This blog reflects on Terence Davies’ Benediction based on seeing it for the first time on 20th May 2022 at the Roxy Screen, Tyneside Cinema, Newcastle.

This is a film about the wastage of young male lives but not solely in war. The latter is early predicated in the loss of Siegfried’s brother Hamo (Thom Ashley). For the film is finely balanced between the pathos and tragedy of the death of young men, the corpses of whom clutter French mud in the black and white original footage from the war at the film’s opening, and the lament of old queer men (and sometimes very unhappily heterosexually married queer men) at its end for the abandonment of their youth. The division matches the balance between Sassoon’s brilliantly played (by Jack Lowden) youthful ambivalence and the sour character of the older Sassoon, also played so brilliantly by Peter Capaldi (so brilliantly that people will begin to dislike him).

The sourness was already implicit in the youthful ambivalence as Lowden shows Sassoon floating between the hubristic and sparkling self-display of an Oxbridge intellectual and those multiple moments in which he finds the only meaning in his life in another. Expressing his belief that his son will be the sole purpose and meaning of his life to that baby, his new wife, Hester (Kate Phillips), reminds him he once said that to her. There is something beautiful in how both the naivety and absolute belief of those pairings is convincingly shown in the film, as witnessed the moment of meeting (well before betrothal but predictive of that) Hester Gatty in a dance. In the end the souring of the relationship with both the older Hester (Gemma Jones) and his son are searing, though the latter is somewhat mitigated. The older Sassoon compares sourly too the lack of weight given to him even by the literary world compared to T.S. Eliot – though he must have realised Eliot’s greater momentum as a poet.

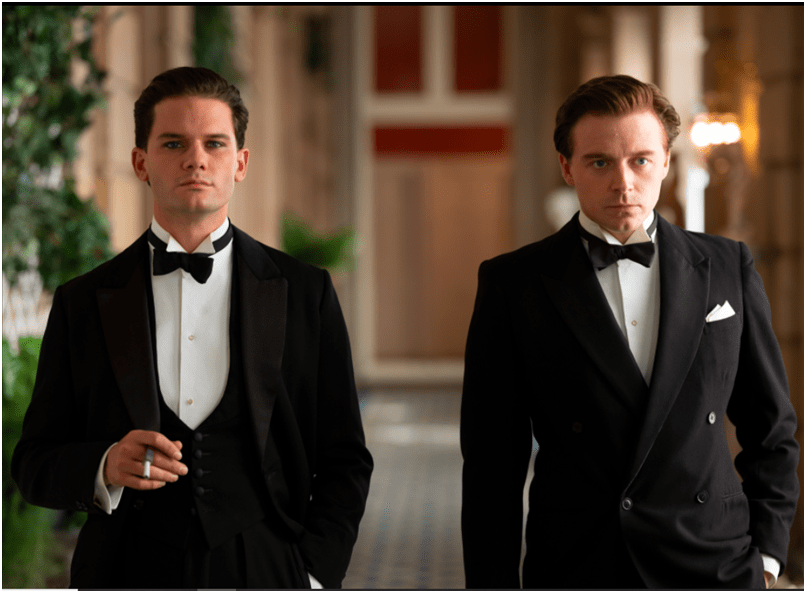

Naive trysting is replicated in various moments elsewhere with male lovers ranging from Wilfred Owen (Matthew Tennyson), Glen Byam Shaw (Tom Blyth) and Stephen Tennant (Calam Lynch). There is only sparkle one might feel in the moment in the yet still naive moment where Sassoon and Wilfred Owen are imagined pairing at Glenlockhart War Trauma Hospital under the almost queer parental care of Freudian psychiatrist, W. H. Rivers (Ben Daniels is the man to a T).

For me the most memorable glory of this film is a scene in which the pair rehearses ballroom dancing (with Owen taking the role usually danced by a woman) under the disdainful gaze of the Chief Medical Officer (played with the glee that comes with playing military homophobic monstrosity by Julian Sands). But Owens death in 1918 is only the first of the losses of love suffered, though the means is more varied once the war ends but that often involves a fashionable ennui with a lover by now too well-known and stale.

For the lightness of loving in these communities as we too often imagine it (and thus belittle it in my view) is also conveyed, although it never taints Owen (unsurprisingly since he dies before it can) and Sassoon – who continues bitterly to hate the ‘unfaithful’ Stephen Tennant (Anton Lesser as the older man) until the end, when even Hester welcomes the latter back. There is no doubt that no-one (queer or nay) will like the character of Ivor Novello as played here so brilliantly and cattily played by Jeremy Irvine, such that his perpetual smirk – had it been true of the original – should be enough to warn off lovers tinged with either seriousness (like the real actor Glen Byam Shaw) or jealousy (like Siegfried Sassoon).

The true nastiness of Novello (as this film portrays him fairly or unfairly) is captured in the imagined disdain throughout the film with which he treats Robbie Ross, the one genuine picture of a fulfilled older queer man – W. H. Rivers is portrayed in middle age only. Ross is played with the ubiquitous charm and panache you always find in Simon Russell Beale. As Novello has to be reminded, Ross had stood by dear old Oscar (Wilde) and illustrated that beneath wit something more substantial like the love that can exist between men in whatever relationship.

This is however not a film in which women emerge with any fullness of character at all – though that is the issue with script and direction rather than acting – except as in monstrous parodies of socialites like Ottoline Morrell (Suzanne Bertish) and (best of all) Edith Sitwell (Lia Williams). They show us comic acting at its finest. The latter performance I could watch and laugh with even if repeated over and over again.

In the end the message of the film is that queer lives were as tragically curtailed as the lives of young men in the war, but that isn’t quite good enough a take on how real queer people negotiated those years I think. This may be because the film is intent on shoving in as many gay young things as possible – so much so that I pity the good actors playing Rex Whistler and T.E. Lawrence. Were they not there to show off the brilliance of the scene without enough meat in their roles, in this film, to allow them to be registered in their full worth as actors [or as the men whose part they play so beautifully]. For the loss of life in war is not on the same register of experience as the undoubtedly terrible wastage of lives, love and desire amongst young queer men. That is not the kind of easy moral paradigm for instance you find in Pat Barker’s Regeneration Trilogy or others of her novels, where queer lives are not emblematic only but made to live again.

But this is a wondrously beautiful film and I will watch it again (and again!). Don’t miss it. Not least don’t miss it because of the art that is made from its technical brilliance – where slowness of delivery is never dull and where the collage of different media and voiceovers that read poetry are as wonderful and beautiful of the drama tragic and comic you will also find. There are excellent performances here – like a master-class of British acting.

All the best

Steve