Javier Portús, introducing the book that celebrates the Prado’s first celebration of The Spanish Portrait explains that ‘some readers may be surprised to see some pictures that are not portraits in the obvious sense’ but that they are included as an ‘opportunity to reflect on the boundaries between portrait, reality and representation’. That opportunity he goes to say acknowledges the ‘flair for naturalistic description’ in the history of Spanish art.[1] This blog insists that those boundaries are nearly always porous and need added to them the liminal cusp of boundaries of the portrait to paintings that evoke ‘description’ also of the imagined supernatural wherever it occurs – in religion, political ideology. It uses as its case studies examples of ‘portraits’ currently in the Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland: from Reflections and Discussions in my free time on some of the Works of Art, as part of a personal learning project related to the Golden Age of Spanish Painting (No.7).

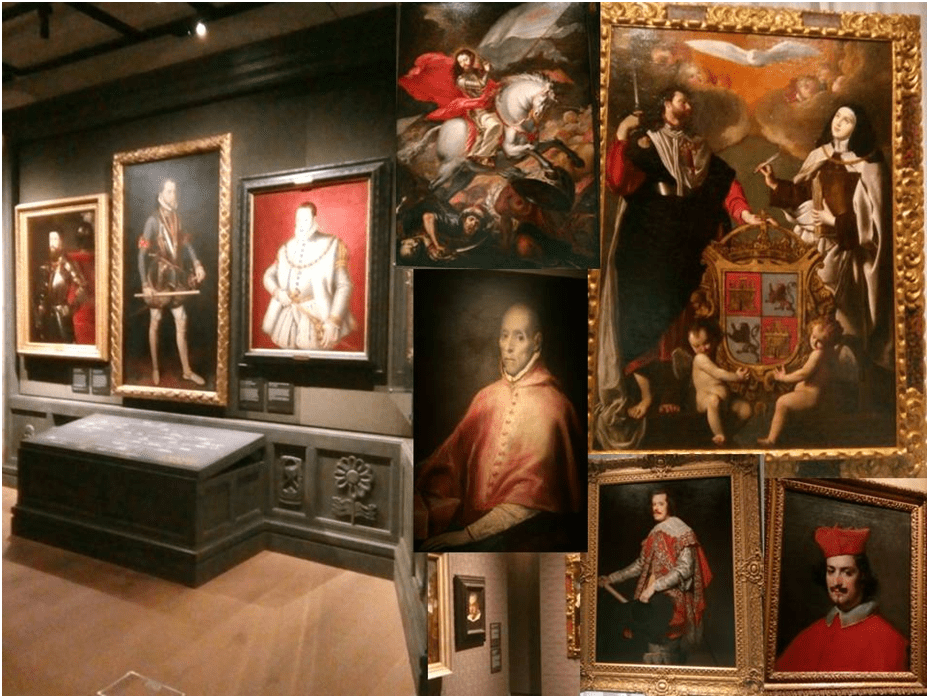

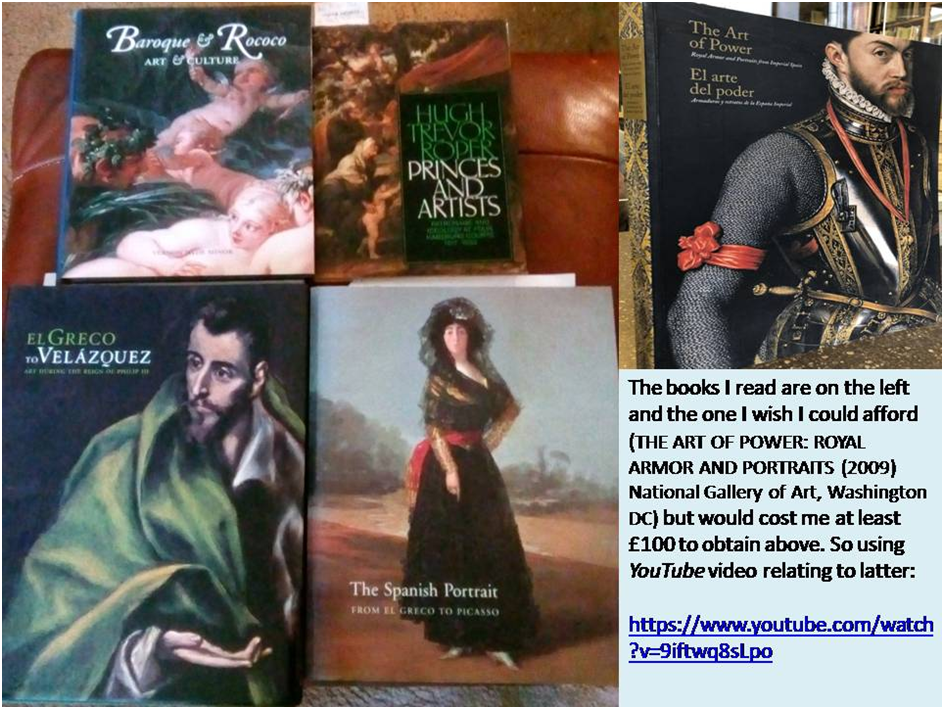

This blog has been long in gestation because the plasticity in defining and evaluating the portrait. The problems of defining the ‘portrait’ affects us from the offset even in considering a limited sample of possible examples such as those found in the Spanish Gallery. This is the case whether we seek a definition that is either, to use Shearer West’s analytic approach, either an a-priori to looking at examples of actual paintings and ontological (‘What is a portrait?) or an a-posteriori description of the functions that known portraits serve (West uses in this typology labels for functions such as ‘work of art’, ‘biography’, ‘proxy’, ‘commemoration’ or ‘political tool’).[2] However, the link between definitions of the ontology of this genre and prescribed judgements of its value have formed part of its history in all Western European countries, since artistic genres are so often understood as forming an a-priori hierarchy of value and significance, especially after the advent of national Academies of Art in the eighteenth century. Examples of such hierarchies pre-existed, though in different forms varying across time, cultures and place, the Academies of course.

This is I think why Vernon Hyde Minor in 1999 spoke about the subject of portraiture in a chapter (and the scare quotes in the title are essential to the message of the chapter as a whole which also deals with still lifes and genre painting) entitled ‘The “Minor Arts”’.[3] A number of reasons are given in this chapter for why some artists at least did not think of portraits as automatically ‘minor’, despite the assumptions of others. First, they were valued because they dealt with a ‘human subject’ rather than one drawn from animal or inanimate nature or the built environment. This reason was given new prominence, as if by divine sanction, by the Spanish pupil of Michelangelo, Francisco de Holanda, in the sixteenth century, because the human form, and especially the face (being created in the ‘image of God’), was given central importance in the revival of Neoplatonic thinking in the Renaissance.

Secondly, some artists, Durer for instance (who phrased the idea as follows), believed portrait art was a means of preserving ‘the likeness of men after their death’, enshrining in the definition of this genre the value of art as a tool that enabled not only commemorative memory of a life but the modelling the mode of that virtuous life as an exemplum for future ages. Not least the virtuous life of the artist himself is modelled and hence Durer’s many self-portraits. Meanwhile Raphael’s preservation of contemporary faces (such as those of Michelangelo and Sodoma playing in ancient roles from classical history in his The School of Athens, or, as discussed by Minor, the face and demeanour of Castiglione in a portrait are examples of such life, thought and value preserving functions of the portrait and its extended genres – such as that of the group portrait.

However, an even more central issue, as the seventeenth-century progressed and both nascent Empires and nation-states were in formation was the use of a portrait in order to allow rulers and leaders of Church and State (or both as in the case of England) to ‘radiate an aura of power’ on representative individuals like kings, ‘prime ministers’ (the first being the Count of Lerma in Spain under Philip III but including the more famous ones in Louis XVI’s France – Richelieu etc.), popes and cardinals.[4] A further reason allied to the latter, although not mentioned by Minor, is that the genre which was to become of supreme value was that of historical painting could have some categorical likeness to the portrait. Such paintings of course do not use a singular interpretation of the term ‘history’ but were any picture that told a (his)story of national significance that may be in part mythical, although a myth that was sometimes validated, if not actualised in history but validated by antique sources or both, such as the story of the establishment of the Age of Gold in Vergil. But though in Spain, according to Portús, Carducho was consistent in his view that the ‘great and eminent painters were not portraitists’, the more popular theorist of painting (and painter) Pacheco was to show the way in which the addition of additional figures or interior, or exterior, architecture can make something ‘we also call … a history painting’ out of any portrait. This point is taken up later in art ‘theory’ (if I can use this anachronistic term) by painter and biographer (of sorts) Palomino. Portús, summarising these ideas, also shows us that this is how and why, Las Meninas is such a great painting based on creating a ‘theology’ of the role of portrait painting both as product and process.[5]

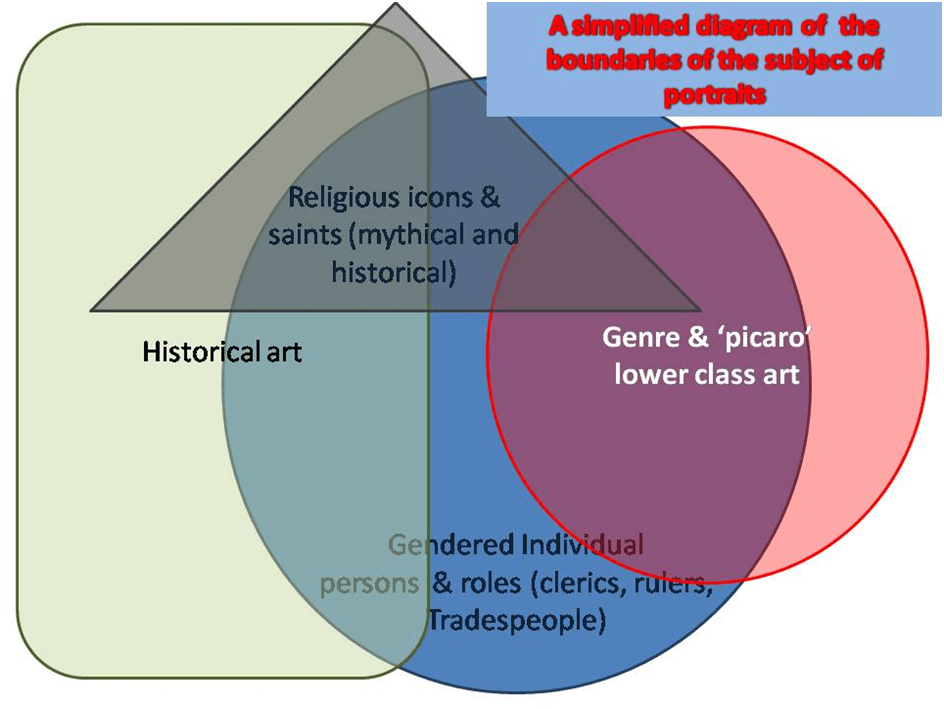

Such complex issues have plagued this blog in its preparation. Historical (in the sense of both the secular record of world events and the grand narratives of allegorised mythology and religion) and ‘genre’ painting both play a part in the history of portraiture in making it what it is and interpreting its functions. Although grossly over-simplified no doubt I am proposing here that we can visualise overlaps between the subjects in the sub-genre(s) of portraits which complicate both its functional and ontological definition thus:

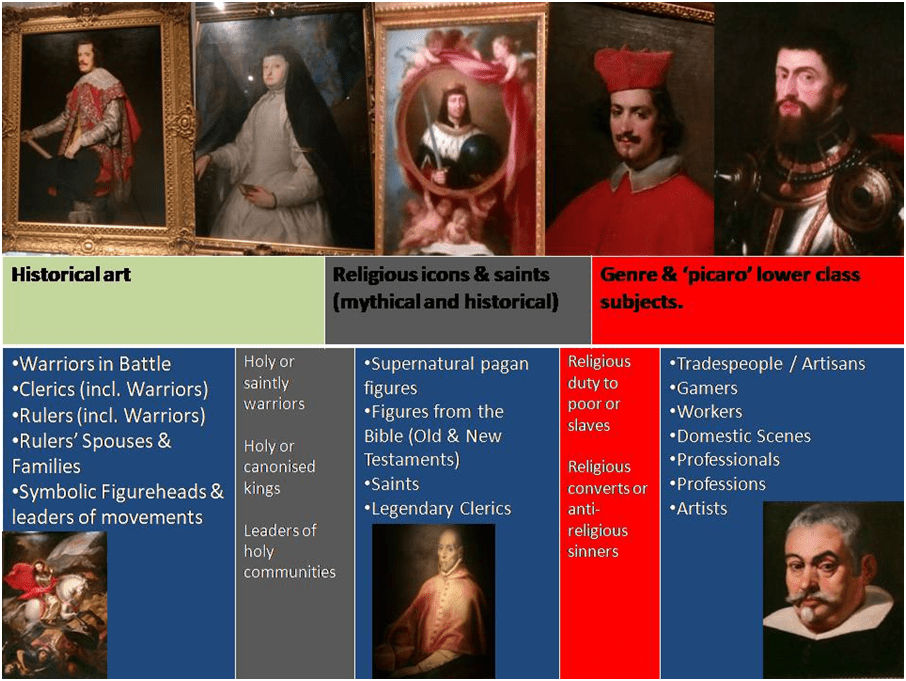

I have also represented it in a different paradigm in terms of its subjects and character types in the following diagram. It is a response in part to the truth of the statement of Gabriele Finaldi that, despite the comparative rarity of his ‘portraits’ considered in a narrow sense, all of Zurbarán’s ‘figure paintings are portraits’, observing that: ‘His saints and visionaries, monks and martyrs are distinctive individuals based on the study of the physiognomies of particular models’.[6] However, since this blog cannot be limitless (though it might look it more than it should) I will arbitrarily not deal with unnamed lower-class individual here nor saints and martyrs, where at least their function is not to a large degrees a ‘political tool’ and helps in the discussion of other examples of the monarchs of states nearly theocratic in their self-definition.

A key picture to start with however in using some of the terms in my diagram is a royal portrait which represents the iconography of holy armed warrior. Indeed this idea is a traditional one in both politics and the history of visual and literary art It is one of the functions of the idea of the ‘King’s two bodies’. For symbolism of setting, accompanying objects or clothing worn constitute the body (social or metaphysical or both in their nature) as a set of meanings and values quite separate from the assumptions of an individual personality we also assume and seek in looking at a portrait. In every painting of a ruler for instance the appearance of the whole picture must serve multiple functions. We can start with our look at portraits in the Spanish Gallery’s collection with Rubens’ work, described as ‘after Titian’, portraying the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V.

Hugh Trevor-Roper is inclined to believe that Charles V looked to Titian as his ideal of a court-painter because neither sitter nor artist was inclined to over-use of ‘all kinds of mythological and allegorical figures’.[7] The same applies to Rubens who succeeded Titian as court-painter with the same court title huius saeculi Apelles (the Apelles of his age). Yet Trevor-Roper overplays the distance between these later court-painters and earlier more extravagant allegorical reporters of Hapsburg ambitions such as the sculptor Leone Leoni. No doubt the iconography of ‘ancient grandeur’ in the coronation of Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor in 1530 that employed imagery indicative of the ‘Golden Age’, according to Vergil, of Emperor Augustus’ was highly elaborate. But that it was more elaborate does not mean that Trevor-Roper’s definition of Titian’s greatness which he sees as lying in part ‘in his ability to see and portray the whole personality of a man’ has supplanted the allegorical and mythological’ by a version of what we now call individual personality. The allegorical and mythological has instead been sublimed into less obvious forms. The mystical and symbolic body of the king remains part of Charles V.

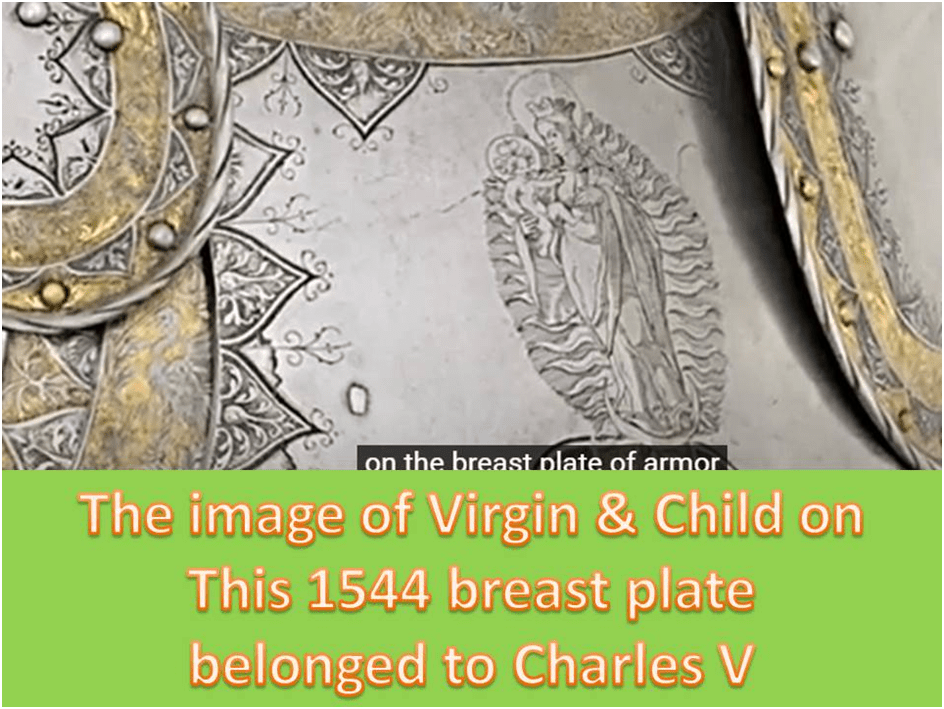

I think we can, for instance, see it in the armour and insignia he wears and in one sense is in a relationship of becoming in the type- figure of Miles Christianus, the Christian Knight of Erasmus’ famous work of devotion’.[8] This is reflected in the representation of Charles in armour as a militant holy warrior. We would, of course, be wrong to see the donning of armour for a portrait as a neutral choice until that armour is adorned with decorative symbolic art. It is already a symbol as Trevor-Roper’s reference to Erasmus shows. Such armour is only the more obviously indicative of the Miles Christianus when it bears symbolic references as in the 1544 suit of armour prepared for Charles V and bearing the inscribed image of Virgin and Child and in the Armoury Museum in Madrid.

Such imagery remained current for Philip II, Charles son, as King of Spain as a comparison of the two plates shown below from the same source. Both plates below depict the Second Punic Wars between Scipio Africanus (portrayed almost as an armed medieval knight) against the Carthaginian Hannibal. It was easy to see here an analogy between the Christian forces of Europe and / or Spain and a Moorish, Ottoman Turkish or any other ‘alien’ (othered) enemy.

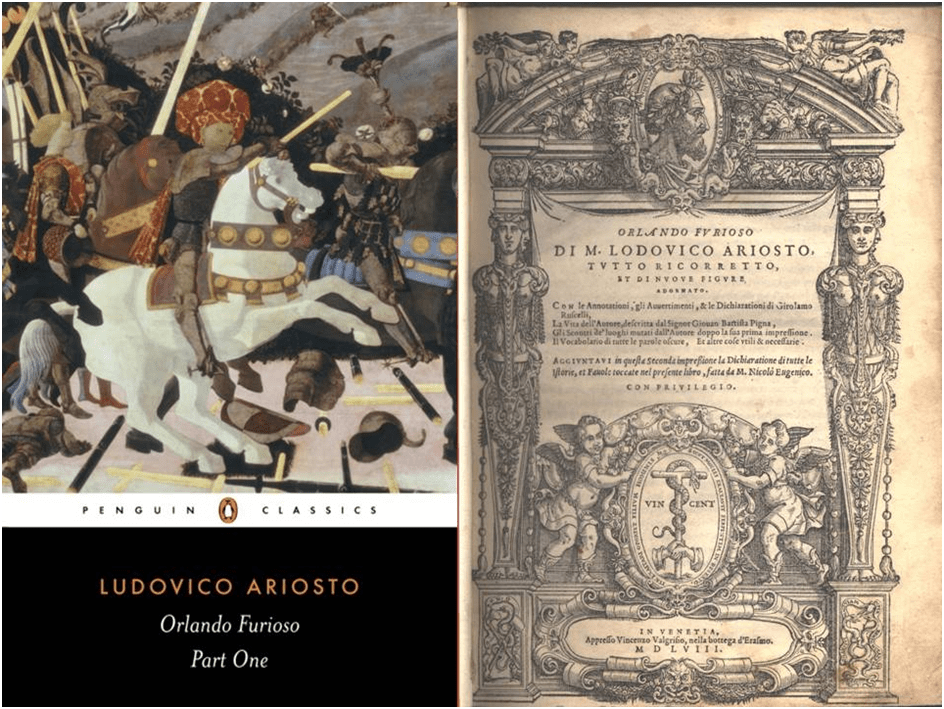

This aspect of armour as the representation of a divinely validated Christian military force was even more refined by another source of imagery for the concept of imperial Christendom, Ludovici Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso. Trevor Roper cites the latter’s representation of Charles as ‘the wisest and the justest emperor that has been, or ever shall be, since Augustus’.[9] Those words appear as a description of Charles V in a section of Canto XV in which the narrator uses a sea-voyage of one character, count Astolfo, to predict the sea-journeys by explorers which would establish the global Spanish Empire, and uses it (as indeed it would be used at the time) to justify Imperial connotations of the role of Charles V in Europe as Holy Roman Emperor. Elsewhere Ariosto likewise implies that he is the most transcendent of ‘Christian knights’ and the best chance in his contemporary world of awakening ‘response to the ideals of Christendom and chivalry’.[10]

God’s will it was that in the ancient days

This path across the globe should be unknown;

And seven centuries must run their phase

Before the mystery to man is shown,

For, in the wisdom of the Almighty’s ways,

He waits until the world shall be made one

Beneath an Emperor more just and wise

Than any who since Augustus shall arise.

A prince of Austrian and Spanish blood

Born on the Rhine’s left bank, behold, I see:

With valour such as his valour could

Compare, in legend or in history.

Charles V appointed Titian his court-painter titling him not only huius saeculi Apelles (as before mentioned) but with various medievalised sinecures such as the ‘role’ of Count Palatine, Knight of the Golden Spur and eques Caesari (knight of Caesar). The trappings of medievalised antique armed knighthood were shared thus between painter and sitter. Let us look again at the Ruben’s version of Titian:

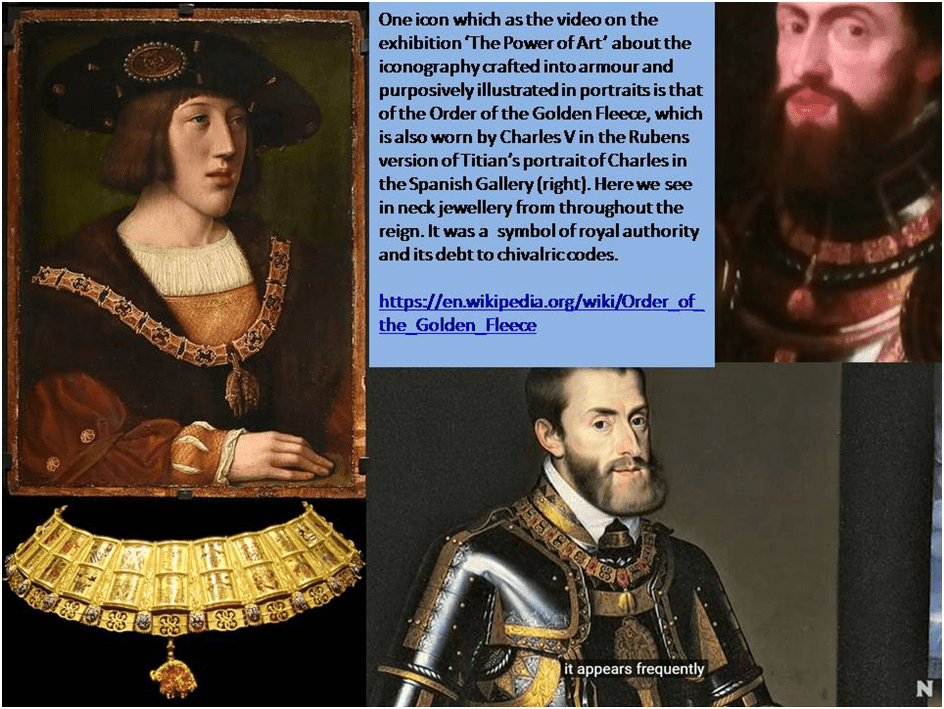

As in all portraits of Charles and later Hapsburgs he is adorned with the emblem of the Order of the Golden Fleece hanging from his neck. The symbol is perhaps more clearly seen in better photographs of portraits from throughout the reign where in each a version of this neck jewellery. It was a symbol of royal authority attributing its origin to both classical and medieval origins: aristocratic, dynastic (because derived from the knightly and Greek aristocratic connection to horses), courtly and chivalric codes and values. Since it partook in part of the imagery of the sacrificial lamb, it was symbolic of the union of Christ’s kingdom and chivalric duty. Of course the Hapsburgs always wore it but they wore it to convey their role as Christian Knights, a meaning of the armour it adorned.

Likewise Charles’ armour in our portrait showed symbols of a shield to the sitter’s right top breast and spike to his left (left and right will be reversed from the viewer’s perspective of course) to indicate that the holy warrior was both actively militant and passively defensive against the offence of others (the latter being emphasised by Erasmus). In our portrait the sword is raised in symbolic readiness for offence in the name of Christ too but the defensive helmet has been laid aside, if at a point raised to the same height as the Emperor’s head. Light gleams from the armour in the domain under which lies the man’s heart. So much of this is iconography of the most subtle sort where the King’s social and spiritual body encases the human body and makes it secondary, if not unimportant. Even the grand isolation allowed by the portrait, which often assumes a single sitter, is made symbolically important in my view, because it invokes the idea of unity under one figurehead important to the medieval ideal enshrined in the Crusading defence of Byzantium and the defeat, by the union of rulers under one embodied Christian idea, of the alien other of unchristian values, as this paradigm constructs Ottomans, Moors, Jews, and the example of Carthage in the Second Punic Wars. As Ariosto puts it:

If the most Christian’ rulers you would be,

And ‘Catholic’ desire to be reputed,

Why do you slay Christ’s men? …

Why do you leave in dire captivity

Jerusalem, by infidels polluted?

Why do you let the unclean Turk command

Constantinople and the Holy Land?[11]

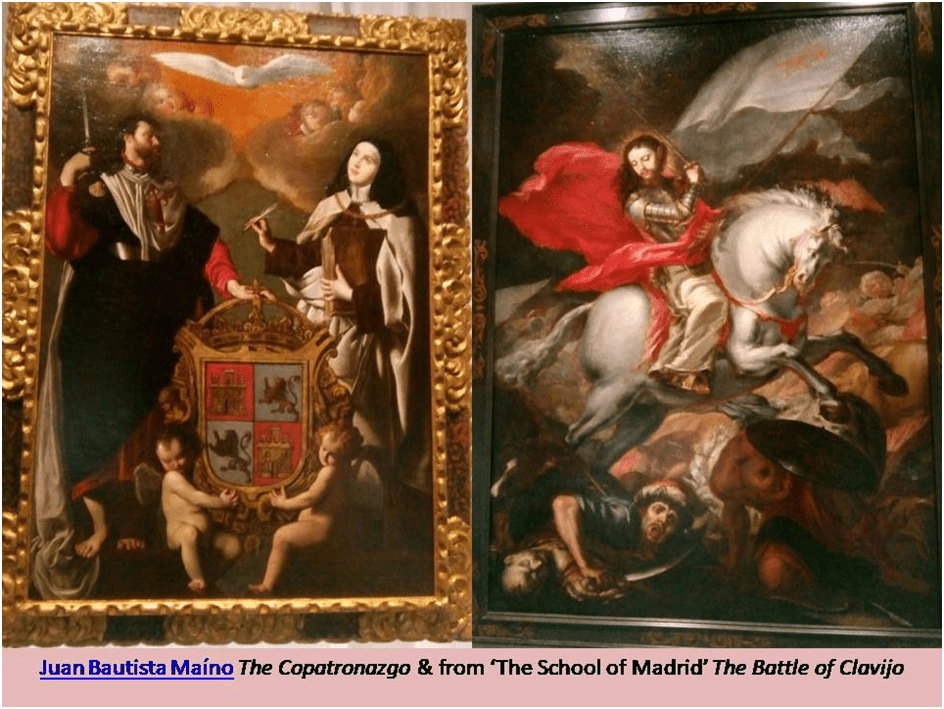

Such ideologies served Renaissance and Baroque Spain with models of the militant warrior. In the Rubens’ portrait, Charles bears his militant sword in exactly the same way as in representations of holy warrior saints, such as in the ‘portrait’ of the apostle Saint James the Greater, whom was taken as patron saint of the nation. A star of the Bishop Auckland collection, for instance, is The Copatronazgo. Of course since it deals with saints, it cannot be claimed to emphasise the naturalism of its models, except in the picturing of their flesh (Saint James unclean but dependable feet – since they are a tool of his missionary piety – for instance).

It portrays highly idealised figures of Teresa of Avila and Santiago Matamoros (Saint James the Moor-Slayer, one of the types of Saint James specific to Spain) and is adorned with the scallop shell associated to his supposed burial site in holy Compostella. Their canonisation as joint patron-saints of an ideologically united Spain had been successfully fought for by both Philip III and Philip IV only for that form canonisation to be early snatched away by Pope Urban VIII in 1629, who commanded that all the images of the two saints together be destroyed’ (though of course this one has survived).[12] This and another painting nearly adjacent to it in The Gallery explain why Saint James is associated with the militant warrior, in very physical martial terms. This further explains why there will be a stress in Royal portraiture on a king armed against intrusion, even when the territorial conquest of Spain was complete (and the scapegoat unconverted Jews and Muslims had been expelled) and the armour had become iconographic of that militancy rather than its reality. The other painting is The Battle of Clavijo (the possibly mythical story of that battle referred to can be found at this link) and creates a knight in equine pose (often employed for the Hapsburgs too) wielding his sword against Ottoman Turks, Moors and other infidels who appear as if in a picture of the Christ crushing the head of Satan under the feet of Man.[13]

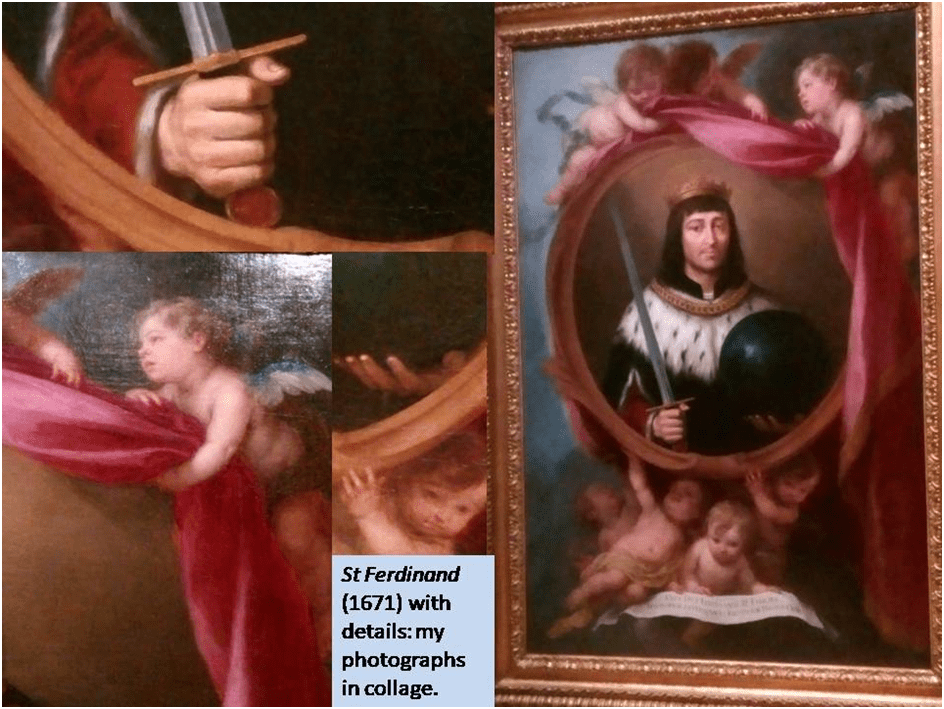

Hapsburg royalty might well choose to be represented in the holy defence by arms of the spiritual might of Spain both through the visionary and the armed military Holy Spirit, an ideal combination of Christianity armed in defence against unbelievers. Charles V was for instance still fighting Muslim rule across and ‘for’ Occidental Europe as Holy Roman Emperor. Sometimes this is done without the subtlety of Titian or Rubens. In Spain the example of the thirteenth century Ferdinand III of Castile is also of interest here. A painting attributed to Pacheco (and it fits his penchant for adding other figures and architecture to make a portrait pass as a history painting and vice-versa) depicts the Moors in the thirteenth century surrendering Seville to the newly united Castile and Leon. The painting shows the King in armour receiving visionary Vindication from the Virgin Mary in the heavens, whilst a fleet is being building in the mouth of the Guadalquivir, and recalling to me the theme in Ariosto which combine Imperial naval exploration and conquest in the New World with internal union of a Christian Nationhood.

This explains the passion of Hapsburg James IV for the canonisation of Frederick III. On the success of that campaign an idealised portrait of the warrior – king, co-opted into Philip’s ancestry, was commissioned from Murillo, in a painting near to the putative Pacheco in the Gallery together with the book bearing a print of the ‘same’ image. The issue here was to make myth and its iconography seem real by trompe l’oeil effects and I have already written about this in an earlier blog.

Trevor-Roper very much distrusts the use of imagery like that of Charles V when applied to later Spanish Hapsburgs, particularly Philip II, which he represents as conservative, back-looking and lacking dynamism: ‘Stare super antiquas vias: to stand firm in defence of ancient values, ancient austerity, Roman philosophy, that was the philosophy of Philip II’.[14]

The iconography of the armour in this painting however is simply inherited from Charles V, his father. The armour made in 1551 was actually worn, says the Gallery caption, in the Battle of Saint-Quentin against France in 1557. The armour’s decorated cuirass bears a flaming Virgin and Child at its centre together with iconography, and the neck jewellery, of the Order of the Golden Fleece. The painting is nowhere as distinguished as Rubens’ but of that we can’t judge Philip or his conception of the King’s social body. However, it is noteworthy that Philip is not raising his sword in offence as did Charles V and this sword remains decorative. However barring our access to Philip and almost cutting the picture plane in half is a baton of state, a classical fasces in fact symbolising rule and regulation of the law rather than the spirit. Even if this is so, however it does not justify the ways in which Trevor-Roper attributes Philip’s austerity to an inferior personality aping but never equalling his father. The King still has two bodies but the meanings of the social and spiritual body change for many more numerous and interacting reasons than one man’s character. It may in fact be that later formulations of autocratic and centralised monarchy tended to emphasise the import and significance of the ‘image’ of the King over his person.

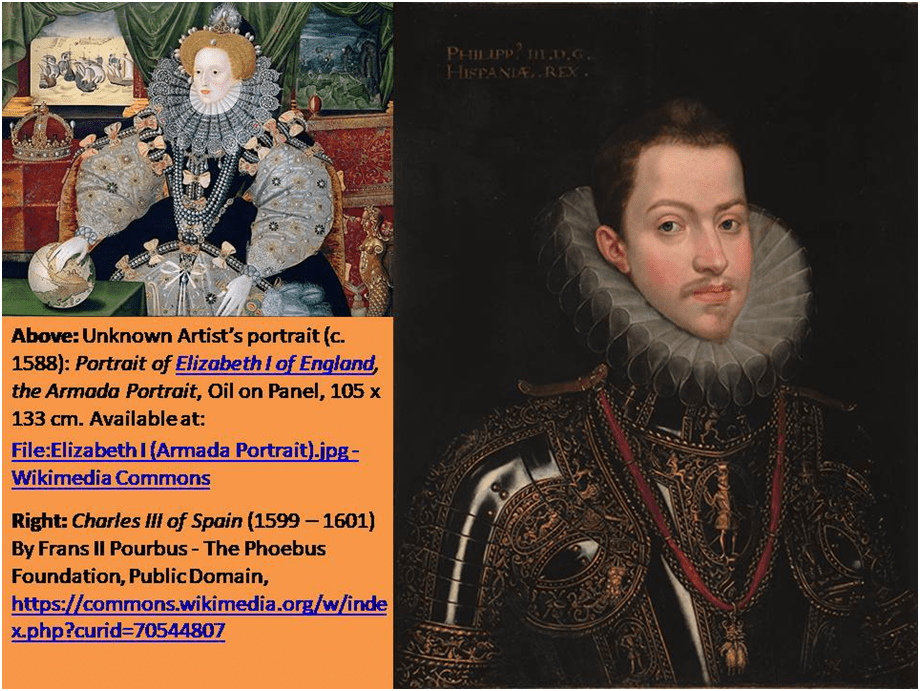

By the time of Philip III monarchy in Spain might look for models of centralised power in its own assertive and over-riding control of its own Empire rather than to Empire as a trans-national ideal, of which Charles V was the last adherent. A case in point was England which, in the hands of Spenser, nationalised (and Brexitised) the notion of unity of divine right over territorial acquisitions in Ariosto. Philip II saw England as an arch-enemy but England became under Philip III to be looked at with envy in places where monarchical power served aggregate kingdoms and colonies, as in Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. The Duke of Lerma who controlled Philip III’s governance of Spain until his eventual disgrace, for instance, owned a portrait of Elizabeth I and introduced its modus operandi (‘ever-youthful mask, white face, lack of shadow, and form reduced to decorative shape as pattern’) into the iconographic representations of the individuals running the business and show of the court of Philip III: ‘remote and stiff reserve, the glittering display of finery, and archaic formalism’ that ‘turn the human being into a cult image’.[15]

The creation of a ‘cult image’ is useful when the state faces the tribulations when kings, as Philip II and Philip III did in different ways with different tools, aim to centralise power in the state. These ways are described by Hugh Trevor-Roper and Sarah Schroth respectively.[16] One portrait in particular Shows how the two bodies of the Royal Family are conflated in the case of members of them that are in some other ways treated as weaknesses in the system of power inherited through genetic connection alone.

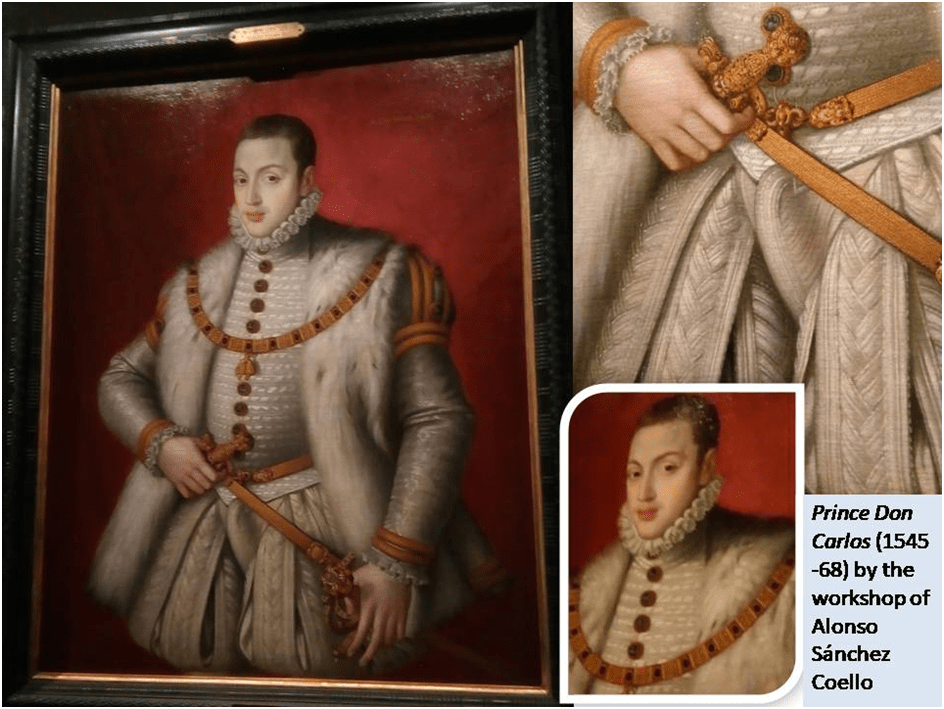

Of course Don Carlos in Alonso Sánchez Coello’s painting is not represented in armour (as he is in the Portrait of Don Carlos by Jooris van der Straeten) but in the grandeur of the supreme courtier as imagined by Castiglione, but as royal leader in waiting his attitude is also one of intended preparedness for military service. His pudgy hands grasp a dagger and sword handle respectively. The play of the rigid cloth of his courtly clothing frames a codpiece that stands between sword and dagger in the line between his hands marked by his gilded leather belt. Of course he still wears the Order of the Gold Fleece insignia but his costume is meant to enlarge and impress his person upon viewers in width, volume and costly and elegant quality. The contrast between this prince’s ‘two bodies’ could not, after all, have been greater. A young man destined for an early death, don Carlos was known not only as weak physically but as a boy whose abuses of his social power seemed to make up for very little feeling of genuine self-worth. Whilst a court-painter creates a symbolic body, that body too shares interpretative ideas of its value that can hide weakness but also display in apparent contradiction – a feeling I get in the contrast of soft boyish hands and military stance.

The same artist creates (for me at least) a similar contradiction in the portrait, currently on loan to the Gallery by the Bowes Museum, of dowager queen Mariana of Austria, widow of Charles IV. This is another fine statement of the largesse of the royal body by Alonso Sánchez Coello although it is of a body spiritualised too – at least by its clothing and the objects had symbolically by the figure.

This exceptionally large and well-fed lady dominates the scene apparently refined by a desire to demonstrate holy piety and retirement from the world. Yet her well-fed body houses a stern eye that is well aware of the power of which it seeks to persuade her viewer. If this is retreat from the world moreover, it is exceptionally luxurious retreat. I sense massive contradiction for instance between the signs of luxury and refinement in the background curtains and the austere of the face and nun-like clothing of the figure. Mariana’s pretensions could, it was believed, allow her to think herself the Queen of Heaven, and here at least was a role from within the iconography with which to identify for a royal consort and protector (of her son Charles II) queen, who was not a Queen in her own right – a Holy Mother. But let’s move back in time and look also to the King of which she was in this painting, the widow, Philip IV.

After Philip II & III’s control of art as a means of propaganda (it is a simplification but one with a little truth) the portraiture of Philip IV is often considered as a sign of decline in Spanish royal portraiture – in its assertion at least of royal power if not of the quality of the painting itself. Jonathan Brown describes Charles as ‘set in a conventional pose, remarkable only for the absence of articles of glory or attributes of military prowess ’.[17] There is the same baton or fasces held at an angle that is almost parodic of a phallic symbol, particularly given how the large black hat is held over the king’s groin area. The sword rests passively against the fine silk clothing the King’s arm. None of this is intentional I take it but is readable partly because the painter seems to concentrate mainly on the reproduction of effects in the representation of the King’s clothing by using an impressionistic impasto technique to show, as brilliantly described by Brown to create the impression of the millinery art involved and its effects in the light. Though Brown does not say this implicitly the focus is not on the impression which conveys the King’s social and spiritual body to all viewers but of the artistic daring and innovation of the artist as he strikes ‘the balance between order and accident required to bridge the distance between artifice and appearance’.[18]

The Dulwich copy now on loan in the Spanish Gallery is sufficiently good to see these effects and its details are as evocative of the folds of clothing and the effects of pressure by objects on such folds to really help us not to miss as much as we otherwise might the original in the Frick collection.

From royalty however, we need to look at what is sometimes called the democratisation of the portrait in which the sitter was a less well-known person of more minor social status than royalty or aristocracy. Sometimes those persons have no name at all but look individualized rather than a type of man or woman alone. The subject-matter of the ‘portrait’ socially was socially wider in the case of saints and martyrs already but this can be looked at as a special case. It is certainly my preference. In that case too, the ideation supporting this group of persons’ social function or image often dominates the individual in countless versions of Saint Lucy and St. Bartholomew. However in the great late paintings of even anonymous persons (even marginalised persons like older people, children and the people of limited physical growth who were forced to become objects of fun as well as service in the Spanish court) by Van Der Hamen, Murillo and Velázquez the person and social type are both still the dual ‘subject’ of each portrait painting, I’d assert. The most complex version of this is Las Meninas, wherein court ‘dwarves’ and people serving the King and Queen, including the self-portrait of Velázquez, are not only persons but social ideas containing lots of variant kinds.

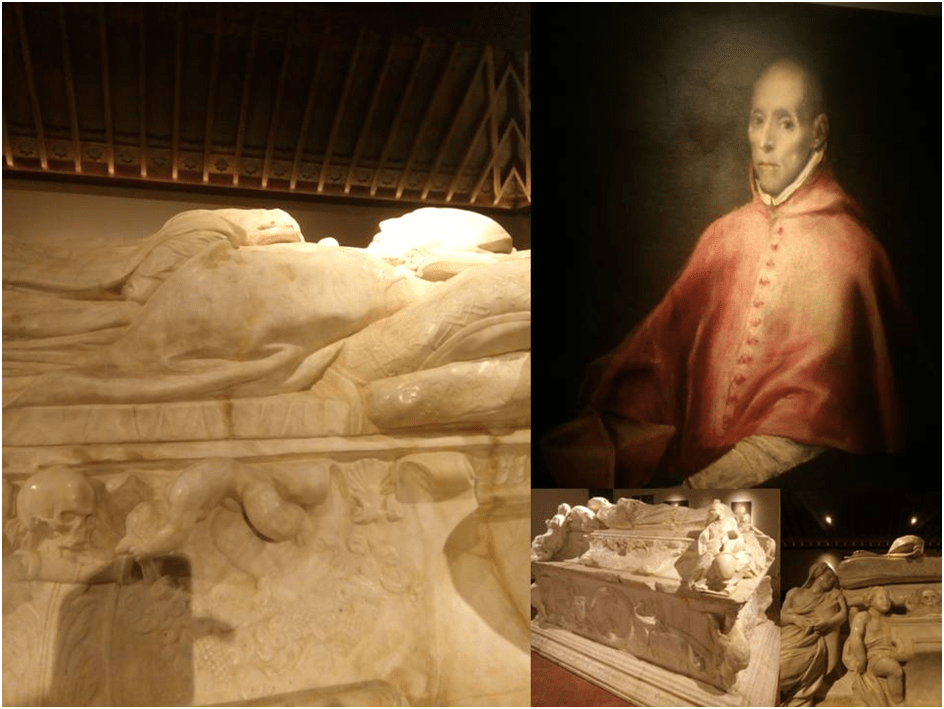

We can start with that Catholic Church clerical men. Certain examples are hardly distinct from either kings or saint paintings and sculptural portraits in their idealisation to an idea. However, in the hands of genius, their idealised body often becomes a burden on the man trapped within as I would argue was visible (poor subjective me) in both, respectively a painting and supine tomb statue, by El Greco and Berruguete of Cardinal Tavera. Digital facsimiles of each are found in on the 4th floor of the Spanish Gallery (see below).

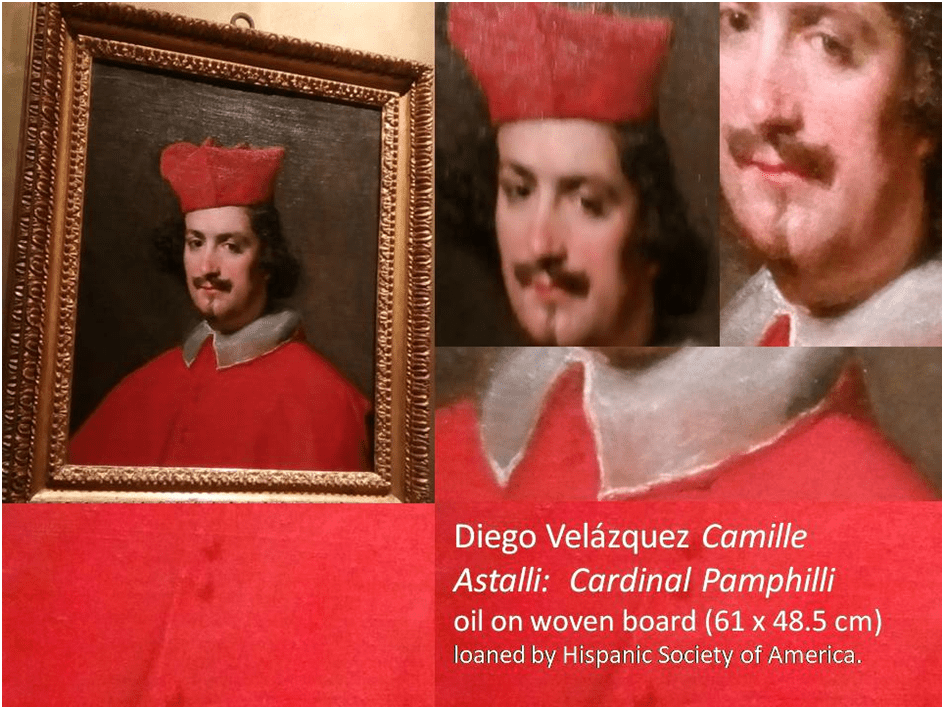

But ideal lives were not the sum of either contemporary understanding of the lives of many clerics in a world nor of the paintings produced: this is true even of Popes (as witnessed by Velázquez’s Innocent Xand the translations thereof by Francis Bacon in the twentieth century). But many of these lives were less grand and less individually magnificent. It is wonderful to see an example of a great piece by Velázquez on loan to the Spanish Gallery currently by the Hispanic Society of America, the portrait of a beautiful young man of jaunty and fluid morality Camille Astalli: Cardinal Pamphilli (painted probably between 1650 to 1651 according to Jonathan Brown shortly after the metamorphosis of Camille to the purple).

It is very difficult to even try and improve on Jonathan Brown’s description of the painting, which I offer below. From that description I extrapolate two things. First that, Velázquez initiated a move that perfected an understanding of the portrait of a psychological turn to portraiture that no longer made the two bodies of a person and their status, as we saw even with Coello’s Mariana of Austria, in some way as integrated – even if with contradictions – but makes the body and its personalised dynamics more central than the status and ideal conveyed by other aspects of appearance, setting and props. Secondly, the artist aims in the portrait to show his own skill and standing qua the making of innovative artistic process as much and perhaps more than the personality represented, although to some extent these aims are all of one piece since the artist’s skill begins to lie more in their perception of character and its submerged narratives of biography and career. Brown says that this portrait:

… has a wispy quality, the result of using pigments which barely cover the grainy surface. The effect is magical; the play of light and shadow is suggested by the careful control of the brush. The strokes are so sparingly applied that they can almost be counted, yet the image is complete and convincing. And the character of this vain, feckless man, who wears his biretta at a rakish angle (deliberately tilted to one side after having been painted as level), is nicely understated.[19]

Brown’s critical magnificence is shown here by his brilliant understanding of the significance of the pentimento (reference to which I have italicised) which showed that it was most probably the painter who controlled the interpretation of the sitter rather than some negotiated detail, and that that painter knew what he was dealing with in this worldly subject, though with a kind of love for his utter humanity. For Astalli’s career was one of feckless careerism. He was nephew of Innocent X and appointed, according to Brown, to regulate papal business in 1650, losing his status only three and a half years later as a for his ‘incompetence’ in that role.[20] Yet that Velázquez found this man beautiful and witty I have no doubt. The face communicates even in its lighted gaze upon the viewer. To appreciate his beauty in the splendid scarlet of his robes with the impressionistic finesse of its lace edging at the collar is to see social ideas not merely embodied but in a way in which the body takes control of the appearance and reinterprets it in very humanistic manner.

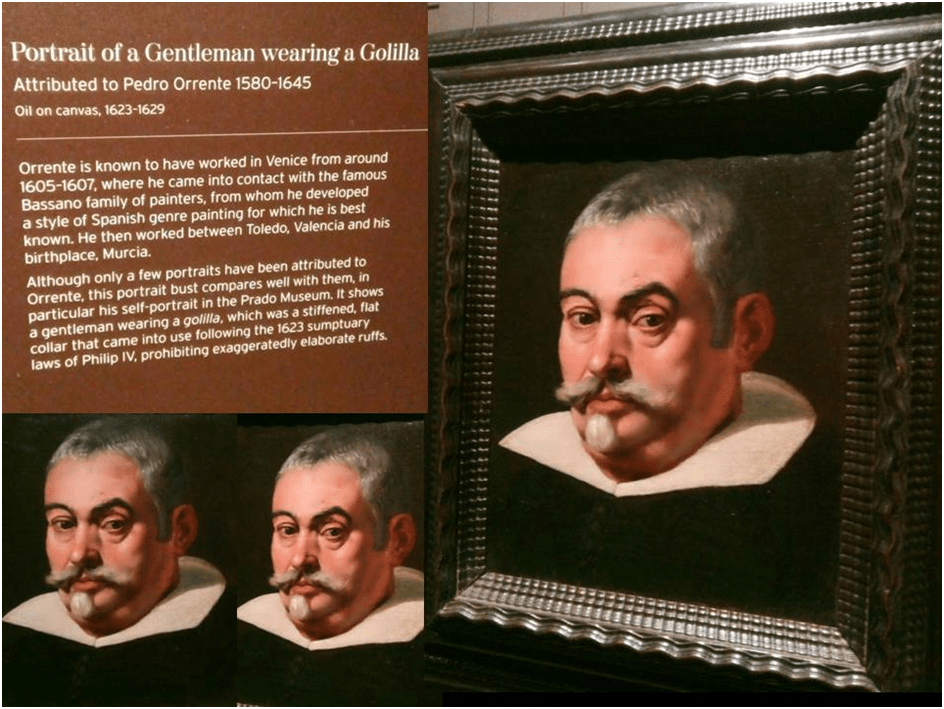

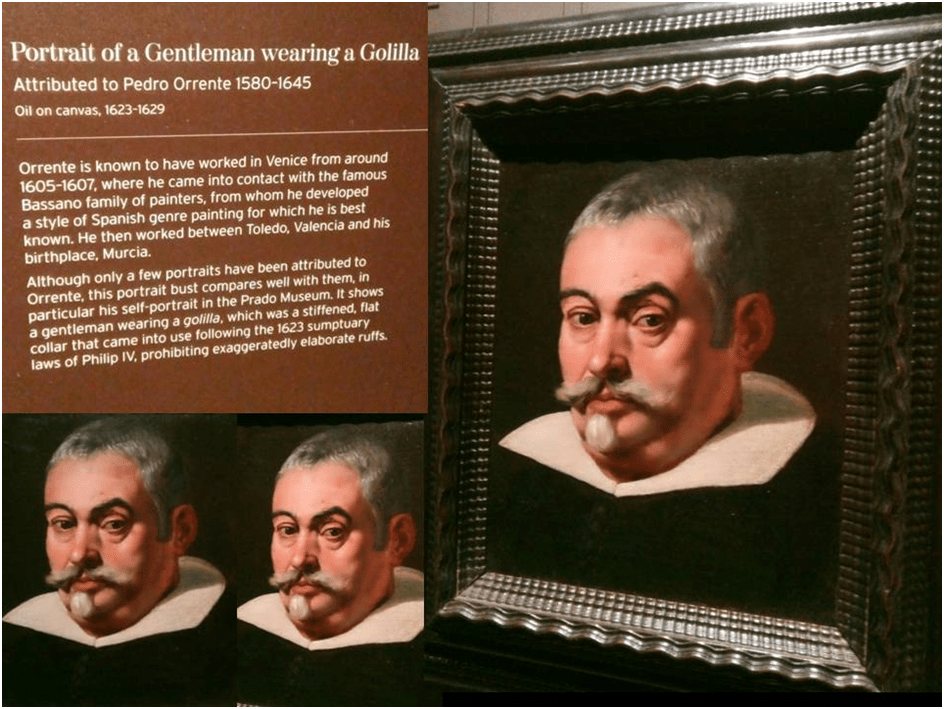

When the painting is merely of a Man, such as Pedro Orrente’s Man in a Golilla, this may be because we have lost the information of the sitter who may have commissioned it, but it may also be because the power of the state was beginning to pass into the hands of more common men, though the reality of this was still a long way away.

Moreover, the tradition Pedro Orrente imported back to Spain reflected a model of painting he learned with the Bassano family in Italy which involved the creation of genre scenes – reflecting ordinary life – its characters (and scenarios sometimes though not in the example I give below since the cutting of giant heads was not a common occurrence in seventeenth-century Spain – LOL) whilst anonymous young men in disrupted dress might have been. The trend in a more ‘modern’ Italian setting is clearly to the capture of character – akin to portraiture of course – of common men in common situations (however translated uncomfortably by the Biblical narratives they support). Here, following an Orrente drawing of David with the Head of Goliath is the Prado’s summary of this trend:

During his stay in Venice he must have absorbed not only the Bassanos’ approach to painting, but also their conception of it as a market-oriented activity. Fundamental, in that sense, was the treatment of religious subjects as genre scenes; lively series of bible episodes that invite the viewer to admire their variety and dynamism with a plethora of figures in the landscapes and a profusion of animals and everyday objects.[21]

For me, subjectively of course, this is the feel of the Gentleman in a Golilla. For the Golilla is a reduced ruff imported into Spanish wear for gentleman, according to the museum caption (see below for picture [again] of this) in 1623 by the sumptuary laws of Philip IV.

This portrait is rich in the character of an ‘ordinary’ man (anonymous except socially that is) of course but also points to a social narrative – those sumptuary laws which were perceptible themselves as a social experiment in typing by class in a world running with under-distributed riches amongst the few – now including non-aristocratic gentlemen.

The story of portraiture here is of course full of gaps – partly by my restrictions on material and partly because all small collections must (helpfully for viewers) skew the range by their selection (including contingencies of availability and ownership) of artworks. But to start with the wonderful collection in the Spanish Gallery is no bad thing.

My next blog I hope (no. 8 in this series) will be one on the art of Zurbarán, though having I am anticipating longer intervals between my Spanish art blogs. Nevertheless, I hope I see someone there when it is finally produced if ever.

All the best

Steve

[1] Javier Portús (2004: 19) ‘The Varied Fortunes of the Portrait in Spain’ Javier Portús (Ed.) The Spanish Portrait Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 16 – 67.

[2] See Shearer West (2004: chapters 1 & 2 respectively, 21 – 70) Portraiture: Oxford History of Art Oxford & New York, Oxford University Press.

[3] Vernon Hyde Minor (1999: 211 – 244) Baroque and Rococo: Art and Culture London, Laurence King Publishing.

[4] Ibid: 211 & 215-217.

[5] Javier Portús op.cit: 29f & for ‘theology of painting’, 32ff.

[6] Gabriele Finaldi (2004: 149) ‘Portrait and Reality: Ribalta, Zurbarán, Ribera’ in Javier Portús (Ed.) op.cit, 146 – 165.

[7] [7] Hugh Trevor-Roper (1976:32) Princes and Artists: Patronage and Ideology at four Hapsburg Courts 1517 – 1633 London, Thames & Hudson.

[8] Ibid: 34

[9] Ibid: 24

[10] Barbara Reynolds ‘Introduction’ (1975: 23) in Ludovico Ariosto (ed. Barbara Reynolds) Orlando Furioso: Part One London, Penguin.

[11] Ariosto Orlando Furioso Canto XVII. 74f.

[12] Jonathan Ruffer (2021: 36) The Spanish Gallery: A Guide to the Works of Art Bishop Auckland, The Auckland project

[13] https://biblehub.com/romans/16-20.htm

[14] Hugh Trevor-Roper op.cit: 56

[15] Sarah Schroth (2008: 83) ‘A New Style of Grandeur: Politics and Patronage at the Court of Philip III’ in Sarah Schroth & Ronni Baer (Eds.) op.cit.

[16] Hugh Trevor-Roper (1976:47ff) Princes and Artists: Patronage and Ideology at four Hapsburg Courts 1517 – 1633London, Thames & Hudson & Sarah Schroth (2008: 77 – 122) ‘A New Style of Grandeur: Politics and Patronage at the Court of Philip III’ in Sarah Schroth & Ronni Baer (Eds.) op.cit.

[17] Jonathan Brown (1986: 173) Velázquez: Painter and Courtier New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

[18] Ibid: 173f.

[19] Ibid: 200f. (my italics)

[20] Ibid: 200

[21] Wikipedia translated page on Orrente from the Prado Museum. Available at: https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/artist/orrente-pedro-de/28776a91-9aae-404f-b465-464f4b899986

One thought on “Javier Portús explains of a Prado exhibition that ‘some readers may be surprised to see some pictures that are not portraits in the obvious sense’ but that they are included as an ‘opportunity to reflect on the boundaries between portrait, reality and representation’. This blog insists that those boundaries are nearly always porous and need added to them the liminal cusp of boundaries of the portrait to paintings that evoke ‘description’ also of the imagined supernatural wherever it occurs – in religion and political ideology. It uses as its case studies examples of ‘portraits’ currently in the Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland”