Speaking of Claudio Bravo’s rejection of ‘abstraction’ as an aim in aesthetic creation, Edward Lucie Smith summarises the artist’s view by saying: ‘the human mind is trained to look for images and will find them in the most unpromising places’.[1] However this blog suggests that it is the fact that the artist leaves the viewer to detect for themselves stories, ‘iconographic meaning’, symbolic reference or influence from past masters which makes Claudio Bravo’s art into queer art.

This blog again looks at what makes an artist a queer artist. This is not just a matter of distinguishing between artists who identify as ‘gay’, or even ‘queer’, for I don’t think it is a useful way of looking at art merely through accidents of biography, although such identities can, if prevalent in the public realm, lead to interpretations of the stories or meanings in art. I would say that there has to something queer in the relationship of the viewer to the artwork, such that no norms of communication or assumption can be held to resolve the puzzle we feel when we view that art as its engaged viewer. This does not mean that we wonder if there is an intention and think that, should we ask the artist, that this intention would be made clear but that there will never be such clarity about any single meaning, although there will be many multiple and often contradictory meanings and stories generated by the viewer’s gaze on the painting and its objects and figures.

I think in extension that I do not think the queering of our response to an artist has to do only with limited domains of sex/gender, though these might be involved. An example of the latter is Bravo’s Infantæ of 1970 which was a collage of features both male and female from across the seventeenth-century Royal family of Spain and referenced Veláquez’s practice of using a boy to stand in for the Princess Margarita (in order to ensure that she did not tire) when painting Las Meninas in 1656. This painting was intended, as was the exhibition in toto, to be ‘as scandalous as possible’.[2] This was not just because the hermaphrodite image produced was naked, but because it defied every norm of painting Royal figures and, even more so, children (of any class or status), since the pose taken is provocatively sexual when transposed to nude form, even though it recalls that of the voluminously dressed Princess of the original. But shocking representational norms is not I think enough to produce a queer art and therefore I do not reproduce the painting here – use the link instead to view it. For this painting is an unusual one in the artist’s oeuvre and shocks more than it intrigues. It may be this very trait that John Canaday found ‘cheap and vulgar’ in his early review of the painters debut and second exhibitions.[3] The nearest examples are his erotic nudes of men of African origin (such as Black Nude of 1978 and David of 1979) and which sometimes feel to me not to escape the failings of the painterly exotic ‘orientalism’ of late nineteenth and early twentieth century painting, the values of which Sullivan believes they eschew.[4] Hence, since I can’t argue a case I don’t use these either.

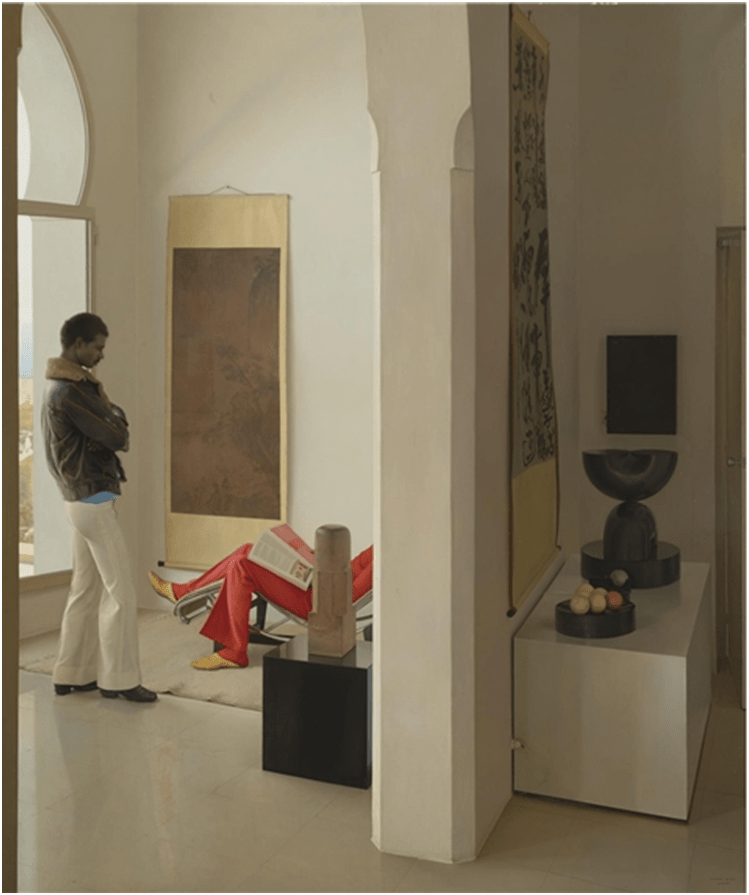

Eroticism may be the matter of an implied meaning, story or symbolic reference in a painting rather than use the blunt weapon of a naked body. Bravo himself said that the ‘most obviously erotic painting’ he’d ‘ever done’ was one named Lingam of 1975 (see below).

He even tells the story of the painting: ‘It represents a hustler who comes into your house, talks with you and creates an erotic situation. It is set in an everyday atmosphere’.[5] But the erotic and the scene, even in Bravo’s account do not seem to be at all of the same order. It is not clear even whether the designation of the standing Moroccan youth is so self-evidently a ‘hustler’. Bravo says the erotic is obvious after all, not because of what we see in the drama of the scene but, only in the painting’s ‘title’ (the meaning of lingam being thought obvious in my mind it isn’t hence my link to Wikipedia) ‘and in the fact that the phallic symbol is placed between the legs of the seated model’. He also mentions ‘erotic forms’ in the Max Bill sculpture in another room but also present in the painting. It is present of course but it is difficult to see these forms since they are in the dark shadow of a wall that blocks its access to light unlike the figures near the window. The lingam we know to be one Bravo brought himself in India but if it portend the sexually erotic in this scene, it does so without being at all sensual or even sensuous. The whole scene is relaxed not tense with sexual or other expectation.

In fact I think it is difficult to know what Bravo could mean by an ‘erotic situation’ and associating its cause entirely with the young man he calls a ‘hustler’. If anything this painting feels to me tell me more about the inequalities between the man standing and the one at home in this interior with its rather grandiosely orientalised aspects. Such aspects include the interior architecture and rich leisured luxury of the owner’s dressing gown and slippers. In fact, I think this painting is a visual presentation of the practice of aesthetic connoisseurship. In it a man (whose accommodation, possessions and clothing demonstrate the possession of money, status and luxurious leisure not available to the beautiful standing young man) confronts someone whom has not yet been made an available asset for consumption. The young man’s stance is in contradiction to the very formal art owned and displayed in this room. It gives him a kind of freedom from being owned, as a lingam can be owned, and thus a symbol perhaps of a much less status-bound in which the value of life can be appreciated without being entirely monetised. If it is queer, it is queer because it refuses to confirm norms which create hierarchies from the relatively elite status of objects (whether a home, artworks or furnishings). Its queerness is about escaping easy assessments of the meaning of identity not a confirmation of taste against what is considered cheap.

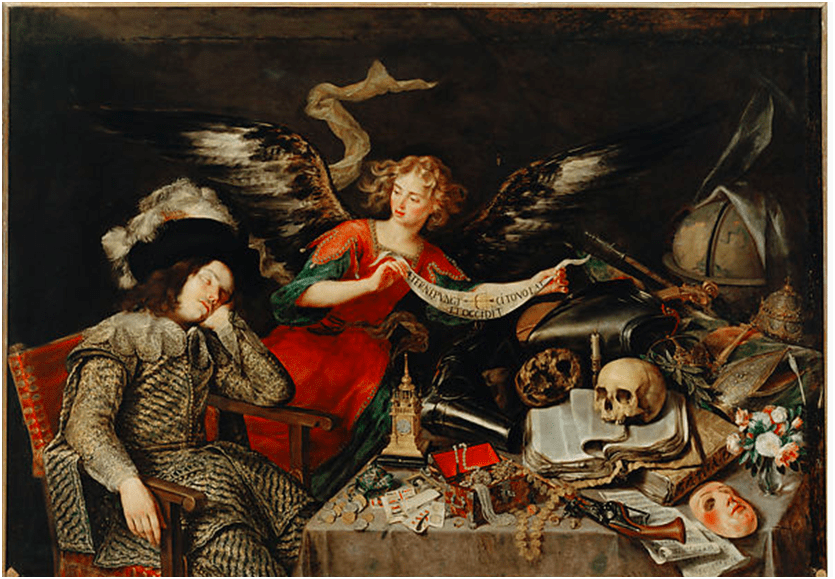

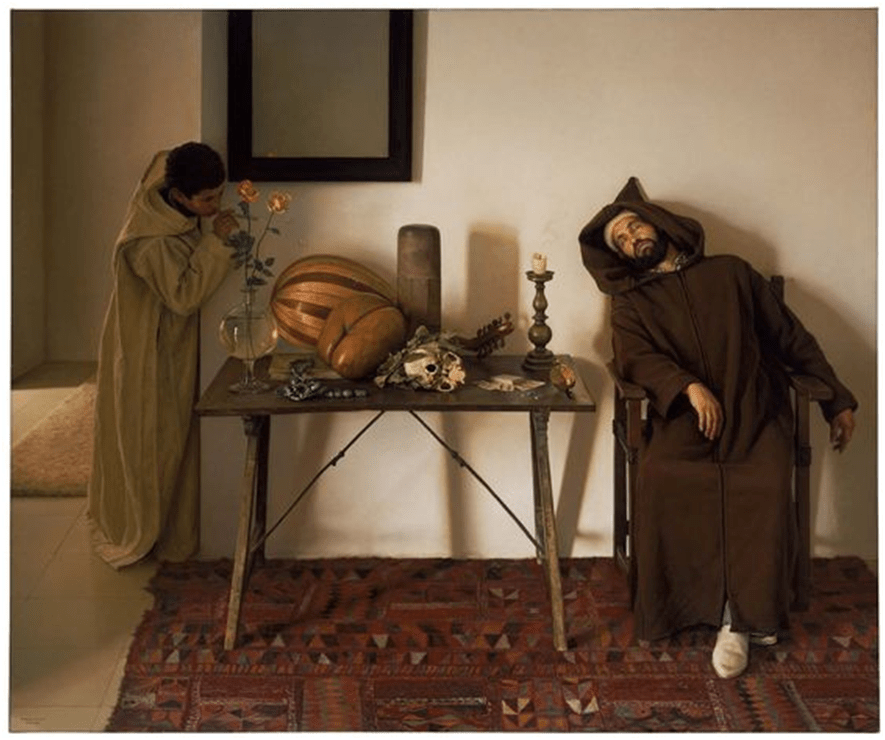

Indeed this is clearer if we look at a more famous Bravo painting in which the same lingam is represented. Sullivan argues that the painting Vanitas of 1981 is based on meditation of both still life painting and the common ‘sic transit gloria mundi (thus passes the glory of the world)’ Of Golden Age painters of the seventeenth century Spain such as Juan de Valdés Leal and Antonio de Pereda which symbolised human vanity in objects of beauty and the desire to possess them. Indeed he goes on to argue that Bravo’s Vanitas uses very directly the theme of Perez’s Knight’s Dream of 1650, ‘in which a young nobleman is shown sleeping beside a table piled high with the elements of a luxurious but vain worldly life’.[6]

Of course Bravo’s painting cannot be directly read from any of those examples, although the same links between imperial control of the world (the globe), formerly religious artefacts, and nature used as a commodity (floristry), all have their equivalents.

In Vanitas even the treatment of focus through the various transparent elements in the rich glass vase on the table that dominates the scene reminds one of seventeenth-century still-life, like this perhaps;

The owner of the table in Vanitas is dressed in the habit of a seventeenth-century monk, as indeed is the boy who steals a smell of the roses in a similar trompe l’oeil vase to that above – turning therefore briefly a commodity from a still life painting into something natural and sensual.

Yet why in the painting is the older man (whom I read as the ‘owner of the table’) confused with the accoutrements of the religious and penitent, whilst the objects on the table- and perhaps the focus of his dream – predominantly recall aesthetic form that appear to be OR represent (as the lingam does) body parts (anal and phallic) – ‘erotic shapes’ as Sullivan calls them. My own feeling is that this is not a condemnation of eroticism but a presentation of the distance of a rich life from any true moment of interchange of body or emotion. It is a painting where nature morte is a literal term – beautiful but cold. This mourning of the body in Bravo is a product of commodity capitalism, art as a reserve of the rich and the loss of response that is anything other than conventional or normalised.

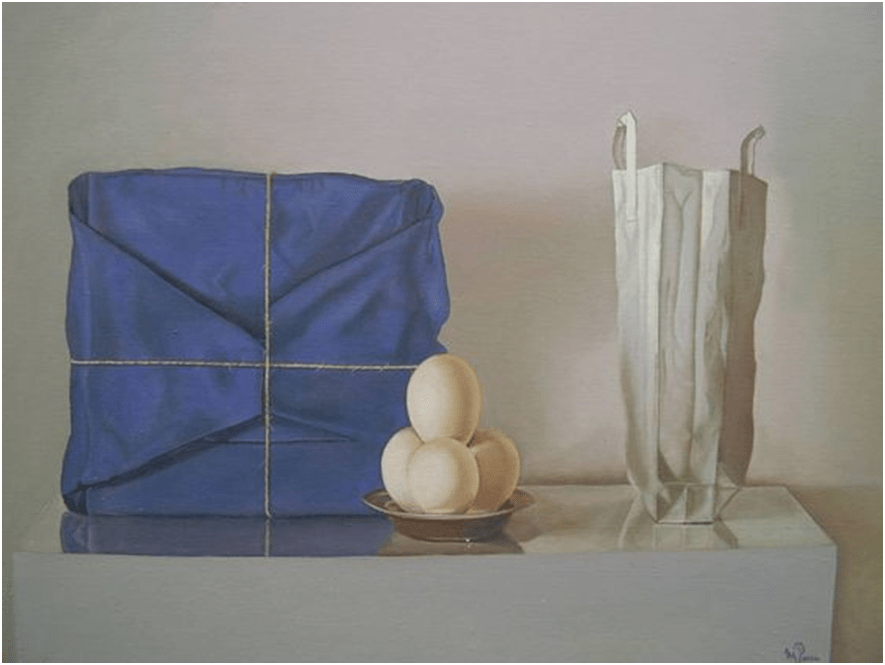

The problem with modern art in Bravo’s implied view (as I take it) is that those few who feel art is for them and their exclusive group (and them alone) are actually deadened to any response to it because they look only for the artifice of design – for what lies in the art abstracted from human meanings. One cause of this is surely the terrible prominence of abstraction as the aim of art in the mid-twentieth century (in ideology if not in the praxis of real artists) and the belief that what matters in art is abstraction alone; the distribution of two-dimensional forms across a blank surface. Herein lays another reason for Bravo’s turn back to seventeenth-century obsessions with trompe l’oeil effects of depths – exploitable by the use of steps and ledges that appear to project behind the surface space of the painting.[7] And with perceptual depth, Bravo also returns us to something like a more authentic response to objects by refusing then names which predetermine response. In my view that is why he invented a still-life that contained and was in its entirety a representation of packaging. Let’s look at the painting Blue Package with Ostrich Eggs from 1971.

My first thought about this painting is that the title neglects to mention the white paper bag also represented with in it, for this emphasises that packages are merely sealed containers. The painting could be seen as examples of sealed objects that contain materials (as ostrich eggs do too) and one that is open such that the issues of relative closure itself becomes a theme, emphasising that closed or open responses often depend on expectations of concealed meaning – indeed packaging functions entirely as a means to secrete meaning. There is a kind of paradox mixing these new objects of art (ones that have never before been objets d’art in the way other inanimate entities have). This is not the case for ostrich eggs which have been represented in and turned into art since the Middle Ages in Europe as exotic possessions. But even the meanings of ostrich eggs are never to be assumed and for me this quality of objects which conceal meaning (sometimes under other or contradictory meaning) is what characterises the artist which Sullivan could be referring to in his reference to some fans of the artist who speak of qualities of ‘silence’ and ‘secrecy’ related to the painter and which he sees as symbolised in the use of half-open doors in the paintings. I see this operating more generally as a quality of refusal of obvious or expected meaning – a sense that something (perhaps the whole point of the painting) is concealed and must, and on only, be teased out in relationship to the painting by the viewer from clues and hints towards meaning.

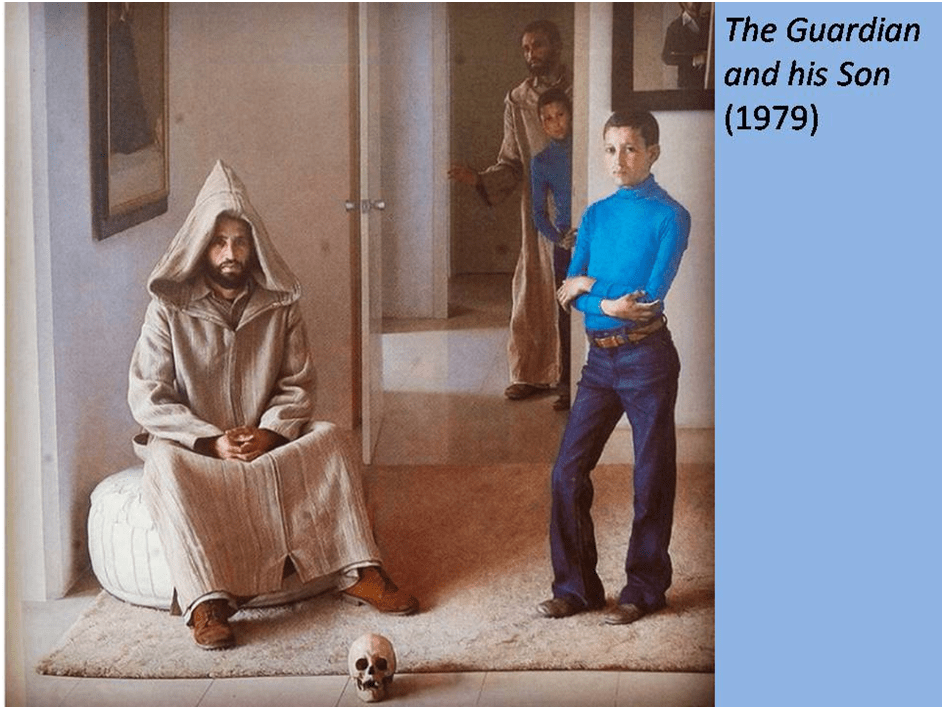

In The Guardian and his Son of 1979 the whole is clouded in the ambiguity of doubling. It was prompted says Bravo by identical twins working in a graveyard near his home (who then visited his home for some unstated reason) which cause him to use them as models in one painting. But not stopping with his twins. Bravo then doubled every other figure in the painting, such that characters query each other and their meaning to each other. Even the skull is doubled but not visible in the partial reproduction above) for it is in the mirror with the artist’s self-portrait at the rear.[8]

Similarly, Bravo evokes copy of a master but varies nearly everything so that meaning is queered. Take for instance The Lamb (below) which recalls, but also radically differs from, Zurbarán’s Agnus Dei. In my view deliberate removal of the object or figure from ‘specific time or place by a lack of narrative detail’ as Sullivan puts it, is aimed at refusing conventional or easy closure of meaning for the viewer.[9]

This decontextualisation sometimes robs too queer sexual icons from obvious sexual meaning, as in the 1980 Red Carpet. The plate queers meaning and takes away some of the availability of the male as a sexual offering, although this painting is not clearly free of orientalist exoticism.

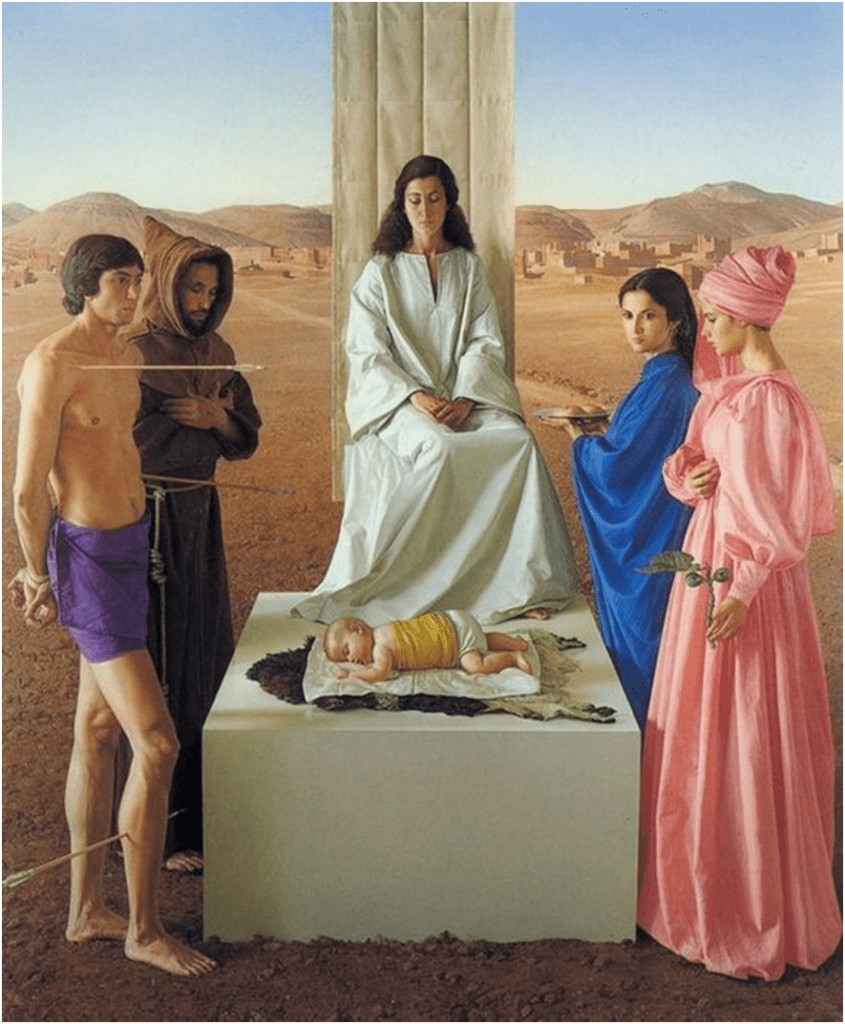

Sometimes decontextualisations take place on a much wider scale, where the whole of an Italian Renaissance master’s work is radically queered. Thus is the situation in Madonna of 1979/80.

Setting the scene in the terrain of the High Atlas Mountains only because the village of Imichil there held an annual husband-choice festival which recalled to him that the Madonna chose Joseph (not the other way round), it is clear than any link to context is still necessarily tenuous. It is matched as a strategy by placing together saints ‘virtually never’ (according to Sullivan) represented together (respectively from the viewer’s left, Sebastian (with arrows still implanted), Saint Francis, Agatha (with dismembered breasts) and Lucy, (with gouged eyes turned into figs hanging from a small fig branch)). There is too much contingency of placement here to yield easy meaning. A favourite de-contextualisation here is the obvious fusion of Francis’ habit with an Islamic djellabahs – here two were cut up by Bravo to clothe the model to ensure variation of texture. The Christ baby is not supported by his mother but lies on his face. Madonna appears very conscious of how she looks and how she is placed in rich fabric background so out of context of the High Atlas setting. It is all very queerly disturbing.

In The Temptation of Saint Anthony symbols from different cultures mix uncomfortably. The saint kneels on a Moroccan prayer-rug of lamb’s wool. The lamb pokes its tongue out at Andrew. The ugly devils of paintings by classical masters are still tempters here but are this by bearing images that ought to connate kindness and salvation. The lamb has been incontinent, and the swooping angel has a balance in which hearts are outweighed by hard cash. Darkness lies behind open doors and a sinister monk (in a blood-red djellebah) haunts the background in a way that destroys our sense of the physical dimensions of space. The angel and boy listening to pop music on earphones seem similar in face. Their meaning is far from clear or classifiable. The cock’s legs (lifted from a version by Bosch) seem totally out of any context at all.[10]

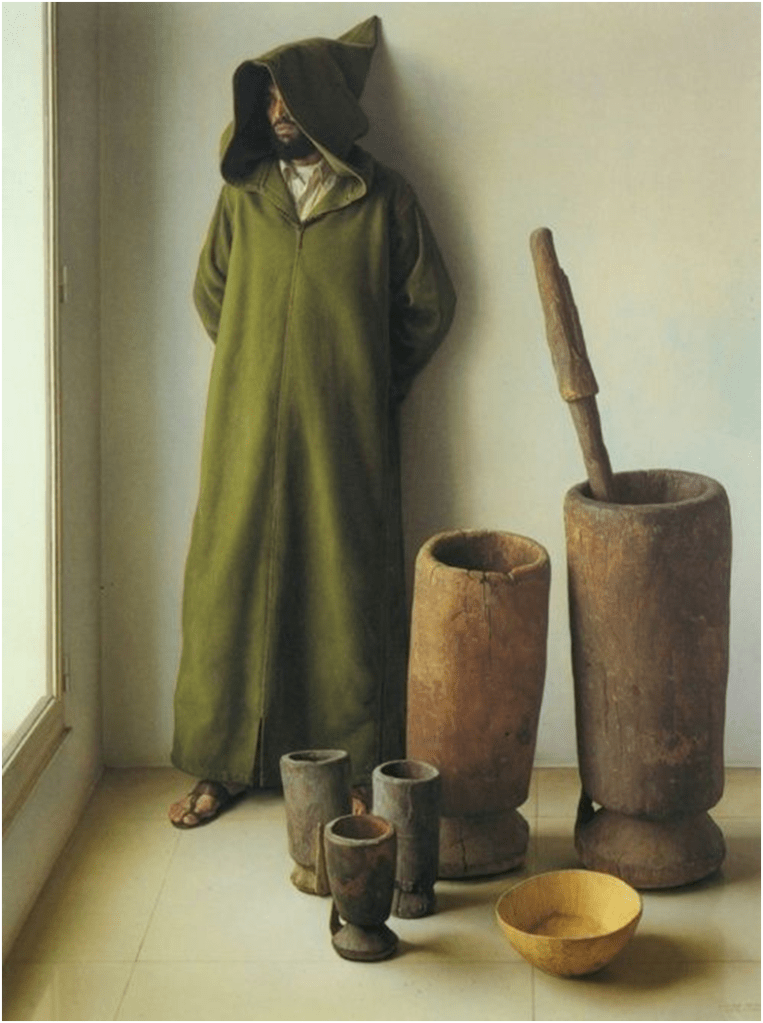

In my view this queering of meaning forces the viewer to keep looking and to stop assuming they know what art is all about and that they possess this secret. This is why I love the mystery of these paintings. Perhaps they even disrupt my reading of Zurbarán from which some figures derive. Why is the djellebah green in my final painting? Why mix items belonging to a rural external scene with a modern urban interior?

I love the painter. Make of my take what you will – which may be nothing. But it is still worth a look at the paintings.

All the best

Steve

[1] Edward Lucie-Smith (2014: Location 53 [text written 2006]) Claudio Bravo: Studies in World Art 22 Kindle ed. Cv/Visual Arts Research Archive.

[2] Edward J. Sullivan (1985: 14 – 107) Claudio Bravo New York, Rizzoli International Publications Inc.

[3] Ibid: 12

[4] Sullivan says that it is because these paintings (see ibid: 65 & 68) are so consciously of the ‘classical tradition’ (ibid: 55).

[5] Cited ibid: 67

[6] Ibid: 47-48

[7] See ibid: 36 on still life.

[8] Ibid: 78

[9] Ibid: 82

[10] Ibid: 82