Early Spanish still lifes, those of Sánchez Cotán (for instance), can be interpreted as promoting the value of ‘a framing space’ in which to place singular objects.[1] However, later examples of the ‘genre’ emphasise, in Antonio Arellano’s words about Tomás Hiépes, the ‘copious’ fulfilment of that space.[2] This blog sets out to suggest that this is also true if we consider apparently still moments in time primarily as a containing space for ‘a sense of movement’ that demands detection by engaged viewers.[3] It reflects on still lifes currently in the Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland: from Reflections and Discussions in my free time on some of the Paintings, as part of a personal learning project related to the Golden Age of Spanish Painting (No.5).

Before insisting that a still life artist’s treatment of the dimensions of space and time give us the most exciting entry point into those paintings we probably need to look into the issues raised by creating typologies of art genres. The genre in question was variously called still life (originally from the Dutch categorisation of the mid seventeenth century) or nature morte (from the French re-categorisation in the eighteenth century). When we look at artworks, we can forget that the making of some of the pictures we name as examples of a particular category come from times well before the category was either named or described in a very specific way as independent of other art works. Moreover, some of these examples may also have been considered primarily to be something other than just a work of art, or at least not only as such. Thus Erika Langmuir shows that Roman culture developed, from Greek models known to them, categories of ‘wall painting representing fruit and other provisions’. These were interior decoration of a private villa (and sometimes self-advertisement of the inhabiting family’s supposed hospitable qualities – or an idealised version of those) known as xenia. These represented, according to Vitruvius, the riches of local grown or reared vegetable or animal produce that were made available to their foreign guests as gifts.[6] These wall-paintings were not discrete from the homes they decorated. Discrete identity only becomes to be a requirement of art that has itself become a commodity rather than being a practice used to represent objects for another purpose. Nevertheless, xenia may pass as an origin for still-life.

Moreover, they were not alone an example of paintings in which objects were represented for different reasons. Even by 1650 when a term recognisable as a name for the independent art category, stilleven in Dutch, those other traditions of painting still ‘sullied’ any categorical purity applied to those pictures pretending to the title. Langmuir begins her short but wonderful book on Still Life by looking at the traditions that met a need to represent everyday objects in earlier painting, naming three such traditions. We have already hinted at a case for xenia that were primarily of objects and fed into later forms of still life. However, in a second strand of tradition, objects were used in several other genres for other than obvious reasons of representing reality (in mythological, history or sacred painting for instance) to represent an abstraction, sometimes named as iconic or as symbolic of a certain ethical virtue or abstract characteristic of learning about thought, emotion or sensation. These appeared in allegories or religious symbols and sometimes had coded iconographic meaning, such as lilies denoting the Virgin Mary’s chastity and purity, or social emblems, like the symbolic accoutrements of a monarch’s office. It can be argued in fact that the vanitas theme, so often attached to worldly objects, is a version of this.

A third type is the picture of ‘low’ or common life, which might also be traced to the classical origins described by Pliny the Elder as a rhyparographos (‘painter of filth’), where filth equated with ‘sordid subjects’ from the ‘baser’ (kitchens and laundry and so on) aspects of domestic life of the lower social classes.[7] In Holland later, and in Spain with a complex multiple origin, this connected to traditions of the genre painting and narratives of a wider national social life in the picaresque novel.[8] Jordan and Cherry, for instance, connect one instance of such painting to the term bodegón; a term singular to Spain. In an early use by Pacheco, about his son-in-law Velázquez, the word referred to a kind of ‘humble eating place’ – a tavern or beer cellar. Such an origin connects some Velázquez paintings (such as The Waterseller of Seville of 1623) to the rhyparographos strand in painting tradition, even though at present the term has, in Spain, a similar reference to what in Britain we call ‘still life’. In a 1985 essay Jordan cites a 1611 definition of the term as meaning the ‘basement or low portal, within which is a cellar where he who does not have anyone to cook for him can find a meal, and with it a drink’.[9] And we will see the term also used to distinguish the early appearance of very innovative kind of still life originated by Juan Sánchez Cotán and which tends to be buried under Italianate Baroque traditions during the seventeenth century, even in Spain.

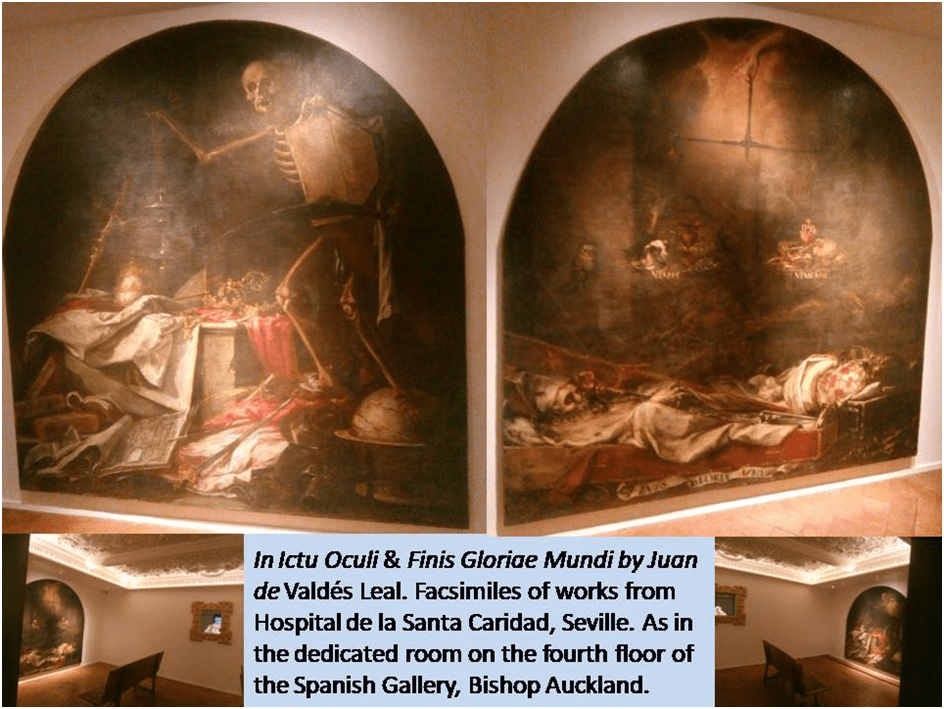

This complex and convoluted emergence of a genre in art, that referenced social themes originally, means that, when we turn to the relatively independent nature of Spanish culture in the Baroque period, there are still multiple kinds of ‘still life’ common in Spanish painting. These include those I have pointed to in past blogs – one on Murillo, for instance (the link here connects to that blog), wherein flowers cast by a host of cherubs serves a symbolic function in terms of ideas of love, charity and the passage of time. However, in what follows I will confine myself largely to those independent still lifes, except where the literature guides me otherwise. In the case of frescoes dedicated to the themes of Vanitas by Valdés Leal, the literatures does so because certain strands of a secularised vanitas theme survive in still life that do not necessarily reference religious meaning or codes but which derive from the religious tradition. So, although I will confine myself to examples from the Gallery that can be categorised as ‘independent still lifes’ (independent that is of other obvious genres of painting), we will start with examining Valdés Leal’s Finis Gloriae Mundi (The End of Worldly Glory) as this is a painting – found as a facsimile in the Spanish Gallery – investigated by Jordan and Cherry in their fine book of 1995 on the subject (there is a copy in the public reading room of the Gallery) of Spanish varieties of still life. The independent still lifes are however dispersed across three floors of the Gallery. We see the determinedly Spanish variations of the genre on the ground floor and a series of four still lifes by Mateo Cerezo (who died young in a way appropriate to the feel of death in his still-life paintings) on the first floor. There is a late Italianate example on the third floor (by Belvedere).

But let’s start in that estranged place on the fifth floor and with a fine facsimile of Valdés Leal’s Finis Gloriae Mundi [The End of Worldly Glory] and its companion piece. There is a fine discussion by Jordan and Cherry of these paintings which translates the Spanish terms required to understand the vanitas allegory that remains unexplained in the Gallery’s captions.

Objects are always the subject of still life, as we have seen, but this painting divides some objects from the world as divided into those tending to evil (and Hell) and those tending to divine good (and salvation). As Jordan and Cherry say Finis Gloriae Mundi:

… depicts, in gruesome detail, the rotting, maggot-infested corpses of a bishop and a knight. Above is the hand of Christ holding a pair of scales: nothing more (ni mas) than the seven deadly sins signified by the animals in one scale – is required for perdition, whereas noticing less (ni menos) than prayer and repentance – symbolised by instruments of penance and devotion piled up in the other scale – is needed for salvation.[10]

Live animals will later not be considered appropriate to still life (or nature morte) but even here these allegoric animals do not appear to have much motion other than internal e-motion, and this matters when we come to see that secular vanitas themes in later works deal directly with the decay of dead, but once living, materials without any obvious link to a soteriological framework. Moreover as Cherry and Jordan say of another religious allegoric work by Valdés Leal, these objects are shown in vague and dream-like outline as if they were less than ‘real’ spiritual entities (of good and evil) because, as the artist was to inevitably suggest, objects of art are themselves potentially idolatrous or at best a fictional suggestion of truth: part of the ‘illusory nature of worldly life’.[11] In contrast, still life was to assert the solidity of sublunary reality – however dangerous to the soul or ethical human life – and however potently the application of physical decay was used for moral purposes. This later still-life was arguably to have a much closer relationship to Protestant than Counter-Reformation Catholic thought. They turn from a preoccupation with eternity to one of the inexorable and inescapable in time and space as we know them as constrictions on our imaginative potential – the object of Don Quixote’s quest, in short.

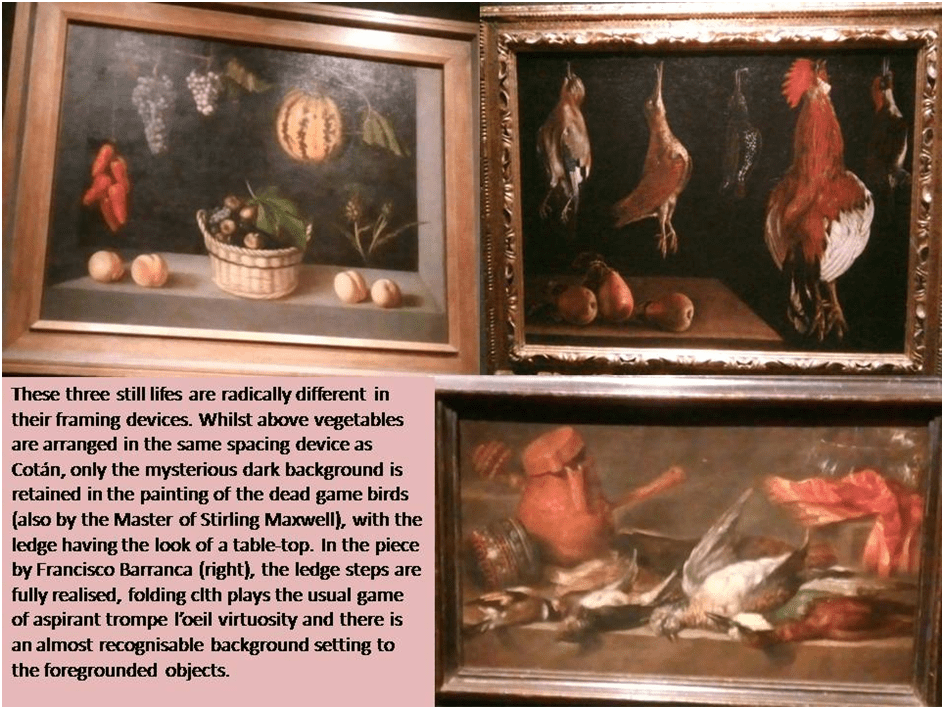

But, in order to pursue this idea, let’s go back to early history of other strands in the origin of Spanish art. The Spanish Gallery has no works known to be by Cotán, but his method (as described by Jordan and Cherry) is certainly present in some works, and these bear much scrutiny. These are labelled bodegónes but this usage, though prior to it, should not be confused with Pacheco’s use of the word to define works by Velázquez, mentioned above. Indeed it is only when we scrutinise them without too cluttered a set of expectations (for instance that expectation, misapplied from practice with landscape painting in the Italian Renaissance, of finding a unitary perspective and single vanishing point) that we will see the bold differences from other paintings in these works. Jordan and Cherry are deeply impressive in characterising this mode of painting but do not take their conclusions in the direction speculative mavericks like I do. Jordan praised Cotán for inventing an artistic form, although with some small Dutch influence in minor aspects, wherein the Spaniard alone went beyond being ‘bound by what he saw’ and ‘seems freed by his imagination to pursue extremes of artifice found nowhere else in Europe’ (my italics).[12] Cotán’s methodology is more fully described in the collaboration work Jordan did with Cherry in London as the arrangement of everyday objects:

… in front of a framing space that appears to be a niche or window. This architectural setting allowed him to achieve a powerful sensation of real space, through its precise perspectival construction and the strong modelling of forms in light and shadow. Both the visual evidence of the paintings and the entries in the inventory of his studio confirm that he painted the window first, then added the fruit and vegetables. …

The framing space, or window, in Sánchez Cotán’s still lifes would probably have been recognised by contemporaries as a cantarero, or primitive larder. The hanging of fruits and vegetables from strings attached somewhere above was an allusion to actual practice that helped to keep them from spoiling. None of the compositions suggests the random disorder of a larder shelf, however, so it would be a mistake to forget that these are artfully arranged compositions.[13]

I find that prose a fascinating play upon the contradictions in responding to these works by the master and his contemporary followers. For, representations of a primitive larder or not, the paintings eradicate any chance of having detailed perspective on the framing object by placing it in a space that presents an empty and non-perspectival black darkness at its rear. This may create an illusion of ‘real space’ (and of a real cantarero) but it also reminds us that our perception is illusory, however solid seem its elements. Even the manner in which the framing space stands in relation to the actual frame of the two-dimensional picture adds to this sense of artful illusion of which Sánchez Cotán requires the viewer to take notice, as in this famous and beautiful example from 1602, Still Life with Game Fowl, Fruit and Vegetables. This latter picture by the way contains an representation of a cardoon (a decidedly ‘peasant’ foodstuff picked in the wild) with which this painter was strongly associated.

The Spanish Gallery has one work, attributed to the shadowy Master of Stirling-Maxwell, that follows this pattern with a use of the framing space as comprehensive as one of Cotán’s. However, even minimal changes of that internal frame produce a very different kind of painting and one that is much nearer to the model that was to become a dominant one. This is shown in the second painting (of game birds) where the framing device is less comprehensive and may represent a table with the upper surface from which the game birds hang being made less visible, if visible at all. The three still lifes are, to my mind, radically different in their framing devices. The second (top right) example retains only the mysterious dark background (even though it may also be by the Master of Stirling Maxwell), with the ledge having the look of a table-top. In the piece by Francisco Barranco (bottom right), the ledge steps are fully realised. A cloth falling into folds plays the usual game of aspirant trompe l’oeil virtuosity of Baroque art and there is an almost recognisably ‘real’ background setting to the foregrounded objects.

Soon the framing device will be replaced by an obviously recognisable table found in later paintings (of which more later) which was to become a convention of the painting (and used by Cezanne). This move to naturalistic setting is fundamental I think (though it seems a contradiction) to the disposal of the self-consciousness of the artist demonstrating his making of the image to a pretence that that the image is merely skilfully aping its referent with its making process (the art, craft or technique of composition itself) made less visible to the spectator. The fact of composition is rendered patent in the framing space and these become paintings as much about the space between, in front and behind of objects as the objects themselves. As the genre becomes more fully established, however, artful clutter and copiousness takes the place of acknowledged artifice; the accumulation of things in a ‘wasteful’ manner usurps the honour given to concepts of the maintenance of freshness and artful storage as a subject. I am inclined to think that as still life develops it takes on the forms of commodity capitalism – the endless production of surplus and waste as a lever of progress. For this reason I could wish that Michael Petry had developed his ideas about the representation of ‘food’ in still life with more eye to differences such as those I’m pointing to, for (as we see above) the message of still life need not be the apparently boundless ‘bounty of present life’. It could alternatively be the organisational care needed to preserve the life in our foodstuffs in an optimal fashion by giving regard to the need for space that delays decay and reduces the waste so fundamental to commodity capitalism.[14]

I have noted, for instance, that when artists show serious metaphysical intentions in painting objects they do so by limiting their selection of the number and type of those objects. Nowhere is that more obvious than in Erika Langmuir’s brilliant reading of Francisco de Zurbarán’s (1630) A Cup of Water and a Rose in terms of the imagery (and their appearance as objects in a later painting) of a soteriological devotion to the Immaculate virgin Mary: ‘Solemnly arranged in a row at regular intervals, the symbolic objects guide our meditations like beads strung on a rosary’.[15] In effect, the appeal of still life, when it was not to aristocratic self-advertisement of surplus wealth was to the production of surplus value I’d suggest, and with it the exploitation of labour that gives excess a deathly tinge. Of course, in doing so, it pretends to become not about the space needed to think and work and preserve life-giving things like food but the tragedy of time as a producer of inevitable death and waste material. This is certainly how I see (without of course anything but my ‘gut’ responses to help me) the four still lifes of Mateo Cerezo; beautiful as they are and tragic as is his story. All four are (despite my reproduction) identical in size in order to fit over the door lintels of an aristocratic house. They celebrate surplus. There is more to say, since they too are vanitas paintings since they speak of the inevitably of death and decay (perhaps more so because of their crowded nature). What they fail to show, unlike the admittedly grim versions in Valdés Leal but also unlike the beauty in Zurbarán, is any hope at all of salvation.

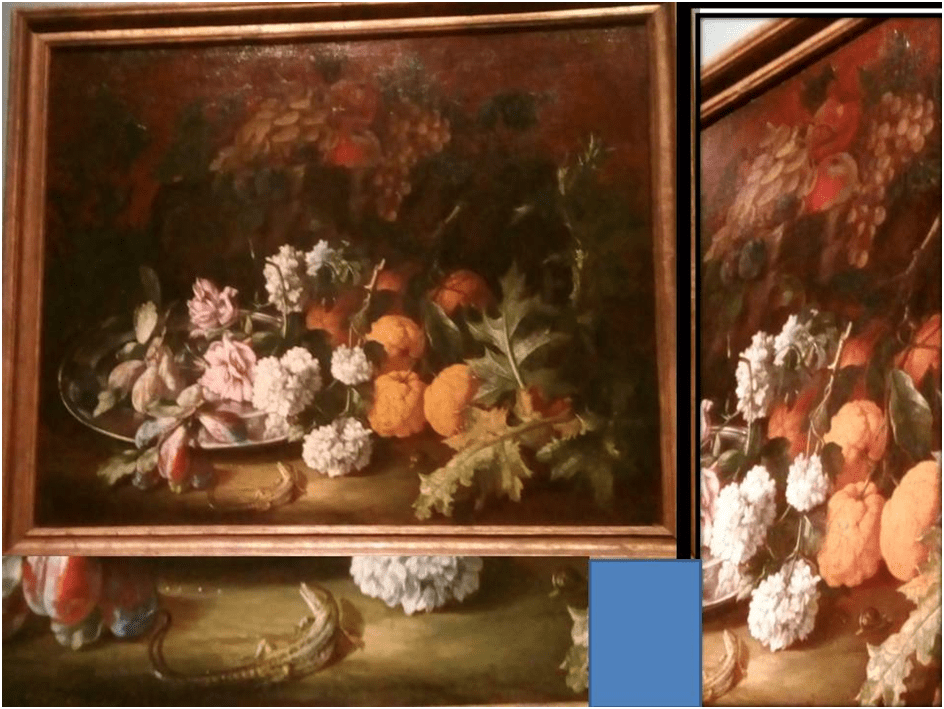

This story of change is perhaps also evident in comparing the developments that led to the masterworks of Antonio de Pereda (1611-1678). Pereda is obsessed with Italianate Baroque trompe l’oeil effects that attempt to rival the classical example of Zeuxis. It is always so, perhaps, when grapes become the subject of still life because Zeuxis’ grapes were supposed so realistic by Pliny that they fooled the birds. In Pereda however, though there is a delight in the copiousness of the fruit examples (grapes cluster and reflect on each other), there is also spatial simplicity and differentiation between the fruit types. Once flowers are the subject, especially in the work of Cristóbal Ramírez de Arellano (active 1630s / 40s) there is also a delight in the containers built by artful craft to house them. An examples is the ‘historiated bronze vases and ornamented pedestals’ mentioned by Jordan and Cherry and attributed to the Italianisation of the Spanish court by Philip IV.[16] Another example is the fine crystal vase in the Spanish Gallery Arellano, delighting in that light through crystal and water distortions in its artistically self-conscious trompe l’oeil effects.

Perhaps the best illustration of later (and even more Italianate) still life paintings are those two remaining ones in the Gallery. The last we see is by Andrea Belvedere (1652 – 1732) and even more fits Johnson and Cherry’s fine description of Arellano’s work earlier, wherein time and motion are celebrated but decay seen as inevitable. They say the earlier painter has a ‘sense of movement, originating not from any external force but from the ebbing life of the flowers themselves’ which ‘convey a generous and suggestive image of nature’.[17] Though Belvedere is more hackneyed in manner than Arellano perhaps, he also wants to convey the sense of both copious bounty and constant motion This is why I think he includes that charming flexible-bodied gecko in the painting and those diagonals betokening the downward potential movement of heavy flower heads.

Described by Jordan and Cherry as ‘one of the most spectacular’ Italian influenced still lifes with emblematic figure and distant landscape (just to confuse us more with the multiple perspectives I think) is Hiépes’ A Girl Making Nosegays and for me this is one of the star pieces of the Gallery. It combines a kind of allegory. The girl is both coy, vulnerable and offered for possession by the male gaze, gathering nosegays while she may. A small serpent in the bottom right corner may indicate the story of Eve in another garden but in a highly secularised form. The lush delight in high quality coloured and patterned (and therefore expensive) tiling as well as excessive flora remains us of the excess involved here which is both beautiful ad threatening. Much here is going to waste, not least the overwhelming multiplicity of objects on view which cause our eyes to saccade from bloom to bloom.

The patterned pots and baskets each also tell a story of the production of luxury commodities: the broken shard of one of the expensive tiles makes a jagged and dangerous appearance to show that time brings destruction to not just to the organic forms of worldly and material life. Much is wasted in the young lady’s labour. But ‘most spectacular’ (in Jordan and Cherry’s words) this piece clearly is. It illustrates how space for freer movement has been supplanted by the over-copiousness of life under Imperialism and the beginnings of mercantilism and eventually commodity capitalism. It’s sad but beautiful. Unfortunately too, we are probably encouraged by such art to think it is also unchangeable and inevitable. God save us!

My next blog (no. 6 in this series) will be one on the subject of three-dimensional polychrome statuary and frieze work, of which there are many brilliant examples in the Spanish gallery. These polychrome painted works are looked at in their own terms and in terms of their how they contributed to the naturalistic turn in Spanish painting that is sometimes attributed to their influence using the concept of the paragone. The examples in the gallery cover a long historical period and one marble monochrome work (The Tomb of Cardinal Tavera existing in facsimile alone in the gallery) will be used to consider why polychrome mattered in the representation of both the visionary and the real for Spanish artists. Hope I see someone there.

All the best Steve

[1] William B. Jordan & Peter Cherry (1995: 29) Spanish Still Life: from Velázquez to Goya London, National Gallery Press with Yale University Press.

[2]Cited Ibid: 118.

[3] Ibid: 136

[4] ibid: 29.

[5]Cited Ibid: 118.

[6] Erika Langmuir (2010: 17ff.) A Closer Look: Still Life London, National Gallery Co. Ltd.

[7] Ibid: 21

[8] Ibid: 13

[9] Sebastián de Corrorrubias in Tresoro de la lengua castellano (1611) in William B. Jordan (1985: 16) Spanish Still Life in the Golden Age 1600-1650 Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum

[10] William B. Jordan & Peter Cherry op.cit: 23

[11] Ibid: 24

[12] Jordan op.cit: 7

[13] Jordan & Cherry op.cit: 29

[14] Michael Petry (2013: 78f.) Nature Morte London, Thames & Hudson Ltd.

[15] Langmuir op.cit: 73 (read 72f. for full exposition of the painting)

[16] Jordan & Cherry op.cit: 130

[17] ibid: 136 (Caption to Fig. 51)

17 thoughts on “Early Spanish still lifes can be interpreted as promoting the value of ‘a framing space’ in which to place singular objects. However, later examples emphasise, in Antonio Arellano’s words about Tomás Hiépes, the ‘copious’ fulfilment of that space. This blog reflects on still lifes currently in the Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland: from Reflections and Discussions in my free time on some of the Paintings, as part of a personal learning project related to the Golden Age of Spanish Painting (No.5).”