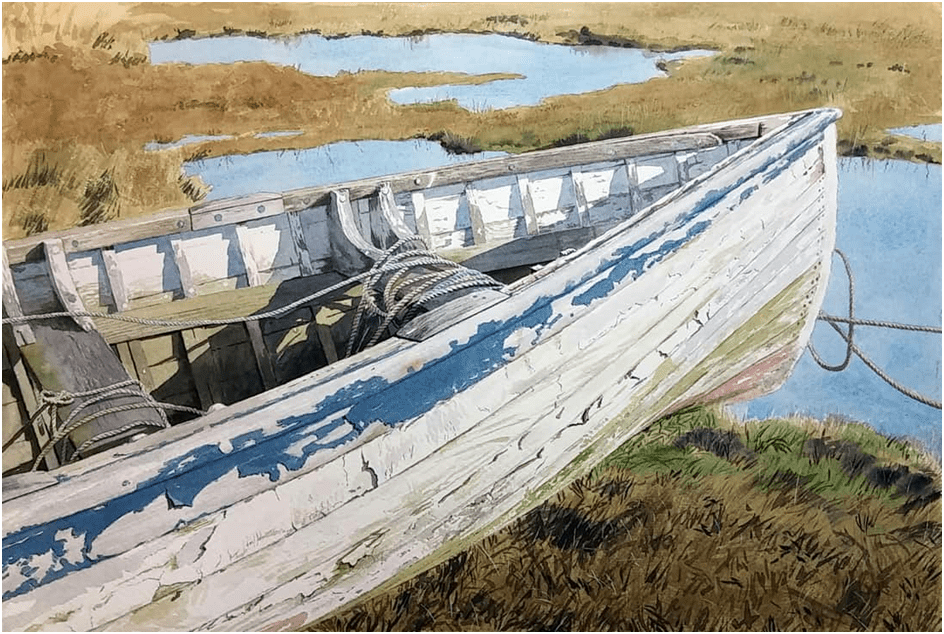

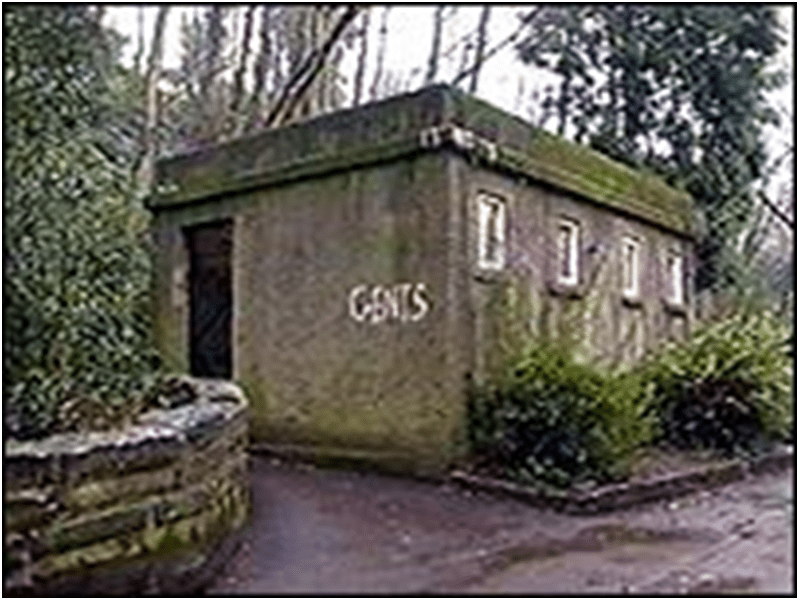

They live with the ‘wrecks’ of boats and buildings; signals of the decay of both industries and public wealth, that once created a network of civic amenities like public toilets. While abandoned and wrecked boats or ones in the process of that loss of function stagnate through this novel, being places where encounters, including sexual encounters, occur, public urinals are also seen as symbolic of the general flow of waste and, since the novel never covers up visceral bodily realities in its language, ‘shit’. The latter too become available trysting places for the novel’s lovers who require invisibility to escape homophobic hatred.

However, that ‘deeper level of the fictive’ in the novel, as I have phrased it, and which some reviewers call its poetic language are part and parcel of natural or post-human landscapes and processes of decay and natural reclamation that continually demonstrates magical transformations. Smart may or may not have pointed to that in citing, as he does in the paragraph from The Guardian review I quote above: ‘Here “mirrored pools … burst with sky”, and the tide “comes and goes, like one huge breath”, transforming water into land and land into water.

I do not know if I have any deeper appreciation of this fictive level but it strikes me as the ‘stuff of which dreams are made of’ and of magical fantasy. In a sense this will serve an ethical purpose in the novel: one that focuses on redeeming human character from the stereotypes of the purely good and evil. For instance Doug Fysh is Tim’s heterosexual brother and the most deeply unpleasant of the novel’s characters. But central to the dénouement of the novel and Joe’s moral awakening is that he is not as ‘evil’ in the end as the novel throughout leads us to expect him to be, just mind-numbingly selfish and mind numbed by that trait. Fantastic stories bear straightforward battles of good and evil, the agencies of light against the horrors in the dark night but moral life is not like that. After George Eliot novels may have stopped telling us this so clearly but Ransom is, to my mind, in her tradition of writing about our shared social life, even though he takes it into the realm of working-class lives that has been darkly lit, if lit at all, by literature.

When I sensed the poetic in the novel (before reading any of the reviews I mention) it was in being struck by the sense of networks of certain colours even discovered in the incongruous everyday business of the novel, kaleidoscopically mixed sometimes like the multi-coloured clothing put into a washing machine that pervade and run through the novel and knit together its incongruous parts or single striking colours, like purple, that run into the sink from the purple flowers tended to at that sink by Tim’s widow.[3] Let’s stay with (to coin a phrase) ‘the colour purple’. Purple is the colour of Doug Fysh’s t-shirt,[4] for instance, but not there elegiac and domestic as in the purple flowers with which Dora Fysh rebuilds the look of her husband’s male lover’s family home. But it also ‘marks’ the landscape: ‘Purple water cuts an unholy line through landscape’.[5] At another point we are told that at ‘around this time’ every year, the grass will ‘turn a surprising shade of purple’.[6] In the opening of the final chapter of the novel the colour sets the time of a winter scene: ‘Snow on the ground is coloured purple in the first light’.[7] And then, of course there is the ink of tattoos or the blood through skin that produces dark near purple birthmarks, which is, after all what the whale tattoo is: ‘the mark on my face … / … used to be nothing much more than a stain. But it’s turning darker, looking like a tattoo. Fysh said he could taste the sea when he licked me there’.[8] And Fysh’s face is purple when it is bruised during the theft of his bike to Joe and his sister, Birdee, it also marks the troubled agitation of his wish to have sex with Joe.[9]

A veritable tangle of colour plays through this novel almost like a symphonic mirroring between its sections; often played though let it be noted against a stream of near excremental brown like the ‘threatening brown muddy tongue yipping’ of a working river flowing through mud played its own discordant cacophony. Other elements however than colour emphasise magical transformation in the novel’s narrative and symbolism, such as the transformational effect of the tides cited by Smart above. Tides take objects from the world but also return them, acting almost as if an agent of loss but also of redemption as they do with the teal suitcase with which Joe and Birdee’s mother was going to escape her violent husband except that the ‘tide doesn’t want it either’.[10] But it is the tide that also refuses to take Joes’ body in suicide and returns it to the care of a soldier who once loved his sister.

If this is death, I will be alright. Not so terrible. Beneath bruised darkness, light is forgotten here. … No tide taking me where it pleases. Rough palms on my chest and stomach tell that the wet hasn’t followed me to the after-place. … “You’re safe,” he says. “I’ve got you”. The Soldier. He yanked me from the river. Yanked me back from the in-between. … / … Why’d you just let me drown? ? “Don’t be stupid. Besides, the river didn’t want you. Tide turned you over to me”.[11]

The play between life and death, wet and dry and light and dark here plays a double role, which somewhat creates the liminal space we might call an ‘after-place’ if we are religious or ‘the in-between’, a twilight world so common in this novel where antinomies coalesce in some fashion as in magical fantasy. The word for such places is the liminal and this novel embraces the liminal in every which way, ending with an almost textbook version of a chosen family in which time and space boundaries are redrawn to facilitate non-normative and shifting and otherwise variable identities across time and space negotiated over water.

This is at the heart of the fact that this is an intersectional as well as queer novel for it flies between lots of social categories and binaries and I will return to this theme of the ‘in-between’ or liminal places in the novel later in this discussion But at this point I want to show how the magical liminal (and ‘poetic’) potential of this novel is a means of introducing a subjective perspective that made room for the emotions which tend to get almost embodied, as it were, in natural processes and landscape turned into the realm of some almost supernatural power, which I have already hinted that Smart refers to in his Guardian review . If we return to the use of tides for instance see the effect of talking about them in Joe’s memory of Fysh as a way of understanding how his sister’s affection might have been won by Doug Fysh, the ‘twat in a purple t-shirt’. The metaphor here turns Fysh into a kind of minor Prospero in command, if not of tempests on the sea but, like Cnut in the imagination of others, tides on a tidal river: ‘Fysh could conjure the tide to turn if he wanted. And I’m wondering, maybe Doug could too-‘.[12]

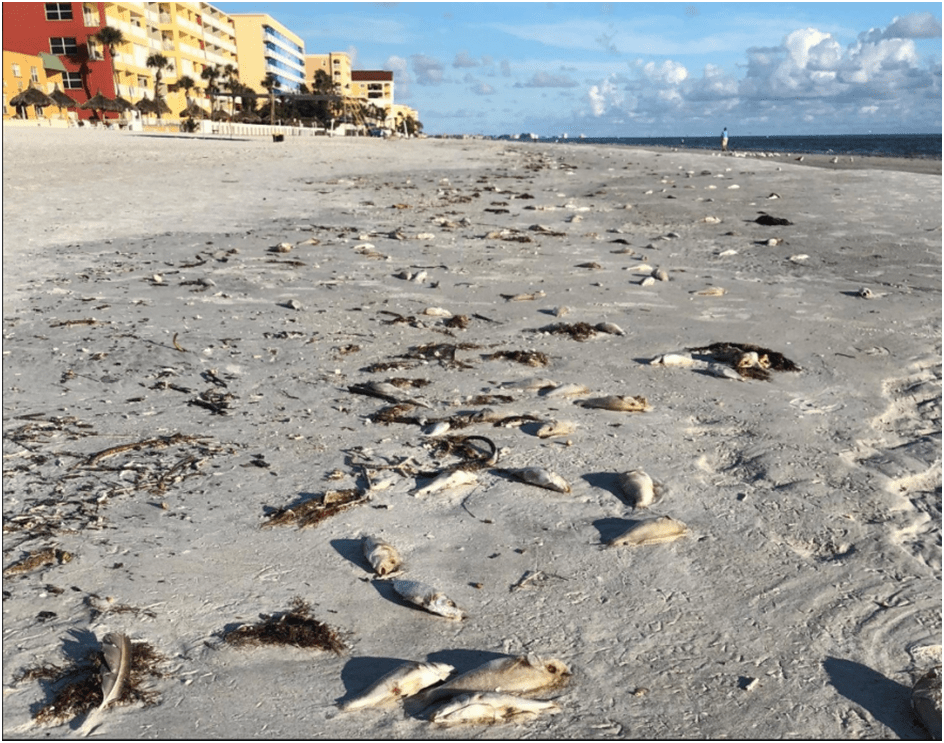

Those natural landscapes and processes are ones of death and life, such as the central haunting image of the whale dying on the beach on which it was grounded but they are in main represented by the river which ‘speaks’ to Joe throughout the novel. Like a recurring motif in an opera it ‘speaks’ to Joe like an interior register of that which he refuses publicity such as seeking relief in sex with substitutes for Fish such as Fat Lad and Hold-your-Horses but also thoughts of suicide or destructive vengeance.[13] Eventually, its purpose done in that it has eventually forced recognition of one of the events that has led Joe to think that ‘death chases him’, the actual drowning of his sister, ‘The river is quiet –‘. As he says later to Dora that ‘threatening brown muddy tongue yipping’ has ‘stopped talking’.[14] Whilst the river is, in a sense, an obvious projection of the repressed content of Joes’ thoughts and feelings, its purpose is also to show that attempts to distinguish depth and surface in one’s mind are without purpose because both connote one fact – self-hatred connected to both how one looks on the surface we show to others and how one feels and thinks about self and one’s needs at a deeper level. It is all a ‘slur’ (an insult, a smudge or a stain or all three): ‘I will burn the river dry, before I leave this place behind. Call what slurs beneath up to the shiny surface, and not squander my chance to wreck it’.[15]

Below the surface is not only a whale but a ‘pike’ associated to suicidal thoughts themselves as it dies struggling ‘like it’s having a fit’. He remembers taking the pike from his father’s catch from a coal-black lake as a child which will be left to rot in a dark box just as its he remembers its sequel – his rescue from suicide (his first attempt) by his father: ‘That’s when i consider what’s beneath the surface. Hiding. I jump into blackness. Liquid coal chases me. It’s quiet here. Until it’s not’.[16] It’s not – because he is rescued, brought back to the disturbance of living surface noise that reminds him he is waste and wasted mortality. Later under that surface is Fysh and the sex he wants but he thinks might not be ‘right’ because hidden and pleasure taken at a cost to others, such as the pregnant Dora, Fysh’s wife. But in the box with the pike, we will find, is the torn half of a photograph of Tim and Doug Fysh, of which he has kept only Tim Fysh’s half.[17]

That is recalled in the suicide attempt itself:

I want to be with Fysh. Maybe he’ll be beneath the surface. Waiting for me. …fuck her. Fuck all of them. He’s waiting for me. Currents quickening, tugging at the top of my legs. … Tingling, like Fysh is down there busy with his tongue. Fingers finding the surface, feeling the swell. Moving up. Moving down. …

That prose is liminal between up and down, surfaces and depths of different qualities, life and death – an ‘in-between place’, but based on alienation and aggression to all others, a kind of amorality that, in practice has no future because it is constantly hidden and must continue thus in perpetuity, associated with darkness, smudge and slime, even though sometimes like flies on excrement as Dora says, that has its beauty when ‘the last light thrown off the winding water smudges the marshland until everything shines’. Notice here again how the smudge (or ‘slur’) takes on beauty though it must wait for the last light. This is the sex of the public toilet or in isolated wrecked fishing boats, which leaves a taste in like the ‘boak’ (or vomit since both words are used) in people’s sickened mouths as in this picture of failed sex in a public toilet with ‘Hold-Your-Horses’:

I am relieved the mirrors are broken. The reflection thrown back belongs to neither of us alone. .. The five terrible stalls, doors ajar, are riddled with graffiti. Do you spit. Or do you swallow. There’s a filthy urinal running the length.[18]

But let’s not forget the balance in this novel that refuses to allow ubiquitous ideas associated rightly or wrongly with dirtiness and filth cannot also be beautiful, for the liminal might be beautiful in its ugliness. It is to the ‘in-between place I go’ that sex with Fysh takes Joe, for neither have a word for love.[19] In fact Jon Ransom writes of this wordlessness in working-class boys denied a queer culture in a piece he wrote for The Literary Sofa. For absence of cultural validity is what the marginalised are left with in a divided society like ours.

Emotionally these lads might seem incapable of articulating their desires. But this isn’t true. They just can’t speak them. Instead, they perform small acts of tenderness where their actions give up what hides beneath social constraints and inherited masculinity. The most Fysh can do is push his knee against Joe’s beneath the tabletop while necking a pint in their local pub. But with this small act of tenderness Joe understands everything at once; that if he was a girl it would be the same as holding hands. That Fysh is saying ‘I love you.’ Their affection for one another is quiet, but not misunderstood.[20]

Ransom rightly stresses the class elements which lead to the exclusion of working class boys from the languages of queer, if not heteronormative, love as well as cultural heteronormativity for his vision is truly intersectional, looking at the dynamics of both powerlessness and power between the criss-cross continua of identities related to gender, class, disability and status.[21]It does not produce a sense of the marginalised however as ‘victims’, although oppression is clearly shown, but as of distinct subjective potential previously ignored in the culture. This is very much to my taste.

For instance, take this moment where Joe realises the power of his male gender vis-a.vis the women who necessarily come into his life, here Dora here visiting with him a speedway bike stadium, Tim Fysh’s widow and who, we shall see has been sexually used by Doug Fysh in the shadow of his bisexual brother’s relationship to her.

People looking might think she’s mine. That the baby inside her belly got there on a night not unlike this one. Air ruined with fuel, fucking her upright in the car park. And they’d be right in part. For I did fuck Dora. Just not how a lad is supposed to.[22]

Over the page from this the ambiguities of the verb used here are made much clearer, for in patriarchal heteronormative society if we are male we all contribute to the humiliation of women: ‘“Who’ll want me – dead husband – baby – I’m fucked”. It will take the moral commitment to refashion gender relations to change this, an intention that if we all contribute to ‘fuck’ women’s lives, we need to ensure that we care to ensure their independence and dignity after the event and this is how the novel ends. A review, in the queer press who do not feel the need to define terms known well to the LGBTQI+ movement speaks of the novels ending with the ‘theme of unexpected ‘found family’ and self-acceptance’. But as I will explore later this is because our novel reinvents the novel of moral decision-making.

However, I want to make the idea of the novel’s ‘intersectionality’ clearer or hope to do so by taking it into an area more concrete in relation to the novel’s queer themes. For there is a great self-consciousness in this novel about how male characters who have sex with men define themselves, which has little to do with some kind of essentialist notion of ‘gay identity’. The words ‘poofter’ and ‘queer’ are used regularly and are used not just to show a pejorative association coming from people identified as homophobic such as Joe’s father,[23] but it can be used that way, but often, as Doug uses it below, whilst on a shipping expedition with Fysh, who has momentarily gone away, and Joe to distinguish a man who can and perhaps does have sex with women as well as men from men who only have sex with men. Doug breaks the news to Joe that Dora is pregnant;

… Shakes his head. “He needs to be a husband – father.”

If Doug has a point, i wish to hell he’d make it before we both drown. Or worse.

“He ain’t thinking about his wife and baby while he’s fucking you.”

“Huh.”

“You’re a poofter. A fucking little queer.”

… / “My brother ain’t like you.”[24]

Joe even uses the term ‘poofter’ to speak of himself because his behaviour with Fysh is not only sexual, of which all men are capable, but demonstrably and visibly affectionate; ‘…, I slide off Fysh and lie alongside him. … I lean across and kiss him on the cheek. Fysh. / “I’m sorry,” I say, because I’m acting like a fucking poofter’.[25] The irony is of course that as he begins to identify his connection as emotional, Fysh has become a dead body, choked on his own ‘boak’ in his sleep.

This novel raises for queer readers the words we use to identify ourselves and the rationale for the use of these terms. In fact the rationale slips constantly between different usages – negative and pejorative or definitive of a behaviour but is never defining really of self. Why should it be? For amongst the men who have sex with men in the novel, including fit Lad and Hold-Your-Horses the reasons for their participation barely define anything. And some men act in ways that might in other circumstances define amative or sexual behaviour or both without embracing any definition at all, thus is the Soldier who loved Birdee and seems wordlessly similarly attracted to Joe because he looks like her, without either of them becoming visibly sexually interested in each other. Read this piece of their interaction, as their mutual showering and bathing without evoking wordless nuance:

“Joe,” he says, his hand on my shoulder turning me around.

Now I’m against his chest. He’s hugging me tightly. While I cry. Big heaving sobs that frighten the crap out of me, worried that I’ll never be able to stop again[26].

Even more ethically innovative as a character is Peter, with whom Joe finds by the end, a loving relationship that is not defined by the sex it includes and can be an open partnership, setting up a chosen family with fluid boundaries compromising different genders, social statuses, and forms of loving association. The relationship with Doug is a truly ‘in-between place’ but realised in this world not in imagination, even though the dead partake of it as well as the living:

The sofa is too small for the two of us, squashed up somewhere between fucking and his clever book. Uneasiness is stalking me again. I should read behind my head and put out the light. Dim to dark. Until at the edges it’s so black I’m not certain I’m even awake. In this in-between place they appear at their brightest. … My dead are watching me.[27]

The Soldier is morally complex. An apparently caring man, his motives are for revenge against Doug Fysh, for the assisted death, as he guesses it to be, of his beloved Birdee . And in the end, he is perhaps the double of Doug. It is appropriate then, as double stories go, that each becomes the nemesis of the other leading to Doug’s death (but not as the Soldier had planned it) in a bar and the latter’s imprisonment. His plan for Doug’s death fails because Joe refuses to be part of it and listens to Doug’s explanations as The Soldier does not. This is the moral nub of the book and reveals that Joe has taken on board that Fysh’s use of him and Dora is perhaps not so morally correct a relationship as he might hope. As he refuses to allow Doug’s assassination by the Soldier he thinks of Fysh again as that amoral Prospero: ‘his eye’s’d be shiny, hypnotising, conjuring something I’ve never had a name for’. The conclusion he makes is about what is right and what is wrong and based on recognition of morality as a phenomenon in its own right: ‘All the wrong ruining us’.[28] Fysh near the end of the novel is remembered in an amoral light that Joe distinguishes from his own developing ethical grasp: ‘Teasing with his hard-on. I can hear him, clear as glass. Telling me I’m wrong to believe there’s things he wants that’ll never be right. Fysh didn’t care about rules’.[29]

These moments of moral dénouement are completions of a pattern that opened in Joe questioning himself and Fysh whether it was also morally right because it was pleasurably so and evoked a world of liminal uncertainty to engage in secretive sex with a man who had chosen to seek a life defined by wife and baby, at least if the woman involved, Dora, had been left to fend for herself and was in the dark. Let us quote it again: ‘…, I listen to him talk about how right it feels and I tell him, “these things you want can’t ever be right.”’ And in the end, like Jane Austen and George Eliot, this novel asserts that there is no ‘in-between place’ where ‘there’s no noise and nothing matters’.[30]

Please read this book. It is something exciting and new that still evokes great traditions in the novel, of importance to us all, identifying as queer or nay. Its progenitors are the books Ransom cites in his interview, including the wonderful Garth Greenwell, for the NATIONAL Centre for Writing of people on the same quest who are brave enough to find that in queer fiction as in George Eliot there is still space where ‘everything matters’ and we must learn to love and respect each other in actions as well as words and ‘identity’ is secondary to that.

All the best

Steve

[1] All quotation in title variously from Jon Ransom (2022: 3) The Whale Tattoo London, Muswell Press

[2] James Smart (2022) ‘A Powerful New Voice of Working Class Gay Life’ in The Guardian (online) [Wed 23 Mar 2022 11.00 GMT] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/mar/23/the-whale-tattoo-by-jon-ransom-review-a-powerful-new-voice-of-gay-working-class-life

[3] Jon Ransom op.cit:15f. (for the kaleidoscope of colours), 181f (for the purple flowers and the sink)

[4] He is the ‘twat in a purple t-shirt’ ibid: 194

[5] Ibid: 109

[6] Ibid: 119

[7] Ibid: 225

[8] Ibid: 196f.

[9] Ibid: 41f.

[10] Ibid: 15

[11] Ibid: 187f.

[12] Jon Ransom op.cit: 181

[13] See for instance for that recurring motif Ibid: 11f., 27f., 45f., 55f., 83f., 99f., 117, 139.

[14] Ibid: 157

[15] Ibid: 85

[16] Ibid: 34

[17] See ibid: 35, 132 for details

[18] Ibid: 81 9italics in original).

[19] Ibid: 3

[20] Ransom has also stressed his own origin as working-class Norwich, attributing his successful debut with this novel to an Escalator programme which put budding and inexperienced writers in the care of published writers, for him this was Anjali Joseph, whose background could have not been more educated and middle class. Yet this spoke to Ransom’s ability to learn from this encounter how to overcome an inability to gauge the value of his writing to a literate audience, large, of course, also middle class. He says something like that in a case-study interview for the National Centre for Writing: ‘Our discussions help me believe that what I’m writing has value. Outside of a programme like Escalator, especially coming from a working-class background, it’s hard to measure your progress in any real way’ In Isabel Costello (ed.) (2022) ‘Guest Author – Jon Ransom on Three Unspoken Words’ (the words are ‘I Love You’) in The Literary Sofa. [Feb 2nd 2022] Available at: https://literarysofa.com/2022/02/02/guest-author-jon-ransom-on-three-unspoken-words/

[21] National Centre For Writing (2022) ‘Author case study: Jon Ransom’ [3rd Sept. 2019] Available at: https://nationalcentreforwriting.org.uk/article/case-study-jon-ransom/

[22] Jon Ransom op.cit: 169

[23] Ibid: 133

[24] Ibid: 24

[25] Ibid: 58

[26] Ibid: 191

[27] Ibid: 228

[28] Ibid: 209

[29] Ibid: 191

[30] ibid: 3

3 thoughts on “‘…, I listen to him talk about how right it feels and I tell him, “these things you want can’t ever be right.”’ This is a blog on a new kind of bald and ‘dirty’ fiction about working-class male queer relationships (where even the ‘clouds hang like dirty curtains’) that considers the rights and wrongs of achieving ‘the in-between place … Where there’s no noise and nothing matters’. This is a blog on Jon Ransom (2022) ‘The Whale Tattoo’”