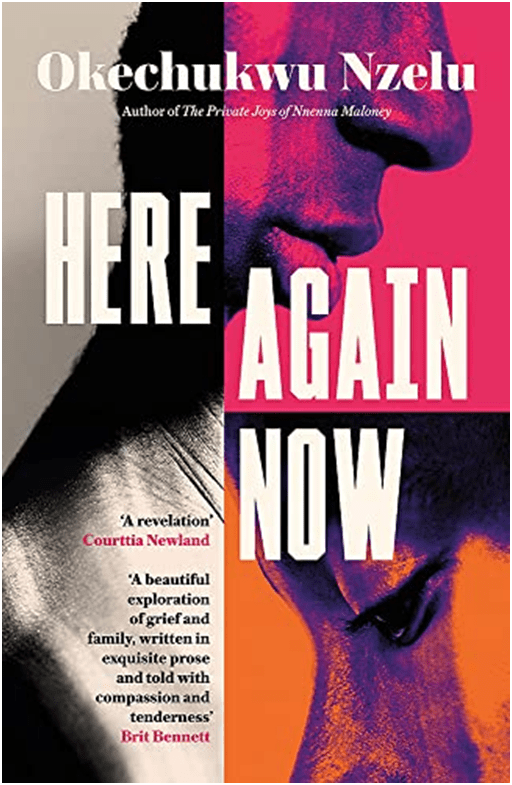

‘Could he live with the man forever, and be his – what? … There was no language for what should happen next’.[1] ‘What were they, after all?’[2] This blog reflects on a novel that, I’d assert, queers even the gay literature it advances upon and goes well beyond: Okechukwu Nzelu (2022) Here Again Now London, Dialogue Books.

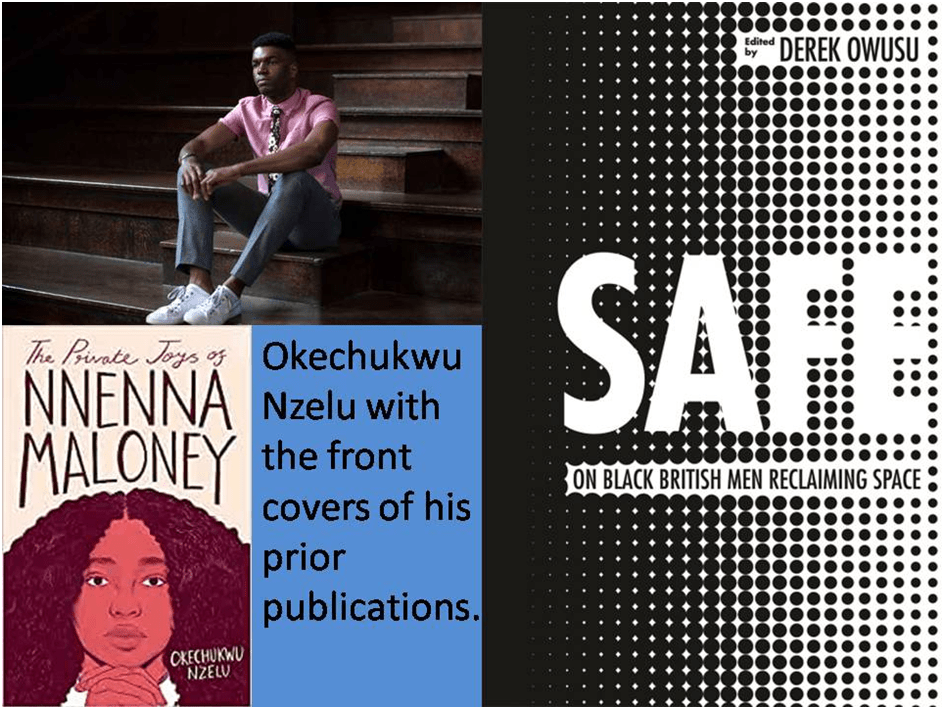

As I look back on my earlier blog on Okechukwu Nzelu’s first novel (follow link for that blog) I recognise from that, admittedly much simpler and lighter novel, The Private Joys of Nnenna Maloney (2019,) some resonance of preoccupation between them. One such is the contrast between messy and the clean and tidy (and the continuum between them) that make up our expectations of what our relationships should be, whether to self or others. Another is a connected concern with what ‘language’ can name and what it cannot and with what larger frameworks of human experience it can describe and what it cannot. A third also dealt with in a beautiful essay by the author about which I also have blogged, concerns the tension between black and white queer experiences – that covered in the messy hard-to-name interactions between this parts from intersectional facts of life as lived in unequal societies.

The latter theme is less prominent here but cannot be avoided. It is in the inadequacies that are hardly explored but hinted at in the secret relationship between one of the key characters, Achike, and his powerful theatrical agent, Julian Trent. Julian, speaking from an unchallenged position of white privilege knows that the world controlled by white filmmakers ‘was waking up to the possibility of young black men playing a wider range of roles than ever before’ but lands Achike first with ‘minor roles … a period slave drama’ and ‘a tragic family epic’. His next role though, Julian promises: “you’ll like …’.[3] Julian can also talk later glibly and with some tone of patronage about it being ‘hard’ for young men like Achike and his friend, Ekene, ‘being gay in the black community’, as if that community were the primary problem for black queer men rather than a colour-blind white hegemonic one that constrains it. And the problem with Julian too is that he uses the age differential between himself and both young men to take on the role of a ‘father figure’.[4] Such a role is based on his greater power in terms of privileges accorded to white people AND to high status elders, rather than that of an equity that might naively be expected of a ‘couple’. Indeed we only learn, or have confirmed for the more suspicious of the motives of older white gay men, that he has a ‘couple’ relationship with Achike when Ekene does late in the novel.[5]

It is role-playing of parent-child kind in romantic and sexual relationships, between multiple varieties of participants and mixtures of participants that is the thematic centre of this novel. Thus immediately after, and very early in the novel, Julian is identified as patently a ‘father figure’, we are introduced to the curmudgeonly views of Achike’s ‘real father’, Chibuike, who ‘criticised Achike for letting white Hollywood subsume him into itself’. We know as we read on that Chibuike has a valid point here, however nuanced out take on it might be. And, pushed by Julian he must play the role of a Nigerian male as others want to see it, that is in a manner that is decidedly heteronormative in relation to his more confident (perhaps – the text does not allow us to be sure) co-star, Dacey Douglas:

It was upon him to be the man now. The director was watching, and she wanted to see what love could look like. Achike tried to imagine how he might love Dacey in another life. He might be a different man, then, and tower over a woman, and not long for a man to hold him.[6]

In this novel, ‘what love could look like’, whether the role is in a film or in what we call ‘real life’, is deeply scrutinised and answers given by any of the characters or the narrator to what we see in seeing ‘love’ or its facsimile entirely unsatisfactory. Moreover, the languages (including those that are strictly only silently embodied) you might use to name, perform or describe it are also open to questions and herein lies the novel’s queer radicalism. This is why I choose those particular citations in my title because both are about entering into a relationship, or more truly hovering on the threshold thereof, without ‘name’, plot or scripted language. In one sense this recalls Wilde’s ‘love that dare not speak its name’ but it is much more profound since various homonormativities are easily invoked in this novel: they just cannot be lived by this cast in this place or at this time. The most chillingly described herein are those where the roles of man and boy-child, independent adult and persons in familial bonds, play through relationships supposed as ‘adult’ and between different families not within the same real or imagined one, where memory and desire mix in an inbuilt resistance of will to either flesh or the word willing itself to become and inhabit flesh. Here a long quotation is needed that describes a ‘pretend’ father (Chibuike to Ekene) but definitively older male responds to a boy whom he ought to treat like a son whether he be one or not, but who doesn’t, seeing in such a response too many unnameable other possibilities in the love between males and between elders and the very young:

… it was true that Ekene had seemed to disappear for a while that summer, and that something bright and gentle in him never returned. And that, one day, something dark and sullen took its place. …

Worse than this was Chibuike, seeing the question in Ekene’s eyes but afraid that his answer would be wrong. The thoughts, the love unexpressed, sat patiently undefined, like stars behind smog. … How could he find his way when there was no path? It felt as though no man had ever said those words before. If there were a name for Ekene’s place with him, could he be the first to say it? How could he speak a world into being? How could he invent a language for love?[7]

Many people will read this passage smugly, confident that it hides merely a man’s inability to think outside the heteronormative in the manner of an unreliable implied focus of novelistic consciousness. But there is more here and it remains problematic to the end. True, Chibuike clearly is forced to question his beliefs about masculinity that that there could only be ‘distance and sex between men’ and that there had better be therefore just distance.[8] The taboo on male closeness is clearly shattered by events in the novel. However, there is no degree of clarity in how that proximity will be or is performed going forward into a shared or divided life by the two central male characters by the end of the novel. It is clear to all that though men ‘did not do such things’. [9] They in actually can do AND do them and that the range of prohibited behaviour can narrow as well as widen despite the ‘foreignness of what must be done’.[10] The novel leaves us with a puzzle in the close of its penultimate section or part (with only one visibly short part of it left) with the words:

Yes, it was an impossible thing they might do now.

They did it.[11]

But what they did is never named or described. Conventional thinkers and readers will rush to outline all the things this thing could not be. But the queerness of the novel lies in the fact that such a list is by this time impossible to draw up. What do each of us want to exclude from this interaction of elder and younger and between those who owe both each other and the human who created unknowingly their mutual connection? We want a clean and clear answer but get none.

And here the muddle that is human relationships lived beyond theorisations of norms comes into its own. Achike is a beautiful man in body and in his public behaviour. We are to know later that this may be a matter of appearance only. We know ‘how tidy Achike’s bathroom was’, with everything left ‘in the same pace, just in case’. His hand towel at moments of crisis is not only available but ‘clean’.[12] Ekene is much more like Nnenna in the earlier novel and even as a boy Achike finds Ekene’s clothes ‘scruffy and unironed’ because ‘he doesn’t know how to look after things’.[13] Even as the novel begins to close Ekene ‘wanted to feel clean, and to understand himself’ and goes to church with this aim in mind. But in actuality: ‘He was’ (still) ‘messy, and difficult’.[14] And thus is life I’d say – queered by muddle and mess just as E.M. Forster would have seen it, barely able to keep its cuffs clean. Neither art nor love, between any persons, is what we “just wanted it to be …’, in Achike’s words. All we might do is gaze and ‘trace the delicate lines’ on our loved one’s face and know simultaneously: ‘How wonderful that felt, like observing art’.[15]

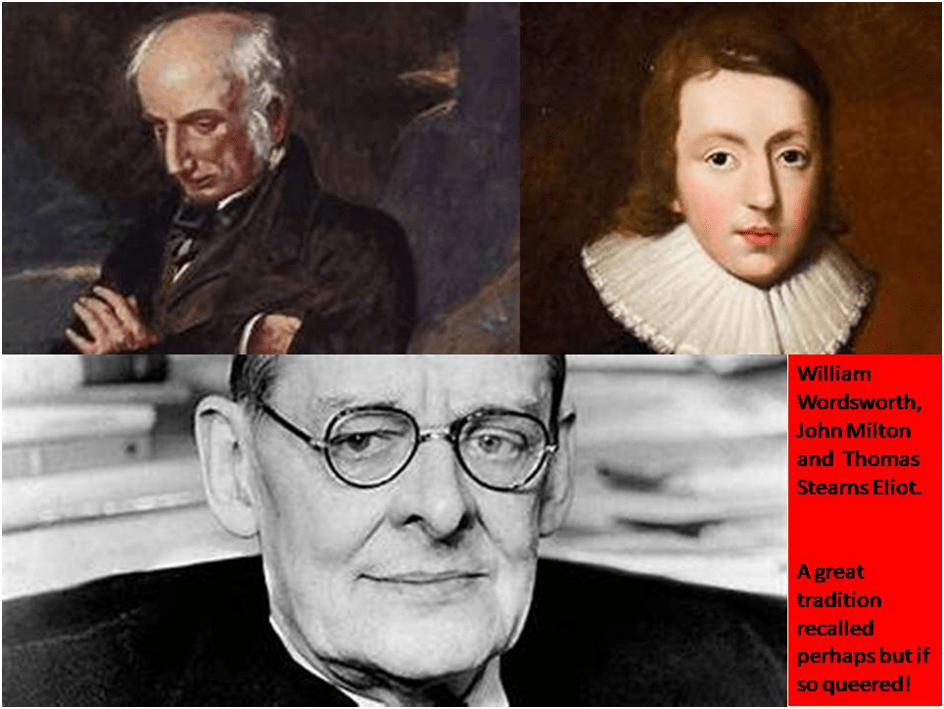

For this is the standard Nzelu sets himself – art that redeems somewhat the mess that lives and relationships remain. And thus the standard is the artistic tradition queered for use by a novelist with new aims in adapting them. In a novel as full of suppressed echoes of other works (suppressed because we don’t NEED to know they are there), various art works are invoked and I will have missed many such echoes. The most obvious (a work I love) I feel unable to say much about yet until I have read the novel many more times, since it is Tennyson’s In Memoriam, which provides the epigram of each part of the novel with a lyric from that poem. So I leave that one alone, much to my chagrin and diminished hubris (LOL) – since I pride myself on knowing that poem so well.

But of the ones I have noticed think of the central use of Wordsworth’s ‘My Heart Leaps Up’:

The Child is father of the Man;

And I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.[16]

The inversion of child / man and father / son relationships here are essential to echoes in the novel and its plot, so much so that one illustration will suffice:

But Chibuike needed care. He needed the tenderness of a father, or he would slip back into the man he was without it. Ekene didn’t want that. But how could he be a father and a child?[17]

Other echoes are much more subtle. One is so much so that I may hear it more than it is there but I deeply want it to be for it supports my view (an unnecessary one for anyone else to need to hold) the Nzelu’s position in the role of the great art of that past is a radical and revisionist version one of Eliot’s in Tradition and the Individual Talent, as in this passage where he sets a standard for the use of the past that a great artist in the offing like Nzelu can aspire queerly towards, subverting norms and ‘order’ set up by past paradigms enshrined in monuments of the past and altering them – queering them perhaps:

The existing monuments form an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new (the really new) work of art among them. The existing order is complete before the new work arrives; for order to persist after the supervention of novelty, the whole existing order must be, if ever so slightly, altered; and so the relations, proportions, values of each work of art toward the whole are readjusted; and this is conformity between the old and the new. Whoever has approved this idea of order, of the form of European, of English literature will not find it preposterous that the past should be altered by the present as much as the present is directed by the past. And the poet who is aware of this will be aware of great difficulties and responsibilities.[18]

Where do I find this? First I find it in an echo of words and rhythm from early Eliot – from The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock in fact. Here is Eliot:

For I have known them all already, known them all:

Have known the evenings, mornings, afternoons,

I have measured out my life with coffee spoons;

I know the voices dying with a dying fall

Beneath the music from a farther room.

So how should I presume? [19]

(my italics)

Music heard from a distance hums through Here Again Now but here is the bit that recalls these lines to me: ‘For some time …, Achike had lived in transit, measuring out his life in journeys’.[20] It’s momentary the echo but for me decisive. It need not be though for the novel to be enjoyed. It matters more to me in that later in the same sequence of description of a funeral in a church (one page later), there is this, as Chibuike listens to old ritual guiding him, as it were in the priest’s ‘old, steady hand’, but significantly, in a world revised, a female priest (tradition, that is, meeting up with individual talent in forms previously unavailable in a woman’s not a man’s body):

The woman read on, and ordered things. There were readings and hymns, and silence, and lit candles. This was it. It was ritual he’d wanted, the going where others had been.[21]

Is not this an echo of Eliot’s final phase of searching places where others have sought meaning, often in ritual – his new talent absorbing the order of old ritual as a solution to the passage of time and mortality in a form of music in The Four Quartets. Here I cannot locate the words in a precise echo but I feel it to be so – a subjectivism of little use to others I agree. Whether or not Eliot is echoed, the meaning of his literary career feels absorbed in a new way here by Nzelu. It is a new way that still requires the language of religion – of the experience of redemption from a kind of perdition that needs more exploration in the novel. It is a place I do not want to go here but it rings through the novel in references to ‘light’, as where, for instance Chibuike remembering his youth finds a job because he is needed ‘to fix this door hinge, change that light fixture’: ‘he welcomed that, feeling redemption in the difficulty. It had been so long since he had been useful to anyone’.[22]

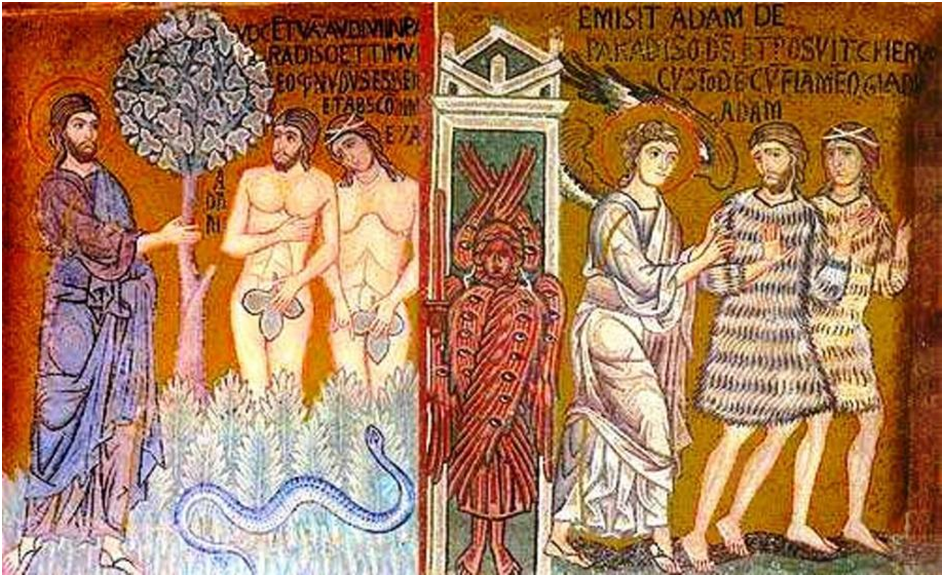

A more clearly demonstrable echo is of Milton. For instance Ekene’s frequent dreams of Achike in the latter’s long absences on the set of films is almost a parody of the situation of Eve in Milton’s Paradise Lost Book V, wherein Achike is both Adam waking Eve to his beautiful glory but also perhaps Satan whispering in her ear and ‘feeding (her) a dream’: ‘Ekene woke to the sound of him humming a new piece of his own making, woke to the sound of some creation pouring into his ear, as though Achike were feeding him a dream’.[23] The reference to ‘creation’ discovered by God’s created is fixative here. More evocative of this primal creation of heterosexual love and marriage in a queer male couple is this, for the rhythm and words are clearly there to see if a reader is aware of them in the description of the two young boys meeting first at school: ‘And in Achike’s mind, they never did unclasp: in his mind, they are walking hand in hand into this strange, too-bright world in which they must make their solitary way’.[24] Let’s fix that by quoting Milton in this text rather than a footnote:

Som (sic.) natural tears they drop’d, but wip’d them soon; [ 645 ]

The World was all before them, where to choose

Thir (sic.) place of rest, and Providence thir guide:

They hand in hand with wandring (sic.) steps and slow,

Through Eden took thir solitarie (sic.) way.[25]

The context of exclusion from a paradise prompting the new union of a couple is precisely there. This is a lonely world otherwise, both texts insist. Our choice of companions is, and perhaps even their number, however not always that of the participant alone in a multiply determined lapsed world – the only world there is, and is still heir to illusion, treachery and oppression (so much so for queer men and for a Nigerian exile unable to seek Nigerian domicile because of severe anti-gay laws and practices). Romance always says, Sondheim suggests, that, ‘there’s a place for us’. But is there?

“ I wouldn’t want my dad to take me back to Nigeria. …”.

“Achike –“

“ I know, I know. I’m not naive. I know I’m not welcome here. I know that. But I am here, and that’s all there. It’s all I have. Even if England doesn’t want me. Even if there’s no place for me. I’m here now. It’s done. I’m here.”

“Where is there a place for us?” Ekene said. “There’s nowhere.”

Achike wondered. Where was a place where they could be black and gay and safe?[26]

The question recalls the book of essays edited by Derek Owusu in 2019 to which Nzelu contributed: Safe: On Black British Men Reclaiming Space, about which, as I say above, I have previously blogged. Yet The monster from which none of us is safe if we have experienced and internalised exclusion and oppression, as Ekene (sexually abused by his uncle, physically and emotionally by his biological father and unprotected by his too passive mother) has more than most persons. And though Ekene is a fictional persona his equivalents continue to exist hidden in plain sight in all communities, all genders, races and other diversities. The issue in the novel is that safety is a feeling threatened from within by our past if our control of the emotion from that past is insecure, so that when it emerges, it emerges as a monster – like The Kraken in Tennyson’s great neglected poem; who might die if fully exposed to scrutiny.

From the outset the tidily controlled is necessarily disturbed by something ‘wild’ that seeks expression. Whilst Achike might be ‘reined in to himself’ his tunes can play out, ‘wild again, like the first time it was ever played’.[27] Communicated to Ekene, the latter gets lost in this communicated and introjected inner wildness:

… . A moment ago Ekene was immediate, the spark of electricity. Now he is sparks in moving air, diffuse, dispelled, everywhere, wild to hold.

Ekene is directly in front of Achike, and yet Achike wonders where he is gone. … He wants him back, the boy who was here.[28]

If any of us have the chance of ‘redemption’ (the word chimes in the later parts of the novel more insistently than earlier (of course I do not think religious redemption as such is intended) the Kraken or Leviathan must be exposed:

Ekene had come to church to feel lighter, to feel free of such questions, but he could not help feeling that something was emerging from him – no creature underneath his skin, only more of himself.[29]

And that thing is submerged not under water but its fluid social equivalent – language. What did Ekene want of Chibuike at this time?

Caretaker. Martyr. Father. None of these described the whole truth. Underneath the words still moved some wild, insubordinate thing that this language could never hold.[30]

In this account of the novel I may have created too many spoilers but I have endeavoured not to create the one that separately created such frisson and shock when both my husband and I read it: calling out from our silence as each lay at different times reading it in bed. This was because you must read this novel for yourself. I suspect it is different as an experience for different readers but great nevertheless and always. If it isn’t on the Booker list, the judges can only be dead to new and wild beauty.

All the best

Steve

[1] Okechukwu Nzelu (2022: 254) Here Again Now London, Dialogue Books

[2] Ibid: 269

[3] Ibid 7

[4] Ibid: 8

[5] Ibid: 211

[6] Ibid: 10

[7] Ibid: 63

[8] See ibid: 61 and 271 for two instances of the use of this phrase.

[9] The phrase seen on both ibid: 270 & 271.

[10] Ibid: 271

[11] Ibid: 281

[12] Ibid: 34f.

[13] Ibid: 41

[14] Ibid: 253

[15] Ibid: 38

[16] Available easily at: https://www.thoughtco.com/child-is-the-father-of-man-3975052

[17] Nzelu op.cit: 255 Read the whole page.

[18] T.S. Eliot (1919). Tradition and the Individual Talent. Available at: Tradition and the Individual Talent by T. S. Eliot | Poetry Foundation

[19] T.S. Eliot (1915). The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Available at: The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock by T. S. Eliot | Poetry Magazine (poetryfoundation.org)

[20] Nzelu op.cit: 267

[21] Ibid: 268

[22] Ibid: 59

[23] Ibid: 6. Compare Paradise Lost Book V available at: https://milton.host.dartmouth.edu/reading_room/pl/book_5/text.shtml

…….. me thought [ 35 ]

Close at mine ear one call’d me forth to walk

With gentle voice, I thought it thine; it said,

Why sleepst thou Eve? now is the pleasant time,

The cool, the silent, save where silence yields

To the night-warbling Bird, that now awake [ 40 ]

Tunes sweetest his love-labor’d song; now reignes

Full Orb’d the Moon, and with more pleasing light

Shadowie sets off the face of things; in vain,

If none regard; Heav’n wakes with all his eyes,

Whom to behold but thee, Natures desire, [ 45 ]

In whose sight all things joy, with ravishment

Attracted by thy beauty still to gaze.

I rose as at thy call, but found thee not;

[24] Ibid: 47

[25] Paradise Lost Book XII available at: https://milton.host.dartmouth.edu/reading_room/pl/book_12/text.shtml

[26] Nzelu op.cit: 73

[27] Ibid: 5

[28] Ibid: 46

[29] Ibid: 254

[30] Ibid: 254f.

One thought on “‘Could he live with the man forever, and be his – what? … There was no language for what should happen next’. ‘What were they, after all?’ This blog reflects on a novel that, I’d assert, queers even the gay literature it advances upon and goes well beyond: Okechukwu Nzelu (2022) Here Again Now @NzeluWrites.”