‘Ne quis praeter Apellem Pingeret / For his ingeniosidades are not inferior to those that antiquity celebrates from the palette of that artist’.[1] A Young Boy Holding A Lance and Christ and the Woman of Samaria: Two paintings by Juan van der Hamen y León (1596 – 1631): Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland: Reflections and Discussions in my free time on some of the Paintings, as part of a personal learning project related to the Golden Age of Spanish Painting. (No.1).

The title of this blog starts by citing the Castilian court historian ,Tomás Tamayo de Vargas, praising the work of another historian, Lorenzo van der Hamen. That a man like Tomás Tamayo de Vargas, who praises another aspirant to such a role, such as van der Hamen, for the quality of his ‘picture in words’ of Philip II is a phenomenon that can be best understood in terms of the fact that it was necessary for all involved in seeking preferment to flatter the power of the Hapsburg monarchy of Spain. Indeed, William Jordan says, all privilege in the Madrid Court was ultimately bestowed by the crown’.[2] But this fulsome praise was also based in the authority of Latin classics, for Tomás quotes the classical Roman writer Horace to characterise Lorenzo’s method. In doing so Tomás also says Lorenzo’s writing is comparable to the very clearest visual picture from the entire history of art as understood at the period – that made by a master modelled on the Ancient Greek model of all future artists, Apelles. He does this indirectly by saying that there is a visual artist matching Apelles in the current Spanish court. This model visual artist was none other than Lorenzo’s younger brother, Juan. It would seem then that what was being urged on the court of Madrid was the excellence of a whole family as servants and artists of the court, authorised by the august example of classical Rome, itself a means of flattering and legitimating Hapsburg rule.

But there may yet be even more to draw from this fact. It seems to be established that there was an important link established in the Spanish Golden Age, and perhaps throughout seventeenth-century Europe, between the power of visual images, however artificial in their mode of construction, to make truths usually invisible on earth, accessible to human sense. These facts in themselves would build, for the purposes of art and artists, a bridge between their role as servant glorifying temporal and divine masters and a new sense of their ultimate self-importance, as an intellectual class. In what follows we shall see them named ingenios – sometimes translated as ‘wits’ but we can understand from that a range of clever truth-tellers in writing, visual arts or both. The most revered writer in the period, Lope de Vega defined both methods of communion (i used this term deliberately) as supported by the authority of antiquity, the church (using the Tridentine decrees on art as we shall see) and illustrated it by how ‘the Spanish Hapsburgs have always honoured painters’.[3] Amongst the artists Lope de Vega’s praise in his book titled Noticia general para la estimación de todas las artes (note that the same advice can be given to ‘all the arts’) is Juan van der Hamen. However Laura Bass argues that praise was in part in order to show that painting, like his dramas, were a ‘learned form of visual signification indispensable in urban social commerce’. And like his dramas too I suspect that he felt that those paintings would argue for an ideology of piety and service linked to the lower rather than the aristocratic society.[4]

In an important sense artists of the Golden Age justified the import of their service to Imperial Crown and Church as that of persons ideally placed to recommend service to authority as a value system for the nation as a whole. This is a theme we see in England under very different political circumstances in Milton’s On His Blindness too: ‘They also serve who only stand and wait’. Ingenios were indeed the ideal architects of a Golden Age of the moral imagination. To illustrate their high purpose, Ignacio Lopez Alemany, for instance, says that both visual and verbal artists (including historians) of the Golden Age were ‘compelled to “amend” the so-called “errors” to which strict historical fidelity could fall prey, because it was accepted, art could – and should – perfect nature’. He goes on to refer to Vincente Carducho, who may even have been the master painter who taught Juan van der Hamen.[5] In Carducho’s Diálogos de la pinctura of 1633 the artistic master said ‘it is a quality of the good artist to exceed the imitatio by “amending” the reality’.[6]

John Slater takes this idea further by showing that Lorenzo van der Hamen’s histories exemplify par excellence ‘the most pervasive historiographic conceits of the period – comparisons between the writing of history and the creation of works of art’ and, most significantly reveal ‘the closing distance between artistic and historiographic discourses’.[7] He later phrases this in terms I want to elaborate in terms of paintings by Lorenzo’s brother Juan. He argues that, if history is to credible to its readers or listeners, it needed:

… to reassert, rather than displace, the authority of the historian by means of visual description. In this case we find history conceptually approaching, almost asymptotically, artistic representation.[8]

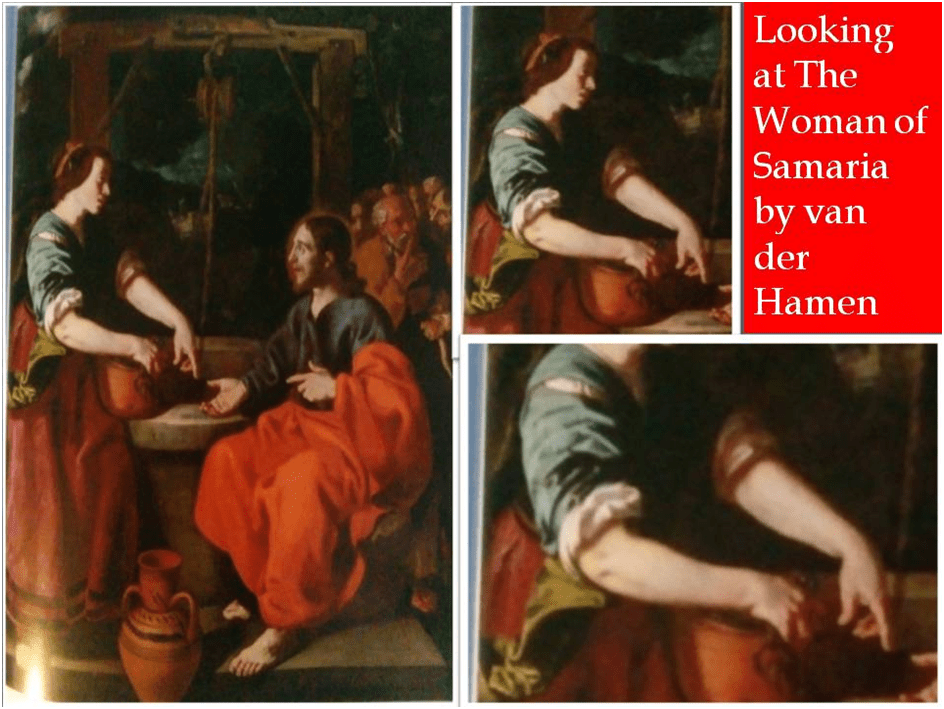

These ideas feel to me important particularly in thinking about one of the paintings attributed to Juan van der Hamen in the Spanish Gallery, Christ and the Woman of Samaria. In my opinion this picture glorifies an act of teaching and learning and the acceptance of ordained authority.

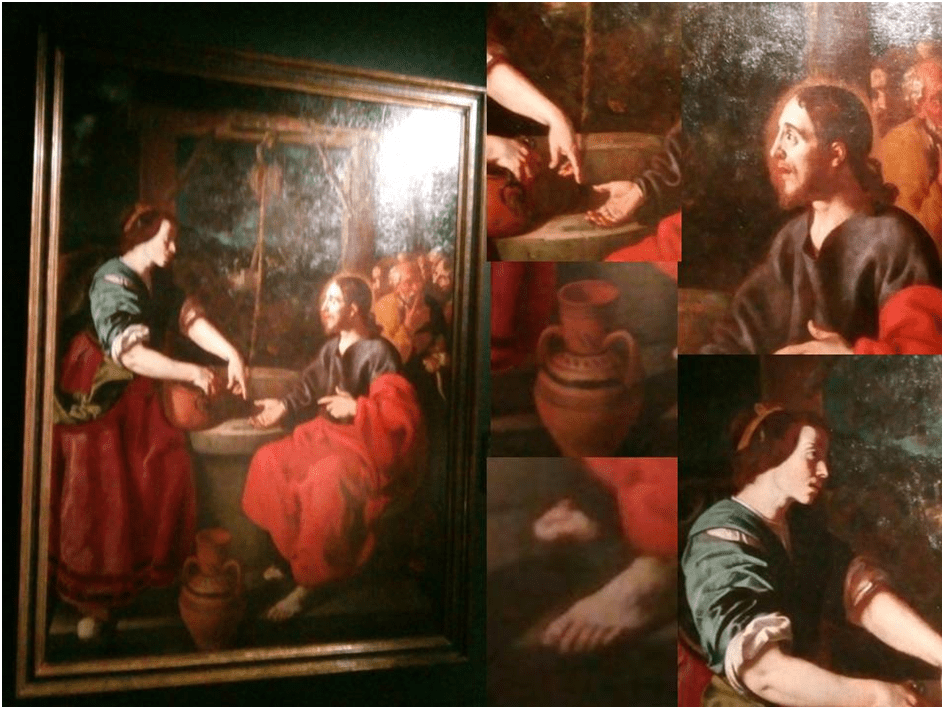

However before starting I think it is worth noting that William Jordan neither lists nor discusses this painting and I can find, with no access to an institutional academic search engine, no other discussion of that painting that confirms its attribution. I will therefore assume that attribution as asserted in Jonathan Ruffer’s The Spanish Gallery: A Guide to the Works of Art wherein Ruffer speaks of the painting ‘showing homage to Caravaggio’s tenebrism’ (the use of dramatic light, shade and shadow in picturing a scene).[9] Moreover, although Ruffer seems merely to characterise a trait of a single artist here, Rosemarie Mulcahy lists tenebrism, as well as ‘close of observation of nature’. She could have added close portrayal of objects associated with the contemporary taste for ‘still life’ I believe too. These traits are she insists amongst the tools of artistic innovation used in the ‘quest for verisimilitude’, which she also describes as ‘characteristic of much of the religious art of the early decades of the seventeenth century’. Mulcahy cites, as well as Van der Hamen, Francisco Ribalto, Bartholomé Carducho and others. The example she uses from Van der Hamen at this point in her argument is his San Isidro of 1622. This painting, which attempts to realise the miraculous in the apparently visually real, was part of Philip III’s successful (in 1622) campaign to have the farm labourer who was to become saint Isidore, and other Spanish religious, canonised as saints by Pope Gregory XV. [10] William Jordan is inclined to see ‘dramatic naturalism in that same painting, calling attention to its nearly staged effects of emphatic lighting and tableaux-like ‘stiffness’.[11]

I think both of these characterisations are comprehensible in the term ingeniosidades, used in my title, which bears the meaning the words ‘conceit’ and ‘wit’ used in England in the sixteenth and seventeenth century when used to characterise the inventive cleverness of an artist’s practice with the medium of their art. At this point, if this argument is worth following, it is useful to remember the discussion of historiography above to show that, at the time, invention was not seen as necessarily antagonistic to realistic mimesis. This is because the truth towards which art aspired was beyond common vision, and equivalent to supernatural ‘hidden’ truth. And the revealed truth of San Isidro, he was the saint of workers and labourers, was the example set by his acquiescent piety and service, though lowly (as revealed in his clothing and unshod feet. Feet are of interest here because naked feet were revered by the tremendously influential Franciscans. They demonstrated, as in Caravaggio too, the value of those who serve even from the base of society – those whom, like naked feet, were nearest to the earth.

Some of this imagery and its purpose as instructional service by a clever artist seems relevant than in that very common topic of religious painting, Christ and the Woman of Samaria.

The story the painting tell is from the Gospel of John, Chapter 4, and the International Standard Version thereof can be accessed at this link. (In case it helps the best and most comprehensive popular contemporary exegesis I could find of it is also at this link.) What is clear about the story though, however it is interpreted, is that it concerns the transmission of Christ’s teaching to those resistant to such teaching (and at the time thought least worthy of it). The teaching is modelled by Christ himself. The Woman of Samaria is an outcast. A Samaritan – an ethnicity traditionally distrusted and sometimes shunned by orthodox Jews is the first level of the otherness of this particular learner. But she is also othered by being a woman, and one, moreover, shunned by other women (why therefore she comes to the well alone in broad daylight without the support of other women – even Samaritan women). The reason for this, as Jesus predicts (or like us calculates from that evidence) is that she is a widow (already married five times) and now living outside wedlock with another man.

In my collage of details above I have tried to demonstrate some basic level of awareness of elements that are typical of the Baroque instructional story. Such stories were shaped by the regulation of Counter-Reformation Catholicism, policed by the Spanish court in Spain (employing court painters to do so) from the time of Philip II, of which this painting is an example. Alfonso Rodríguez G. De Ceballos describes for us the Council of Trent stipulations, decreed in 1563, the various criteria for such images that would certainly apply here:

They should depict true, not false or apocryphal stories; they should be decorous in nature; they should be lifelike; and their emotional and expressive qualities should inspire not only devotion but also emulation of the sacred figures depicted.

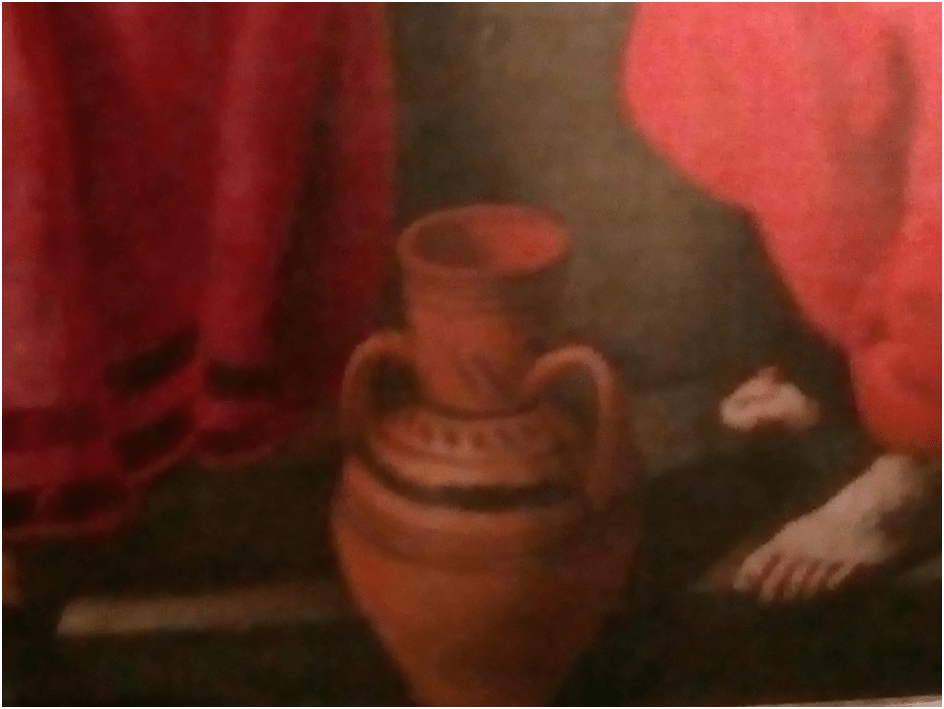

He goes on to show that the painter Francisco Pacheco interpreted especially the decree to aim for verisimilitude to produce that style of painting we now see as characteristic of them: ‘a realist style, expressed in scenes and figures that seemed to be contemporary and extremely close to the viewer’.[12] See in my details how such rigorous criteria might have been interpreted. The nearness aimed for is both perspectival and temporal, leading to the effects of both theatre and anachronism. For instance, it will be no surprise for those who know the way in which the contemporary liking for ‘still life’ became a medium for artists in imitating nature in a single moment captured out of time. There is no surprise either that an artist like Juan van der Hamen y León, known for stunning still life painting that takes up the charge of making artifice look like the real thing like the ancient Apelles, should make his religious painting a site for everyday objects too. Thus common objects in ‘still life’ painting such as decorated water jugs and pots, recognizable in the form used in daily life by his contemporaries at the base of society, appear in this painting. They appear to in contempoorary scenes in the seventeenth century such as Velasquez’s portrayal of the everyday process of cooking eggs.

Such realism – in the creation, say of a water jug like that shown here – involves the artist in demonstrating inventive decoration too, without in this case breaking from a kind of realism of presentation. Thus though this does not represent the past faithfully, and with respect to historical accuracy, it embraces anachronisms in order to make the scene recognizable to the audience contemporary to the painting itself. The pot serves another function too. It graces the picture frame level of the painting and establishes, with the step painted as if ‘behind’ it, a staged perspective of three-dimensional depth. For the purpose of creating an illusion of depth too, the feet of both figures are seen to be overhanging this step, the woman’s being shod, those of Jesus, in near contrapposto manner, naked. Those naked feet link Jesus to the woman in the same way as was signalled by Franciscan practice.

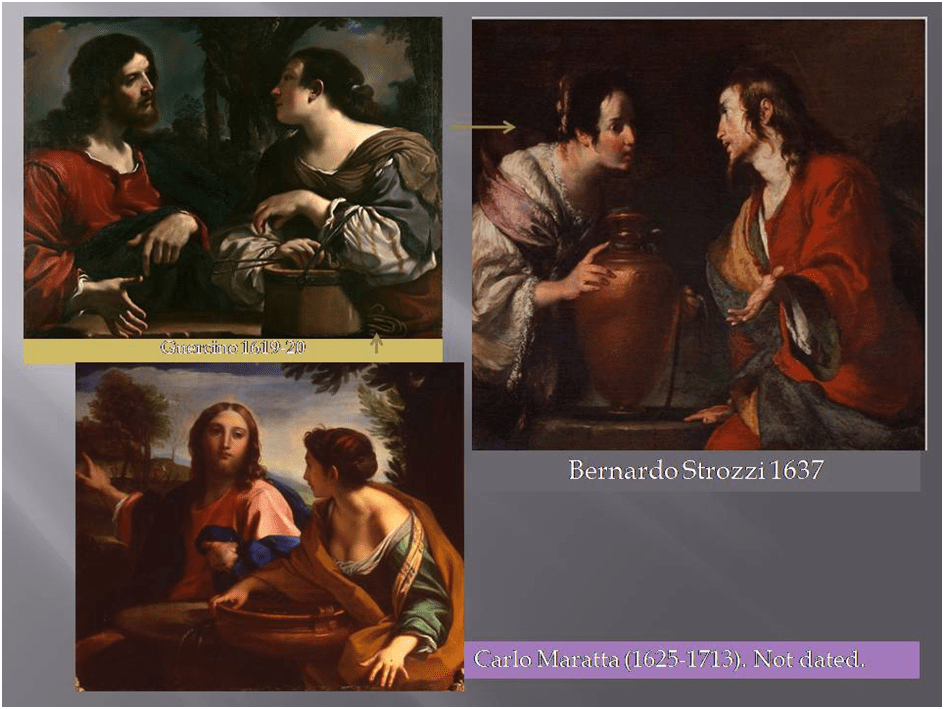

Otherwise, the realism of the painting is characterised by how the women is represented. We can emphasise this by looking at representations in other artists, particularly non-Spanish ones.

In looking at these, mainly Italian examples, we probably notice the stress on the Woman’s femininity, relative youth and the finery of her clothing. In each case her hands are featured but these are not the hands that have been marked or changed by labour. Note especially the fine, almost girlish hand of the woman in Maratta’s version and the refined femininity of the gesture of the hands in Guercino. And this woman is sexualised in each case. There is abundant visible flesh at the shoulder and neckline of all of them, compared as we shall see with Hamen’s figure. Maratta’s woman may be modestly turned from Christ’s gaze but not to that of the viewer, who has a privileged view of her breasts. When their flesh is covered it is clothed sumptuously in ways that allow the painters to display their facility with the representation of folds in what may be silk and attract the viewer’s attention in the manner that has become known as ‘the male gaze’. Such features amplify the sexuality of the woman in the Gospel, marked by her being a widow of five husbands and currently living, as Christ predicts or guesses, with a man out of wedlock. What our Italian painters have done is emphasised that sexual nature even to the point that she might not only be a ‘fallen woman’ but a prostitute of kinds.

At this point, we could look again and comparatively at Van Harmen’s woman. Compare first those muscular arms and the large unrefined hands of Hamen’s Woman, compared to the delicate hands (even when more fleshed out as by Guercino).

In contrast, as I have suggested, Hamen shows a working woman with flesh largely shown only at the rolled up sleeves and strong, almost masculine in the gendered terms often used, arms. Her face is not exhibited with the light falling on a white patch of flesh which barely forms a profile She is not there to be seen by us but to hear and receive the teaching of Christ. She is the type not of ‘a fallen woman’ but a humble learner, which will show she need not ever be fallen or seen as such. All this drama is enacted in the exchanges between the hands of the two key figures.

That this painting is about learning seems to me to be confirmed by the way in which van der Hamen locates this scene at a particular moment in the text from the Gospel of John. Related in verses (v.) 25-27, it shows the disciples returning from the city with food and encountering Jesus in conversation. The disciples are painted, as it were, as if immediately behind Jesus. Their lead member here is seen hushing the others, the visible gesture by which the disciples prohibit any address to ether the woman or Jesus (in v.27 represented by,’ But no one asked, “What do you want?” or “Why are you talking with her?”) is clearly important here. As viewers of the painting, we too are addressed as listeners to both his and her words, by this hushing, to listen for silent or subdued speech – even that in pictures.

At this point in the Gospel Jesus has identified himself as the Jewish Messiah and Christian Saviour:

25 The woman said, “I know that Messiah” (called Christ) “is coming. When he comes, he will explain everything to us.”

26 Then Jesus declared, “I, the one speaking to you—I am he.”

This then is a moment of profound teaching and learning and of transformation of Christ’s mission to which we are listening with hearing eyes. And the contested subject of the discourse of the main disputants in the painting is drawn to our attention. It is water. The woman points downwards to the well containing water. The receptacles that surround are currently empty receptacles of water – pottery of a peculiarly Sevillian character is in the forefront and prominent at two levels of illusionary depth and real height in the painting. What Christ is explaining to her is, after all, the ‘everything’ which she has waited to hear. Messianic Hope is characterised here and queried in a restless need for sustenance; like that of thirst but deeper and unrelieved. In the text of John for instance, Jesus appears to have chosen this moment to demonstrate how He must change the nature of his mission to move from the the symbol of redemption by the Baptism conducted by his servants including John the Baptist (the text even tell us that as well as John (v.4): ‘it was not Jesus who baptized, but his disciples’). The Mission is now to be an eternally fulfilled one of which water is the symbol – he and his embodied Word are ‘living water’; both teacher and what is taught.

Hence Hamen emphasises Christ as speaker of the truth of his own role (and his mouth is open to do so). Even his face and body speak with a visible aura. For clearly Christ here is also showing himself as the bringer of salvation to those not currently baptised. At no point is water actually exchanged between these two figures; although they speak of its desire. It is a moot point whether this painting emphasises, as an Imperial Power representing the Catholic Church to non-Christian populations, that the ‘desire for baptism’ (a point of contest within Catholic doctrine) might be equivalent to actual baptism in the ‘ignorant’, as suggested by the Council of Trent. But I would suggest that the painting teaches and causes us to learn about the import of desire in holy doctrine for renewal and salvation over and above the literal physical contact with water.

I am not qualified however to argue about what the message of the painting actually is. My aim is just to point to the intensity with which it emphasises the virtues of the act of teaching and learning and the desire to be taught in ways that transcend physical mere physical nature, which is particularly how the desire for baptism might transcend the act of baptism if not negate it. In a sense this emphasises the power of the human intellect in acts of communion and communication, of teaching and learning as a current reality. Lorenzo van der Hamen emphasised the incarnation of God, not only in Christ but in the Church and its teachers. This is a nod to the role of the intellectuals or ingenios of the new Spain since the only way human can see the glory of God is in ‘its effects, illuminating the world with its doctrine and fertilizing the earth with its miracles’.[13]

In effect what this painting does is incarnate such truths. It gestures to the combination in the art of the new Spain of art and intellectual ingenuity (that of the ingenios). Lorenzo van der Hamen indeed could say ‘the sum of history’ up to the Spanish Golden Age was ‘the work throughout many centuries of ingenio and art. “the two sculptors of nature” (“los dos escultores de la naturaleza”).[14] Christ and the Woman of Samaria is a work of supreme religious art, and it teaches something of the text of the Gospel but it also encapsulates the function of art to embody human intellect. Here it ultimately I think attempts to bring a whole nation nearer to God and acquiescence to a pious obedience to God and Emperor. In a sense then it it is art about the supreme import of the artistic image. It silently insists that art’s import does not lie alone in its beautiful visual effects (like that of fine clothing – though the fold of cloth is as ingenious here as in Italianate art) but those also of its exegesis as learning. Art is not just seen but is an active interactions between art as teacher and the audience as taught through recreated and imagined senses otherwise absent. I think the sum of that message to be an appropriate service required of us all.

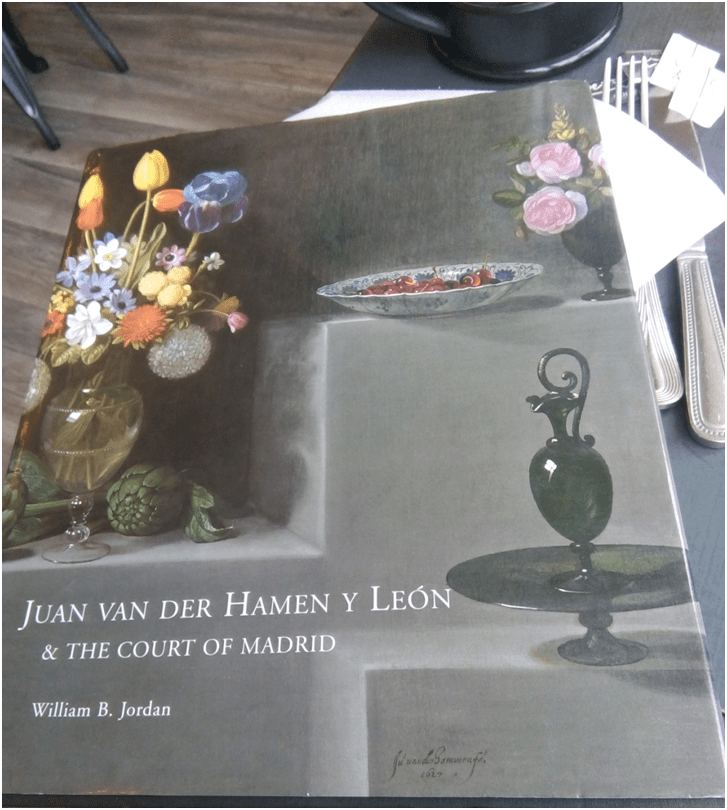

And this brings me to the other painting – one of the artist’s much more common secular subjects. His reputation as a painter of ‘still life’ has overshadowed his portrait figures. This was apparently so even in Juan’s lifetime because Pacheco says that his renown for the still life was ‘much to his displeasure’.[15] One can only hope that the fact that he is not represented by still life in the Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland might prompt some to look differently at the artist, and not just because of his jobbing work in painting clerics, aristocrats and intellectuals. When Jordan wrote his book, the whereabouts of the other painting was unknown. It is represented in that book by a monochrome photograph, which Jordan calls Portrait of a Young Page and dates to c. 1625-30. He says that, though its provenance was unknown (whose pageboy was this for instance), ‘when its whereabouts are determined, it is bound to emerge as one of Van der Hamen’s most endearing works’.[16] I will finish with looking at it under its present title Portrait of a Young Boy Holding a Lance. This title may reflect the view internally floated in the Spanish Gallery by the Curatorial & Research Associate of the Spanish Gallery, Morlin Ellis that this young man is too richly clothed not to be of a fine family and may be a son of the Portuguese Da Silva family [see https://spainculturescience.co.uk/the-auckland-projects-spanish-gallery-appoints-new-curatorial-team/ for source] Whilst documentary evidence may not yet be available, Ellis’ qualification to hold such a view can be intuited from the fact that, after her former teacher Professor Nigel Glendinning asked her in 2010 to join the committee of the charity ARTES, which promotes the study of Iberian and Latin American visual culture, she chaired it from 2015-17. It certainly complicates thing for my reading that this new title, and the discussion behind it, no longer identifies the boy as a servant, yet even so the attitude of waiting on service is evident even if this boy is enacting a role either ceremonial or military and the notion of the aristocratic courtier as entitled servant is particularly appropriate to the Hapsburg domination of its aristocratic otherwise overmighty subjects in the Golden Age.

Endearing this portrait certainly is. It is so, in the same way as when children are even today cajoled to take up idealised adult roles. And the role here is that of standing to attention, with intent to be active to serve shown particularly in the attitude expressed in the hands, which hold both lance and sword handle in quiet (but not impatient) readiness. The same attitude might speak from the eyes. These are not servile but they are attentive – listening for a word of command. I certainly feel that these complement the idea of the artist’s role as the producer of images of contented service but almost make a claim for grandiose artistic design and impression. They flatter the artist patient enough to reproduce them. Like Jordan it is difficult to be specific because the intentions of the portrait of are lost. Is this the role-playing son of a rich man or a rich man’s page. This would help us to determine a reading.

I would still say that the subject of this painting is a mix of the attitude to both service and hubris that ought to characterise art and artists, for only they will capture the grandeur of passing times eternally, or longer anyway than any one period of history.

This is then all I have to say about this painter. My next blog in this series will concentrate on another painter as represented at the Spanish Gallery. If I am bold enough at that point it will be El Greco.

All the best

Steve

[1] The Latin is from Horace’s Epistles (Book 2, Epistle 1, ll. 237 -239) and is that, in English, italicised in the quoted translation following: ‘That same king, who paid so enormous a price for such / Ridiculous poetry, issued an edict / Forbidding anyone but Apelles to paint him, / …’ Otherwise this is by Tomás Tamayo de Vargas, ‘the royal historian of Castile’ cited from the preface to Lorenzo van der Hamen’s Don Felipe el Prudente (1625) cited by William B. Jordan (2005: 67) Juan van der Hamen y León & The Court Of Madrid New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

[2] Ibid: 69.

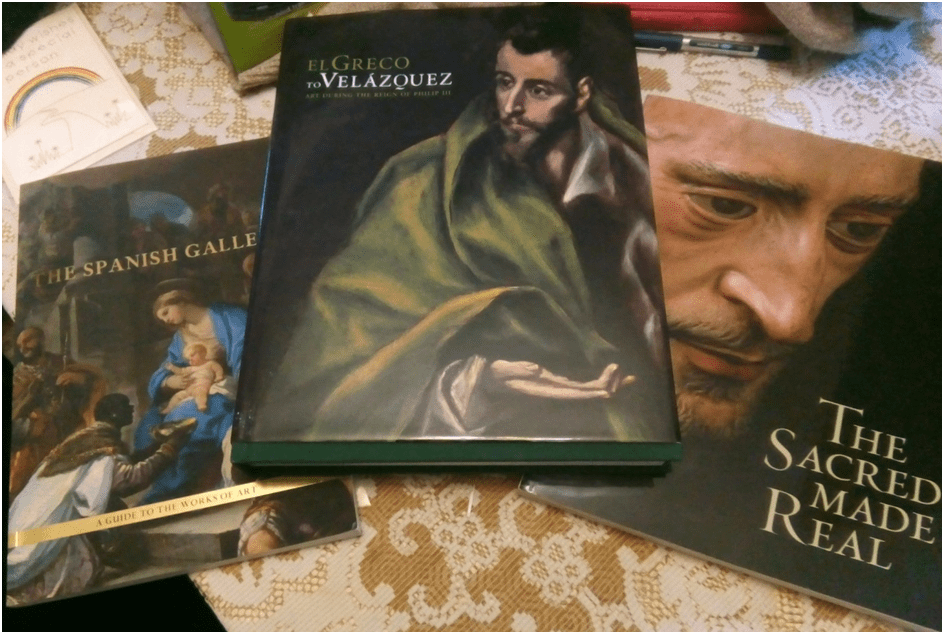

[3] Laura R. Bass (2008: 166.) ‘The Treasury of the Language: Literary Invention in Philip III’s Spain’ in Sarah Schroth and Ronni Baer (Eds.) El Greco to Velasquez: Art during the Reign of Philip III Boston, Muuseum of Fine Arts Publications. 146 – 181..

[4] Ibid: 167f.

[5] See ibid: 51

[6] Ignacio Lopez Alemany (2008: 103) ‘Ut pictura non poesis. Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda and the Construction of Memory’ from Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America, 28 (1). 103 – 18..

[7] John Slater (2007:218) ‘History as an Ekphrastic Genre in Early Modern Spain’ in MLN (122) 217-232

[8] Ibid: 220

[9] Jonathan Ruffer (2021: 60) The Spanish Gallery: A Guide to the Works of Art Bishop Auckland, The Auckland Project.

[10] Rosemarie Mulcahy (2008: 144f.) ‘Images of Power and Salvation’ in Sarah Schroth and Ronni Baer (Eds.) El Greco to Velasquez: Art during the Reign of Philip III Boston, Museum of Fine Arts Publications. 123 – 146.

[11] Jordan op.cit: 64.

[12] Alfonso Rodríguez G. De Ceballos (2009: 49) ‘The Art of Devotion: Seventeenth-century Spanish Painting and sculpture in its Religious Context’ in Xavier Bray (Ed.) The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture 1600 – 1700 London, The National Gallery Company with Yale University Press. 45 – 58.

[13] Translated (Spanish is in a footnote) and cited from Lorezo van der Hamen Al hijo Segundo de María Santissima, al solo en sus regalos y favores, a san Juan Evangelista in Jordan op.cit.: 136.

[14] Ibid: 168, citing Lorenzo’s 1625 encomium to Don Felipe El prudente.

[15]Cited Ibid; 147

[16] Ibid: 199

One thought on “‘Ne quis praeter Apellem Pingeret / For his ingeniosidades are not inferior to those that antiquity celebrates from the palette of that artist’. ‘A Young Boy Holding A Lance’ and ‘Christ and the Woman of Samaria’: Two paintings by Juan van der Hamen y León (1596 – 1631): Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland: Reflections and Discussions in my free time on some of the Paintings, as part of a personal learning project related to the Golden Age of Spanish Painting. (No.1).”