If we take drama back to its basic elements – without the clothing and properties indicative of illusions of power – then both directing and enacting Shakespearean history must understand how to create ‘men’ large enough to fulfil the expectations of the huge roles they are given to play in life and art. In those conditions binary gender systems might finally meet their match. This blog reflects on a rehearsed but performance-ready version of King Henry VI Part One screened by the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) – seen on the Durham Gala’s Screen One on 23rd March 2022.

Although the screening of the first part of Henry VI ends with the legend ‘To Be Continued’, it is a satisfying play in itself that focuses on a patriarchal power system under stress, ending with a marriage between Henry, a young boy-child king and a powerful woman already sexually compromised with the man, The Duke of Suffolk, who would court and win her ostensibly for the king but actually for himself. In this production the marriage itself – in process only at the end of the text of the play – is anticipated in a powerful image. The couple are shown immediately front of screen being showered with rose petals – white ones at first but then much more red – to remind us of the power struggles that will dog this reign and this marriage: in short the Wars of the Roses. Whilst that war is only predicted in this play, its genesis is given a legendary origin in the choice of red and white roses by the persons and family lines who will become its main protagonists. If civil dissension is already afoot in England, and resonating in France, it is represented by a dialogue between Church and State in the persons of Henry Beaufort, the Bishop of Winchester, and representative of Papal interference in English affairs (‘Rome shall remedy this’ Winchester warns Gloucester in Act 3, scene 1: l. 51), in terms of the values of the play, and the Protector of the realm during King Henry’s minority, the Duke of Gloucester.

But at the centre of the play and only anticipating that larger dissension are the endgame tactics of Henry V’s war to gain the crown of France. This struggle sets up a tense balance between powerful persons attempting to represent in battle their respective puppet kings. For the young kings of both France and England, Charles VII (Charles the Dolphin or Dauphin) and Henry VI, only son of Henry V, are presented as too young for the roles they are called upon to play and with each a tendency to an anti-heroic effeminacy, and the prey therefore of stronger men. Indeed, Gloucester says of Winchester that he and the ‘Church’ in general hate a martial hero such had Henry V had been and:

None do you like but an effeminate prince,

Whom like a schoolboy you may overawe (my italics).[1]

Having said this both Winchester and Gloucester set off to the young king precisely both to overawe and dominate him, and although the young prince oft feels he brings peace between them it is clear he neither sees he has failed nor could effectively police his intentions.

However, that the play deals centrally with mismatches between gender identity and gender expression is clear from the fact the ‘young effeminate prince’ raised to rule on each side of the Channel is represented in the French wars by a male and female warrior respectively as their avatar. Let’s start in the patriarchal spirit with the English male.

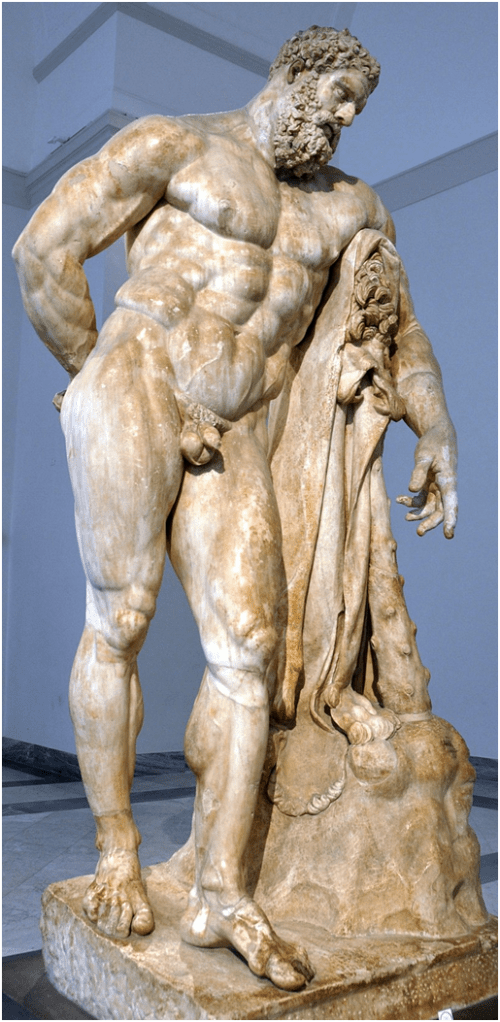

Leading the martial role in France for England is a man who would be, and is in the eyes of some but not all, the very image of a heroic warrior, Talbot. At times his name alone – the cry ‘A Talbot’ is frequent in the play – makes lesser men (or as they are known in this most nationalistic play, ‘French’ men) ‘fly leaving their clothes behind’.[2] He is cast by Sir William Lucy as ‘the great Alcides of the field’ (Alcides is better known as Heracles) after his death.[3]

Yet the play allows even Talbot to question how much a warrior’s masculinity is a matter of policy and place in an institution, including the power to command others, rather than of gender identity or personality per se. There is much boyish play with the association of masculinity with sexual as well as military prowess when Talbot is invited in to visit the Countess of Auvergne:

To visit her poor castle where she lies,

That she may boast she hath beheld the man

Whose glory fills the world with loud report.[4]

Though the word ‘lies’ is meant to be sexually ambiguous, Talbot knows it may have another meaning applied to a wily French aristocrat. She questions the analogy between Talbot and Heracles (Hercules in his Roman form now here) or the Trojan hero, Hector.

I see report is fabulous and false.

I thought to have seen some Hercules,

A second Hector for his grim aspect

And large proportion of his strong-knit limbs.

Alas, this is a child, a silly dwarf:

…[5]

It may be that women secretly see men in the flesh and in their vaunted powerful roles as much less substantial than those images of them in both reported stories and artistic images for the Countess assumes that once she possesses this image safe within her house, she has him ‘trained’ and ‘thrall to me’ like a portrait of him that already hangs in that house.[6] Talbot indeed seems to know this for a truth as much as any woman in the play, though he will disdain base women such as he sees Joan of Arc to be. For men, Talbot implies, are not their fleshly bodies however large and muscle-bound these are:

… I am but shadow of myself:

You are deceived, my substance is not here;

For what you see is but the smallest part

And least proportion of humanity.

I tell you, madam, were the whole frame here,

It is of such lofty spacious pitch

Your roof were not sufficient to contain’t.[7]

Talbot soon shows the Countess that he is not a mere maker of metaphysical riddles herein. For the single man is a ‘small part’ when we see that his true stature lies rather in the command of a sizeable ‘body’ (in another sense) of men to do his bidding for him and validate it, as if it were the self-evident truth of things. The power of warriors, the Countess will learn lies in their soldiers. Having learned this, she succumbs To Talbot and soldiers by an immediate return to a more feminine role of provider of wine and ‘cates’ for all them. In this production the soldiers encircle the Countess with pointed phallic spears that bear immediately in upon her. Their relationship to the true single warrior, he says, is to be the truth of his power as an individual strong man:

These are his substance, sinews, arms, strength,

With which he yoketh your rebellious necks,

…[8]

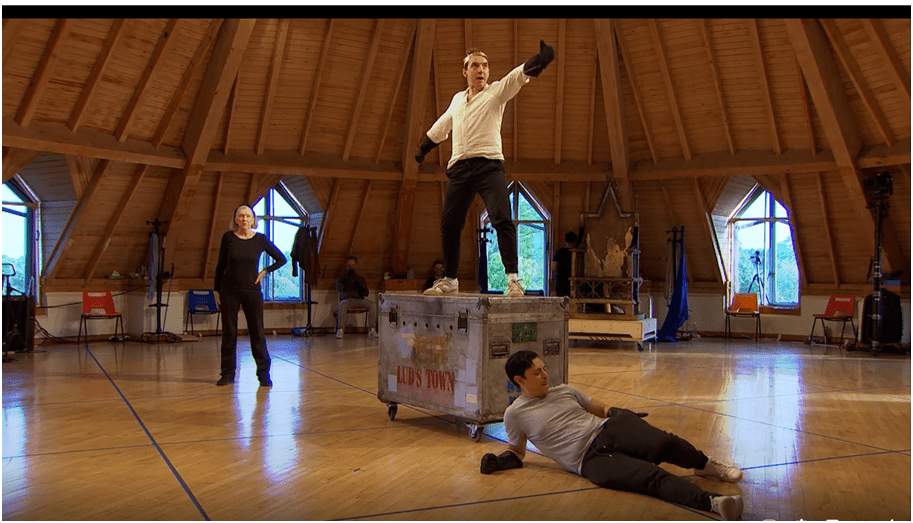

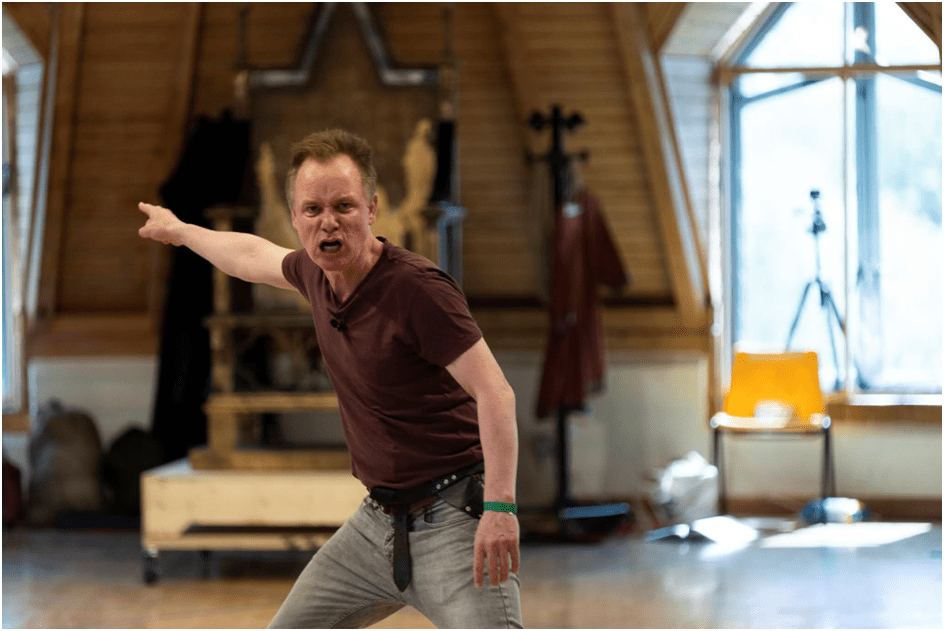

So the appearance of he who plays any man in Shakespeare’s very theatrical sense of the world is less important than his support and command of stage or scene, achieved by props, proxemics or physical stage presence achieved by artifice of performance and exterior manipulation in theatres or in the mechanics of power (weapons, armies and their logistics) in wars, statecraft and the home. This production emphasised this by the paucity of stage properties and the richness of expanding space that a rehearsal room with balconies, side entrances and ladders facilitates. Thus note that the Dolphin attained stage presence in most interesting ways, as in the characteristic scene below, where a purposively foppish and effeminate enactment by the very talented Jamie Wilkes is also given prominence and power that allows the contrary nature of patriarchy to be explored:

And the Director emphasises this more by some clever casting of powerful women in the role of powerful men, such as the Duke of Somerset (the red rose Duke), the Duke of Burgundy – ally of England until ‘bewitched’ by Joan of Arc – and Reignier, who finally abandons the Dauphin in the interests of his own county lands) and his daughter, Margaret’s marriage prospects. These men are played brilliantly by Mimî M Khayisa, Anna Leong Brophy, and Marty Cruickshank respectively. This also means that a man who in jeans and trainers does not look Herculean or martial in body shape such as Jamie Ballard, really convinces as Talbot and deepens the meanings evoked around gender expression with the power of performance and direction alone.

On the French side, a ‘fickle wavering nation’ as even the sickly boy Henry VI is allowed to call it in one of his final speeches, male authority is represented by a woman, Joan of Arc, a woman armed to the teeth. She is suggested to have the uncertain backing by some kind of supernatural practice and sexual manipulation. Talbot refuses to fight her because to him she is a mere peasant woman but Burgundy, whilst fighting with the English, plays with the cusp between gender identity, gender expression and sexual ambiguity between myths of virgin (maid) and ‘whore’.

BURGUNDY: …..

But what’s that Puzel, whom they term so pure?

TALBOT: A maid, they say.

BEDFORD: A maid? And be so martial?

BURGUNDY: Pray God she prove not masculine ere long –

If underneath the standard of the French

She carry armour, as she hath begun.[9]

This impossible role is played brilliantly by Lily Nichol in this production but it is worth reflecting that on the Elizabethan stage the ‘maid’ would be played by a man, who is here and elsewhere suggested to enacting a man in her martial role. We know Shakespeare makes conscious play of this transsexual theme elsewhere – both in tragedy (Macbeth) and comedy (As You Like It), but the point is never lost by an actor of Nichol’s skill in performing the differences between an identity and a conscious role. Thus the audience is perpetually perplexed by her until her final séance with devils. Her tragedy is that she knows that men are weak, obsessed with titles (as Talbot with his ‘silly stately style’ in titles – at least as rehearsed by Sir William Lucy) and obsession with their supposed consistency of character. When the Duke of York says that it seems ‘as if with Circe, she would change my shape’, she retorts ‘changed to a worser shape thou canst not be’.[10] Her success in changing men’s minds by seductive flattery means that she know men are already lacking in that which they prize but that they hide the fact from themselves: Of Burgundy she slyly says on his exit once he has turned against England: ‘Done like a Frenchman: turn and turn again’.[11]

So what of the significance of this production of this play? I would say that it emphasises the self-referential and provisional in Shakespeare’s attempt to grasp the nature of how insight and imagination (beginning to take the form of a sorcery theme that will not be fully developed until The Tempest) interact with sexual and national and international politics, such that we stop thinking about these things as based in a natural or biological order. For power works only when it is seized and not when it relies on tedious arguments from genetics such as those of the dying Edward Mortimer in Act 2, Scene 4. Henry VII will like Henry IV and Henry V be a Machiavellian power politician, owing nothing to Mortimer’s dying blessing but the seed of an idea that the world is open to manipulation so that he too could take a crack at playing King and top man. Men are weak until they know and have the experience not to be driven merely by old-fashioned ideas about inherited virtue. Talbot’s son may inherit from his father the will to die like a man, but his father in fact knows that he dies instead like a woman in a patriarchal violent society – raped by superior cunning rather than legitimate military honour. These lines still surprise us don’t they, where the father characterises his son’s murderer in war as if he were a rival lover:

That ireful bastard Orleans, that drew blood

From thee, my boy, and had the maidenhood

Of thy first fight, …

If sons die like maids, they are fulfilled only in their father’s ‘old arms’ that enact a grave, not in something achieved and enduring. This is an interesting broken play and this production brings more out of it than I have ever before encountered in another. I don’t pretend though that I have clarified anything even if the production actually does do so. Maybe that is not anyway what is required? What we need is a way of finding why certain works endure as this one does, whilst failing to convince anyone that it is because it is a great and undoubtable work of art on its own.

All the best

Steve

[1] Henry VI (1) Act 1 Sc. 1, lls. 35f.

[2][2] Ibid: Act 2, Scene 1. Stage direction between lls, 77f.

[3] Ibid: Act 4 Sc. 4, l.172.

[4] Ibid: Act 2 Scene 2: lls. 41ff.

[5] Ibid: Act 2, Scene 3, lls. 17ff.

[6] Ibid: lls 33ff.

[7] Ibid: lls. 49ff.

[8] Ibid: lls. 62ff.

[9] Ibid: Act 2, Scene 1: lls 20ff. Note:’ Lord Talbot calls her “puzel” rather than Pucelle; “puzel” being an old English term for a promiscuous woman’. (Joan of Arc: A Hero or a Villian? | Utah Shakespeare Festival (bard.org)) The term ‘pucelle’ could mean maid or virgin.

[10] Ibid: Act 5, Scene 1, l. 1.184, Act 5 Scene 2, ll. 56ff. respectively

[11] Ibid: Act 3, Sc. 3, l. 85.