Hockney’s life-long challenge to the facilitation by the Art Establishment of the ‘puritanical, abstract and conceptual’ is just one of the ways that he has wished to move the focus of the stories we tell to characterise modern art. This blog looks at different ways in which a ‘moving focus’ was an apt way to describe Hockney’s career as an artist who defended the role of making ‘pictures’ as the basic role of an art that challenges and queers normative thinking. It reflects Helen Little’s (ed.) wonderful 2021 book David Hockney: Moving Focus: Works from the Tate Collection London, Tate Publishing.

For my other blogs which touch upon Hockney, try the following longer pieces:

The negative impact of the frenetic move to relegate ‘narrative figuration to an inferior and provincial status’ or consign it ‘to the lowly designation of mere “illustration”’ was perhaps more obvious and much earlier in history to queer representational artists in the USA such as Paul Cadmus than it was in Britain.[1] However to an artist who looked out beyond the ranges of a confining provincialism in Bradford and to the stultifying joyless feel of a London where the Tate Gallery acquisition policy in the 1970s made ‘representation’ a dirty word in art, it was just as disabling. My focus here is why this should be so for queer art. In the USA the reason was more obvious. Ellenzweig, whom I have already cited says that the differences between schools of art were often observable in terms of stances of aggressive heteronormativity set against a group of artists who evidently did not fit in with that norm. He says that there ‘was an absolute division between gay or figurative bisexual painters and the emerging Abstract Expressionists, whose almost exclusively heterosexual male bastion became known as the New York School’. This would seem partly an effect of historical contingencies that were in part accidental were it not for the dependence of an emerging queer politics on notions of the embodied person and necessary stories of ‘coming out’ from some kind of imprisoning hidden space. And it is in this context it matters to for British queer artists. It is put well by the art historian James Saslow, as cited by Ellenzweig:

The triumph of abstract art set back gay expression by rigorously excluding any narrative subject … Art was to be about art, nothing else, and would lay bare mythic, universal human feelings through the sheer evocative impact of form and color (sic.).[2]

Hence, I think we can see how and why this apparently fragmented book, with at least three major themes covered by its title and with many diverse voices of different kinds, including poets and prose writers can have coherence, that still leaves room for non-consensual difference, around the interactions between themes and writers. We can start by listing the themes but without any pretence that this constitutes an exclusive list:

- The focus of art and The Tate as the major national collector of modern visual art moves from reliance on formal modernist abstraction.

- Visual art moves from focus on the visual surface of the canvas to include again what had been thought of as literary contamination involved in the uses of narrative and figures or ‘characters’.

- The focus of art moves from the self-referential consensus and norms in theory, that speak about art itself to the representation of diverse public and private voices, methods and styles that represent the dynamics of shifting and previously marginalised psychosocial histories.

- In a shift from the dominant model of the notion of the camera (or camera obscura) as providing the metaphor of ‘focus’ in art, the focus of even figurative and landscape art involves a shift away from the notion of a unified point of view and perspective that approaches one visual ‘vanishing point’. It moves towards the notion of multiple perspectives (and multiple foci of attention) in art, derived partly from Oriental models.

- The move of focus of models of politics that was consensual and centred on the hegemonic values of the West and North of the globe to themes emergent from the history of different localities in the whole globe – the glocal perspective – and explains the interest in Chinese scroll art as a model for large paintings that must be seen in transit across them.

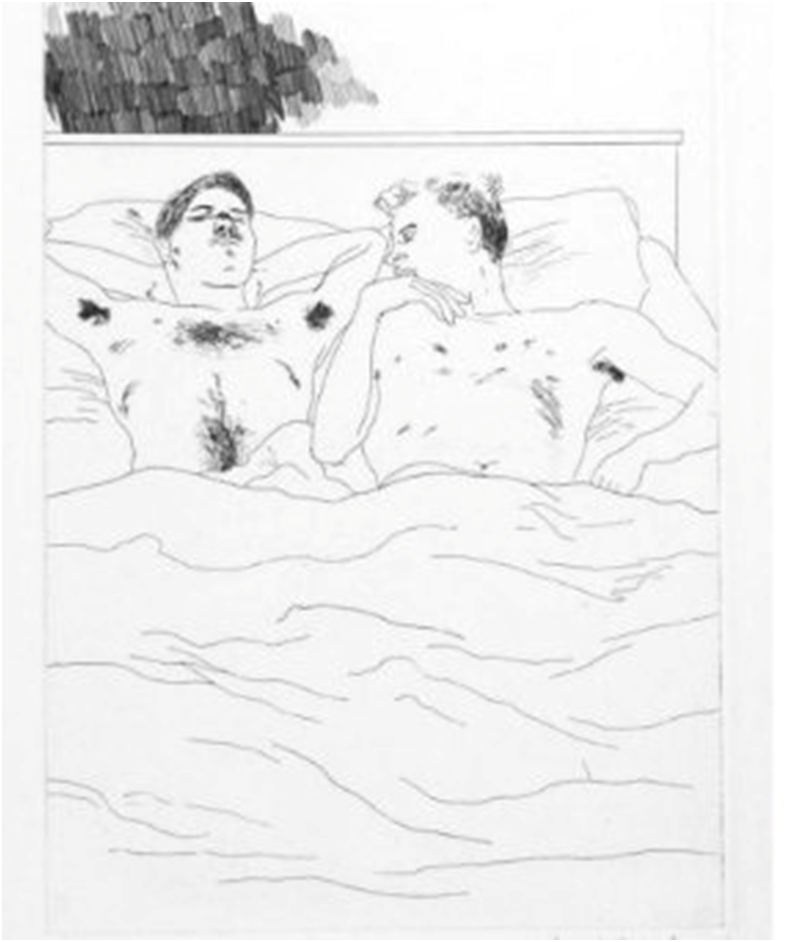

The themes here run variously through the first two substantial chapters of the book, with the first by Helen Little concentrating on the history of the Tate and its relationship to Hockney as indicative of themes 1, 3 and 4 particularly, but touching on the second in relation to the poetic work of Cavafy as an influence being used by Hockney ‘to draw attention to the British government’s controversial anti-gay Clause 28, which proposed to ban local authorities from promoting homosexuality’.[3] The beauty of the book however is that drier, if necessary, treatment of the relation of art to sexual and cultural politics is supported by one of the most beautiful short pieces. In the latter a major contemporary queer poet links his receipt from an early boyfriend of a copy of Cavafy’s poems to gift him at a Christmas home visit in Barnsley to Hockney’s past in Bradford and the latter’s etchings, which suddenly seem to be ‘devoid of wider context’ and to ‘luxuriate in their moment’.

Decontextualised readings of art that stress the timeless are not usually my preference but we have here to remember how such the public representation of these private moments have been historically denied to queer men in love. McMillan expresses this understatedly but beautifully in saying:

What matters is how someone turns in a bed, opens a page of a book, reads a poem to a lover who, despite not fully grasping what is being said, allows the words like dawn light through a blind, to wash over them. For a moment, just for a moment, their hands behind their heads as they listen, the sheets folded like paper at their waist, their head tilted, just for a moment, they become a work of art’.[4]

The feeling here of a timelessness that is nevertheless momentary and locked between balance of the stasis and flow of the reading of the syntax here may have been said before – by Browning in Two In The Campagna for instance which attempts to locate the infinite in the finite – but never to the benefit of two men in love with each other and claiming their rights outside time. In fact such a moment is crucially linked to the history which includes the fight against Section 28 of the Local Government Act and the homophobia which drove it. McMillan knows this.

The second substantial chapter by Gregory Salter specifically tackles queer history and specifically in the 1960s when Hockney emerged as an artist and began to devise a language for his art that is provocatively political by being adamant about the right to be personal. History here meets the biographical in Hockney’s acquisition of styles from different parts of the world that estranged audiences from Western expectations, such as Egypt (in part through contact with Cavafy’s Alexandria) before taking the fight to the USA and finding much in intra-national relations between cultures to ‘play a small, but not insignificant, part of his story of queer discovery’.[5] Stepping up to supplement this last point is the queer socialist writer, Owen Jones, in a piece which forever hints at the links between political action and the alternative of experiencing, and continually reliving triggered memories of, personal trauma. The hints are not beautifully written as in McMillan but that openly tell nevertheless of things which ‘can cause profound distress’ the statistics of higher levels of mental distress in queer people and the depiction of a ‘journey in which pain and turmoil is inherent’ in Hockney’s modern version of Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress.

This book is full of different perspectives on art and its relation to perceptions of self and world and the interactions between these things. If one essay were to strike as conveying the most profound grasp of Hockney’s theories of multiple perspective and multiple foci of attention it would, unsurprisingly, be that of Ali Smith who constantly walks you past and stands near or far from her subject, which is Hockney’s Bigger Trees Near Warter Or/Ou Peinture Sur Le Motif Pour le Nouvel Age Post-Photographique (2007) It is a title which bows to Cezanne in its French section while still continuing the campaign against both the camera and the camera – obscura. The last words of this piece are so Ali Smith but so Hockney too and remind us of Hockney’s gift to her of his seasonal tree pictures for her novels on the seasons.

It’s the possibility of something else in everything. Something further. Something more.[6]

I felt that, when I started this, I had a great deal to say about the experiences that stimulated me in other ways than to emotion and recognition within this book but I find now I have none. Perhaps it is enough to just say that in this book ‘the possibility of something else in everything’ remains open. Of course it is only open if you look and if you refuse to go beyond learning as a matter of the acquisition of transferable knowledge and skills. This book penetrates to the values that make art viable as a thing that must respond to individuals, groups and to something deeper – that makes fairness, honest and beauty worth living for.

Our lives interconnect in strange ways. As a young man I. stayed in the flat of a friend near Russell Square, a lecturer in University College London, with my husband (still my husband though I am now 67) and on the wall was a drawing that belonged to Nikos Stangos, who had not yet died of AIDS that this lecturer had in care for Stephen Spender – a mutual friend of both. That drawing was the one described by Andrew McMillan. I will always remember the lines of that drawing but I have only felt able to interpret since reading McMillan’s short prose piece.

All the best

Steve

[1] Quotations from Allen Ellenzweig (2021: 413) George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye New York, Oxford University Press.

[2] Quotations in paragraph and citation of Saslow in Ibid: 413f.

[3] Helen Little (2021: 16) ‘The Road To the Studio: David Hockney and the Tate’ in Helen Little (ed.) op.cit. 13 – 25.

[4] Andrew McMillan (2021: 97) ‘Thoughts From The Dull Village’ in Helen Little (ed.) op.cit: 96f.

[5] Gregory Salter (2021: 34) ’David Hockney and Queer History in the 1960s’ in Helen Little (ed.) op.cit: 27 – 35

[6] Ali Smith (2021: 197) ‘A Bigger Trees’ in Helen Little (ed.) op.cit: 196f.

3 thoughts on “Hockney’s life-long challenge to the facilitation by the Art Establishment of the ‘puritanical, abstract and conceptual’ is just one of the ways that he has wished to move the focus of the stories we tell to characterise modern art. This blog reflects Helen Little’s (ed.) wonderful 2021 book ‘David Hockney: Moving Focus: Works from the Tate Collection’ London, Tate Publishing.”