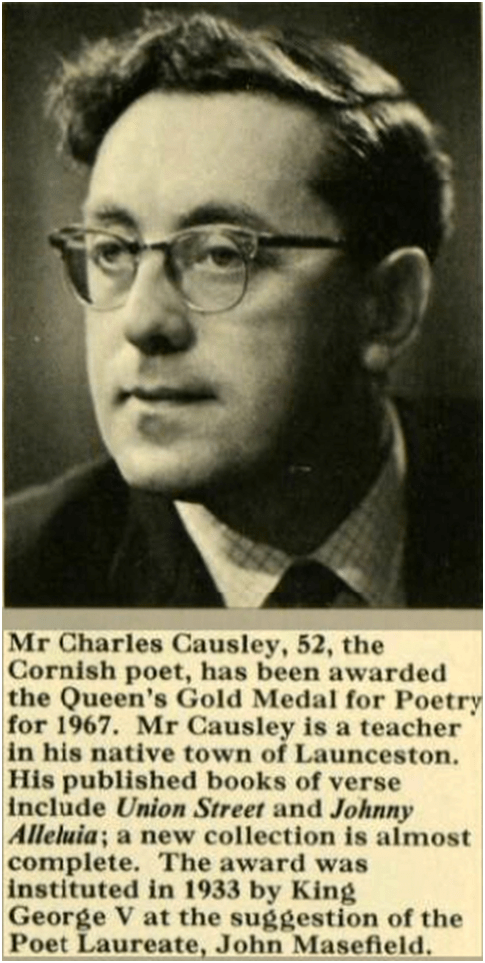

‘ I’d only say someone was gay if I feel they’re comfortable with who they are. The sadness is I don’t think he [Charles Causley] was ever comfortable with who he was’.[1] This blog reflects on a brilliantly intelligent novel on, it argues, the definition of ‘being gay’: Patrick Gale’s Mother’s Boy (2022) London, Headline Publishing Group.

I love Patrick Gale’s novels and I suppose it is best to come clean by saying of this one that I admire it as a brilliant analytic statement about the theorisation of gay ‘identity’ rather than love it. In fact I think the book is far too intelligent to have much truck with simple statements of identity or of aetiologies of identity. It’s title is a classic aetiological statement of identity: ‘mother’s boy’. As a boy I came across a version of this which said: ‘My mother made me a homosexual’. The only saving grace to the harm this aetiological myth created was the riposte that always lives with it: ‘Oh! If I gave her the wool, would she make me one too’?

Yet this notion was more offensive to women than it was to gay men: a complex way of binding women both to notions of their responsibilities to a role to which men put the limits and which, in particular, targeted dominant women. This novel, the true key character of which is Laura – a lady who takes in dirty linen and returns washed laundry. She builds on that occupation a theory that the cause of ‘stains’ is not a problem or worthy of distinction since knowing how to remove any stain is more important than dwelling on its cause. Of course I have made this wordier than would she. She merely shows that removing the stain from communion wine from an altar cloth can be done in the same tub with the same implements as semen stains on the sheets of a boarding house with a poor reputation. That boarding house by the way is peopled with the unacknowledged sons of the male burghers of the community of Launceston and their lone unmarried mother. She is dependent on any income coming her way; another undoubted hero in this novel otherwise made up of men who fail to assert themselves, or their desires, or do so shabbily and in secret.

I take my title from a pre-publication interview with Gale in which strangely enough Gale takes the time to talk about his acknowledgement to Kate Clanchy. Clanchy has probably drawn less attention and empathy than J.K. Rowling whilst being considerably better intentioned and less ideological and so it is generous of Gale to do this whilst reminding Clanchy that combative defensiveness such as hers, that refuses to contemplate that unintended errors of descriptive generalisation can still cause damage and stereotype despite the fact that she will never accede to making these errors.

Indeed she continues to utilise the subjects (and perhaps ‘victims’) of that peon to her own virtues Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me to defend her, as if she remained the main issue of the book, which is perhaps unfortunately true of its tendency. Nowhere has the hubris of teachers been so misdirected in public.[2] This digression into a literary row rapidly being forgotten barely matters except that it further emphasises that writers have responsibility to truth over flagging their own virtue and insistence on being right. For Patrick Gale couldn’t be further than doing this.

This book more than any other I have read refuses to accept that being gay is anything other than a chosen not a given identity; which is not to say that men who love men might do so because of some kind of reason or aetiology in their genetic or developmental inheritance but that this reason will not be the same for all of those people nor should it constitute an identity lest they will it and accept its relational reinforcement by others. Indeed the same is true of heterosexual attraction. There is a finely intelligent example of this, expressed precisely and analytically and quite brilliantly in this novel. Walking home through Main Street on the rock of Gibraltar in 1942 with an attractive woman called Rusty, to save her from unwanted attention from other men, Charles still ‘felt the massed male attention on him as much as her, or felt the stares pass through him to get at her’. But Charles learns from this much about the aetiology of such expressed and unexpressed but sensed desire, or what seems like desire but may just be a socially generated force. “Try me on for size”, say some men to Rusty in his hearing but:

It struck Charles the men didn’t really expect her to respond – if they had, they might have been at a loss. Rather it was as though they needed to signal to each other that she was what they really wanted, that the company of men was always second best. It was an assertion of polarity as much as of desire.[3]

Not only is this intelligent – on behalf of both the imagined Charles Causley and Gale, for who the former is an avatar here – it relates to the novel’s structure and themes. For this novel contains so much about of the learning of code – whether those codes be languages, dialects, Morse code, flags, coding from manuals. It also concerns the consequences of being able to understand such codes or not. Yet all Gale says here is something about how groups ‘needed to signal to each other’ to confirm something about themselves to others and perhaps even confirm it to themselves. Here the coded message is that of heteronormativity. Brilliant, isn’t it? And, at the end, I will perhaps it is not irrelevant to the issue of virtue signalling and the ways it can disrupt a politics of legitimate identity signalling (hence the digression on Clanchy), about which I suspect Gale is also wise.

In his war-time training Charles is ‘introduced to code books’.[4] Code is at the heart of this novel I think. Charles, the eponymous hero, can be read by few whilst others signal messages about themselves to each other furiously, often to contradictory effect. Charles sometimes uses his supposed special knowledge of enclosed domains, including codes of secrecy in military behaviour, to silence others or convince them of their ignorance. For instance, he does this, quite without concern to her feelings, to his mother, who is ‘genuinely baffled’ about why some military men may be receiving harsh sentences when ‘Nobody was hurt’. To which Charles say: “Mother, if you really don’t understand,…, I am the very last person who’s going to explain it to you’. The analysis of the effect of these words is precise and shows how codes and their possession by a few give rise to assertions of superiority by that few that never need to be acknowledge or justified:

He hadn’t sworn, which he sometimes did, like the sailor he had been, when something truly angered him. But the tone he used had been withering in a way that frightened her into an awkward silence, … [5]

It takes but a moment’s reflection to see that this is how Charles, and perhaps other men who have sex with, or even love, men, silence others whose speculation about them they feel to be harmful to them. It is what Charles very cruelly does to Cushty, that sailor whose name is a description of the kind of life Charles might expect to live with Cushty. But this life he altogether rejects, although we only hear a coded version of that discussion from another room, with the radio on, through the consciousness of Laura who only half understands the codes employed (‘Were they arguing?’). That Laura does not understand the codes that might give access to Charlie’s inner life as a man who loves men is ensured by Charles’ own secrecy and denial of other alternatives to pursuing poetry and ‘single’ life with his mother. And Charles misuses male power here, I think Gale allows us to see, and, far from being kept from love of others by his mother, keeps her being freed from caring for him alone. He becomes the avatar of the other Charlie, who monopolised Laura’s care, his disabled war-wounded father. My own feeling you see is that, if this book has a hero, it is Laura.

But let’s stay with Charles Causley a while, for ostensibly this book is his. No-one could look less likely to be the hero of a story than Causley as he appeared in public though this book certainly shows his exposure to the fearsome perils of war at sea.

But otherwise Charles’ life is one with very little incident – so much so that he seems to court such a life, coming across sexual or romantic adventure almost by chance and to minimal consequence. Even the stanza chosen for the books epigram (from ‘Never Take Sweets from a Stranger’) is about the fear of inviting even the most tiny of intrusions into one’s life: especially it seems the sensual (or sexual) and fleshly type:

Watch your hurt heart when it wavers,

Keep your clay cool on the shelf.

Avoid other flesh and its flavours.

Keep yourself to yourself

When Charles spends the night with a man first, as far as we know, it is a matter based on a series of accidents. The only relationship we see with any duration, although we may infer there is much that is not said or shared, it is with an ex-public school naval officer revisiting his fascination with other boy’s, and his own, bodies in the willed and welcome absence of female company. That relationship endures though only until such a point as this man will marry for the sake of his career and reputation. This second man is odious but the first is not – and the first’s comfortable sweetness (he is Cushty by nickname as well as nature) serves as a foil to show the awful cruel terror that Causley awakes in others to avoid commitment and definition by desire.

Of course we are to understand that Charles sees his first duty as that to his mother but it is also clear that he uses this to excuse himself from development into a full human being. Refusing warmth, he chooses terrified anger, and, in doing so, thus denies his mother the chance of like development. Laura could and might have developed. There is more warmth in her for more people than Charles ever feels, and the novel beautifully signals her felt need to grow away from always being someone’s carer. But this cannot happen, despite the fact that many people – men, women and children – are candidates to share her life if she was allowed to commit beyond Charles. Charles is a kind of fantastical beast guarding the treasure of the heteronormative, using the fact that his mother cannot be his sexual partner to make her an ideal wife for a man (himself) who wants life to pass him by, or appear so. Eventually, Laura realises ‘he had, in effect, made her the kind of wife she had never been able to be for Charlie, whose work was entirely for her loved ones: cleaning, shopping, cooking, ironing and the rest’.

It is clear from hints she passes (“But shouldn’t you be saving? … For when you want to settle down?”) it is not her that holds Charles back from development but him holding Laura back (“I am settled, or as settled as I’ll ever be”). Charles, in my book, is barely likeable by the end of the novel. Earlier he has his moments when he opens his heart – if only a little.

This is a fascinating book. Read it. There is that in it that resists being the enjoyable and likeable read of early novels with a kind of queer bildungsroman theme of this lovely author like Rough Music – Charles is not likeable and he exists to analyse the true effects of the grinding fear of that which cannot be coded in normative fashion. That means story is more like life, ultimately unsatisfying, and less amenable to evoking pleasure for a reader. But it is a very good book.

All the best

[1] Patrick Gale in an interview with Susie Mesure (2022: 46) in ‘Author’s Tale’ in the i (26 – 27 February 2022)

[2] I did by the way once admire Clanchy as this blog shows: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2019/11/12/reading-kate-clanchy/ . There is a very level headed statement of the issues here: https://www.newstatesman.com/comment/2022/01/what-kate-clanchys-treatment-can-teach-us-about-racism

[3] Patrick Gale’s Mother’s Boy (2022: 259f.) London, Headline Publishing Group.

[4] Ibid: 221

[5] Ibid: 387