Writing of his confrontation with literary periodicals and ‘avant-garde novels’ in the autobiographical account of his youth entitled Emblems of Conduct, Donald Windham says that whereas commonly people focus on ‘morality based on security’, ‘security seemed to me the limiting of possibility, and a morality based on security to be immoral’.[1] This blog considers how the work of Donald Windham creates a stance on ethics and morality that, in the 1960s in the USA and Western Europe, embraces the world of endless queer potential and the risk it involves. It reflects on reading the Donald Windham’s literary story-telling (with the assistance of other writings) and focused on The Warm Country (1960) set of short stories, The Hero Continues (1960) and Two People (1966) in the first UK editions of each published in London by Rupert Hart-Davis (the first two titles) and Michael Joseph Ltd.

Donald Windham was a young queer man from Southern USA (born and raised near Atlanta) who left the South for New York with his first male lover, risking taking on an entirely new identity from that into which he was socialised. This is the story told in the autobiography of his youth and published in 1963, Emblems of Conduct. Much of the queer content is, of course, rather implicit but can be inferred from the choices the hero of this autobiography eventually makes, and (for those in the cultural know) its dedication to his life-partner, Sandy Campbell, and the use of an epigram from W.H. Auden. Some of the implications are a kind of knowing parody of the choices a queer young man must make inevitably as he grows up. He might go along (barely even choosing that life because it seems all there is on offer) with living (or ‘enacting’) the conventional life-story expected of him by family and facilitated by the visible and easily accessed social networks of local conventional life. On the other hand he might actively choose something different: some variation in the appearance or dynamics of one’s way of living caused by choosing in a way that is not conventionally pre-scribed. Another way of saying this is they chose a life that had, for most young queer men at least, no socially validated script.

Emblems of Conduct emphasises this difference of choice by a constant contrast between the first person narrator of Windham’s autobiography and those other persons that, rather than chose a life of their own creation, instead, at least in part, ‘fit into’ the world of middle class work and leisure. The latter lifestyle flows from not challenging the conventions of two pillars of the status quo: those of salaried work and forms of leisure ‘paid for’ by that comforting and regular income of money. It is a world of ‘security’ in that it appears unchallengeable. Now, in this novel, it is clear that the cyclical nature of capitalist economies never really provides ‘security’ and that the two symbols of security in such economies, (‘money’ income and a ‘home) are ever fully secured by capitalism. Hence the real importance in his life and writing of the Great Depression of the 1920s in the USA. That idea is finely communicated in Donald’s childish dreams about his ‘house’: ‘… a house that is empty… a house that someone is trying to break into. The rooms are bare … Around each corner lies the unknown’.[2]

A further element of the ideology of security in economies of ownership, other than ‘home’ and ‘income’ is that of a nuclear family and this too is precarious in the reality of Donald’s early life. His father’s wild dreams of affluence go sour and his mother struggles to raise her children after divorce from that man of dreams. Yet this image of security in family remains unchallenged – until it is finally rejected by Donald leaving home for a less secure life in New York, just as, perhaps, his father did. For ideology is sustained by the representation of everyday life as a kind of theatre in which the script and roles constantly make pretence that not only the processes central to capitalist economies but heterosexual marriage and the nuclear family are stable and enduring constancies. Indeed this idea of the stability of the status quo under capitalism is a necessary ideology of the system. Fictive stereotypes of stable and secure identity serving the status quo have a heavy cost in fact: ‘the price of playing its representation of myself’. Indeed Windham more fully describes, a short time before this quotation, an even clearer articulation of the fictive and theatrical nature of the scripted and limited lives that must be enacted or ‘played’. In a description of the golf-club party hosted for employees and their families (‘husbands and wives’ and mothers and their marriageable sons being the ‘natural’ population of those categories) by the Local Coca-Cola Company Club the narrator says that in that event: ‘There is not as much variety as there might seem. Everyone plays the conventional representation of himself’.[3] The only exceptions are the outcasts with their transgressive desire for more than convention provides. They include his father, who to a rebellious child takes on the form of the romantic hero challenging the conventions they have failed to enact as they should. In this way Donald’s father becomes for him the ‘exact shade of my own longing and belief’ for escape from convention and limitation.[4] The latter includes, of course, the heteronormative dream of heterosexual marriage.

The autobiography and Donald’s youth finish with the subversion of both heteronormative and gender expectations alike in the reproduction of the real writer’s sexual partnership with Fred Melton under his avatar in this novel, the appropriately named Butch, Butch’s touch releases the most extraordinary metaphor of sensual release that might occur in everyday life, because the unscripted has been chosen in preference to convention that might have met a need for security but rendered his life dull and immoral, in its lack of integrity.

…, in the vagrant closeness of the moving bus, I feel the anonymity of New York … placing you in the middle of the extreme possibilities of yourself and making you choose which you will move toward.

I can smell the rum on Butch’s neck. My hand touches his arm. Clusters of neon, fading in the country night, like socks running in a basin of water, forecast Manhattan’s sky.[5]

It is a blunt instrument of a metaphor that of the dye running from a sock but it jams home in my view the sense of the fantastic emerging from a new domesticity, the homely in the vagrant intruding on a new experience at every move of this ‘wanderer bereft of possessions’. It is, in short, a new kind of ethic based on taking chances that might lead to poverty and loss of status and life, everything rejected by the rigid ideological conventions of Atlanta, Georgia.[6] And here it is linked to the queer tension experienced of the smell and touch of Butch by Donald. This tense grasp of the ethical choices offered in life also has an impact on writing too. The writing itself takes risks in the interests of representing a changed world like that seen through the dark and rain, even in Atlanta: ‘Even in the dark this visible change must occur. … (I)n the whole neighbourhood, the whole world that I know, everything must change as it is changing now’.[7] The role of metaphor is like rain to defamiliarize that which we thought we knew: render the known as the unknown but strangely still familiar (or ‘uncanny’) in Freud’s definition of das unheimliche.

Fleeing to New York in a queer relationship, although the queerness lies more in the style of writing than details of their life, is a way of making an ethical decision in line with personal truths rather than choose the ‘security’ of the conventional with its access to money, alienated labour (in the Coca-Cola factory) and a heterosexual marriage of convenience because it challenges no-one. This is why I chose my epigram in which, ‘security seemed to me the limiting of possibility, and a morality based on security to be immoral’.[8] The former is the choice of Donald’s brother, who was more ‘concerned with security, and morality than Mother’, but not of Donald. It is a tale then about becoming like his father thinking he is escaping convention but of someone interpreting ‘moral choice’ and its nature anew in which he can be queered: become ‘a different person and – for practical purposes, according to the standards of the people around me – totally amoral’.[9] Note that he is only amoral to conventional standards. After all, the purpose of this biography is to create new ‘emblems of conduct’.

Windham also dealt with this period of a boy’s growing up in his first novel The Dog Days by choosing a protagonist very unlike himself – one from the USA underclass created by the Depression and queered by notions of being a ‘misfit’ from the offset. His character is captured in networks of reference to psychotic experience, criminality and other kinds of otherness. I have written about this in my first blog on this writer (accessible from this link). Yet the hero of The Dog Days ends not in being free of a life that is conventional, for he never had that, but in suicide, thus mirroring his beloved Whitey. For suicide is the image of removal from a conventional world so oppressive it kills off any queerness or otherness that might trouble it.

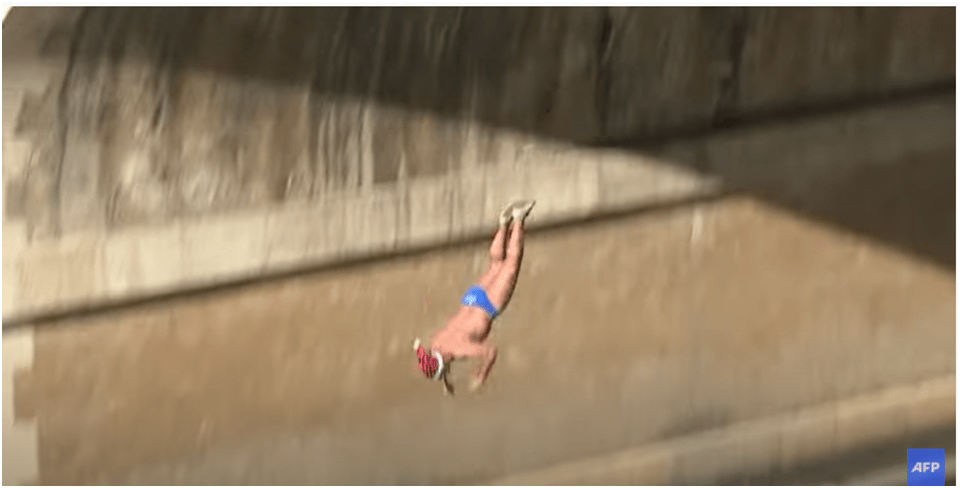

In passing it’s worth noticing that the very first line of Windham’s best novel (in my opinion) two people, where a communal adventure engaged in by young men as part of New Year celebrations is initially apprehended by Forrest as a story of the mass suicide of young men. It is a newspaper story of youths who jump from bridges into the Tiber river, a story some distance from the behaviour conventionally expected of young men by Forrest, the American narrator, but totally acceptable to Romans:

A number of people jumped from bridges into the Tiber yesterday. …

Their intention, it turned out, was diversion, not suicide. … jumping into the Tiber is a Roman way of celebrating the New Year.[10]

Again this novel tells of a man making life changes that appear to him a kind of risk (as is diving into a cold river in January) that might constitute social suicide for a man from a conventional American bourgeois family.

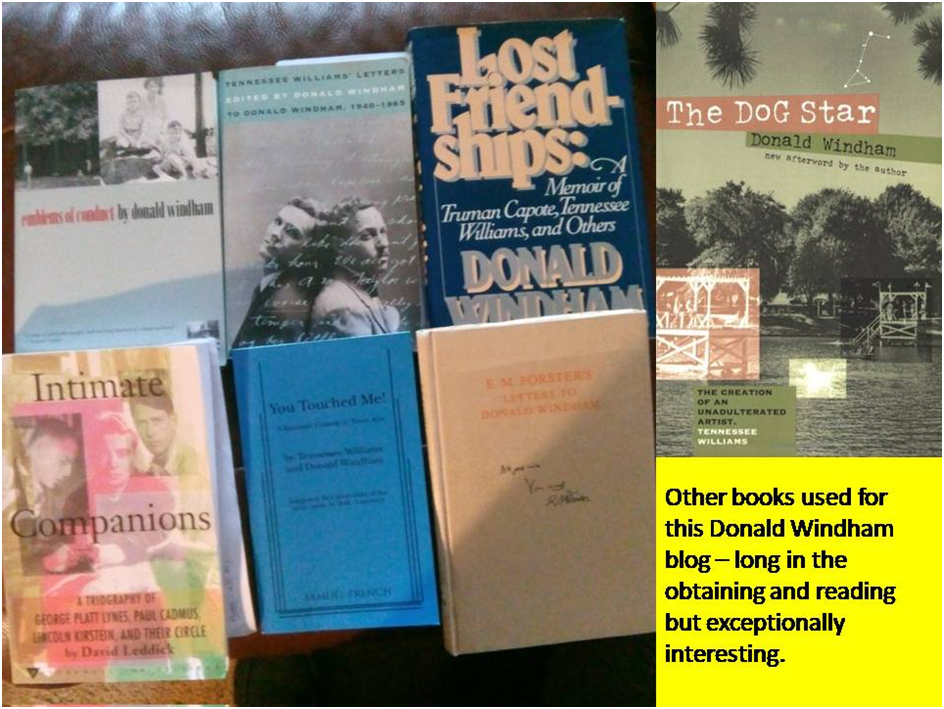

It would be premature however to consider the novel two people in full now for two other very considerable works preceded it in terms of date of publication. Let’s start with his short stories anthologised under the name of its most significant story, in E.M Forster’s view but also humbly my own, The Warm Country. In my first blog on Windham I cite the introduction of this collection in a caption to a photograph, which I will repeat again here as a self-citation.

In the Introduction Forster wrote for Windham’s published short story collection The Warm Country, Forster says he came across the writer’s short stories first in 1947. He praises the American writer most for his belief in ‘warmth’, writing about human beings containing ‘flesh and blood’: ‘he believes that creatures so constituted must contact one another or they will decay’. Ultimately without contact, the human race freezes to death in the dark’. [11]

Forster is a master of the simple and repetitive metaphor used as a means of setting up paradigms for the expression of the unspoken in his own novels. His empathy with extended writerly play of a metaphor of felt heat or its absence in Windham is liked By Forster I’d guess precisely because it is a metaphor of this nature. Hence, it would be a mistake to think the great writer merely simplifies Windham’s use of the paradigm here. The purpose of his description in this introduction is to show, with some precision despite appearances, that Windham’s stories necessitate belief in the value of taking risks with the securities implied by ‘cold’ convention to avoid the ‘decay’ of visceral humanity. In Windham’s play, co-authored with Tennessee Williams, and based on D.H. Lawrence’s short story The Fox, You Touched Me, warmth, sensuality and love outside legitimated middle-class conventions are all cognate with mutual touch between human bodies, as spoken by the illegitimate orphan, Hadrian, to his step-mother, Emmie, and which she classes as the ‘usual class resentment of persons in your situation’. Hadrian expresses a wish to touch the breast of his mother, to Emmie’s disgust. But this breast is in fact a symbol of what he describes thus: “Something warm … To be warmed – touched – loved! … that longing, not satisfied yet. To be touched’.[12]

This is recalled in the short story ‘Servants with Torches’ where Sergio feels the hand of a young male stranger touching his leg as he moves onto a crowded theatre bench next to him perhaps accidentally but imaginably because, as it seemed to Sergio, ‘in a sensation received together with the swell of music, that the boy was touching him deliberately, for the pleasure of it’.[13] There is nothing soppy, that is to say, about the metaphor of heat on bodily contact. Nevertheless we find in the short stories that there are also dangers in how the idea of personal passion is conceived. The chief danger for me lies in the stereotyping of those to whom the paradigm of a ‘hot nature’ is applied. In Windham’s stories, this is frequently in races, cultures and ‘sub-cultures’ marginalised in the USA such as Italian émigrés, ‘negroes’ and the acculturated (at least in bourgeois terms) working-class.[14] For these classes of person seem to Windham to be a long step away from a stifling bourgeois convention such as that pervading ‘reduced’ middle-class Atlanta, Georgia in in the 1950s and 60s of Windham’s early memories of home, conventions are rehearsed in at least one of the stories of The Warm Country collection too.[15]

The stereotypes arise because the marginalised groups I mention above I think Windham finds a greater likeness to him than in Southern USA White Anglo-Saxon Protestant that he was raised in. The identity he finds with Italianate, black and working-class populations (and perhaps sailors) is located in the marked difference he imagines in these populations from white middle-class society. He represents this difference in Emblems of Conduct as a profound ‘feeling that the world was more wonderful than the people around me understood’; stating clearly that he was also ‘becoming aware that I saw things habitually in a way different from the people around me’.[16]

Nevertheless it is difficult now not to find the racial stereotypes he uses troublesome. They seem acceptable when used about the complexities in personal choices about which possible social or racial identities one might introject. This is I think the case of Paolo, the eponymous hero of a story with that name also, who learns to value the warmth of his immigrant Italian identity as if equated with the soft caress of his mother’s hand and of their mutual ability to communicate in Italian which caresses ‘his heart as her hand was caressing his head’. But beautiful as this is, it is shocking (to me at least) when used, even though in possible reproducing the point of view of a stiff and cold white American repression in the character Thomas Williams (surely a first sally against that other cold TW – Tennessee Williams) we are told of his response to the ‘big brown buck negro George’ that, “he admired George’s strong easy body’.[17] What is the meaning of ‘easy’ here to George, Windham as narrator or us? Of course George is represented as lithe and flexible in body, capable of strong hard work but it also carries the hint of describing something sexually available. This hint is all the more troublesome in relation to the focus in the story of the ethics involved in exchanges of money as loan or payment, with which it is obsessed. It is as if the body of George is prostituted, as will, potentially in the future of the very short (2 pages) story, the bodies of the young ‘small boys’, whom, after seeing the suggestion of loose sexuality of adult male sailors in action in a bar, they stand by the highway awaiting passing cars: The larger older boy tells the younger smaller one about how to get a lift in a man’s car:

‘just stand here … the moonlight is enough to see by. You will get one easy. Just be sure to remember when the cars stop not to tell them you are going anywhere. Just say “I’m safe,” or “I love you.”’

At what risk are experiences bought. This story (entitled Night) is a story at the hard end of the exploration of the qualities of a previously inexperienced set of ethical principles bought at the cost of extreme insecurity and risk.

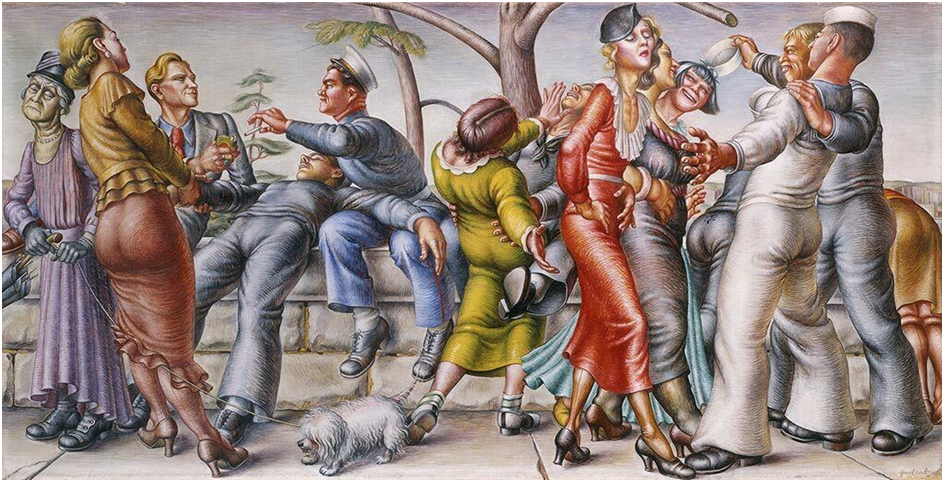

For Thomas Williams, George represents an easy and exciting sexual experience perhaps, even if only in imagination, in comparison to his wife, Lola, with ‘her hair tied up in a towel’, who even in his absence makes Thomas experience his body as in extreme tension: ‘straining his arms till they felt like piano wires drawn through the flesh’.[18] And this tension is precisely I believe because Thomas, as we are told in the story’s opening, keeps in his mind ‘the image of George’s arms at reach’: an image suggesting that man’s ‘strength and ease’ that ‘made [Thomas] forget the reticence he felt toward the white men with whom he worked’.[19] It reminds us that the love felt for an older boy in The Dog Star is to a young man called Whitey (and an emblem then of ‘whiteness’, whose body is stiffer and less yielding than George’s the imagination of another (white) man. Even more telling is the representation of the ‘negro’, with extremely wide buttocks, named Rosebud in the story of that same name. This man’s body is reproduced in terms of images of visceral heat in the experience of rushing internal blood that makes his eyes ‘’bloodshot and red’.[20] Moreover one almost feels, on his Harley Davidson bike, that he is rendered in the image of a phallus, growing firm and as a threat to power as understood conventionally; ‘… more powerful than any of the rich people he served, his waist growing up from the seat of his motor-cycle as firm as the trunk of a tree from the ground’.[21] Rosebud dies starved in the cold of heterosexual encounters gone wrong, his blood feeling like pulses of hot water falling into cold water. These instances are the sources I believe of Forster’s critical commentary about ‘warmth’ in his introduction to the stories. And all of them are about taking social and sexual risks in situations in which conventional morality is barely paid lip service. These are the queer choices of people seeking an alternative life I believe Windham to be consciously exploring, almost as if the burgeoning awareness of a queer community – a community parodied in stories of bisexual sailors (we have to remember these stories are dedicated to Paul Cadmus of The Fleet’s In) in the story ‘The Third Bridge’ and a story which follows it referencing silently the newly forming Fire Island community.[22]

Windham write of references ‘to depravity’ muted on board ship being talk with which the crew is ‘openly obsessed’ on shore in their cafés and bars: ‘Queerness ran through their conversation with the compulsive repetition of a desire always aggravated and never fulfilled’. The conversation goes on to code conversation which criss-crosses between casual but clear punning reference to both heterosexual and gay male oral sex:

“My middle name is sixty-nine”, a slob in the centre of the room would shout at a girl beside him. “they call it eighty-eight where I come from,” another would reply; “I ate her and she ate me.” “Do you want mine?” … “Me no hungry,” she replied blandly. “You hungry. You eat each other’s salami.”

Again, what we need to notice is that Windham is pushing the ethical boundary here between things dealt with by conventional bourgeois morality and things, quite frankly, which are not and which he calls, in the quotation above, ‘queerness’ in a manner similar to post-modern uses of that term in ‘queer theory’ for instance, where the reference is to queering norms not to homosexuality per se.

In 1960 Windham’s novel The Hero Continues, also appears in publication in the UK. It is not a work I value as much as i do others by Windham, and although I think it bears relevance to my interest in other pieces, its aims are not ones I believe that I have captured yet.

Nevertheless one of the novel’s aims is to expose in the fictional character Denis Freeman a trait that Windham increasingly felt to characterise the later work of Tennessee Williams – a desire to write with his eye on securing and maintaining an audience with the kind of substantial income that goes with popularity. For the purpose of art is to probe ethically life as it is lived in Windham, as we have seen. In contrast later work by Williams can be conceived of as being obsessed with the security of popular achievement and a concomitant lack of the kind of daring jump into the unknown in life that renders art great. Such art fails to be moral because it ignores those daring possibilities in form, style and content. This is reflected in Windham’s view, in his memoir on Williams of Williams’ supposed attempt during the production of his play Camino Real to keep ‘himself invulnerable’ and narrow ‘his awareness to “the one big thing, which was work,” …’. Such a weakness reflects too, Windham thought Williams loss of the credo which once motivated the art of both but now, only motivated Windham, although at the time that latter still:

… assumed that [Williams] retained the belief, which I shared, and which he had put into words a few years earlier, that it is a mistake for an artist to think that writing “is something to adopt in the place of actual living, without understanding that art is a by-product existence”.[23]

This tendency is shown in its genesis and development as Denis Freeman’s physical and moral life is literally dismembered and rots in the interests of remaining secure and unchallenged by love or other significant events we associate with being open to life, particularly, let it be noted in his denial of the value of his one true relationship (felt more by the reader than by Denis), with the male poet, Morgan (named after E.M. Forster perhaps, although not a picture of him) and his willingness to form superficial relationships. In the latter category is his outwardly conventional heterosexual live-in affair with Angela. In this novel tragic decline in a man of potentially great stature is treated as high farce as Denis changes the experience of life itself into a constant hopeless movement to maintain financial security (‘well oiled’ is the term used) by pandering to the tastes of the indifferent and conventional in US society, as in this fine passage of tragicomedy, treating of the unexpected sudden success of his stage play in the influential but shallow national media:

For a week Denis lived in a world of taxicabs. … The days moved as though the hours were carried forward in a chauffeured vehicle the wheels of which were well oiled, and gradually he became aware of feeling that everyone else was progressing in the same fashion. Other people’s irritations vanished. … The perversity of identity had Because a group of newspaper men had approved of what he had done, he was welcomed on all sides. [24]

That this novel is still an attempt to communicate with and rescue Williams from his own restless but well-oiled slip into writing for the sake of security of artistic identity and wealth instead of facing the challenges of making difficult choices about life as the stuff of art is partly part of its failure as a whole as a novel, despite some incredible writing. Windham show the rot in writing as caused by the persuasion of the industry surrounding ‘the arts’: publishers, theatre and film directors – referencing Elia Kazan surely, newspaper critics and ‘hangers-on’ with artists like the terrible Angela. As Denis neglects Morgan’s continuing artistic and financial struggles as a poet. He forces Morgan into expense the latter can’t afford in a lunch and patronises him in ways that remain ideas and never turn into real assistance based on love. For instance he dreams of publishing a jointly authored volume of poems with his luckless lover but falls prey to publisher talk: ‘That night at supper the publisher told him that his idea was not practical. The discrepancy between their situations was too great. The book would have to be Denis’ alone’. Denis is easily persuaded when told by his agent that “what you want to do now is amateur”. He huffs: “ I am an amateur … I am a lover of writing”. But this facile word-play around the Latin etymology of the word ‘amateur’ is as near to a genuine loving gesture Denis now will achieve in life in the rest of this hopeless novel of facile paradoxes accepting the contradictions of conventional wisdom to sweep love – for Morgan and art – under the carpet or eventually usher it unto a lonely death. Here is one of those facile paradoxes from his agent that supports conventionalities in the status-quo whilst talking about radicalism in art: “we want to build a strong wall of business to protect that love”. [25]

That the theme of immorality based on the suppression of marginalised life experience has passed into a critique of the purposes of art and this predominates over a more radical queer critique found in other novels By Windham before and after this one. I believe the lover-poet Morgan to be named after Edwin Morgan Forster (commonly known as ‘Morgan’) for it is the values of Forster as an artist that is set against the trivial and (literally) partial man Denis. Denis treats life as if it were a bad novel using E.M. Forster’s characterisation of bad novels, from Aspects of the Novel, the ‘flat’ (as opposed to the ‘round’ character). The meaning is the same. Bad novels work from flat ‘past experience’ of characters only and not to openness to radical (and queer) rounded novelty and ‘mystery’:

Out of past experience he knew what to expect of his mother and, as simply as he knew what to expect from those flat characters in novels, who at each reappearance repeat their one trait.[26]

But intriguing as it is, I would not recommend attempting to know Windham’s work from this novel as i did initially and nearly got put off. The novel two people, published in 1965 in the UK, however is a different matter and marks a return to radical embrace of a radical queer ethic of bourgeois values and is much more ‘rounded’ in its presentation of Italian young men than in short stories I have talked about above. I will end this long blog then with my assessment of the wonders of this novel – ethical, artistic and rounded human, with a radical queer approach to the interplay of the conventional with the queer.

The story of Donald Windham’s two people is the story of two men, each of whom explores their bisexuality as a temporary (or not – since the question remains open at the end as it does in life) new kind of experience in their lives. Their quest (and questioning) opens up the closed world of moral certainties in which each, in different ways, had once lived. Forrest does not however reject the world comprising of his conventional family life with wife and children. Indeed, by the end of the novel, it is a potential for his future for him after leaving Marcello. But he does reinterpret that life, accommodating it to what he has learned about his own nature and that of societies like those of Rome, of which he had once been ignorant. His understanding of his wife’s loving knowledge of him is shown in the process to be greater than his own. For the Italian young man Marcello it is a world in which an acceptance of playful sensuality and sex between men (a sexuality sometimes sold to rich foreigners pay for other pleasures of youth) opens up into genuine choice for his future as he questions whether he should follow the path into heterosexual marriage prescribed as his future by his bourgeois family but also accepted by his society as compatible with that bisexual former life.

And this novel is based on worlds, those spaces inhabited by people and shaped by psychosocial cognitions, which touch momentarily and know not if their paths will continue as one or separate forever. Those worlds are shaped by the psychosocial, I’d argue because we can only continue to live for long in a world we understand or believe that we may do so at some point. In this novel Forrest is a white, American Protestant, middle-class, and apparently heterosexual man though undergoing life-transitions. The later started with the abandonment of his New York flat following the flight from the nest by his children and the couple’s projected move to Connecticut, where his wife is at the novel’s opening having, to his surprise, left him in Rome. In Rome, Forrest has few connections and more limited ability to communicate with other persons and their lives than that degree to which he was habituated in his former world. Nevertheless he will try ‘to connect to the city, telling himself he wanted to stay in Rome without his wife’ though ‘the wind touching his cheeks, his brow, his wrists, increased his loneliness’.[27] We should remember that the play with the word ‘connect’ is a direct reproduction of the E.M. Forster dictum that mutual understandings between persons and their worlds (as in Howard’s End) comes, if it is to come, only when we ‘only connect’ our lives and thought, empathically and viscerally.

The other, Marcello, is a white Mediterranean Catholic young man, from a secure Roman family, living in a building distinguished from the others only by ‘its slight air of prosperity’. Marcello like other Italian young men in the novel swims comfortably across Roman districts marked by class, status and financial security but Forrest sees his sexual contact with Marcello as forcing confrontation of his own fear of otherness in the boy’s world, whether in the disapproval of a ‘respectable family’ or in being placed together with the boy, and possibly family, in a ‘criminal world, with threats of blackmail’.[28]

When Forrest and Marcello connect it is a sexual connection in which neither finds much space over a long duration in time to connect in other ways to each other or their motivating cognitions. It is as if they continued in separate worlds from which each spied into the other’s world for clues that they could understand. The novel is after all throughout about the means by which persons, cultures and other diverse groupings succeed or, as is more usual, fail to communicate, wherein language difference is the most trivial of the barriers faced. Such failures to connect are tragic in Forster but also potentially in this novel were not such an achievement of crossing a cosmology of worlds that it is. Windham marks this by the unobtrusive appearance throughout the novel of links between Marcello’s and Forrest’s world coded in the name of Giordano Bruno, the medieval Neo-Platonic cleric, philosopher (and ‘cosmologist’ in some accounts) with whose thought there is tangent of relevance that remains nevertheless mysterious and difficult to tease out. Marcelo’s well-heeled family live in the Via Giordano Bruno, a very real street in Rome (see the collage below):

Though the reality of the location allows great play with Forrest’s (and the reader’s) curiosity about the place equal to the difficulty of finding it in a pre-internet age, the name of the philosopher performs in other ways in the connection between this couple (if that is the correct term). For instance as Marcello queries the puzzles set by Forrest’s behaviour (puzzles at least and in most quantity to him) of being potentially involved ‘in complications that he would not want to be involved in’ he wonders about the meaning of the ‘coincidence of the American’s being interested in Giordano Bruno’ seeing this interest as mutual cover for explaining his liaisons with the older man to his near fiancé, Ninì.[29]

Forrest’s interest in Bruno is important and is motivated by questions about the otherness of this thinker, so central to the Italian Renaissance and intellectual thought, scientific and artistic, in Europe which resolves itself in an ill-understood, and unevenly communicated in polyglot language of how one world understands another, and ultimately as part of that one person understands the other, such as Bruno who for eight years attempted but failed in prison to come to concord with the Pope before he was burned to death in the Campo dei Fiori, where his statue (see above) now stands. This interest in Forrest has analogy with his musings about what he understands and what he cannot understand about Marcello and this quotation about Bruno comes from a moment where the mutual misunderstanding is at a height, which I cited above which citation comes from the same page of the novel on which the quotation below begins.

He tried to think of Giordano Bruno. … He had explained to various people, sometimes in Italian, sometimes in English, what he wanted. Bruno had been arrested and locked in Castel Sant Angelo. Eight years later, he was brought out and burned alive … It was this position of Bruno’s as a man who is sure he is in agreement with authority, and who will not falsify his declarations to achieve a nominal accord, that interested Forrest. … If opposition is inherent between two parties, a lifetime may not remove it, but this had begun with the two parties in accord. How had there come between them a difference that was insoluble and yet they could not pinpoint and confront each other with? …[30]

I cannot pretend that Giordano Bruno’s role in the novel is central – indeed it, like much else, has a lot to tell us about the common questions about bad faith between persons, grouping and worlds that leads to collision, violence and oppression. Even when the man is first mentioned it is in relation to cultivated misunderstanding between persons, for this is when Forrest requests a recommendation for a permit to read unpublished documents by Bruno in the Vatican Archives from a cardinal he meets at a society party in Rome, which ends with a rather coy offer from the Cardinal in a discourse ‘given jovially, with smiles, almost with laughter’, to ‘find him, if he wished, a gifted unprejudiced student of theology’ to guide and help Forrest. This offer of a young man resonates at this early point of the novel because already by this time Forrest has been eyeing up young men, with surprised pleasure, at the Spanish Steps.[31]

And the ostensible reason for the Cardinal’s offer is also predictive of later tensions between the two people who make up this novel’s content – the fact that different worlds separated in space and time cannot understand each other. As the Cardinal says, Forrest might, even if allowed access to Bruno’s documentation, find them illegible since ‘they would be in such bad Latin that unless he was an optimum scholar of the vagaries of medieval Latin, most unlikely of all in a non-Catholic layman, he probably would be unable to read them’.[32]

Now I tend personally to perhaps overestimate the use of abstruse reference going well beyond text in writers I admire but one statement from Bruno’s magical cosmology certainly illustrates my critical theme and I prefer to think Windham, a voracious and curious reader knew that. For if Bruno scandalised a strict belief in the Creation by indicating that the universe is made up of multiple worlds, he made it worse by a statement such as this cited in the Wikipedia article on him: ‘Bruno wrote that other worlds “have no less virtue nor a nature different from that of our Earth” and, like Earth, “contain animals and inhabitants”’[33] That is he promoted a view that different worlds might in the end find commonalities more interesting than difference, and thus the progress of the world might occur differently, just as Forrest’s world will be different after touching that of Marcello.

There is so much that is rich in two people that this blog could go on forever. But we can end with two main areas worth some genuine learner’s development. First that this novel does deal with ethical situations that arise contingently in the real situations described and which played around his life concerns such as inequality in relationships related to differences in age and access to disposable income, which also touches on the theme of male prostitution that skirts this novel. Marcello is not poor but his allowance from his father restricts his ability to fulfil his desire to purchase such as a Fred Perry sport shirt (still a going concern) that would meet ‘all the specifications’ he wanted.[34]

Forrest begins the relationship with Marcello by casually giving him money after sex, but the move to personal gifts also suggests a dynamic in the relationship, even if it apes a father and son relationship. Indeed I think a central truth in the marginalisation of queer same-sex relationships is that queer desire is failed by the conventions held most, because it secures their power when they have it, entitled older person, such as biological parents but also other elders in a conventional power relationship over them. In summary I think that we cannot create a simple didactic morality around the role of money and age in sexual relationships for the absence of such simple lessons in moral life is precisely the ethical complexity of which this novel convinces us. It spins a dialectical discourse which creates new and nuanced ways of thinking about the nature of value in what is exchanged between queer partners. The most stunning example of this is from Chapter 8, where Forrest queries the meaning of the gifts that interpret the substantial material of a relationship, in terms of use, exchange or symbolic value systems. I do not want to make conclusions on this but urge any reader to face the issues in this startling revision of convention. Take this part of it, for instance, where in comparing gift-giving between he and his wife and that between him and Marcello, is thought is recorded indirectly:

How strange that I cannot give him something of value by giving him gold, Forrest thought. By giving him money, which is the symbol of gold, I can give something that he wants. But by giving him gold, which is the symbol of value, I cannot. It is what can be used and disappear that he wants. His life is still that far from the impractical and satiated; the conventionality he longs for is still that unsophisticated. … he certainly loves money. But he prefers choosing what he likes, not what is expensive. And how many people dare to do that now when they have the chance to do otherwise? Who nowadays quite believes that value is not equivalent to price?[35]

All I want to show here is that the conundrum posed in my title from Windham’s autobiography is being worked through here, where queer life experience necessitates a reshaping of ethics where morality is not tied just to questions of security but to questions of open self-determined desire

Secondly and finally, I want to briefly look at how this novel deals with issues of identity and choice, for I believe this to be crucial to its existential position (possibly inherited from a love of Camus). Emotionally demonstrative Italian boys in the opening of this novel surprise older American men as much as they do the English in Forster’s Italian novels, especially in the indirect and transposed desires within Where Angels Fear To Tread. In the case of Forrest’s first sight of Marcello that demonstrative behaviour becomes almost an indifference to sex/gender, and active or passive sexual expression, something new that refuses labels or prescribed moral responses. This is described thus just prior to the two people’s second meeting:

He considered their meeting a phenomenon, a sport of Rome, not a personal attraction. He could not find a category to put this new desire into, just as he could not fit the boy into any category he knew. The boy’s figure, lean and rounded, evoked neither masculinity nor femininity, rather the undivided country of adolescence; and his silent receptivity, open equally to tenderness and passion, spoke of no special desires, but of a need of love so great that it prevented him from asking for it.[36]

This failure to categorise either the relationship or its objects that sings through this novel is what makes it a queer novel, wherein there need be no recourse to specialised binary categorisations like homosexual and heterosexual, which is, I think, still the case for the identity of both people at the novel’s conclusion. The resolution is a non-resolution based on the acceptance of life opportunities and the unforeseen challenges they pose, as suggested here where Marcello’s facial features when eating in a trattoria with Forrest:

… expressed acceptance instead of expectation. He might be the father of a family, eating supper at the end of the day, glad to have a moment alone at the table while his wife put his children to bed. … The sparkle behind his eyes, the wondering if there is anything that life is not capable of, was replaced by a reflective wondering if, after all, this could be all. It was not a look of disappointment. The incredulity had been in his expectation; it was not in his acceptance. … Let life be as wonderful as it could be, he would accept it. But he waited for life to make the extravagant gestures. His own moves, however bold, were mundane. … It is ordinary to love the marvellous; it is marvellous to love the ordinary.[37]

What in this passage is about fixed identity? It is rather about acceptance of the fluid potential of self and other across time and space, geography and history – and this is the ordinary which is the truly queer because it refuses prescription of what is ordinary, replacing existential experience with cognitive expectations of what life will give. It is central to my critical theme regarding this writer’s achievement which is to suggest that openness to life events will always trump prescribed cognition that arise in the form of shaping plans and expectations about that life.

It matters to me that Windham believed that this ethical shift in Forrest’s thinking is related to the rejection of cognitions that condemn sex between men as a potential whether enacted or not according to the contingencies life throws up. Forrest could only accept change in others (like his children and wife) if he accepts the validity of every aspect of their relationship and its contingencies in different world circumstances which ranges wide amongst such exchanges as those of money as well as that of affection, and of course sexual desire. As he considers plans for a future for himself in the light of change in Marcello, he realises that their relationship has been also one with himself, in which he accepts different forms of the expression of relationship that are by necessity, for it is true of every product of ‘life’, ‘not clearly defined’ and this may involve releasing any demand on the permanency of the presence of the beloved in actualised space and time. He will let Marcello go and still love him in some way:

Love’s power is that it lets you exist outside your own body. … Its biological end is the creation of a new body, and because of this it has been taught that love between men should remain chaste. But life is not so clearly defined. Forrest had suffered less from an aberration of thought when he felt a part of himself was leaving each time with Marcello than he had suffered from a failure to accept what was happening. He accepted it now. But it did not make him chaste. He was glad when he realized that, despite the change in their relationship, and whether for money, or desire, or affection, Marcello had come to the apartment that day, as he had come in the past, with the specific intention of going to bed. … And, although he had not given much subsequent thought to his drunken loving to be reincarnated as a Roman, he sensed that it was at least in part himself that he held in his arms that afternoon.[38]

I don’t deny that there is some muddle in thought here considered as thought alone, but that is not how we consider effects in art, which are those of shifts between the expression of meaning, sensation and feeling. This passage is in fact showing the process of changing one’s mind in ways that allow one to leave behind what has seemed essential to your identity because life and its demands are not defined but must respond to time. Its purpose as writing is fulfilled in the final chapter (Ten) in which the parting of two people is the conclusion of their tale but not of life. That parting might be read as heartbreaking with its bald shaking of hands and an ambiguous kiss on each cheek (which might be sexual, familial or cultural) but it is none of this singly since it gets absorbed in the muddle of ongoing time as do Forster’s plots at their best (which is not always). We see their ‘Arrivederci’ as a single hard-to-interpret moment in which otherwise this is all that can be said: ‘There was a confusion of porters, hawkers, bus drivers, passengers’.

If you read one book by Windham, read two people but if you can, read more. He is a queer classic too long neglected.

All the best

Steve

[1] Donald Windham (1996: 150f.) Emblems of Conduct Athens & London, Brown Thrasher Books, The University of Georgia Press.

[2] Ibid 8f.

[3] Ibid: 195

[4] Ibid: 60

[5] Ibid: 208

[6] Ibid: 209

[7] Ibid: 76

[8] ibid: 150f..

[9] Ibid: 151

[10] Donald Windham (1965: 7) two people London, Michael Joseph

[11] Donald Windham (1960a: 9f.) The Warm Country London, Rupert Hart-Davis.

[12] Tennessee Williams and Donald Windham (ud: 50f.) You Touched Me New York, Samuel French, inc. (reprint of 1947 version)

[13] Servants with Torches (page 78) in Donald Windham 1960a:75 – 90

[14] Of course I am uncomfortable with repeating the word ‘negro’, even in citing it from 1950s white discourse, although Windham almost certainly felt his use of the word to be avant-garde and a reflection of the marginalised great black and, in some cases queer, writers of the Harlem Renaissance who resisted white and bourgeois value systems. Indeed it could be worse. The queer white writer Carl Van Vechten entitled his 1926 novel of the liberation of black Harlem Nigger Heaven.

[15] I am thinking primarily but not only of ‘Single Harvest’; Donald Windham 1960a: 175 – 192.

[16] Windham 1996 op.cit: 150

[17] The Warm Country p. 119 in Ibid: 119-131

[18] Ibid: 127

[19] Ibid: 119

[20] Rosebud (page 11) in ibid: 11 – 31.

[21] Ibid; 13

[22] Ibid: 133 – 145

[23] Donald Windham (1987: 250) Lost Friendships: A Memoir of Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams, and Others New York, William Morrow & Co. Inc.

[24] Donald Windham (1960b:55) The Hero Continues: A Novel London, Rupert Hart-Davis.

[25] Ibid: 57

[26] Ibid: 151

[27] Donald Windham 1965 op.cit: 23 (and preceding pages for details of the world re-described here)

[28] Quotations are found ibid: 80 (and preceding pages for details of the world re-described here)

[29] Ibid: 91f.

[30] Ibid: 80f.

[31] Ibid 19 (the first Spanish Steps incident is ibid: 8)

[32] Ibid: 19

[33] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giordano_Bruno

[34] Ibid: 101

[35] Ibid: 148

[36] Ibid: 33

[37] Ibid: 173f.

[38] Ibid: 183f.