‘“…, the way of seeing outside the limits of architecture is the one that reveals the real truth and … is what illuminates more”/ … “The art that presents us with more difficulties is the most agreeable and therefore the most intellectual”’.[1] Faking it – An idea applied to the availability and originality of great art OR to the project of realising the Embodied Spiritual in Paint. This blog is on El Greco’s Christ on the Cross (c. 1610), The Hispanic Society of America, New York, NY version [on loan] of The Holy Family (ca. 1585), The Baptism of Christ (a digitally processed facsimile) and A Tabernacle of The Risen Christ (a 2019 digitally processed facsimile): The showcasing of original and facsimile Works by El Greco [Domenikó Theotokópoulos] (1541 – 1614). Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland: Reflections and Discussions in my free time on some of the Paintings, as part of a personal learning project related to the Golden Age of Spanish Painting (No.2).

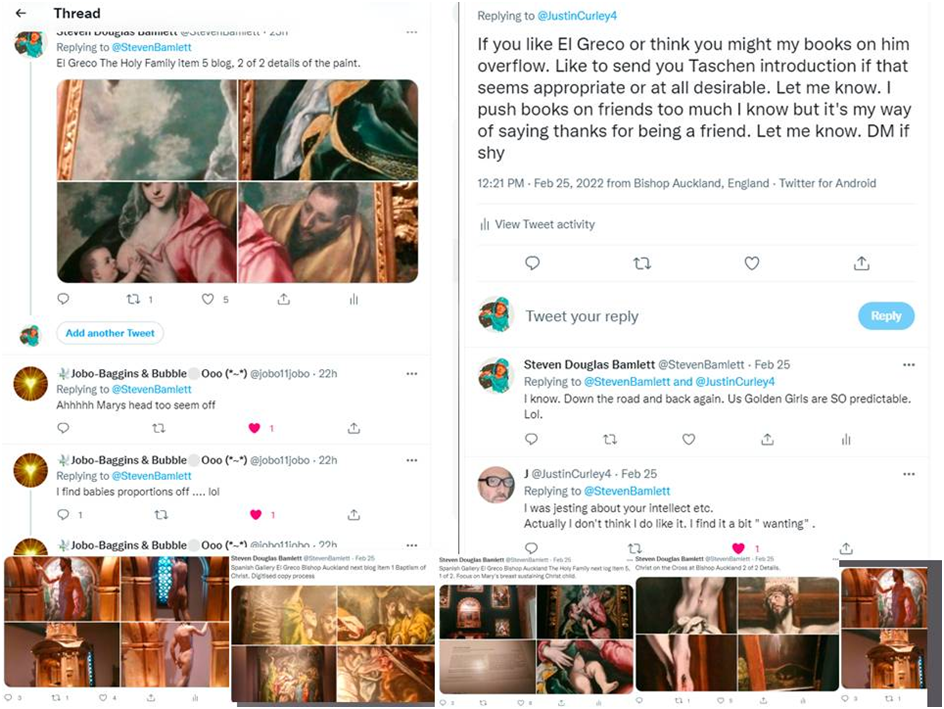

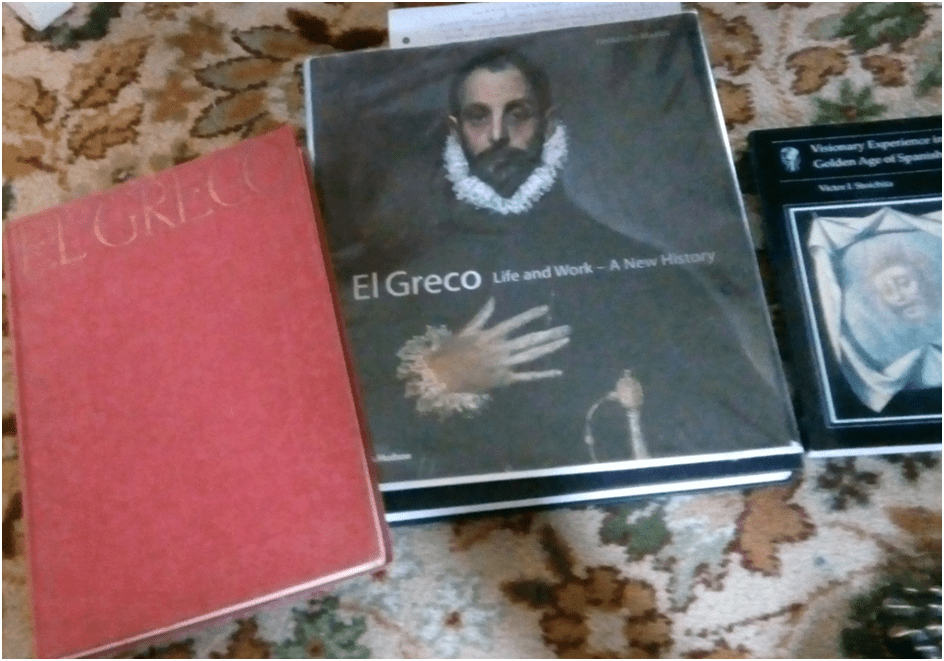

In this instance I think I need to start this blog by reflecting on why I blog at all. The reason was from the beginning to ensure that conversations and reflections I had continued in my own head so that they might ensure some degree of learning. This learning could be about reflection on either the content of a topic or the transmission to others of the knowledge, methods and values this reflection occasioned, which to me constitutes the learning process. I include the aim of transmitting the messages produced by the process but realistically I have no expectations of an audience, or hope of feedback on my blogs; although both are welcome if they are intended to share the process of learning for all participants. This blog comes from a series that are intended also to make me more familiar with the acquired and temporarily borrowed holdings in the collection of the Spanish Art Gallery in Bishop Auckland, local to me. I tend to post on social media (Twitter mainly) that I am about to blog and to post my own amateur photographs of resources I am writing about or using in the concomitant learning required. Sometimes I get feedback at this stage.

This was the case in this instance and I want to use feedback from friends, who have made the learning experience more productive and engaging, at a deeper level than might have been the case. I believe that often positive statements about the work of artists already in the established canon reflect very little but the social value that this placement reflects onto them; that there is an acceptance of the works’ value in these cases without any consideration whether the person actually likes or receives any stimulus to engage with the art work. I have no doubt that many people who claim to ‘love’ Shakespeare may never have engaged at all with the text or production of his plays. This will be true equally of visual art by Michelangelo, Rembrandt or Van Gogh. Hence the most useful responses I often find to work or even thought about the work is one that is integral to the process of looking at something as if for the first time and seeing it as a stimulus that cannot be understood or liked without some initial feelings of dislike (even repulsion) or questioning of its value in human terms.

El Greco remains less popularly venerated than examples I have used. He was however loved in the twentieth century because he appeared, at least superficially, to predate the experiments with seeing of the Impressionists, Cubists (not least Picasso for numerous reasons), Neo-Romantics and Surrealists. Yet the approach that sees his work as a precursor for the ‘modern’ does not feel to me productive on its own anymore than just simply seeing it as an attempt to marry Oriental-Byzantine models (of figuration and colour) to those of the West. We need to know what we are looking at when we look at his art, first.

I was delighted then that very dear friends came forward with the barriers that stood in the way of valuing the photographs of the paintings posted.

The delight arises because discussion in everyday language about the value of art is so often denied to us by institutions that pretend to preserve the values of individual and community learning. In each case here my friends find something wanting in the EL Greco examples offered in tweets and did not, without some provision for later escape, commit to interest in my project. I admire that in them because, in doing so, they challenge those who feel they should be the ones setting the canon of what should be of interest, or beautiful or intellectually. And I hope it ever will be thus, seeing how much I have disliked, in my experience (as a teacher, learner or a mixture of both in institutions of further and higher education) of authority being used to propose that a right to a view on artistic production was based on institutionalised qualification or status alone.

In this case one friend raised the issue of the disturbance to our expectations or sense of human rightness of the artist’s distorted vision, whilst the other more radically points to something ‘missing’ at the heart of the aesthetic, intellectual and emotional experience of both El Greco’s art and his religion. Yet, as I pondered doing a blog to which I was already committed, these perceptions seemed a good starting point and more integral than those I had already proposed to myself from unaided thinking, feeling and reading. Of course, this feedback did also send me back to the reading and exploration of the art of El Greco as represented in the Spanish Gallery I had planned.

In a sense these feedback points, arising from casual discussion, raise the issue of what constitutes an adequate human response to art. By ‘adequate’ I mean here a response that possesses integrity, honesty and a desire to find an autonomous point of entry to the evaluation of art. The issue of authenticity is at the heart of the Spanish Gallery’s ‘holdings’ (including temporary holdings) of this artist in fact and this is for a number of reasons. The Gallery collection is based on that of an individual collector, Jonathan Ruffer, and at its base has few original works that are commonly admitted to be canonical other than for specialists of seventeenth-century Spanish art and its forebears. In a previous blog, I have shown that established art critics will, and do, use this to belittle the collection. Here, for instance is the London based art critic of The Guardian, Jonathan Jones, cited in my previous blog:

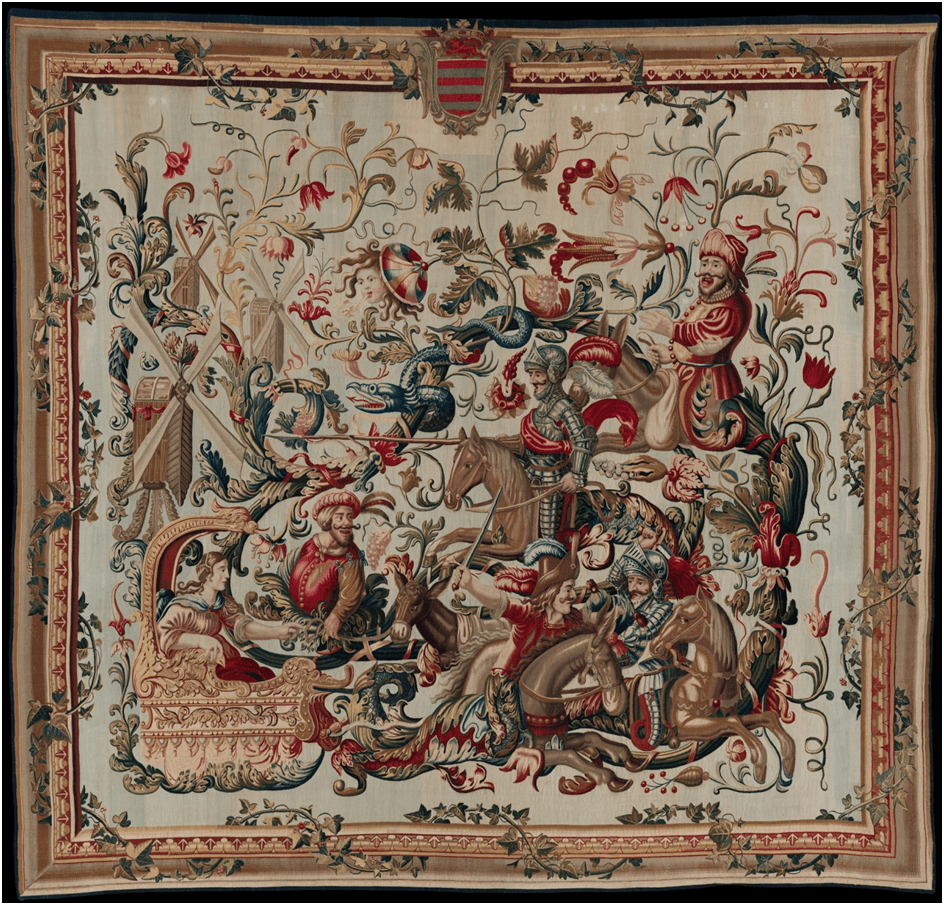

The “fakes” are more moving than the main collection. They take you to Spain. Bring on the chilled sherry and tapas. Actually, the Spanish Gallery will have a tapas bar soon. Meanwhile you’ll have to make do with some very rum displays of somewhat patchy art. It needs a Sancho Panza to keep this place a bit more real.[2]

Culturally ‘knowing’ elites oft wear their learning as if it were a policeman’s cosh, just as Jones used a Spanish Golden Age literary text, Cervantes’ Don Quixote, to spice his humour with verbal violence against a barbarian North and its upstart residents. These residents are stereotyped as those who think Spain is best represented not by an art gallery per se but a facsimile-based one that will provide them with a tapas bar in the fullness of time. The works he calls ‘fakes’ are actually digitally scanned and 3-D printed facsimiles of a highly expert level of quality. Moreover, they constitute a lower proportion to the total holdings than he can suggest here without sacrificing the humour to be got out of ignorant Northerners. Not only does Jones laud the ‘fakes’ in the Gallery most of all but suggests that fake responses to Spain, art and culture generally might have been expected of those who cannot tell ‘patchy art’ from truly great art. But though Sancho Panza in the great novel referenced does attempt to disabuse his master, Don Quixote of his exotic, or quixotic to give the literary model more of its authority, false or unusual ideas, he also facilitates some of the most potent defences of experience queered by authentic learning from ‘fake’ or imagined stimuli and prompts to a better world.[3]

“When life itself seems lunatic, who knows where madness lies? Perhaps to be too practical is madness. To surrender dreams — this may be madness. Too much sanity may be madness — and maddest of all: to see life as it is, and not as it should be!”

― Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Don Quixote

We live in a society that sees and produces knowledge and resources for learning as if they were merely and only a commodity open for sale and ‘ownership’ and to use as a functional tool in the pursuit of self-interest. Even used to display how we drop the names of art works in conversation, lieu of responding to them with some integrity and willingness to open oneself up to learning, they have that function.[4] But now retired from waged teaching and learning I can live in my own pretend paradise like the august Don (Don Quixote I mean rather than a university ‘don’). But, in truth, what is ‘patchy’ in Jonathan Jones’ view of my home town’s assets is his response. For to my town opening up stimuli to the dreams and madness that make for learning is a nobler aim than paying lip service to art aimed only at metropolitan elites. The ways the Gallery can open up a small market town to the stimulus of other cultures is discussed by Adam Lowe and Charlotte Skene Catling in the Spanish Gallery catalogue: in the section on its use of facsimile of Spanish art. Here is an intriguing and pregnant citation from that long complex discussion of how the themes of Golden Age Art resonate with the objectives of the use of facsimile models and modelling, especially on the 4th floor of the Gallery, of artworks as a process:

Rapture, transience, transformation and resurrection at the core of this exhibition. It is also designed to provoke questions. What is the function and purpose of art? What does it reveal? Where does its value lie? What is the relationship between an original and an authentic copy? … What can Spanish art contribute to a former mining town in the north-east of England? … .[5]

I find this perspective thrilling and, of course, it seemed entirely misunderstood by Jonathan Jones who thinks his function is to evaluate art without understanding what the term ‘art’ actually means beyond those associations he inherits from a divided culture: a culture of which he is on the privileged side. For in the perspective I have just quoted there are analogies with those raised by Justin and Joanne. A discussion of El Greco is a way forward into these issues because the Gallery possesses only one original work by that artist. It was bought in conjunction with the Art Fund, and it is a stupendous and once forgotten or lost version of the artist’s many variations and reinventions of the theme of Christ on the Cross. It is now much more common to speak of El Greco in terms of someone who continually reproduced the same theme with variation and invention, in order to extend the meanings, emotions and values that this theme might yield. This is, according to Guillaume Kientz, writing in 2020, is the source of what we call El Greco’s ‘sheer originality’ as a painter despite the fact that it had many influences in his own time, developing career and ‘variation of many compositional prototypes’. We don’t need to turn to the many attempts to explain the queerness of his images as ‘mad, eccentric, astigmatic, mystical’ or ‘heretical’. [6] Indeed sometimes the fight to establish this view seems never to end since I first came across it in the 1970s in an account first published in 1938 by Ludwig Goldscheider. He therein argued that it was not madness or astigmatism that fuelled El Greco’s singularities but the fact that ‘visualization and vision becomes a distinction in the treatment of form’.[7]. Later critics like Kientz have developed this idea, as in this example:

Drawing upon both his Byzantine and Italian training, he settled upon his own prototypes, imposed his own formulas, and repeated them, practising self-reference and self-quotation as he worked to generate a style so personal that it has become a signature readable across the centuries.[8]

And, as jubilant as that sounds, this originality cannot but alienate at some level some viewers, so that their discomfort with the lack of proportionality, compositional clarity (El Greco’s scenes as we shall see tend to clutter or crowd the available space in any of the spatial and temporal dimensions possible) is at first like Joanne’s. In all this experience there is inevitably a sense of something that is ‘missing’ (as Justin says it so well) from our expectation of a satisfying experience of art or religion. And I think we have to begin here when we campaign against the truly ‘fake’ in art, which is more often a thoughtless response entirely dependent on stereotypical institutional views of art than a genuine and living response.

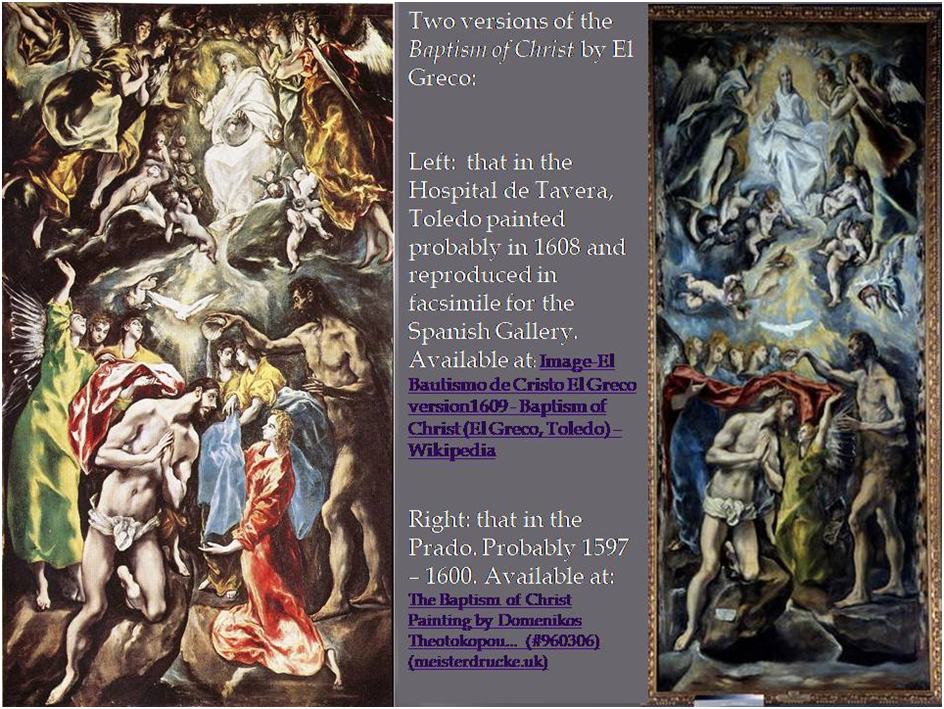

As we read more about El Greco we find that he himself often expressed his view (those quoted are most often those which annotate his copy of Vitruvius’ De Architectura) that he attempted to base his art on something ‘impossible’ rather than any notion of ‘reality’ (or even the ‘authority’ of the Church – in the Tridentine decree – to make events look ‘believable’ for instance).[9] This view might resonate too with David Davies’ constant description of El Greco’s objects (bodies, draperies and spaces) as ‘dematerialised’. For instance of draperies in the paintings, he says ‘their form and colour may be distinctive, but their texture cannot be discerned’. Note that our response is in part here necessarily based on something missing from our expectation of fine art, even when it is tied to the imitation of the invisible (perhaps even the ‘impossible’). The latter phenomena might include those which are ‘not based on the observation of natural phenomena, but conceived in the mind’, ‘the transcendental rather than the terrestrial’, or grounded in ‘spiritual being’.[10] Davies uses, amongst other paintings The Baptism of Christ (1608 – 28) to partly illustrate that point, as it does the disturbance of all proportionality and composition in many senses of both these words.

Davies very convincingly gives us a philosophical context for the interest in that which is ‘outside the limits’ of both convention and direct perception. That context is the extrapolation of Platonism into the work of Plotinus and other Neo-Platonists around how gross human sense gets access to the ideal’ which ‘cannot be perceived by the eye or the ear, or any of the senses’.[11] Such classical philosophies were already the common stock of the Byzantine Church Fathers and therefore of Byzantine Art too, in which he had been trained from early youth, but they do not explain how such a dependence on the philosophy of the ‘ideal’ can produce as cluttered a muddle (I do not use this term pejoratively) as the way space is filled in The Baptism of Christ. Indeed nothing can ‘other’ experience than, in my opinion which I owe to Justin, the possibility that El Greco’s art insistently (whether consciously or not) misses out anything that might ease access for his viewers to a rationale of what they are seeing, at least in religious painting.

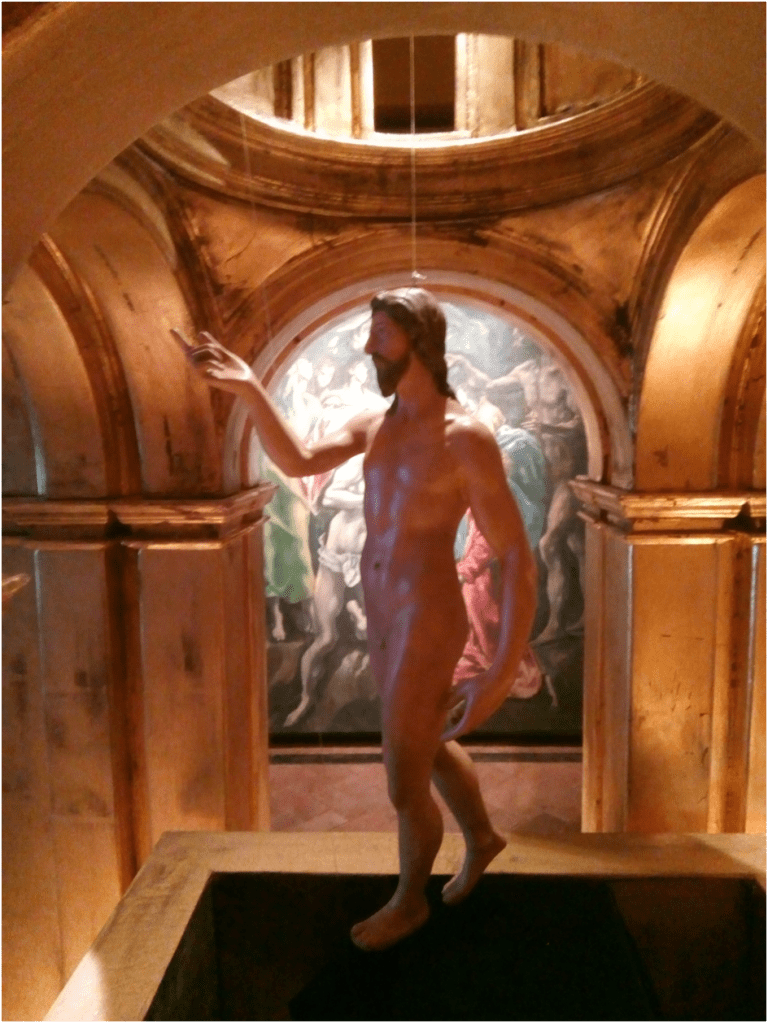

Now this is Indeed part of a visitor’s experience to the El Greco facsimiles on the 4th floor of the Spanish Gallery. One room juxtaposes facsimiles of parts of a sculpted Tabernacle paraded through the street to provide a visual polychrome model of Christ rising from the grave and ascending to Heaven, designed by El Greco, and his painting of The Baptism of Christ.

We can see here that the visitor to the Spanish Gallery has yet another difficulty presented to them, should they choose to acknowledge it, in dealing with the representation of time and space as they perform their visit. This is because these two artworks have an entirely different aesthetic, ecclesiastical and ritual context from each other both now and when they were seen in the seventeenth century. To put them together necessitates that the viewer is again, as Lowe and Catling Skene suggested, asking themselves questions about the ‘function and purpose of art’ and its pertinence to the spaces (even the ‘former mining town in the north-east of England’) in which this representation of art now sits. For me this is a means of making art relevant in ways that suit the purpose of a post-modern world, where norms can no longer provide unchallenged meanings. And this is possible because the entire answer to any viewer’s questions about their experience is missing from the objects they see unless they look reflexively to themselves, their motivation, and constitution as agents in the world.

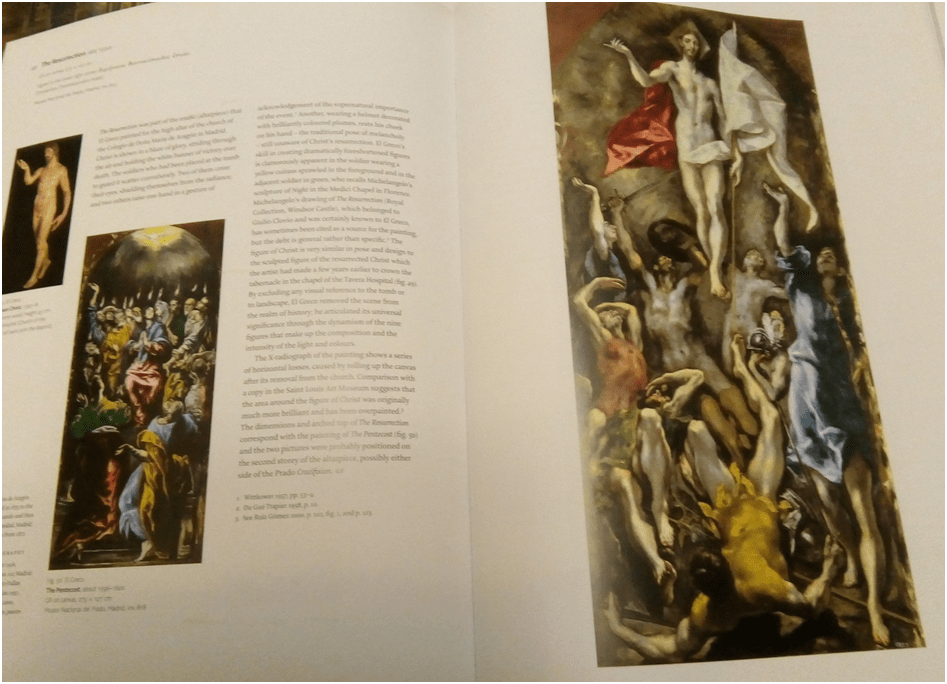

The Risen Christ may look somewhat like the figure in the painting called The Resurrection from late 1595 which the 2003 National Gallery Exhibition catalogue say where a picture of both is compared across one page opening and said to be ‘very similar in pose and design’.[12]

The painting The Resurrection itself is otherwise so crowded with figures and patterns of colour and form that it, as an artwork, bears no similarity at all with the ideation that justifies the role of the monochrome statuette as an aesthetic experience or as meaning. This painting appears to be a contrasting of patterns of aspirant ascension or the fall of flesh. This latter is represented in the Roman guards of Christ’s tomb, whom either seem to fall to a foreshortened prone position lateral to the viewer or are alternatively perceived to be falling even further into the illusory depth of the grave . The guards’ flesh is painted so much more solidly than Christ’s but here too anatomical proportions, where distorted, are distorted because of the complex and multiple points of view we take on their bodies, especially the guard clothed in yellow who seems to be sometimes being pushed out from the surface level of the picture horizontally towards the viewer and sometimes to a space vertically below the frame.

El Greco still gives due credit to something we might call normative human anatomy in the animated tabernacle of Risen Christ. As further evidence of that, the model itself is even thought to owe something to Michelangelo’s drawing of the same subject: that drawing owned by El Greco’s mentor in Italy, Giulio Clovio.[13] And this is clearly called for in a three dimensional polychrome statuette where at least four perspectives will or can be taken by a viewer as they walk around the tabernacle or the tabernacle passes through crowded streets in a religious subject where the audience is always moving. Here is then my collage of such perspectives.

But a facsimile lives in a different realm to an original in some respects, since it is as much a recreation of older processes of creation by newer ones (which they call photogrammetry) based largely on the collection of precise data than the informed but qualitatively evaluating judgement (where information also sometimes contains calculations) of a brain and the motion of a hand. The Factum Foundation indeed see the product of their facsimile work as much as about creating data to inform descriptions of the work of art, which they gift to academic institutions as about a visual effect on viewers. Their webpage on the Risen Christ is as much about the process of modern manufacture and is a good source of pictures of the mechanical dynamic of the piece, since those are not currently shown in the Spanish Gallery, and has a more professional photograph than mine of the facsimile in situ that I would encourage you to see.

The Baptism of Christ 2019 facsimile, based on that in the Hospital de Tavera, Toledo painted probably in 1608, is on a wall facing the tabernacle in its current situation in the Gallery. It is an interesting choice of painting to reproduce since it varies the representations of figures even more inventively. There are better photographs than mine below at the link in the last sentence. Here, for instance, the Christ figure is more heavily distorted than in earlier painting. Here is my collage of my photographs of it. Some will find for instance the curvature on the leg of Christ on the viewer’s left to have more plasticity than anatomical perception can validate. Moreover, the elongation of most bodies in the lower register of the painting (that representing earth rather than heaven) can be hard to justify even given the imaginative conceptualisation of a body aspiring to spiritual fluidity and ascension.

There are elements in the composition here too that yield to a rather unwanted drama (for some, though I love it), such as the waving hand of the angel in green which appears to be directed to a returning wave from angels in brown on the viewer’s right in the space dedicated to Heaven. The wave above, being done behind the back of the figure of God the Father seems rather shamefaced. It is a playful (indeed camp) element missing, for instance from the earlier version (probably 1597 – 1600) of The Baptism of Christ referred to by Leticia Ruiz Gomez (that in the Prado). She refers to the painting in order to show that the ‘adult angels and acrobatic cherubs’ are translations of ‘plaster, clay and wax modelli’ or figurines which El Greco used for different paintings by having them ‘dressed, hung, and lit in different arrangements’. Gomez’s point is that these are stylised methodologies for inventive variations in compositional style and ‘formal refinement’ but our copy of the Tavera (c. 1608) version has certainly more invention than the mere variable play with the arrangement of figurines implies, not least in that gorgeous communication between the angels that lighten the mood and animates compositional choices beyond mere pre-placements of modelli.

The methodologies of reproduction are again a focus with a whole new set of creative possibilities based on a different version of art and technology and referred to by Factum as the use of ‘the Lucida 3D Scanner (designed by artist and engineer Manuel Franquelo with support from Factum Foundation and Factum Arte) and panoramic photography’.[14] Again the meaning of art in this sentence speaks of differences in function and purpose implied by that word. And with that in mind we can return to the ‘original’ works in the Spanish Gallery.

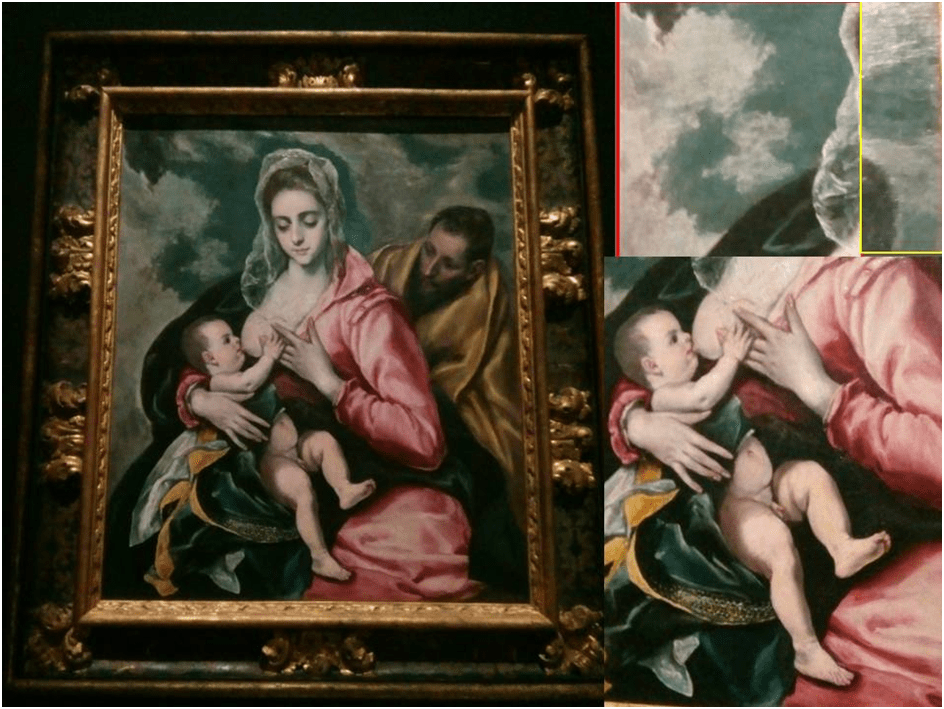

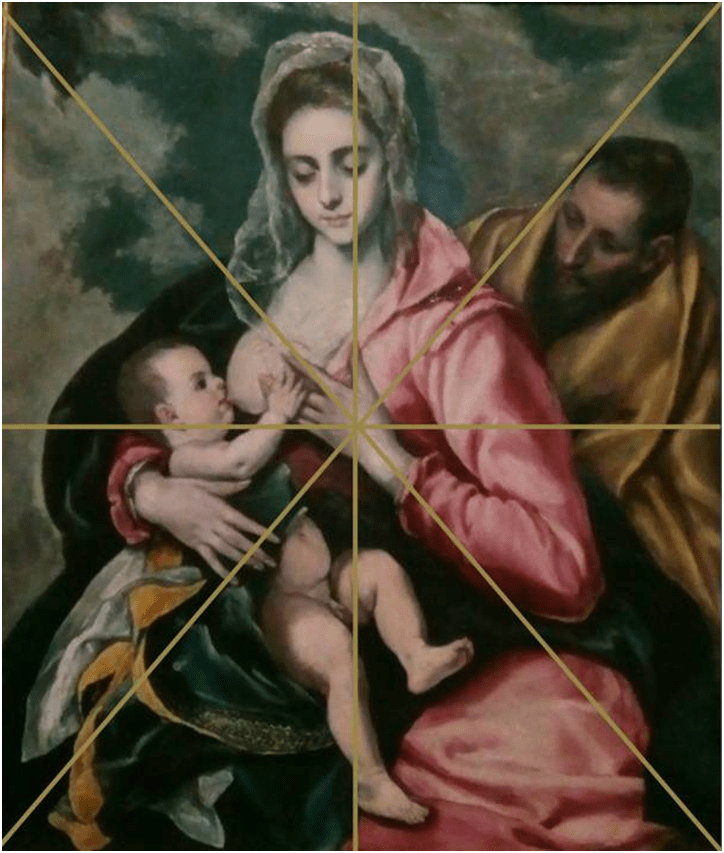

At the current moment the Spanish Gallery is showing the version of El Greco’s The Holy Family painted about 1585 (and therefore an earlier Spanish work of the master) owned by the Hispanic Society of America. The caption provided makes much of the spontaneity and freshness of the figures but also notes that the presentation of Joseph unusually as a young loving father figure also references ‘contemporary theological thinking’ in that he is ‘a vigorous mature protector of the Holy Family’. It was in the Counter-Reformation that Joseph became ‘newly prominent’.[15] The main Banking Hall, the building was once a bank) which now features the painting, on its East Wall, is itself an important placing of the painting on a wall of other images, including ones of Her as respectively, first as the birth-mother in a much more conventional Holy Family by Morales, but also as a grieving mother, in Juan de Valdés Leal’s The Descent From the Cross. She is also seen as a divine intermediary in Juan Martin Cabezalero’s Saint Idephonsus. Those last two can be seen (the first only in part on the left) in my photograph below, this photograph shows how the El Greco’s impact is increased because it is at ideal viewing height as one enters the hall.

But notions about the changing function and purpose of art is never far from us, and quite rightly so, in the Spanish Gallery. This is because, although these are original paintings, their setting is a reproduction of multiple other times and places since the experience reproduced in the hall is that of a church, if not a conventionally arranged one. On the East Wall of the Banking Hall (seen in the photograph) there is an appropriate low middle placing of a retablo, which once sat behind the altar, by Gómez the Elder, whilst on the facing West Wall, a wooden thirteenth-century Catalan crucified body of Christ looks back at the retablo. Yet the hall, with a viewing platform on the West wall from which to see the paintings high on the wall, also queers the sense of the sacred function of these images and helps us to see that even if original, they cannot be seen in a reproduced historical context but only an adapted one. We can keep this in mind as we turn back to the El Greco painting, of which I include my a collage of my personal photographs below.

Both Joanne and Justin found difficulty liking this. It is ‘earliest known treatment of the theme’, according to David Davies National Gallery catalogue, of the Holy Family by El Greco.[16] Apart from in the figure of Joseph who has a concerned but inferior placement in a less lighted place, the proportions of the relative anatomical and facial details of the figures of the both Madonna and Child seem difficult to reconcile with each other. There seems to be little thematic or even perspectival coherence in particular to the figure of Mary. My love of the painting resolves often into admiration for the colouring and lighting of the coloured clothing and wraps with their distinct patches of colour that are nevertheless variegated internally to show the play of light on a single colour and across the boundaries of differently coloured patches.

The painting resolves sometimes into a contrast of how paint is used in the top and bottom sections of the painting, with much wispy layering of paint to distinguish lightly the play of blue and white in the skies – merging against the evocation of the lace surrounding the Madonna’s head. Despite Davies saying, already cited above, of the draperies in El Greco that ‘their form and colour may be distinctive, but their texture cannot be discerned’, it is difficult to justify this statement in this case. Indeed it can only be true if one expects ‘texture’ in a represented world to conveyed by the texture of the paint itself. I can detect no impasto here, but visually I feel the textural difference of the cloths in imagining difference of feel between the ether of the painting’s sky and its solid, gold-enwoven linens, however flat the paint’s finish. And this backdrop of colour reinforces the structural placement, at the dead centre of the painting’s flat space, of the delicate interplay of hands between mother and child, which can be seen by bisecting the painted space. The found centre lies on the maternal hand, which itself points to the locked-together hands supporting her breast of both child and mother. There is a beautiful diagonally linear placement of these hands we can see that emphasises loving and very co-operative support of the child and child of mother. Davies is probably correct to say that the artifice of the way the sky is detailed with obvious light brush strokes visible to make the cloud’s evanescent feel visible in their artifice as a way of emphasising the absence of specific time and place – of space in general. This allows the family to seem both heavily seated and simultaneously to be floating in ether.[17]

Such beauty may not reduce the discomfort Joanne and Justin feel regarding the refusal of body parts to form a recognizable whole in a singular and stable perspective on them. Both mother and child can seem made up of badly integrated parts that demand to be seen as if from separate and moving perspectives. Is this a way of impelling some dynamism into the figures? It certainly has this effect for me as if the saccades of the eye will give movement to Christ’s lively legs. However Mary’s enormous breast – mirroring the motherly and full body suggested by her width of clothing seem to resolve into ideas – of ideal motherliness perhaps – that contradict the aristocratic and untouched feel of the young but fashionable face.

Davies may also be correct in saying that the painting fails to satisfy with its key foregrounded figures of Mary and Child by employing a way of seeing derived from his training in Italian Renaissance and Mannerist tropes – such as the ‘emphasis on the imagination and its extreme highly sophisticated ideal of grace and beauty’.[18] He explains the fragmented feel of the gaze on the female body as based the conventions of Petrarchan poetry in which specific parts of the female beloved’s body and face are selected separately for treatment without any holistic view of the woman – features such as a high (aristocratic) forehead, ‘doe-like eyes’ and so on. [19] Perhaps in this case we can see how the honest and integral response of Joanne and Justin is preferable to a mere acceptance of the supposed greatness of the Masters if we are to see art with any discrimination and set of values.

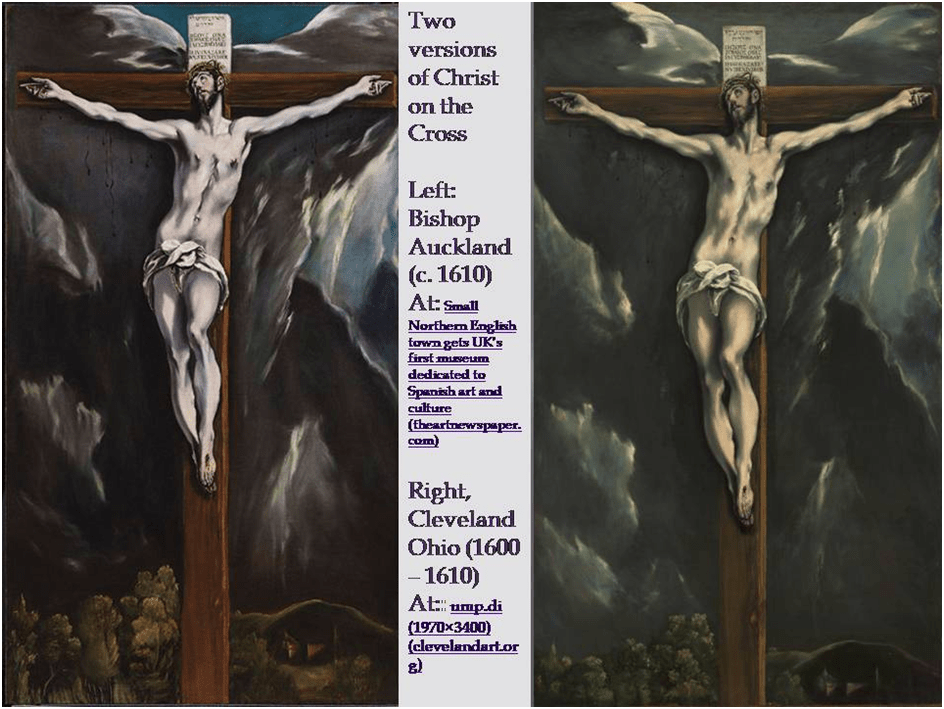

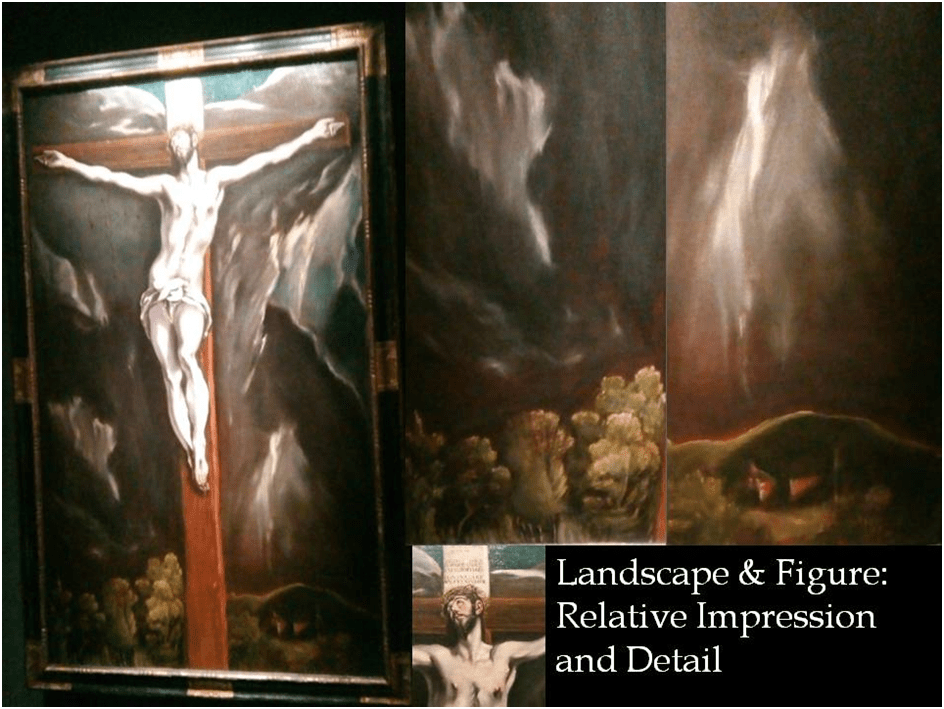

The issue of seeing clearly what is there matters even more when we approach an acknowledged mature treatment of Christ on the Cross by El Greco. This original version of the theme was purchased by the Spanish Gallery with the assistance of The Art Fund and had lain in the hands of an aristocratic house in Madrid since painted in about 1610 and now freshly restored to its, as far as we know, ‘original’ colours. These facts alone however make problematic the contemporary nature and purpose of art and its relation to notions of reproduction. The Spanish Gallery places it just beyond a door entrance such that a wall separates it from a much more conventional allegoric Crucifixion painting by Alonso Cano. It is possible for the viewer to see both together from a certain standpoint. The Gallery catalogue compares the painting to ‘the version in Cleveland Ohio’, and we might start with that comparison, poorly suggested (necessarily given my own low-level technological resources) in the collage below.

The catalogue comparison by Jonathan Ruffer reads:

In the [Cleveland, Ohio] painting, the landscape of Toledo is very precisely described and the body of Christ is impressionistic. Here, El Greco has reversed these priorities, with diffused landscape and carefully delineated body.[20]

From the reproductions I have now seen Ruffer’s text seems to create a more stark sense of difference in these respects than I find. However, the contrast at the level of landscape is noticeable in the comparative treatment of detail of the trees on the viewer’s left; which show leaf structure in the Ohio version but not in the Bishop Auckland one. But the details of landscape in both are relatively overshadowed by Christ and the like impressionistic turmoil of the skies that backgrounds both paintings – the ‘landscape’ merely forming a line at the base of the picture and requiring scrutiny at close quarters to distinguish well. Toledo can be seen cradled by a mountain at its rear in the Ohio version on the right but is very small. Comparatively a wider space is given to the alternative landscape space in Bishop Auckland but the hill that shelters the city of Toledo is much more visible than the vaguely illuminated outline of the city in this version. The city in this version fades into shafts of light apparently from above it. In comparison the city outline is clearer it seems in the Ohio version as might be seen in the collage below.

What this detail also shows is the impressionistic stormy sheet lightning effect of the skies which surround Christ. As in the early Holy Family painting, none of this effect is created, it seems to me, by impasto paint textures but as if by layering that is relatively invisible on the flat surface. Indeed layering effects in this painter are usually only discovered by X-rays or other depth scans. This flat effect is related structurally, since the central storm cloud is a cruciform aura in both paintings and minimise any differences in body and landscape. Of course it is impossible with access only from photographs to comment usefully on the impressionistic nature of the Ohio Christ’s body but the contrast is not very clear. It is therefore really important that the Factum Foundation is preparing, I believe, a facsimile of the Ohio version to show alongside or near the Bishop Auckland original. Here again art as a concept is foregrounded in ways that reveals the different social, intellectual and aesthetic functions of ways of looking at it by such methodologies.

This aside we can return to a ‘trialogue’ (to coin a term) between self, Justin and Joanne around what is missing or uncomfortable in this painting. This is as good a starting point for the originality of El Greco’s art. Its diversion from our expectations of both art and religion helps us get behind what does not appeal to us aesthetically or in any other way. Let’s look again at the painting and some (super)-human detail from it.

Photography too often fails us in the lighting offered by a gallery which appeals to direct observation more faithfully than through a modern self-regulating digital camera lens. Anatomically the figure is somewhat elongated and widened such that an ‘impossible’ arm span is complemented by an elongation of body. The vertical elongation naturalises what is surely an extremely artificial contrapposto pose of the body that exposes the torso and opens up the medial divide between the left and right muscle groups. In the muscular and spare, but not starved, figure that is Christ’s muscular body here makes that mid-muscular divide have the appearance of a dark scar or wound and emphasises the detail of nipples and navel, that in other contexts might be sexualised, as in fact they are still literally fetishised. This is not comfortable for normative gaze and if it were not for the supernatural interpretation suggested, the body is clearly offered up to the gaze, even by the exquisite placement of the delicate detailed feet realistically pinned and bleeding. Now that is not I think why anyone might see something missing from the representation – what is missing is I think any sense of authority for reading the image, which makes our sorrow and pity complicated by the excitement of physical and dynamic bodily appeal.

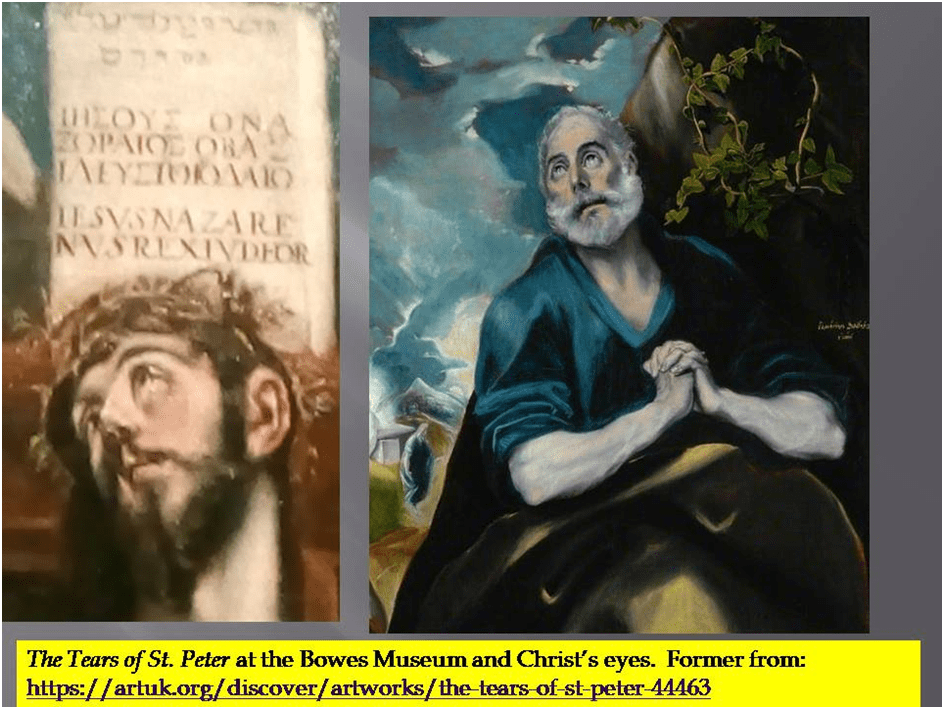

Likewise I find something difficult to read in the plangent statement that seems the easiest reading of the unnaturally enlarged upturned eyes of Christ, recalling those in The Tears of Saint Peter, a painting of 1580 – 1589 in the nearby Bowes museum at Barnard Castle. See them here:

The eyes, as it were, speak too much but what they say is self-evidently dependent on the moment of experience the viewer allows them to illustrate, whether of suffering, a fear of betrayal (or ‘forsaken’ whatever it complexly means) , guilt … one could go on. But this all seems too divorced from art seen as an object that is meant to satisfy and too near a demand upon its viewer to be touched with too great an immediacy, or at least I think so. Art history sometimes provides answers for these unsettling features of an absent authority in El Greco’s images. It used to be popular to seek some orthodoxy behind them in the Tridentine decrees but more recently Felipe Pereda has convincingly shown that that the evidence shows that El Greco was even problematic to contemporary orthodox Christians, even those who were his loyal friends (and certainly Philip III), and failed ‘to meet the expectations of his patrons or almost anybody else’.[21] David Davies once tried to shift the problem back into the lack of acquaintance of our own age and perhaps that of Catholic Imperial Spain of the Neo-Platonist tradition (and Plotinus in particular) well known to those trained in Byzantine art, but there is something considerably more troubling (‘missing’ as Justin says) than can be explained by education into arcane ancient philosophies.[22]

My own feeling and thinking response to El Greco’s art chimes best with unresolvable readings of the painter’s annotation on Vitruvius already mentioned and used in my title in part. For when El Greco talks about perception and the rather different, in his view, function and purpose of painting, in that it deals with ‘the impossible’ in a phrase I have already cited above (see text and footnote 9). For instance readers will always struggle with this note:

And if I could express with words what seeing is for a painter, it would seem a strange [thing], for seeing takes part in different features, but painting, being so universal, becomes speculative’.[23]

And indeed we ought to struggle, for the answer is here absent – locked in what El Greco cannot tell us without it seeming too queer for words. And if painting becomes speculative what does that mean – that it is incomplete without some concomitant work by the viewer to make something out of what is otherwise absent or fails to meet any expectation to which we are habituated and educated. The most helpful art historical suggestion I have come across comes from the exhaustive intellectual life by Fernando Marias in his consideration of how theory of art and its praxis emerged in the late 1580s for El Greco, when the study of Vitruvius was at its height. Marias is a subtle thinker but this summation of his thinking seems right even though it needs more elaboration, but not by me now. In the simplest terms Marias insists that El Greco purposively choose incompletion and apparent erroneous perception in his art to draw the viewer into it ever more closely. This is the sense of ‘difficulty’ and being beyond ‘the limits’ of an art I refer to in my title I think. I will leave you with part of the paragraph and encouragement that you read more. I will then move on:

…, the viewer had to be drawn closer to the fiction and be present in it, and therefore had to be integrated into the space of imitation, a space that was not determined a priori through the use of perspective, but a posteriori, from the reality and position of the viewer in relation to the work. …[24]

This has been a long haul of a blog and possibly leaves anyone with enough patience and good will to read it as lost as ever. Perhaps though that is precisely the virtue of the artist too – leave the reader / viewer in the speculative space that is the only true completion of great art. My next blog (no. 3 in this series) will be more relaxing I think though it looks at the larger holdings of the Spanish gallery of the painter Murillo. Hope I see someone there.

All the best

Steve

[1]Cited & translated from El Greco’s annotations To Vitruvius’ De Architectura by David Davies (2003:69) in ‘El Greco’s Religious Art: The Illumination and the Quickening of the Spirit’, an essay in David Davies (ed.) El Greco London, National Gallery Limited.

[2] Jonathan Jones (2021) ‘The Spanish Gallery review – would you like a scary fresco with your sherry and tapas?’ in The Guardian (online) (Fri 15 Oct 2021 10.08 BST) Available at: The Spanish Gallery review – would you like a scary fresco with your sherry and tapas? | Art | The Guardian

[3] Since I feel I am too old to re-consult the novel now, I’ll illustrate that merely by one of many possible (unreferenced) Goodreads ‘quotes’ (available at: Don Quixote Quotes by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (goodreads.com). I hope this illustrates that sometimes we can bend usefully to ‘fake’ sources, even when we know its ultimate inadequacy in the final analysis. For life is too short for any other attitude.

[4]As an example of my own ongoing reflection on this obsession of my own see this copy of a blog taken from my learning files on a MA course on Open and Distant Learning: The Ownership of Learning: issues related to conceptualising ‘learning’ as a product – Steve_Bamlett_blog (home.blog)

[5] Adam Lowe and Charlotte Skene Catling (2021: 93) ‘In Ictu Oculi: In the Blink of an Eye: Transience and Eternity in the Spanish Golden Age’ in Jonathan Ruffer (2021) The Spanish Gallery: A Guide to the Works of Art Bishop Auckland, The Auckland Project, pages 88 – 121.

[6] Guillaume Kientz (2020: 73) ‘ El Greco and the image: Between Invention and Variation’ in Rebecca J. Long (ed.) (2020) El Greco New Haven & London, Yale University Press for The Art Institute of Chicago, 72 – 81.

[7] Ludwig Goldscheider (1949 (first ed. 1938: 15) El Greco New York, Phaidon Publishers Inc.

[8] Kientz op.cit: 81

[9] “Painting deals with the impossible” a Vitruvius annotation cited relevantly in terms of my point by José Riello (2020: 34) ‘El Greco and Giulio Clovio: Three Gazes’ & Felipe Pereda (2020: 60) ‘El Greco, Religious Painter: Success and Failure’ both in ibid: 29 – 37, 51-60 respectively.

[10] David Davies op.cit: 45, 51, 52 & 55 respectively.

[11] Ibid: 70

[12] Catalogue entry for that painting in David Davies [Ed.] (2003) op cit pp. 174-175

[13] Ibid: 175

[14] Quoted from: Factum Foundation :: El Greco’s The Baptism of Christ

[15] Rebecca Long (ed.) op.cit: 133.

[16] Davies (ed.) op.cit: 142

[17] Ibid: 142f.

[18] Ibid: 143

[19] Ibid: 142

[20] Jonathan Ruffer (2021: 49) The Spanish Gallery: A Guide to the Works of Art Bishop Auckland, The Auckland Project

[21] Pereda op.cit: 51

[22] See Davies op. cit: 68-70.

[23] Cited Pereda op.cit: 58.

[24] Fernando Marías [trans. Paul Edson & Sander Berg] (2013: 181) El Greco: Life and Work – A New History London, Thames & Hudson Ltd

7 thoughts on “ ‘“The art that presents us with more difficulties is the most agreeable and therefore the most intellectual”’. This blog is about the El Greco paintings, ‘Christ on the Cross’ (c. 1610), ‘The Holy Family’ (ca. 1585), ‘The Baptism of Christ’ (a digitally processed facsimile) & ‘A Tabernacle of The Risen Christ’ (a digitally processed facsimile): The showcasing of original and facsimile Works by El Greco [Domenikó Theotokópoulos] (1541 – 1614) in the Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland: (No.2).”