What more can art history and the institutions representing the traditions of art in the UK do? This is a blog based on a visit made on the 4th March 2022 to York Art Gallery (York 2022 blog No. 1).

There is a myth that the world of art and artists has always had porous boundaries that have allowed for the expression of difference. This myth is sometimes invoked to critique any move by art institutions to see its duty in relation to differences in its audiences as tokenistic and pandering to standards below those which have ensured high quality in the art. One such ‘standard’ is a belief in the enduring value of Old Masters, we are offered to gaze upon in our Galleries at national or local level. This has never been a satisfactory argument, particularly since courting an audience for its interest in queered sexualities was always part of the way in which even ‘Old Masters – and some Old Mistresses (such as Artemisia Gentileschi) in Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock’s ironic term – scoured classical mythology. Such audiences delighted as much in the secret nature of this queer exploration, which could even be passed off as having a highly moral allegoric intention.

But the association of queerness with secrecy and the arcane enabled those challenges to the norms of society to remain blunted in anything but the lives of a few. As in so many other respects, the Bloomsbury Group, as a collection of largely wealthy and established (even establishment) figures, stands at a cusp of a social transition wherein a largely secreted lifestyle and bold but arcane artistic practice began to push tentative feelers into public consciousness. Their practice as artists can be seen to redress the secrecy that saw any attempt to unpick the complicated sexualities of its members as a slur on ‘great art’. The feelers they allowed to ‘come out’ from their inner lives as individuals and psychosexual networks (even chosen families) could easily be withdrawn or denied if they were at risk of too much publicity. But ‘feelers’ there were, even in, for the example the classic novels of both Virginia Woolf and E.M. Forster, both of whom in their different ways embraced the queering of what we understand by the values by which we might live, love and communicate.

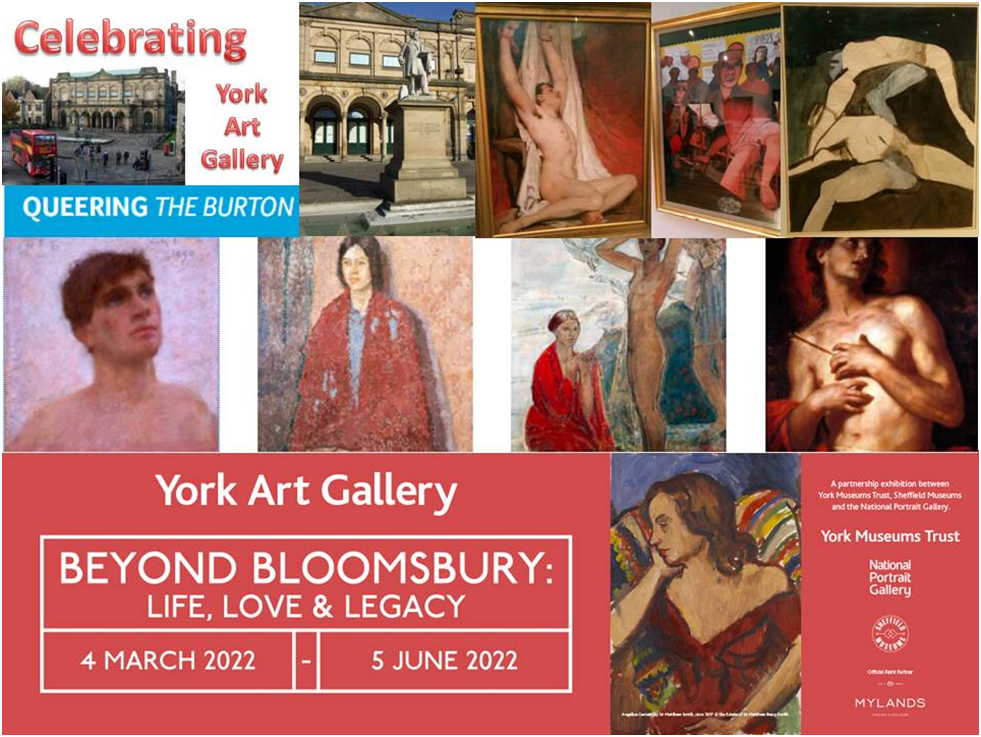

Hence, it is a tremendous boon that the National Portrait Gallery’s collection of Bloomsbury portraits and other material has found it was to go to York at a time when lots of strands and connections can be made between it, with additions from the York and other regional archives, and the Gallery’s professed duty to the open LGBTQIA+ community. Some of my consideration of this will go into a second blog on this York visit about this tremendous exhibition.

However, before looking at how the York Gallery has addressed the queer community more generally, it is worth noting that the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) Collection in London (The London Gallery is currently being refurbished – hence the movement of some of these prize artefacts) has allowed, and collaborated in, its Bloomsbury related collection to be supplemented from regional galleries and interpretively queered. Behind the project are co-curators from York and Sheffield Galleries, but the strategy involved too specifiable links with the queer community in York through the LGBT Forum in the city and artists who felt allied to the cause. They also linked the joy to be had in looking at classic art to contemporary artists who wished to reflect learning from that art in their own new works and in sharing their enthusiasm for it in practical teaching involving the making of art by community members who do not consider themselves artists.

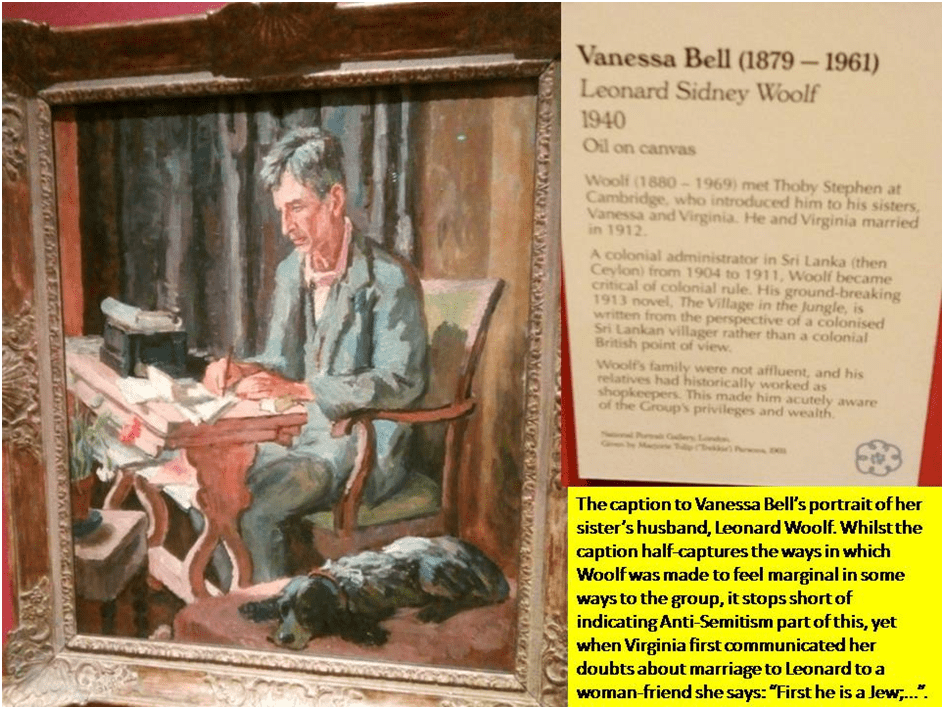

The artists involved treat work from Bloomsbury critically and not just reverently by holding against it important perspectives missed by the Group itself, which shared the widespread oppressive attitudes of the period. Not all those points are as stressed as they might be. For instance, Leonard Woolf was from a background far less privileged than the rest of the Group, including his wife, Virginia Woolf. This led to a kind marginalisation of him and this is a point not lost in the caption commentary of Vanessa Bell’s portrait of him. However Leonard was also Jewish. Whilst the caption captures one way in which Woolf was made to feel marginal in to the group, it stops short of indicating the Anti-Semitism he experienced in the manner and tone of the others. For instance, when Virginia first communicated her doubts about marriage to Leonard Woolf to a woman-friend she says: “First he is a Jew; …”.[1]

Perhaps as a reflection of community involvement in part, but certainly reflexive of the art of one of the involved artists in the curation, Sahara Longe, is the respectful treatment of the complex typing of black queer men by queer white men. Consider, for instance, this paragraph from the NPG’s webpage on this project.

In a section on Duncan Grant and his circle, a new portrait of Patrick Nelson (1916 – 1963) by Sahara Longe (born 1994) is paired with a nude depiction of the same sitter by Duncan Grant. Both of these works offer an insight into Grant and Nelson’s loving relationship, whilst highlighting the prevalence of exoticism. This form of racist stereotyping involves the fetishisation of black subjects by white artists. Grant’s nude poses questions about the nature of his attraction and how this is expressed in the way in which he painted Nelson. Longe’s sensitive portrayal of Nelson gives him agency beyond this relationship.[2]

Community connections work in the co-selection, if not exactly co-curation, of art (it is suggested by the York Gallery’s own website) by seeing paintings not as just fine pieces of art but as ‘telling the stories and sharing the perspectives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) people’. And this is not just a metaphor. The importance of ‘coming out’ stories in our communities can be mirrored in the way that the material related to queer lives is silenced in stories of the making and sharing of many artworks of different kinds. Hence the same webpage cited above goes on to say that: ‘Art works from York Art Galleries collections will be ‘coming out’ from the stores as well as looking again at some of the art already on display from an LGBTQIA perspective’. [3]

But visiting York Gallery on the 4th March was for me a tremendously joyous experience. Having attended because I love all things related to Bloomsbury and Duncan Grant in particular, I found this tremendous space (already deeply valued by me for its openness as an art institution) yet more welcoming. Here I could see paintings I had longed to see in the past, such as Edward Burra’s The Silver Dollar Bar and Keith Vaughan pieces (one in the Burton and one in the exhibition but they were cross-referenced in the captions) that open up gaps in the history of intersectional oppressions. In the webpage dedicated to the project, Reyahn King, Chief Executive Officer at York Museums Trust, says:

“It is essential that York Art Gallery is an inclusive and welcoming space for all communities, and I want to thank York LGBT Forum, our Allies Group and the wider local LGBTQIA+ Community for their commitment to this important work”.[4]

For I, as an example that might be true for others, felt welcomed at the Gallery with respect and regard to any and every aspect of my being and personality that could be called forth by any part of it or its ‘spirit’; not least that that longed to break my own deep-rooted mistrust of groups and institutions. I think that many both working class and queer persons other than myself (since at root I am an accidentally ‘over-educated’ working-class boy inside still though 67, and masked by an acquired linguistic facility that sometimes feels insecure). To see the Gallery (as a whole and not just the Exhibition) was for me being encouraged, without being simultaneously patronised, to be part of something. For this reason, I wanted to emphasise this. I could start with the community involvement in the Bloomsbury exhibition itself, wherein all comers are invited to participate in producing work modelled on but not copied on Bloomsbury stimuli or that of the ‘Rebel Art Group’ which was to feed into pre-Second-World-war English and Scottish Futurism and, its offshoot, Vorticism. The following collage shows some of the work made by collaboratively under the direction of Lydia Caprani:

These pieces are not merely derivative but are clearly based on Roger Fry’s Omega Workshop designs and continuing work by Grant at his home at Charleston, shared with Vanessa Bell and a number of other male lovers in sequence, as well as work which feels to me to be based on the best Vorticist work of David Bomberg, such as The Mud Path of 1914.

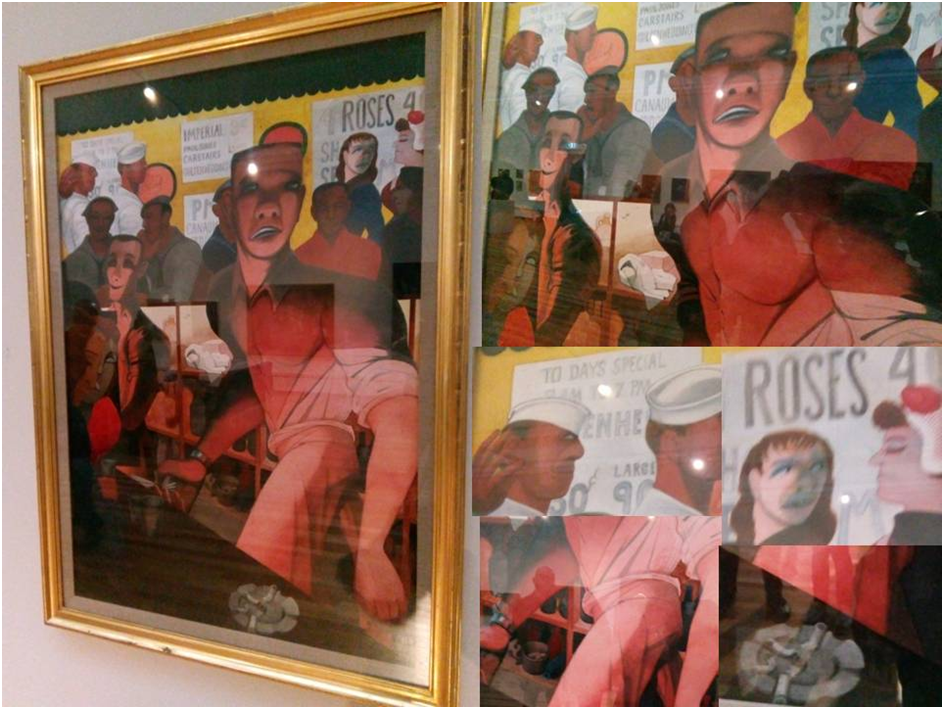

But for me, the main delight was the queering of the Burton display gallery itself, which is approached via a dark Edwardian style staircase lined with the more conventional William Etty portraits. The first delight was the presence of artworks I knew to be present in the York archive but which were rarely shown, such The Silver Dollar Bar, painted in about 1953, showing a bar in Harlem where queer and black culture thrived and of which Burra knew, mixed as it was with his perennial fascination with the life of international sailors and the easy sex with which they were rightly or wrongly associated. I have wanted to see this painting whilst working on Edward Burra in an unfinished MA in Art History, one piece of which had also concentrated on a Harlem night-life interior scene.

For this picture is as near as we will get to seeing how highlights of our global history such as the Harlem Renaissance ensured that queer life was formed in an awareness of the intersection of different expressions of both being and sexuality, that was sometimes reflected in the status of domains where this life was lived like the Harlem bars. It emphasises too the importance of ‘non-sexual’ motifs such as the awareness of the ubiquity and complex function of the gaze – in assessing others for their availability, danger or chosen identity in this liminal space. Eyes admire, test, as well as assess others and express solidarities amidst difference, as in the representation of the transgender persons at the viewer’s right of the picture as they come into the confronting gaze of newly entered sailors on the viewer’s left. The focus on eyes is in this painting, as in others by Burra, also registered in the disturbing shifts of variable perspective, such as that that picks up the detail of the ashtray at the bottom of the picture frame level whilst scan the notices on the distant bar wall, which we see only because it is reflected in the mirror behind the bartender’s beautiful flat head. The use of mirrors and estranging light is typical of Burra but it reflects a lifestyle too full of stories now difficult to recall because venues in which queer people meet are no longer framed by the same anticipations of both excitement and concomitant danger.

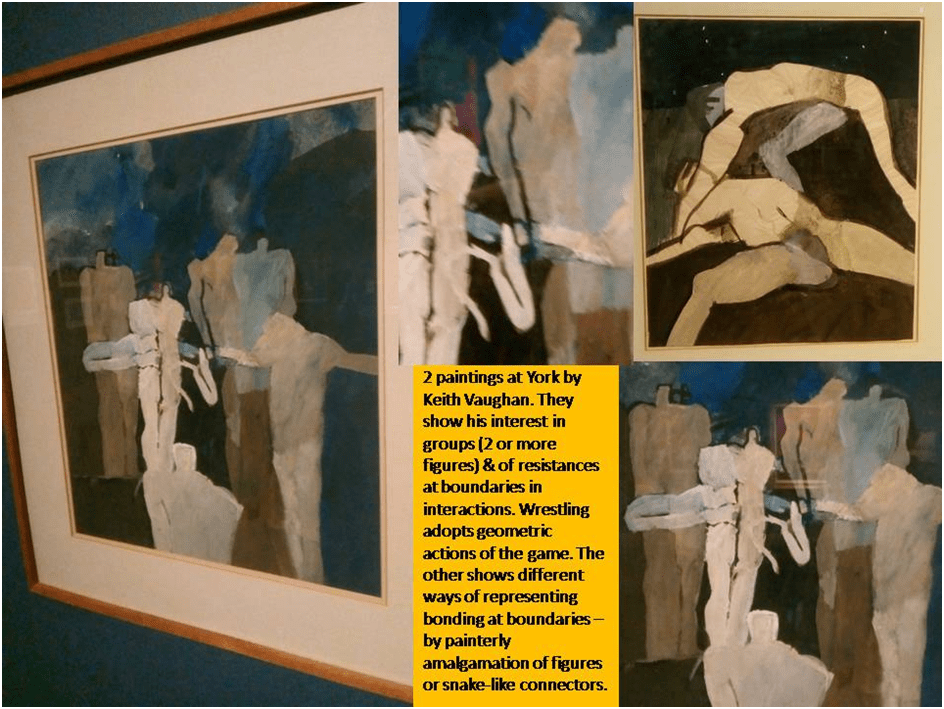

Likewise I saw in the Queered Burton Gallery At York paintings by Keith Vaughan I did not know though I had formed an interest (as shown in this blog) and on whom I had determined to base my abandoned (there are reasons why I distrust institutions however ‘open’ they claim to be) MA dissertation (my draft plan in the blog at this link). These paintings fuelled my intellectual interests again about how queer personal interactions and groupings became a focus in post-war Britain , Vaughan’s paintings showing deep attention to how and why the idea of ‘assembly’ was charged for queer people by the marginalisation of their groupings. Such groups often show connectivity that he represents by the avoidance of lines and the liminal effect of coloured patches of paint that blur into each other. At other times, following his Laocoön series of paintings, he shows connectors between bodies which look like snake-like creatures. Hard lines bounding a figure may show where groups of marginalised people disintegrate, under oppressive surveillance or interference, into individuals in isolation. Here is a collage of the two paintings (I neglected to take the names and details):

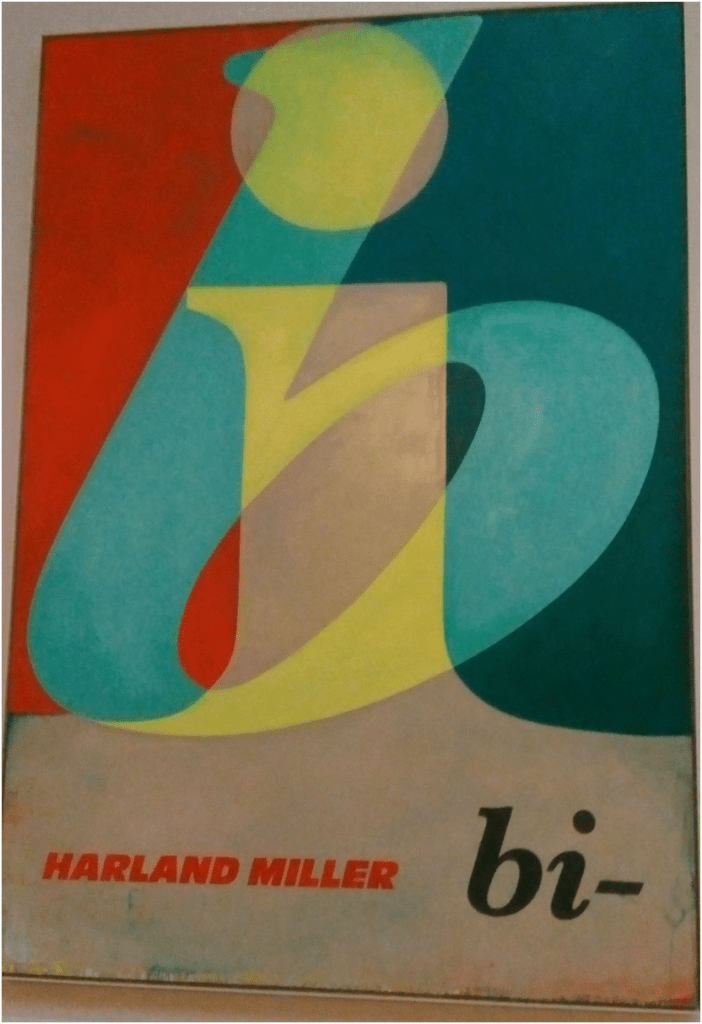

Vaughan’s paintings speak to members of the LGBTQ+ community in ways I don’t see in other painters even where the figuration is more realistic or intended to show figures that have become objects of desire as in John Minton’s paintings. These then speak to me about and at the level of my thoughts and feelings about queer communities. Other paintings cover the diversities of our communities – over sex/gender boundaries too. Indeed Vaughan claimed to be doing that but he doesn’t always convince that his figures are not intended to represent interactions only between men. I hesitate to examine the lesbian art figures because of fear of colonisation of them, though I do not feel that about Harland Miller’s Bi, which both posits the idea of a binary biological sexual division implied in the term ‘bisexual’ but in fact makes us celebrate a much wider than binary diversity in the meaning of that word in his painting because of the play of multiple colours within it that also trouble the calligraphy of the word into a more celebratory multiplicity.

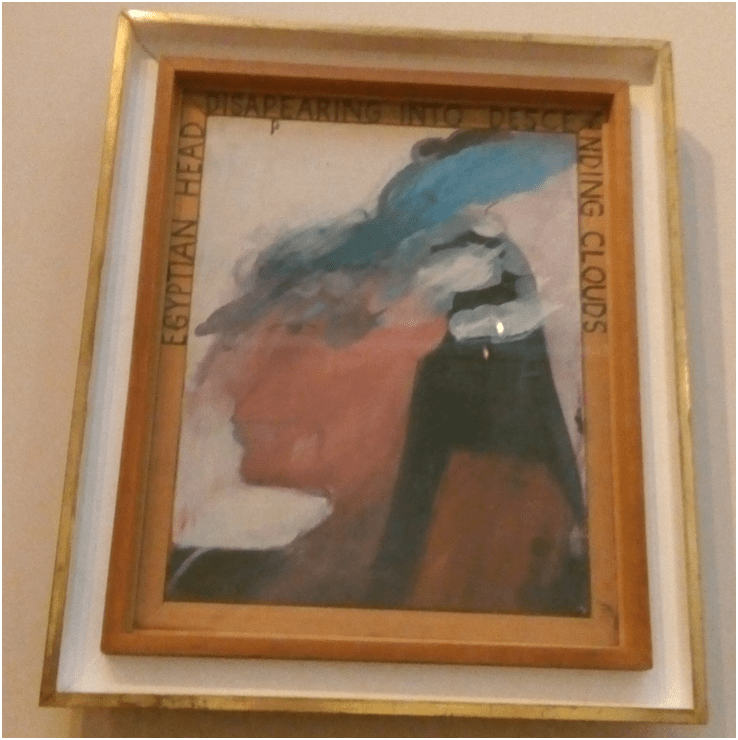

That there is an early Hockney is tremendous and needs a showing. Indeed its use of painterly blurring of lines (to be expected in a painting called Egyptian Head Disappearing Into Descending Clouds, written across the inner frame of the picture in fragmented sentence using a kind of calligraphic printed writing) reminds me somewhat of Vaughan’ mergence of figure and background for thematic purpose. It suggests something about the coded nature of queer desire in the period of its painting:

However, the York community has long expressed its fascination with the queerness in every which way, that cannot have been totally consciously intended, in Sir William Etty’s most famous male nude. He collected guardsmen from the barracks it is believed to take to his studio to paint in classical poses. These were intended in part as ‘life studies’ usually done by younger painters, but which he continued to make throughout his life. It is for this reason that Etty justified the tying up of this nude. There is a fascinated desire in the demonstration of potential pain, despair and powerful subjection to the gaze of his nude young men that is just missing from his fleshy female nudes – something I noticed when I first saw this painting in the Flesh exhibition on York Gallery’s re-opening in 2017 (but did not include in my brief blog – see this link).

However, the purpose of this first blog: a mere preface to the one intended on the Bloomsbury legacy exhibition which was my intended subject, is genuinely only to thank York Art Gallery and to show this through some favourite paintings.

Job done I think. The next blog will hopefully be more serious in extending my own thinking on Bloomsbury as an artistic and literary queer movement. Let’s hope so. LOL.

All the best

Steve

[1] A letter to Madge Vaughan probably dated in 1911-12 by Virginia Woolf cited in Francis Spalding (2021, 4th ed.: 39) The Bloomsbury Group, London, National Portrait Gallery Publications.

[2] Cited from NPG Gallery website: https://www.npg.org.uk/blog/queer-connections-the-bloomsbury-group

[3] Cited from text of webpage of York Museums Trust on ‘Queering the Burton’: Queering the Burton Gallery | York Art Gallery

[4] Ibid.

5 thoughts on “What more can art history and the institutions representing the traditions of art in the UK do? This is a ‘thank you’ blog based on a visit made on the 4th March 2022 to York Art Gallery (York 2022 blog No. 1).”