‘a formidably intelligent and well-acted prison movie and also a love story – or perhaps a paradoxically platonic bromance, stretching from the end of the second world war to the moon landing.’ (Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian 9 March 2022 [online]). This blog reflects on Sebastian Meise’s Great Freedom [Grosse Freiheit] (based on seeing it for the first time on 12th March 2022 at the Roxy Screen, Tyneside Cinema, Newcastle).

Sometimes a film poster is a precise description of at least a part of what a great film as to offer. This is the case with this stunning example, which indicates the power of two tropes in the film. One the gestural power of heads lowered and looking away and below the eyes that confront them, in diffidence, fear, suspicion or evasion of a returned look. Surveillance is something that we do with discomfort either because we want to deny our interest in another that it might show or to deny our awareness of their interest and gaze on us. It happens we shall see, not only where there is a threat from others in prison, for any number of reasons – one of which may be sexual interest. Another is in a cottage – a public toilet used for purposes of sexual meeting and behaviour. In each case this behaviour is not based on the identification of a person as gay or queer but on their availability in the moment or for a specific contracted purpose of certain duration.

The second motif is the frame through which we see what we can. That is to say that the scene available for vision is only as large as the frame through which we look at it allows to us to see. The frame imposes its own limits and focal quality on what is visible. These portals for vision are often institutional spy holes, such as that affording a view of a prisoner inside a cell, or the one shown above (in the poster) which is a larger portal within the door used for the purpose of passing food. Of course their purpose is often stretched and Victor’s first sexual congress with Hans, whom is requested to relieve Viktor’s sexual distress and frustration is one such case. It is almost as if this obstruction and limitation on the sex act shown is one with the mediating effect on the act of Viktor’s aggressive belief in his own heteronormativity and admitted homophobia. Hans performs oral sex on Victor through this large glory hole which the camera sees from the private space in the cell behind Hans’ head thus occluding, but for a brief glimpse, Victor’s penis from the spectator’s gaze. The wonderful poster makes a collage of the idea of different frames of vision so that it can show a portal within a portal together with transgressive graphics showing a passage between two levels of focus at each portal. One portal has become the entry to Hans’ head as he leans to look through a prison door spyhole.

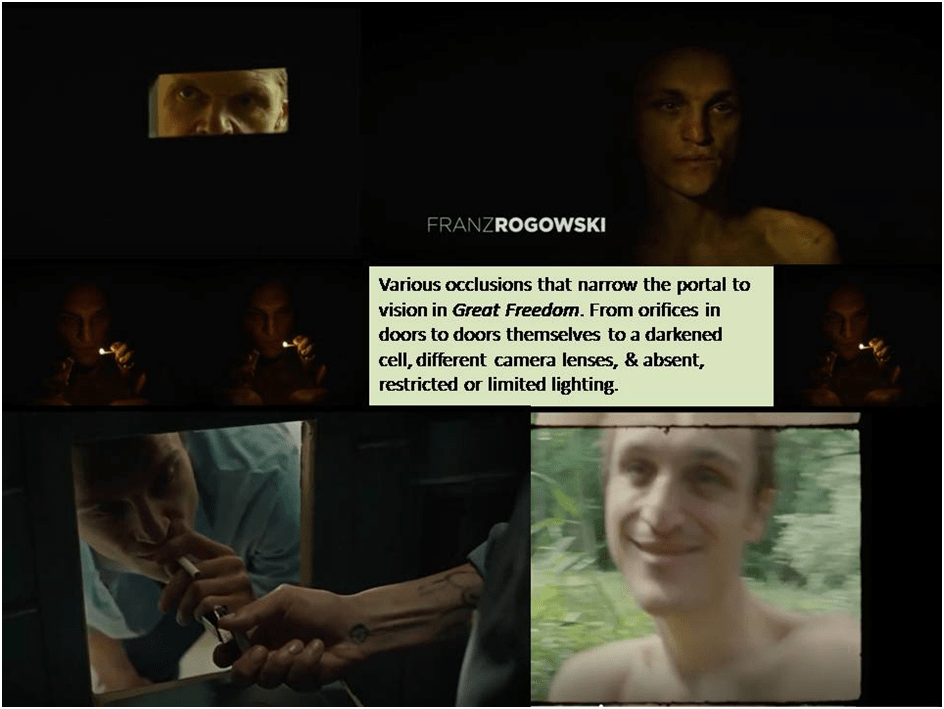

My collage above shows a number of these varied ‘portals of vision’. Such portals include the angle and focus of vision itself given by a film-camera and the film includes at least two kinds of such film flickeringly shot on a Super 8 camera. One is a holiday cine film showing Hans with a boyfriend met in prison. It is the only vision we get of him out of prison until the film’s ironic denouement. At other times the camera follows Hans into an isolation cell into which he is thrown into ‘darkness visible’ as it were, where we will see him only by a match he lights,. Those are matches that Viktor has had smuggled to him. Elsewhere we see him in the blinking light of the opening door at the end of his isolation (one such scene is used brilliantly in the trailer to the accompanying the ‘credit’ of the main actor’s name – Franz Rogowski.

The most telling framed portal turns out to be the Super-8 film shown in the film’s opening showing a series of sexual encounters between Hans and men in the urinals and off-stage in the cubicle of the cottage. At one point Hans smiles into the frame, which in truth he thinks is a mirror. For it is only clear that this film is the evidence for the prosecution in his trial under Paragraph 175 of the German Penal Code, a draconian law toughened very considerably by the Nazis and not repealed on their demise, and not eased in its severity until 1969 in fact, even by the victorious Allied occupying powers. We see the Super 8 film being fed in the camera for the judges before the summary of the case. By this Super-8 film then, Hans has been framed (entrapped indeed) by law and policing practice. However although at a lesser cost, queer relationships are always framed in ways that may or not be appropriate by other ways than just the law, as I will look at later, in relation to Peter Bradshaw’s comments cited in my title.

Sometimes the occlusion of vision in the film is caused by the physical limits of the set and the film is shot ‘entirely in a former East German prison’. Sebastian Miese, interviewed by Ryan Gilbey for The Guardian talked about that prison setting in an interesting way with respect to the treatment of partial and limited frames of vision, saying:

A studio would have been more comfortable but, on the other hand, limitations are good. You don’t have too many options for where to put the camera, or what to point it at, and that gives room for creativity.[1]

There is an analogy here between this perception about the pragmatics of filming and the themes of the film. On the one hand, it suggests that greater creative freedom is a product of ‘limitations’ in space because it forces the human responses of a film director into more inventive and meaningful ways of responding than a supposedly freer choice in a more ‘comfortable’ type of space would. On the other hand, Hans Hoffman (played by the amazing Franz Rogowski), imprisoned in a concentration camp by the Nazis and staying there under the legal framework of Paragraph 175, finds more creative ways of loving in prison than in the world freed up by greater freedoms under commodity capitalism. These points reinforce two perceptions I had whilst watching this film. First, that queer art requires even more than normative art to question the use of not only stereotypes of identity but also stereotypical norms of expected behaviour of all people involved in any human act or series of acts in varied situations. Second that no assumptions be made about the aetiology of behaviours by rooting them in notions of freedom of choice alone, since for queer people such freedoms are constantly provisional on the frameworks chosen by people other than themselves; sometimes including other queer people but not only those.

Peter Bradshaw reviewing the film on Wednesday 9th March in The Guardian (online) creates frames around queer relationships even when he thinks he is using language loosely and flexibly. The film is either a ‘love story’ or ‘perhaps a paradoxically platonic bromance’.[2] The binaries work less well here than other binaries that bedevil the construction of relationships. Are relationship between men either a matter of love or ‘platonic bromance’ and where does sex fit in either summary category since we know sex does occur (we see it in an occluded way) and does it change the nature of these categories? These categories are more than inadequate frameworks to deal with relationships of love between men that only pretend to deal with the fact that sex sometimes enters into those relationships irrespective of questions of identity on either side.

After all the problem for Viktor is that he needs sex whilst in prison and thinks Hans might be a convenient provider of that sex, even though he himself wonders at first how much this commits him to typifying their relationship – as love or ‘bromance’. Viktor never finds the words in fact. In prison he does not need to; whereas he might once out of prison. Hans knows about sex and knows he can deliver it but he wants love and looks for it everywhere, with no contradiction to the sex he might also provide for others. He performs acts of selfless love (or agape as we might call it) for men in prisons many times which backfire on him. He receives love perhaps most tellingly and unexpectedly from the long-in-the-winning empathy of Viktor for his loss of yet another lover (an accident, criminal or suicidal fall from the prison roof). All of these relationships matter in this film because love opens up multiple possibilities. The only ones that do not matter take place in a gay nightclub named in neon across our screens ‘Grosse Freiheit (Great Freedom)’, which Bradshaw rather charmingly calls a ‘Fassbinder-ish gay bar in this film with a dungeon-style sex club beneath’: in fact the prison-like cellars are a common feature of bars of that time (1969) and have nothing to do with film directors as such – alive or dead.[3]

Of course I will have to see this film again. One feature of it makes it difficult always to keep grasp of the sequence of its narrative. It sees time ironically. For instance in the shot below Hans and Viktor are watching the moon landing in 1969 but learn about the change in Paragraph 1975 in the same year totally accidentally.

The shifts from the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s happen sometimes in very unclear transitional scenes often taking place at the times when Hans is locked (as is the audience) in a black screen in part representing his cruel unlit isolation cell. We lose the sense of sequence of other lovers and their aging in Hans’s case and the sequence of Viktor’s transformation into a dependence on drugs. Our slight confusion as audience is necessary to Miese. But if confusion it is; it is a continually fascinated and enchanted confusion. To Gilbey, Miese says:

Han’s life is like a prison. … That’s how we arrived at our structure. We wanted to create this feeling that he is trapped in a time loop. Every time he goes back into solitary confinement, in the darkness, he is then spat out somewhere else.[4]

This is the most intelligent and moving film you are likely to see for a long time. Do see it.

All the best

Steve

[1] Ryan Gilbey (2022) ‘The prisoner of sex’ in The Guardian Monday 14th March 2022. Available at ‘On the same level as the Nazis’: the film about Germany’s post-war persecution of gay men | Film | The Guardian

[2] Peter Bradshaw (2022) Great Freedom review in The Guardian (online) (Wednesday 9th March) Available at: Great Freedom — Sebastian Meise – In Review Online

[3] Ibid.

[4] Gilbey op.cit.