Why plays must end as they will: ‘the Gods look down / expect the unexpected … end of story. Black. / End’.[1] Reflecting on the reading of plays before you see them! The case of Euripides’ Medea (a play I have read and seen in different versions many times). This blog focuses on the version (‘after Euripides’ in the author’s term) written in 2000 by Liz Lochhead which will be seen by us for the first time in Edinburgh performed by the National Theatre of Scotland at the 2022 Edinburgh International Festival on Saturday 20th August (see addendum for addition after seeing the play). The text is available as Liz Lochhead (after Euripides) [2000] Medea London, Nick Hern Books Limited (pictured).

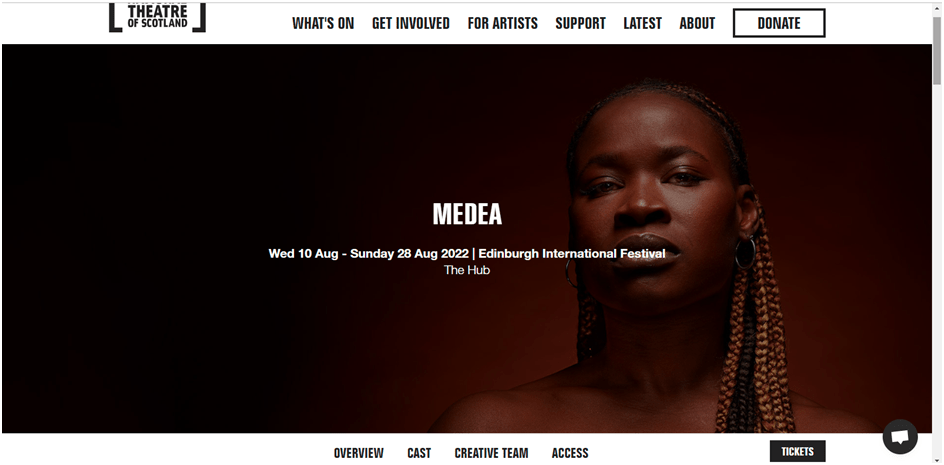

When I go to plays with other people, I’m often thought to be odd for wanting to know the text of the play, or a version thereof, before going. As for being ‘odd’, that remains the truth and I do agree that it is better to live through a story, and how that story is enacted and told for the first time, without overmuch expectation of the inevitable. As a born ‘catastrophiser’ however, I doubt I will ever get to this exciting position of discovery (LOL). Anyway, I thought that maybe I ought to reflect on why therefore, I feel I have to read even the ‘version’ of a play I know well already, before seeing it performed. Today I finished re-reading Lochhead’s version of the play. Why do I do this? After all, this is a play whose mythological subject was often retold (in many different versions from sources too that often existed in different versions) even in the fifth century BCE in theatres in Greece. Carmel McCallum-Barry makes the point that for the prolonged investigation of Medea’s infanticide in the play, and her escape from anything we might like to call ‘justice’ for her deed (helped even by a God), there is no known precedent in Attic drama. [2]

Of course seeing the play will be an introduction to something – its collaborative production by a team – that innovates even further on what I see in the text, which will, of course anyway be far from all there is to see and may include things that were not seeable for other readers. In watching the production of a play we are aware the literal onstage ‘production’ of meanings from the acted text by devices within the process of producing a play as a piece of theatre. They include variations caused by (I use a list from an earlier draft blog):

- the use of body, and bodies in concert – including the things bodies themselves produce such as voices, sounds, gestures, tones, differentials of gait, stage proxemics and variations of stance and visible ‘attitude’ to others;

- the whole series of settings of specific sections of the whole play, from stage ‘scenery’ (or its marked absence), and changes thereof by any number of means including lighting, other ‘artificial’ or natural effects, the form of the built stage itself, the theatre’s internal architecture, its place of theatre and context in time and so on, and, finally;

- the use of ‘properties’ and costume (including ‘historical and cultural period items’ in both of these) that interact with text or extended its meanings, such as a skull, pen and paper or wrapped gifts (so central to Medea).

The changes caused by these non-textual elements involved could be radical, such that the text is no longer able to dominate meaning in its own right. They may even demand changes in the text as it plays out in reheasal.

But for now let’s look at how the text has made an effect on me and created expectation of what I shall see that I can hopefully test in a post-production blog. For Lochhead was determined to make changes that emphasised her ‘perverse attraction’ to the play: ‘a woman driven by female desperation … to killing her children’ and her belief that the case made by the play was not ‘misogynistic’ but quite other. She hints that her attraction was heightened by the possibility that Euripides fascination with the role came from the possible experience of Euripides playing a role he wrote for himself in drag. [3] The delight she finds in the play then is in part one about queering expectations of sex/gender roles – one she reinforces by showing that her desire to find modern Scottish society ‘truly tolerant’ has been shaken by the ‘furore over the abolition of Clause 28’. That furore does not suggest, she goes on to say that ‘smug and conventional attitudes of thinking’ that Euripides identified in his fictional Corinthian social setting (and perhaps his real Athenian one) in terms of ‘unthinking superiority to foreigners and women’ is confined to Classical Greece. Those attitudes of an Ancient society seem ‘unfortunately not totally unrecognisable, quaint or antique to me as I survey mine two and a half thousand years later’.[4]

Now that that furore is now (hopefully) consigned to history, I wonder if this production will take up the equal furore of that part of current Scottish society that is resisting the human rights of trans people as a bold devolved government tries to bring them into being. I hope so. For Lochhead’s play is based on a decision that changes the play in lots of ways, not least in the indications in the text of how the speeches of the main roles and Chorus needs to be spoken in terms of its identifiable ‘tongues’:

… it struck me that conventional way of doing Medea in Scotland until very recently would have been to have Medea’s own language Scots and the, to her, alien Corinthians she lived under speaking, as powerful ‘civilised’ Greeks, patrician English. That it did not occur to me to do other than give the dominant mainstream society a Scots tongue and Medea a foreigner-speaking-English refugee voice must speak of a genuine in-the-bone increased cultural confidence here.[5]

And we need to recognise that an ‘increased cultural confidence’ in Scotland must include the ability to question its own norms and expectations, even perhaps those about the nature of what is foreign to Scots in Englishness. For this is a play about how hegemonic values are produced from the exclusion and/or marginalisation of the ‘alien’ and ‘Other’ to the expected norm. Edith Hall, for instance, claims the reasons that Euripides’ play is so attractive to ‘every community in the global village’: in part at least, the play endures through the historic and cultural variations of both space and time is because of ‘its staging of dialogues between individuals of different ethnicities’. But this cannot be the sole reason. Cultural conflict across boundaries is a subject that ensures that the pay ‘asks more metaphysical questions than it answers’. What Hall calls the ‘metaphysical openness’ of the play is what allows its revision between languages that differ in time and across space. At this point Hall’s analysis ends but should not do – for it is precisely because the play dramatises metaphysical questions of ‘premeditation, provocation and diminished responsibility’ across various socio-cultural frameworks in which different predominant psychological and ethical priorities are stressed. That no one set of priorities prevails makes the play ‘open’ and unresolved with regard to problems of social living, such as family, identity, ownership and rights of self-definition.[6]

I hope that last paragraph explains why Trans rights might be central to a relevant modern production of Medea because such rights are currently being crushed in the failure to communicate between constructions of the interests of different socio-cultural and socio-psychological groupings and their voices. And it is trans voices which are currently being excluded – especially in the language of the ‘patrician English’, such as is spoken in The Guardian, even when it speaks under labels like radical feminism or radical lesbianism or exclusive alliances (whose very raison d’être is exclusion such as in the LGB Alliance). But this is yet to be seen. Certainly casting would play a significant part although there would be no reason to necessarily have a male play Medea herself, as would have the definite case in Attic Greece in the fifth-century (just as in Shakespeare’s Globe). Such casting must have created a great play of ideas when for instance Jason says to the audience, a Chorus of ‘women’ (played of course by military men in training), and Medea:

I wish there was a way to get us sons

without women the world would be a lovely place.[7]

Lest we think this is Lochhead queering the pitch, remember it is, as other speeches are not, as near a free translation of the gist of Euripides’ (a literal translation is in the footnote):

… Χρῆν νàρ ἄλλοθέν ποθεν βροτοὐς

παι̂δας τεκνοὐςθαι, θη̂λυ δ’ ούκ εἷναι γένος

χοὔτως δ’ ἂν οὐκ ἦν οὐδἐν ἀνθρώποις κακόν.[8]

In a modern context, this can be drained even of misogyny since there is more than one ‘way’ in modernity for men to get sons – though not of course without the free involvement of a woman. The issue historically is that women have not been free to opt in or out of a role in this process being bound by men, and, as Lochhead’s Medea herself asserts being constructed by men in their form as bound to the needs of the latter by heteronormative sex (reproductive or otherwise). Here is how she puts it (and it is in a radical manner):

it’s true I’ve not been a woman’s woman

I can say

I was never a woman at all until I met a man!

maiden Medea my father’s daughter was a creature

who did not know she was born she knew such

sweet freedom!

if it is a struggle in a bed or behind a bush engenders us

then it’s when we fall in love that genders us

….

oh yes wartime

and they’ll die for us!

well I’d three times sooner fight a war

than suffer childbirth once.[9]

This is so rich( and pretty near the meaning in Euripides again) because it plays a game with the contingencies of biology and their insertion into a socially gendered power hierarchy that constructs women as bound rather than in the ‘sweet freedom’ of childhood. What is not in the Euripides text is the play on ‘engenders’ and ‘genders’. This play on word etymologies and semantics opens up a theme based on the social construction of gender that potentially argues that biology differentiates roles in procreation but not the actuality of sex/gender which is always culturally produced once it takes on meanings in the social and political world. The Greek by the way, let me repeat, is no less radical. Mossman translates it thus:

we, who must first buy a husband for an extravagant sum of money and take a master for our bodies; …. They say we live a life without danger in the house while they fight with the spear, but they think wrongly; I would rather stand in the battle-line three times than give birth once.[10]

The reference to the reality of hoplite formation (stand in the battle-line) moreover here gives direct comparison between mechanisms of danger and security in the comparison of male and female tasks because the hoplite was formed to create a secure basis for warfare. It emphasises to me that such formations are social constructions, like the belief that women’s place in society was made secure by men alone.

Now Lochhead allows us to play games not only with gender construction and the power games that script its social operations but also the construction of ethnicity, race, class, age and other individual differences. Lochhead transforms Euripides original team of male soldiers, who would have played the Chorus of Corinthian women in the Attic theatre, into a ‘CHORUS OF WOMEN of all times, all ages, classes and professions’, and whom remain invisible to men of power, even Scottish men of power, such as KREON.[11]

Enter KREON, with the modest personal retinue of a very powerful man. His voice is strongly Scots. … In common with all the other characters except MEDEA, he is blind and deaf to the CHORUS.[12]

And Kreon can be thus blind and deaf precisely because the difference between himself and the chorus is that they lack the kind of relative power claimed as a natural right and possession by all men (‘I make the laws and execute them’) and who are ‘feart’ of people they have ‘heard () dared to threaten us’. [13] It’s noteworthy that men act to defend their power and security not on any actual challenge they hear or observe but only ones that they construct ideologically through what is both said and heard by those already benefitting from a patriarchal distribution of power (largely men) or too afraid themselves to challenge it – like the NURSE and the ‘grunt’ (Medea’s word) who plays Medea’s messenger as well as paidagogos for her children. For the marginalised characters that queer the meanings of this play are those excluded from power in all those categories intersecting with each other, including that of female gender, whether as of lower class and status, alien or immigrant foreignness from the local norm (even norms within a Greek state using the same languages as the marginalised othered state), race, culture, ethnicity or neurodivergence, especially in the neural regulation of emotion, including the tendency to wail, cry or ‘greet’ as sung about in the choric lyric that precedes Medea’s first entry onto the stage.

That cry

We have heard it

From our sisters mothers from ourselves

That cry

We did not know we knew how to cry out

Could not help but cry[14]

Those who prefer norms, like servants convinced of their inability to fight back (the NURSE is my example), are, as are Kreon with Medea, ‘in terror even to approach’ those seen as other and dangerous because these alien others are not understood.[15] Although sometimes young girls, like Glauke, also support norms because they do not ‘entirely grasp the situation’ that their role in male marriage-and-inheritance games creates for them. That role does indeed constitute history but eradicates every shred of ‘her-story’: it is a tale of constant powerful oppression pretending to be merely the nature of things (or ‘Physics’ laws’) but actually a justification of ‘faithless’ behaviour; which to any reasonable observer would look ‘insane’.[16] No wonder she accuses Medea of being one who has learned, because she lives ‘in the past’, to overthink female oppression and thus become rebellious to men she still believes will secure her happiness forever, just because they make her happy now:

I am a civilised person a Greek

these things happen we must

for the sake of the children if for no one else

make the best of things.[17]

This is why Lochhead inserts the scenes of Medea in conversation with the young GLAUKE – KREON’S DAUGHTER – on purpose to show that the fact that some women support their own oppression is because they are beguiled by clichés from patriarchal ideology like ‘for the sake of the children if for no one else’ and the claims of ‘civilisation’ (however uncivil it turns out to be). For throughout this conversation, as between Medea and JASON, the word ‘our’ and ‘my’ continually emphasise that children are seen primarily in social and cultural capitalism as a ‘possession’ not as a person with rights to self-determination, even perhaps by Medea. They are, as Glauke says things a woman bears so that they can ‘give him’ …’more babies’, as if a gift.[18] This is why Euripides combines the idea of gift-giving in this play with the notion of children as transferable property. They are predominantly to women in the play ‘his children’ in this kind of transfer. They only way that they might stop being so, Medea concludes in the original Greek play, is by their murder and female-led veneration once dead (although this is too Greek a perception and Lochhead cuts it from her version of the play together with Helios, the God of the Sun, who redeems Medea in his chariot).

… I will bury them with this hand, bringing them to the precinct of the goddess Hera Akraia, so that none of my enemies will do them violence and tear down their tombs, …[19]

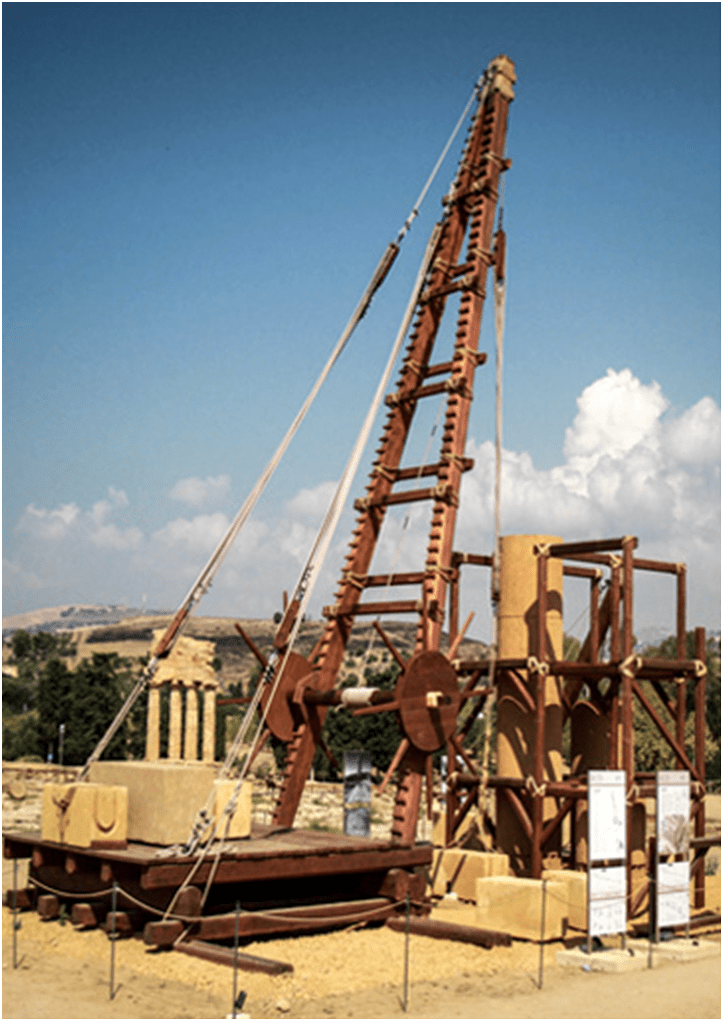

The reason Lochhead abandons Helios’ chariot as a means of rescuing Medea is not only that she is ‘dispensing with the “deus ex machina” ending’ (as so despised in this play in Aristotle’s Poetics).[20] but also because of that philosopher’s precise reasoning in that work. Edith Hall explains that Aristotle hated the ‘contrivance’ because it gave Medea the sort of omniscience’ that ‘belongs not to humans but the gods’.[21] Lochhead nearly uses the same terminology: ‘My Medea is not supernatural, not an immortal, but is all too human’.[22] Only a fool like the ‘grunt’ MANSERVANT says:

Run run you bitch of hell

you really did it and you’ve done for us as well

a ship a chariot go [23]

For Medea, as for us in the audience, the last words to be understand are ‘end of story’ and that end is not escape from male oppression but facing the truth that men father not a beginning but something like the Black and End which are visually the denouement of this version of the play: ‘the father you had / end of story’. Jason in this version is grotesque in Lochhead because he imagines his downfall as the moment he ‘turned to [Medea] in the night’ and when ‘he felt my seed spurt to [her] foul womb’. [24] For wombs are foul to men who only see them as birthing ‘my children’ as their continua to the future not autonomous beings in control of their own destiny in the last analysis. Such men feel that their touch is so important to anyone who feels it that they can deny even ‘to touch you / even with my sword’s tip’ but Medea has found a place where, ‘nothing you can do to me can touch me now’, fee even from ‘memory of [his] vile touch’.[25]

What this version does is attempt to find space for difference from the norm – for everything that we might call ‘queer’ and ‘other’, including the refugee and the alien, which is, in Edith Hall’s terms (in another publication) which is usually associated with magic, the intermediary supernatural and the wild and unboundedly free from socio-psychological constraint. It makes clear that, however foul the idea of child-murder, such acts are facts hidden under the cloak of civilised language in a civilised culture by something little better than cliché: ‘I’ve done everything I could for you the kids / but you fling it all back in my face’.[26]

Against these claims Medea, and to a lesser extent the CHORUS, pit their cleverness. Female cleverness is a thing normative societies hate more than anything – hence the Medea’s statement that ‘clever men are envied / and despised … but a clever woman / fie it is to fly against the face of nature’.[27] At the base though even of that prejudice of bourgeois shallow thinking is the fear of those who try to explain this issue. Hence shallow inadequacy can hide behind the normative label (like Brexit for instance):

No one loves a foreigner

Everyone despises anyone the least bit different

…

‘why can’t she be a bit more like us?’

Say you Greeks who bitch about other Greeks

For not being Greeks from Corinth![28]

And such limited thinking gets weaponised in supposed self-protection, although sometimes masked as ‘protecting’ those ‘othered’ from their own unconventional and hence dangerous thinking. Nowhere is this clearer than in terms of class and status in a hierarchical society, where even the lowly praise the benefits of them lacking power and the respect of others. The Nurse illustrates this beautifully:

Is it no true the grand and horrid

Passions of the high and mighty

Rule them more cruelly

Than they the rulers rule us humble folk?

A quiet life we’re thank Gods too dull

To draw doon the vengeance of the

Ayeways angry Gods that look down and ayeways punish

Them who think theirsels somebody[29]

For what comes of this is the absolute truth that power is seen (whether human or divine) as cruel and uncaring and only protective in ideology in class-bound societies, and this truth (though it helps the Nurse not one jot so low is her status) is a specifically strong culture that is definitively Scottish. Because does not this speech, and also one of Medea’s to Glauke where she praises ‘empathy’ and ‘imagination’ to ‘put everything into perspective’ and ‘see it from the point of view of the / other players in the drama’, actually invoke that archetypal Scottish poem satirising the ‘high and mighty’, Robert Burns’ To A Louse: On Seeing One an A Lady’s Bonnet.

O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us

To see oursels as others see us!

It wad frae monie a blunder free us

An’ foolish notion:

In fact Medea says to Glauke that, despite every appearance, it was she that ‘made that man’ with her cleverness and strategies just as the working class make power possible for those who rule over them not the advice of their fathers with their work: ‘the toffs in Corinth / the ruling classes leaders / or a leader’s wife first lady’.[30] Medea, of course, and this is the extent of the extremity of her logic, reduces Glauke when she is ‘taen on wi hersel’ in borrowed finery made by Medea into disintegrating flesh, breath and viscera noticeable as merely mortal even to a ‘serving lass’.[31]

And yet the entitled by binary division are inclined to deny trans people the right to self-determination in Scotland. Medea plays up to their fancies telling her MANSERVANT that yes, the task she has given him, ‘it’s no job for a man!’, but accepts provided it can be agreed that ‘I’m no much of a man for describing frocks’. Nevertheless when he returns he is soon inveigled into ‘describing frocks’ with the relish of Jennie Bond at a court event. Perhaps more so because you feel him trying on the clothes in his reporting imagination:

… gold on gold on tap of her hair

when she pulled oot that soft silk shawl

there was a sigh went up at its shimmer

and she slipped into it

smoothing it over her breists and shooders

….[32]

And so on. I do hope my prediction is borne out. For no play can stand still as history moves on and the heteronormative like other norms picks new targets to marginalise.

So I’ll be back after August with an account of what I actually see in the production proper. Why not see it yourself. Bye for now.

Steve

ADDEDNDUM AFTER SEEING THE PLAY:

This was a most magnificent production. I think it did indeed allow some of the subtleties I strain to find in my proses in the text above to be seen and felt directly – viscerally I would say. But, as in any great and greatly acted production, they addressed you as in life. Staged in a great hall on a stage that bisected the auditorium, with entrances and exits from the same door at which the audience entered and a dark hole at the back of the stage behind which horrors can be imagines, action also took place in the auditorium, especially the interventions of the Chorus, such as their relationship as mediators for that audience was more than clear. As a production it was greater than anything anyone could say about the play because it was the experience I talk about above not just talk (as my thoughts remain). The bearing of the gifts by the children that will kill Medea’s enemies was so moving I can barely remember it in my words but pictures return to me. No performance was less than superb but that of Medea exemplary. I could barely imagine now anyone else playing the part, though I saw the wonderful late Helen McCrory in one version. My great friend Justin described it as ‘awesome’ but also brilliantly comic in its exposure of sex/gender/procreation/sex-as-pleasure issues. It was all these things. I bow to that last word.

[1] Liz Lochhead (after Euripides) [2000: 47] Medea London, Nick Hern Books Limited

[2] Carmel McCallum-Barry (2014: 33) ‘Medea before and after Euripides’ in David Studdart (Ed.) Looking at Medea: Essays and a translation if Euripides’ tragedy London, Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, 23 – 34.

[3] Lochhead op.cit: page v-vi (from Play’s Foreword)

[4] Ibid: vi

[5] Ibid: vi

[6] See Edith Hall (2014: 140f) ‘Divine and Human in Euripides’ Medea’ in David Studdart (Ed.) op.cit, 139 – 155

[7] Lochhead op.cit: 20

[8] Euripides (ed. & trans by Judith Mossman) [2011: 132 lls 573ff.) Medea Oxford, Aris & Philips, Oxbow Books. Translated by Mossman as ‘Mortal men should produce children from somewhere else, and there ought not to be a female race; then there would be no misfortune for men.’

[9] Lochhead op.cit: 9f.

[10] Euripides (ed. Mossman) op.cit: 105.

[11] Lochhead op.cit: 7

[12] Ibid: 11

[13] Ibid: 11

[14] Ibid: 9

[15] Ibid: 8

[16] Ibid: 16 CHORIC SONG

[17] Ibid: 26

[18] Ibid: 26

[19] Judith Mossman (ed.) op.cit: 203, 205 (lls 1378 – 1380 in the Greek)

[20] Lochhead op.cit: vi

[21] Edith Hall op. cit: 139f.

[22] Lochhead op.cit: vi

[23] Ibid: 39

[24] Ibid: 46f.

[25] Ibid: 45 & 18 respectively

[26] Ibid: 21

[27] Ibid: 12

[28] Ibid: 9

[29] Ibid: 6f.

[30] Ibid: 32

[31] Ibid; 40f.

[32] Ibid: 40

One thought on “Why plays must end as they will: ‘the Gods look down / expect the unexpected … end of story. Black. / End’. Reflecting on the reading of plays before you see them! The case of Euripides’ ‘Medea’ (a play I have read and seen in different versions many times). This blog focuses on the version (‘after Euripides’ in the author’s term) written in 2000 by Liz Lochhead which will be seen by us for the first time in Edinburgh performed by the National Theatre of Scotland at the 2022 Edinburgh International Festival on Saturday 20th August. The text is available as Liz Lochhead (after Euripides) [2000] Medea”