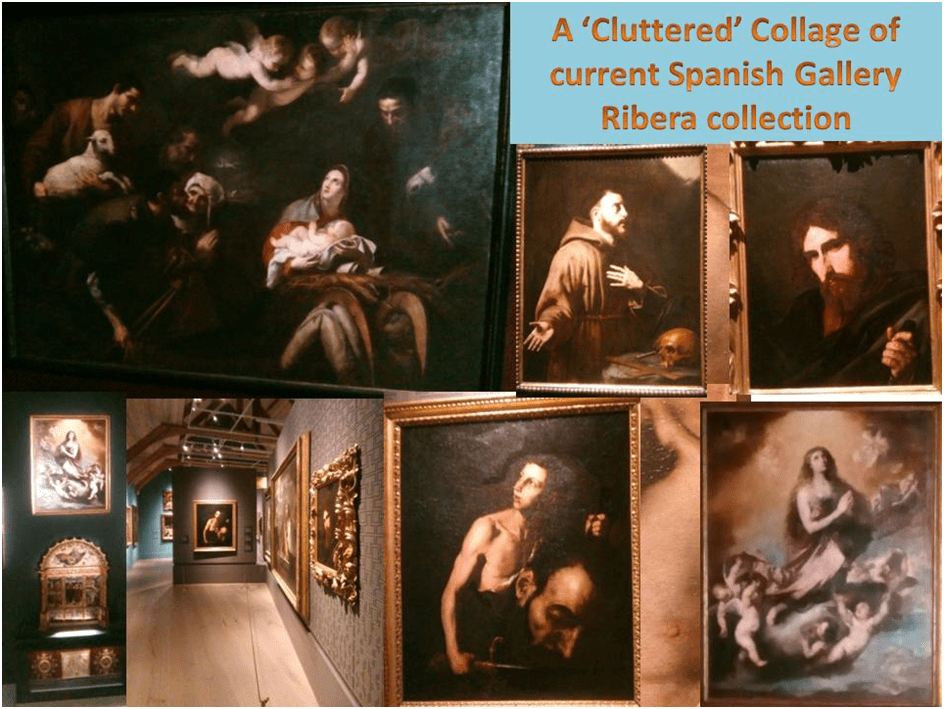

Despite the concentration of most on the extremities of intense interpersonal but external drama and violence in Jusepe Ribera’s art, Havelock Ellis valued it in terms of its ‘essential tenderness’: saying that in the ‘power of rendering loving devotion, of tender abandonment, associated with religious emotion, Ribera not only surpasses all his countrymen, but is scarcely excelled outside Spain’.[1] This blog reflects on works by Jusepe de Ribera (1591 – 1652) currently in the Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland: from Reflections and Discussions in my free time on some of the Paintings, as part of a personal learning project related to the Golden Age of Spanish Painting (No.4).

Ribera has long been a favourite painter of mine, though contemplating the paintings in the Spanish Gallery at Bishop Auckland has shifted my perceptions of him somewhat, not least because the books about Ribera I had to hand just weren’t very promising in ways into those paintings. They offered little new to viewing his paintings as primarily an elaboration of his interest in the apparent fleshliness of the physical body, especially the male body, and the frisson of his need to examine pain at the most visceral of levels. I had already blogged briefly on the last exhibition of Ribera I saw, at the lovely Dulwich Gallery, a few years ago, and there too my interest had been more in the very visceral levels of interest in bodily interactions between male figures that he explored. Indeed looking back at and reading this blog now rather embarrassingly shows me that I perhaps over-relished this extraordinary quality of delight in pain (not something I associate with myself at all). In this, for instance:

Ribera’s focus is not on men in relatively equal combat but in the passive suffering of a heroic body-figure under the hands of malign and/or justified torture. Usually this torture involves penetration of the skin and/or flesh – his favourite themes that run through his career being bodily punishment of an extreme kind in which the body surface is ruptured, cut and often manually or mechanically torn. Interested in the cruel mix of torture in which the victim’s bodily responses force him to collaborate in worsening his condition for instance, such as the strappado, but also penetration by weapons (St. Sebastian) or flaying, Ribera imagined different stages of gross torture (especially in the case of St Bartholomew), imagining him in twisting three-dimensional mobility of experience and expression of pain. He loves the moment of the scream through an open mouth – another orifice in the flesh where inside and outside meet in visions of wet (often blood-reddened and wet) rupture. His use of the idea of flaying in butchery emerges in the 1644 Bartholomew and the flaying of Marsyas. The flayer is shown at the minute when, having cut and exposed the flesh from skin (or hide in Marsyas’ case), he uses a hand (yes, even Apollo does this) to push down the patch of skin to expose a fresh wound.[2]

Yet though that genuinely embarrasses me, I think there is one perception from this brief blog – written on the train home from London – I want to carry over into the analysis in this, so it might as well be quoted here before laying down the ground work for my new approach. There I said – actually expanding on the reference to ‘three-dimensional mobility’ above:

Ribera’s men in pain are often partially exposed near the picture-plane, whilst the body-in-pain twists in two actual and one virtual dimension (of depth). Pain naturally invites this motion which is caught usually as a stasis torn out of arcs of embodied movement. In the paintings in this exhibition, we see how this affects the picture frame in 2-dimensions as a stretching of the body to fill all available spaces – with bodily extremities reaching out to the ultimate edges of the painting’s frame.[3]

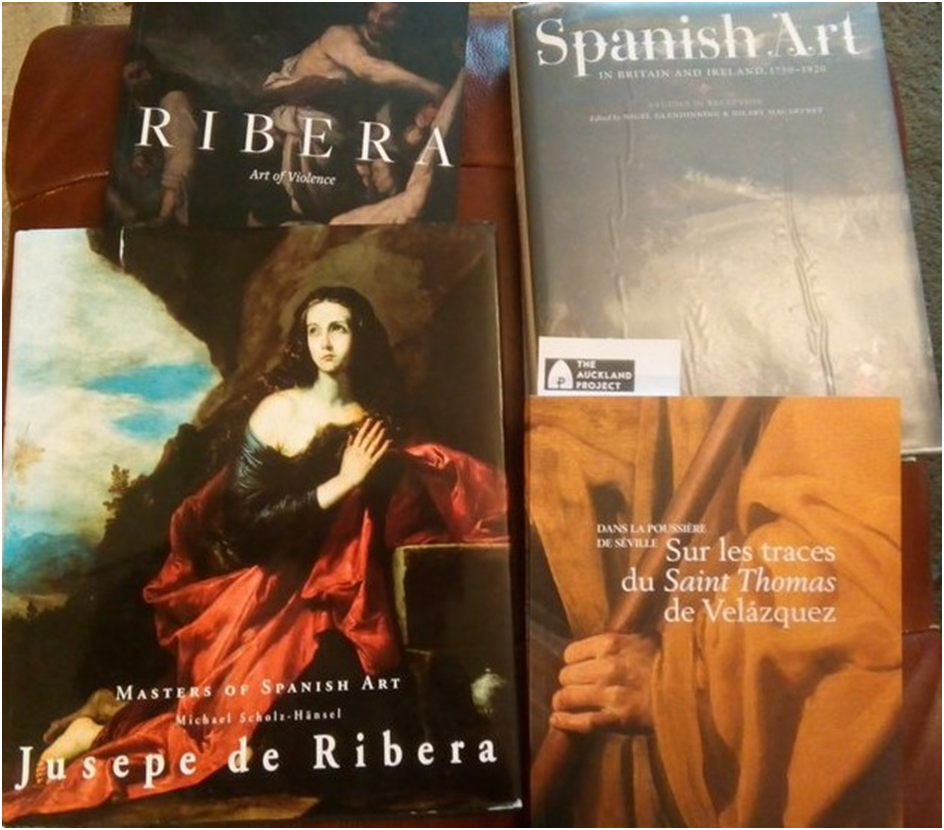

This quality of exploiting the material reality of the picture plane by reference to its framing to further imagine depth (both as a trompe l’oeil but also emotional or visionary effect – in suggesting a vision too intense for visual capture) – will also be important in the pictures I examine below. So my reading took two phases but was not deepened until I read texts purchased at the Spanish Gallery (and still available there in the gift shop as you enter). Let’s picture this reading first:

A characteristic of both new books here – both dealing with Ribera very partially of course – emphasise the liberation of an artist like Ribera from the stigma and marginalisation that courts Spanish art in the United Kingdom. Nigel Glendinning’s essay on Ribera’s reception is a comprehensive explanation of the specialisation of European, but specifically English too, treatment of Ribera as actually more Italian than Spanish (he lived in the dependent Spanish colony, together with the island of Sicily, of Naples). The Spanish Gallery has addressed this theme in emphasising the Spanishness of this Habsburg dependency and in widening the interest in Ribera from that which perceives him as a direct beneficiary of the innovations of Michelangelo Merisi (Michele Angelo Merigi or Amerighi) da Caravaggio, and even lesser Italian masters such as Guido Reni, and thus as an exception to Spanish art traditions.

Scholz-Hänsel does not look, as some do, for an alternative Spanish master in Ribalta to the Italian example of Caravaggio for the dramatic tenebrism in his work, for which he says there is no convincing evidence. He still insists however that even before his Italian sojourn and ‘while in Spain’ he attempted works that related directly to previous treatments of the same subjects by Caravaggio; ‘ he was already being steered in a particular direction’ (such as in the employment of startling detailed ‘observation of nature’ in figures and ‘employment of light effects’). To establish this he insists there is no need to evoke ‘a single master’, either Spanish or Italian, to explain this characteristic mode of working even from the beginning.[4] This line of enquiry that insists on the underlying Spanish take-up and transformation of Caravaggio is further explored in detail (but in French of course) in Contentin Dury & Guillaume Kientz’s book on the Spanish roots of Velazquez’s religious art (especially that portraying the apostles of Christ) amongst which entangled strands we find Ribera in particular.[5] All of this adds up the belief that the products of Ribera’s invention have roots elsewhere or paths of influence which are much less direct than those which honour one master alone, even when that master is Caravaggio. It is conceivable that Velazquez felt he was honouring an entirely Spanish tradition and Ribera as much its master (in apostolic painting at least) rather than appealing directly to Italy.

Why does this matter? My own feeling is that for Ribera living in ‘colonial’ Naples was a means of maintaining an identity that remained rooted in Spanish culture and traditions rather than being on the threshold of an Italian art world to which he aspired. I would say this mattered because otherwise we tend to treat his painting as an expression mainly of individual rather than cultural traits in which he invested himself with others. How else could we interpret the oft quoted view of his that he could best keep hold of a Spanish public for his paintings by not living in Spain, despite his expressed ‘fervent wish’, because ‘no-one would be interested in me because, if someone is there in person, he loses all respect’.[6] There is another clue to this conundrum and why residence in the wider Spanish European Empire was better than residence in Spain in an essay by Xavier Bray in 2018 who argues that Ribera had more access to important collectors in Spain through the Viceroys of the Southern Italian city-states of Naples and Palermo. Thus, for instance, one such viceroy, the Duke of Medina del Torres, gifted one work he purchased directly to Philip IV of Spain.[7]

However, my attempt to read Ribera as biased to his Spanish origins and traditions ignores the very real evidence of the artist’s embedding in networks beyond the Hapsburg territories and the very clear rivalry of Italian masters. Scholz-Hänsel is also certainly correct in seeing him in effect as summed up as ‘neither Spanish nor Italian’ but rather a locus in which many traditions were expressed, exchanged and metamorphosed.[8] Nevertheless I wanted to stress the evidence of the continuity in him, as an artist in order to introduce the view of Havelock Ellis, that this artist was as near as one might get to what he calls the ‘soul of Spain’ rather than just of Baroque Europe or a new school of the eighteenth-century fantasy through pupils like Salvator Rosa. I discovered Ellis as a writer on Spanish art, after many years of interest in him only as a crucial feature in the history of European ‘sexology’, in Nigel Glendinning & Hilary Macartney’s) Spanish Art in Britain and Ireland, 1750 – 1920, Studies in Reception. From thence springs the quotation from him in my title in which Ellis praises not his visceral and dramatic aspects but his ‘essential tenderness’: saying that in the ‘power of rendering loving devotion, of tender abandonment, associated with religious emotion, Ribera not only surpasses all his countrymen, but is scarcely excelled outside Spain’.[9] This stress on the Spanishness of Ribera in terms of the spiritual and softer emotions is I think welcome, especially when the current holdings of the Spanish Gallery of that artist are considered.

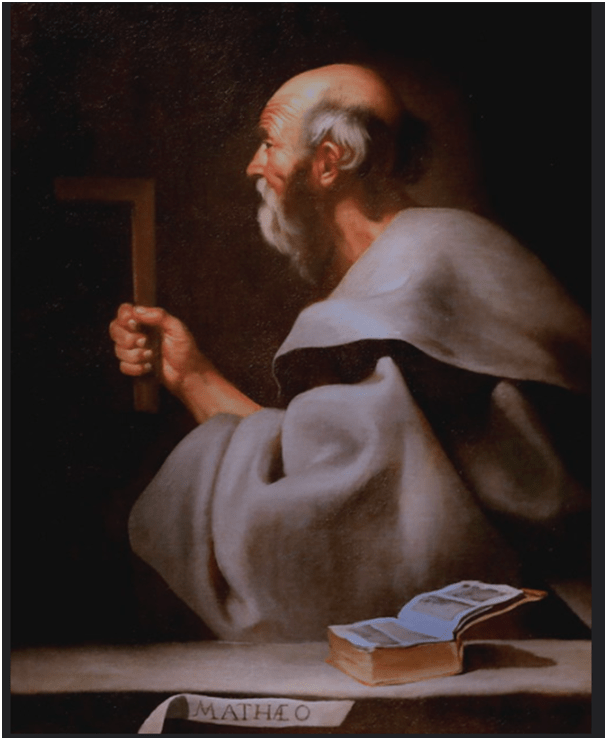

As an example of a root in Velazquez’s of this particularly Spanish, in Ellis’s view, devotional speciality Dury & Kientz use Ribera’s early painting of St. Matthew, as reproduced here.

According to Xavier Bray in 2009 the realism of such iconic paintings was less to do with Caravaggio, whom they certainly admired and emulated, but through ‘access to an art form that was exceptionally real in its very nature and part of their own religious and cultural heritage: painted wooden sculptures’.[10] The standards thus set up for painting were in the form of an emulative paragone with Church sculpture in which setting and figure would emphasise trompe l’oeil three-dimensionality. Thus the precepts of the Council of Trent might be realised that the sacred is declared real and thus the real is effectively equally sacralised. The Spanish Gallery has aimed to focus on the traditions of the Spanish ecclesiastical polychrome sculpture in setting (in the Banking Hall for instance and its lighting) to, in particular emphasise the transition and continuing exchanges between sculpture and painting united in a tradition of patterns of multiple colours in effective real conditions where the transition between light and dark is emphasised. Hence chiaroscuro or ‘tenebrism’ in Spain is not just a fine technique of Caravaggio’s. It is the essence of realising inner emotion, indeed ‘passion’ in its full sense, in the external world – somewhere between dream vision and everyday reality.

Ribera’s Saint Matthew is precisely a figural paragone with sculpture wherein the fullness of the folds of Matthew’s robes confront a two-dimensional frame, an example of which he holds in his hand – a ‘set square’ – in order for one to mock the other and emphasise the liminality between real, visionary and sacred before us. The standards of this art, in Zurbarán and Ribalta, as well as Ribera, is to ensure the viewer felt proximate in time, space and feeling to the figures which seem to press onto the surface of the painting and sometimes lean out of it, an effect of great moment in which a ‘real presence’ of the sacred is detected. Effects of flesh – and folds in skin, the palpitation of blood vessel and muscle for instance, as well as cloth, were hence valued for their haptic potential (even in but not exclusively young flesh as in Murillo’s Ecce Homo, previously mentioned in this series). Tears and palpable droplets of blood were the guarantor of the sacred made flesh but paradoxically requiring extremes of artifice. Notice, for instance, how blood droplets seem to ooze from the surface of El Greco’s Christ on the Cross in Bishop Auckland, and not just on flesh but from the surface of the painting. Xavier Bray speculates that the reason that painting won the contest between it and sculpture for the foremost devotional art was that painters could emphasise that the effects of the real were the product of art and therefore not of a thing that can be idolised in itself but only used as a means to pass through to the true sacred subject, in line with the demands of the Council of Trent.[11]

The date of the Saint Francis in the Spanish Gallery makes it roughly in the same domain as the Saint Matthew. It shows the same trait of impressing the figure through the picture level of its frame by posing it in such tension that the hand of the saint seems bodily to touch the frame of the picture attempting to contain it on the viewer’s left. Indeed here is a good place to look at it and some of its details in fragments:

Everything in this painting strains to embody two dimensions in an illusory three dimensions, including the use of light and shadow. Indeed the painting interests me in part because its representation of the visionary glory of God in the extreme right top corner as a dull ochre patch that reveals divinity only in its reflection on the torso of this young and very attractive man. That flesh includes those living wounds of the stigmata on his hands, which indicate that Francis is another man whose surface skin has been penetrated by vision. The hand on the left appears to project out into the viewer’s space with an open gesture that is both vulnerable and companionable – this young man is taking the viewer on a journey with him.

The skull as a symbol of mortality seems dominated by the life inside Saint Francis, into which interior we are invited by open hand, wide eyes and slightly parted lips. Flesh in such paintings is ambiguous. It is not the mere withering grass that the skull and flesh scourge on the table portend as the table itself hold back the most part of his body from the surface of the painting, but something God transformed into the sacred by making his Word flesh in Christ. The latter’s cross projects out from the surface too to emphasise why the blood in Francis’s stigmata is painted as living and flowing rather than healed. The curves and folds of Francis’ habit far from being entirely ascetic seem to fall in ways to release the beautiful flesh tones of the paint at Francis’ neck and the curvature formed in his skin by the man of muscle and working viscera, even that lovely larynx so visible to eye and almost to touch as well.

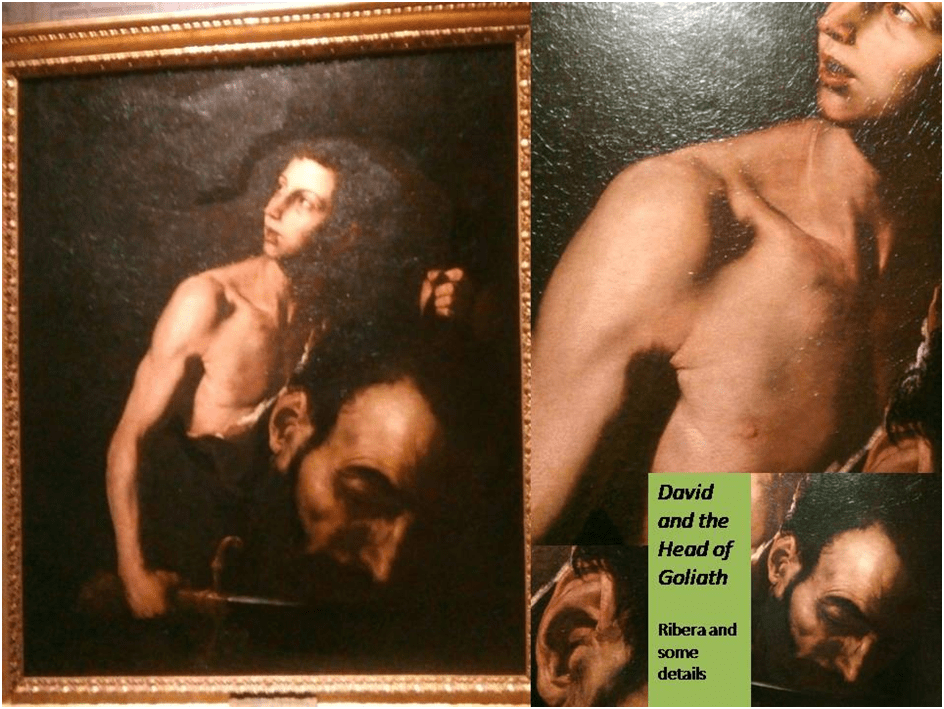

Nearer to Ribera’s ‘art of violence’, a term proposed by the Dulwich Gallery’s selection from Ribera in their 2018 exhibition is the remarkable David with the Head of Goliath. Yet before committing myself to this comment I compared Ribera’s painting to that of Caravaggio which it emulates. That emulation is contextually appropriate is perhaps confirmed by the fact that ‘Carducho exalts the collections of the Count of Villamediana, Juan de Tassis, who, as Mayor for Naples’, acquired a Caravaggio David and the Head of Goliath, that one he painted in 1607 and now in the Kunthistoriches Museum in Vienna.[12] Comparison of this prize with Ribera’s 1620 version reveals a lot about a difference of approach to conceptions of the meaning of Old Testament figures in Baroque Italy and Spain comparatively. It is a worthy comparison because of the likelihood of Ribera knowing directly of this version.

There are major differences in the figures here and in the employment of space, including the illusion of a third dimension, including that notional space into which objects might apparently project themselves in between the pictures apparent surface level and the viewer. Ribera here so masters the torsion of his figures that the twist of the severed head of Goliath appears to twist the forehead out of the picture surface. Of course such effects are subjective because illusory. But whilst Caravaggio’s David fronts an imagined spectator on the viewer’s right, Ribera’s twists to the left as if surprised by a voice he was not expecting (perhaps that of God himself), and which relaxes his posture and his sword, that which he had beheaded the giant head presented, so that it isn’t evidently that of a young lad playing the military man, proudly bearing the tools and spoils of bloody war but of a youth surprised again to see that he is still a boy. The flesh of Ribera’s David is also more relaxed and more boyish than that of Caravaggio who continues to play at the masculine hero in front presumably of King Saul to whom he presents the head of the Philistine champion. The flesh on Ribera’s youth is more real and less a thing of collected perfect fragments of male pulchritude – even a comparison of the displayed nipple of the boy points to the reality of flesh that invites haptic response.

Likewise this is flesh clothed in skin that is moulded around a yet undeveloped male body. Hence the skin is folded and plastic still unlike that wrinkled in the aged head of Goliath. Neither figure’s face is in a position to gaze at the viewer of the painting in Ribera unlike Caravaggio. Goliath’s head, rather than affronting us with its pride in his size and strength but made to bow to greater power. Indeed, it is not the power of David, type of the King-to-be of Israel we see here, but the type of Christ, which David was to the Christian Church in its typological readings of Old Testament figures. I see not violence in Ribera but infinite tenderness about the condition of the mortal confronting the infinite and immortal. No gore drips from the heads’ severed connection to the body. Rather Goliath mourns his lost body that has not served him as proudly as he served it.

My reading here serves to support Ellis’ view that Ribera took the violence out, to some extent, of the raw mortality of Caravaggio’s figures and made it instinct with the interiority implied by figures hearing a new message. This painting valorises both hearing and ears – goliath’s huge ear providing access to the dark cave of his regret. We might emphasise this again by looking at how Ribera’s pupil, Giordano, dealt with his master’s subject in a work of unashamed emulation now owned by the Spanish Gallery.

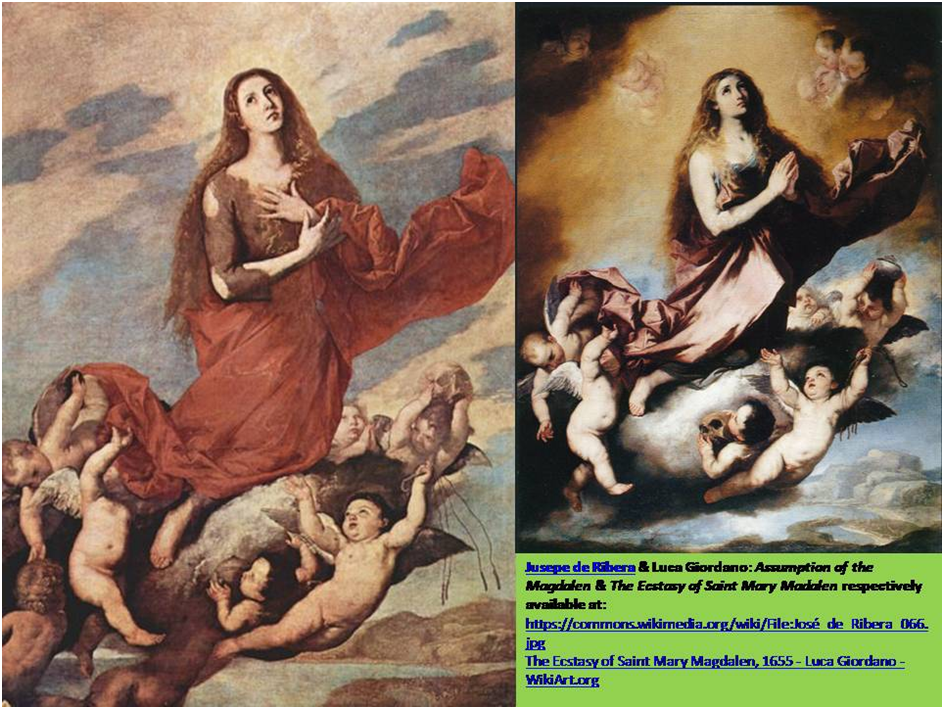

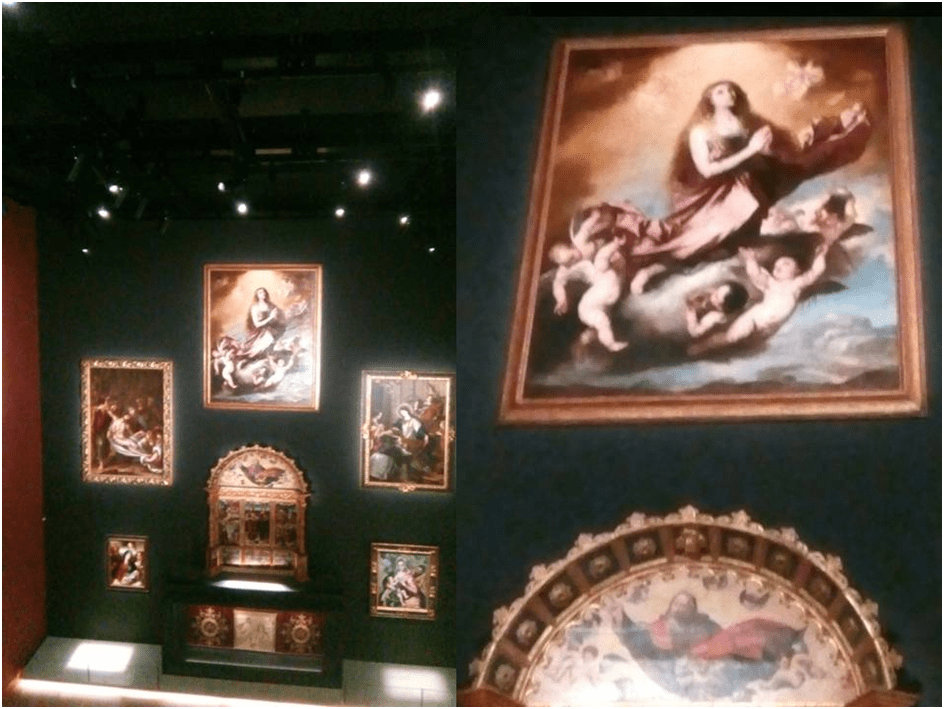

Neither painting is a favourite of mine but there is no doubt that Ribera’s ‘original’ does not seek to prettify or etherealise the saint and recalls through her red cloak her role as a mortal – that of a prostitute in poverty. Ribera does not show the hands in prayer position but placed as an expression of an inner passion. Whilst Giordano provides a numinous upper visionary light with a Gloria of baby angels Ribera expresses a woman who still feels too weighty to be thus lifted. Nevertheless the Giordano does honour the master and is brilliantly placed in the East Wall of the Banking Hall of the Spanish Gallery.

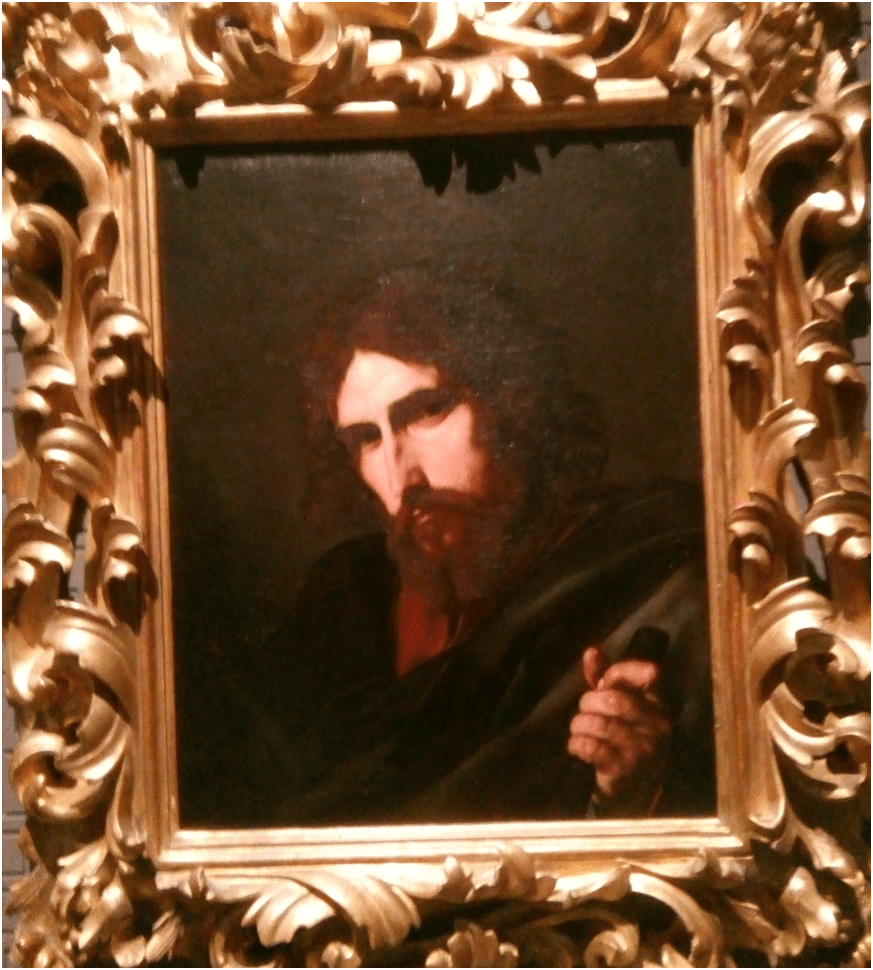

I pass over the painting of Saint James the Giver because I can think of nothing to say of this apostolic painting but here it is.

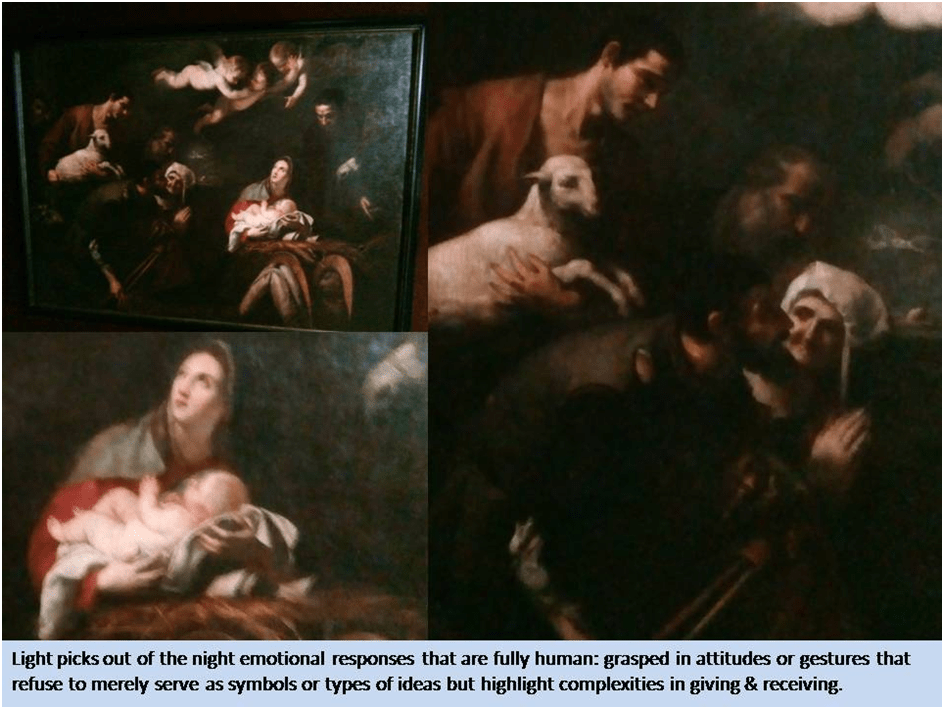

However, it is impossible to do the same with another painting though its placement in the Gallery irks me rather, being in the shadow of the balcony on the South Wall of the Banking Hall, where even from the balcony it is difficult to get a comfortable view of this late great painting where Scholz-Hänsel sees a deliberate return to ‘tenebrism’. He argues that this late return is not as a mere ‘flag-bearer to chiaroscuro’ but as, in the words of Mayer, the “prophet of new light”.[13] Indeed it is the sheen of light that characterise the David and Francis that we have already discussed.

I find this painting moving in precisely the ways Ellis suggests however sentimental such judgements now seem. Light picks out of the night emotional responses that are fully human: grasped in attitudes or gestures that refuse to merely serve as symbols or types of ideas but highlight complexities in giving & receiving. The mother’s eyes protect her child not only from intrusion but also divinity, as she half scans the adoration directed at her from both the shepherds and the cherubs. The older woman to the Virgin’s left gazes in amazement at the sudden and perhaps unexpected eloquence of one of the shepherds, whilst another such above him cradles the lamb offered to Christ as sacrifice much as the mother cradles her child. Already Mary seems to reject the sacrificial pain ahead of her and her son.

I love Ribera and still believe he is not regarded as highly as he deserves but that will never be a judgement I can recommend, since I do not possess wide enough knowledge to do so or the language to assert it. But see these pictures in the Gallery. Some of them will not be there forever.

My next blog (no. 5 in this series) will be one on the subject of several paintings in the Spanish gallery. These pictures have developed my responses more richly than I could have imagined possible beforehand, that of Spanish ‘Still Life’. Hope I see someone there.

All the best

Steve

[1]Havelock Ellis, the psychologist of ‘inversion’, from his The Soul of Spain (I have it on order because only just discovered) cited in Nigel Glendinning (2010: 196) ‘The “Terrible Sublime”: Ribera in Britain and Ireland’ in Nigel Glendinning & Hilary Macartney (Eds.) Spanish Art in Britain and Ireland, 1750 – 1920: Studies in Reception Woodbridge, Tamesis 188 – 197

[2] See my blog in full available at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2019/10/31/riberas-nudes-men-penetrated-by-pain/

[3] Ibid.

[4] Michael Scholz-Hänsel (2000: 16 – 18) Jusepe de Ribera 1591 – 1652 Cologne, Könemann Verlagselschaft mbH

[5] In discussing whether works that might have influenced Velazquez were from a time when Ribera’s influences were mainly Italian, Dury and Kientz say: ‘Au contraire, trois séries de toiles sont nécessairement liées à l’Espagnes à une date plus précoce. La plus ancienne peinte par Ribera est l’ apostaldo dit aux cartels (fig. 73) qui fut trés certainement réalisé au début dus séjour romain de Ribera’. (Contentin Dury & Guillaume Kientz (2021: 86) Dans La Poussière de Seville: Sur les traces du ‘Saint Thomas’ de Velázquez Orléans, Musée des Beaux-Arts d’ Orléans).

[6] Ribera cited from a manuscript discussion with Ribera recorded by Jusepe Martínez (1602 – 1682) in Scholz-Hänsel op.cit: 9.

[7] Xavier Bray (2018: 44) ‘ Ribera: the shock of the Real’ in and Edward Payne & Xavier Bray (Eds.) Ribera: Art of Violence London, D Giles Ltd with Dulwich Picture Gallery

[8] Scholz-Hänsel op.cit: 6-11.

[9]Havelock Ellis cited in Glendinning op.cit: 196.

[10] Xavier Bray (2009: 17) ‘The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture 1600-1700’ in Xavier Bray (ed.) The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture 1600-1700 London, National Gallery Company, with Yale University Press. 15- 43

[11] Ibid: 40

[12] José Juan Pérez Preciado (2016: Location 2356) ‘Art Afficionados at Court’ in Jean Andrews, Jeremy Roe & Oliver Noble Wood (eds.) On Art and Painting: Vincente Carducho and Baroque Spain Cardiff, University of Wales Press (Kindle ed.)

[13] Scholz-Hänsel op.cit: 22

One thought on “Despite the concentration of most on the extremities of intense interpersonal but external drama and violence in Jusepe Ribera’s art, Havelock Ellis valued it in terms of its ‘essential tenderness’: saying that in the ‘power of rendering loving devotion, of tender abandonment, associated with religious emotion, Ribera not only surpasses all his countrymen, but is scarcely excelled outside Spain’. This blog reflects on works by Jusepe de Ribera (1591 – 1652) currently in the Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland. Golden Age of Spanish Painting (No.4).”