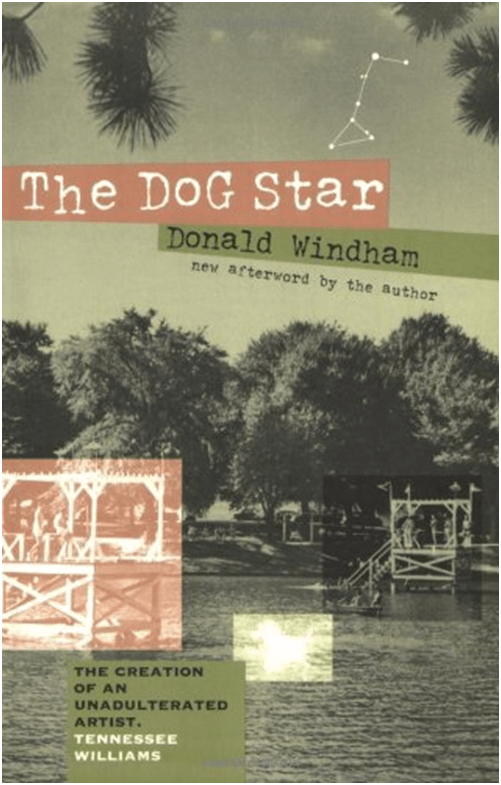

In the 1998 Afterword to his first novel, published in 1950 Donald Windham says: ‘my ideal was that the theme of a novel should never be stated in so many words, only by the novel as a whole’.[1] Is there an advantage to queer novelists writing in an age that oppressed queer identities of writing indirectly by never stating directly that the novel has a queer theme? A reflection on reading the Donald Windham’s reprinted The Dog Star, (1998, first published 1950), published in Athens, Georgia, by Hill Street Press, LLC.

In 1998 Donald Windham said that, although the most important objective of his life was ‘to live the way I wanted to’ rather than a desire ‘to write’ and be a recognised writer, both objectives were connected. To write though about life as a queer man seemed in 1950, for a debut novel at least, to be an impossible task. Windham argues that already, in 1950, he had however ‘become convinced that, in fiction, connotation is stronger, and wears better, than denotation; my ideal was that the theme of a novel should never be stated in so many words, only by the novel as a whole’.[3] We should note, of course, that the tenses of his verbs here declare only that this was a past ideal and one not necessarily continuous with his present thinking. But a puzzle remains. Can fiction that conceals from open view or disguises queer themes, such as in the novels of E.M. Forster (whom Windham knew, met, corresponded with and admired) have the possible advantage of strength and endurance as fiction, akin to that of Forster across the English-reading world, over ones with more open themes?

It’s this question that I want to look at in relation to The Dog Star, before launching, as is my intention, on a longer blog on Windham’s novels, for which I need to read much more. For, in my view, The Dog Star is an incredible novel (regardless of being a debut) that relates contemporary constructions of masculinity to categories we today identify as sex, gender, sexual orientation, the nature of desire and self-care. These themes, none of which are specifically about queer life alone, are, however, related within a complex web of interactions that ensure that when one of these themes is queered that all of these concepts are simultaneously queered and queerly related.[4] In the process this first novel by Windham gave, I would argue, a new way of talking about male concepts of ‘juvenile delinquency’, suicide and criminality which were highly current in the 1960s, maybe even taking on the role of triggers to ‘moral panic’. Yet, as Windham tells us, the UK publisher Doubleday accepted the novel precisely because they read it as ‘fitting in’ with that popular and topical theme,

Looking at the phenomena of concern with the violence and self-loathing of young men and boys in civil society and government nowadays it is easier to see the social issues as socially and ideologically framed. They were (to repeat myself more fully) prompted by a moral panic about the fate of young working-class males after both World Wars.[5] Out of these concerns were to spring pathologising frameworks for understanding the ‘issue’, particularly those related to infantile experience of maternal deprivation in the work of British psychoanalyst John Bowlby. Indeed Windham almost predicts the use of such theories in his novel by giving stress to the ‘inadequacy’ of Blackie’s mother and Blackie’s socially inherited resistance to values perceived as ‘feminine’. ‘Sissy’ is a key word in the family and peer group cultures as a means of defining the contrary of a desirable masculinity for boys in their appearance and behaviour. The decay of values that sustain a notion of motherhood and motherhood charged with the task of loving, protecting and socialising the connection of loving and protecting reoccurs as a theme in relation to many young women in the novel such as Mabel (Blackie’s casual lover and clearly an absent mother to her own child to an absent husband) and Gladys, Blackie’s sister.

However, the treatment of the theme is not the only possible determinant of Blackie’s mental state as it is described in the novel. It is a mental state that will lead him to suicide (the novel opens and closes with significant suicides by young men) but raises more general concern relating not only to the absence of ‘mothering’ in Bowlby’s term but with with other social failures: in youth social and criminal care institutions for instance, as well as ignorant families, unsupported by the state or other caring umbrella institution. Without this general belief that might shape the expectation of young men by educating them into appropriately emotionally literate lives regarding relationships (a role which after all we might expect the novel as a force of social learning to take on), the acting out of relationships by boys, whether with women and other men, in this novel, is palpably shown to be lead to lives starved of fulfilment and the ability to give and receive love. The core flaw in the young men in the novel is that love and care of another is always seen by them to be suspect. However important then that it may be for boys to learn to be wary of the approach of others, in this novel such extremes of wariness and lack of trusting attachment are demonstrably weaknesses rather than strengths. The novel therefore imagines a world in which the one outbreak of trust in Blackie as a teenage boy is rendered ineffective by his own incapacity to risk the expression of his love to another, in this case his role-model hero in Borstal, Whitey.

The idea of boys unsupported by overly heteronormative binaries of sex/gender is also suggested to be in part autobiographical in the 1998 ‘Afterward’. Here, Windham gives guarded reference to ‘Fred Melton, to whom the book is dedicated’ as giving to him the idea of the story as based in the latter’s admiration for his ‘dead brother’. If we are to take this hint seriously it would suggest that Fred is the model for young boy the novel names Caleb. Caleb is the younger brother of the novel’s main focus of attention, Blackie. But there are other reasons why Fred Melton is honoured. In the Afterword these reasons are stated in vague and rather abstract terms: for instance, the writer tells us that Melton gave Windham the capacity ‘to leave the world I knew, the future I foresaw for myself in Atlanta, and to be responsible for my life and things’.[6]

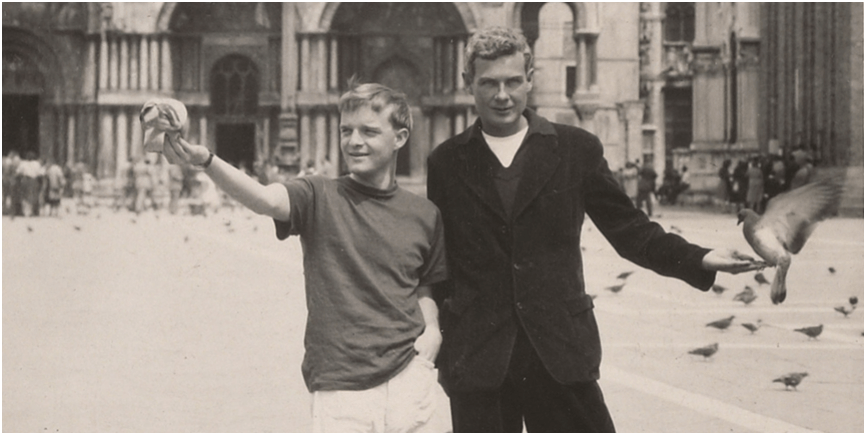

What is the reason for a dedication so significant in terms of Windham’s own life but yet also so abstract? In 1942, Windham continues, Melton, a New York silk-screen artist and later photographer was in the armed services, married and his wife expecting her first child. By 1998 we learn moreover Melton has two grown boys, one of which was that expected child. Yet Melton’s enduring heteronormative story ending is ambivalent given Windham’s attribution of so much importance to the way his own life was to be conducted, which was as a queer man. By this time Windham was partnered to actor, Sandy Campbell, whom he met in the preparation of his co-authored play (with Tennessee Williams) entitled You Touched Me which played in Broadway in 1945. By then Windham was preparing for life in Italy, thought to provide a freer environment for queer lovers. The reason for the vagueness of the reference to his debt to Melton may relate to the fact that we now know that Windham had gone to New York in 1939 (Windham being born in 1920 was 19) to live with Melton as his first serious and long-term boyfriend, and together they met, lead by Fred, the New York circle of queer men who were to determine that future.

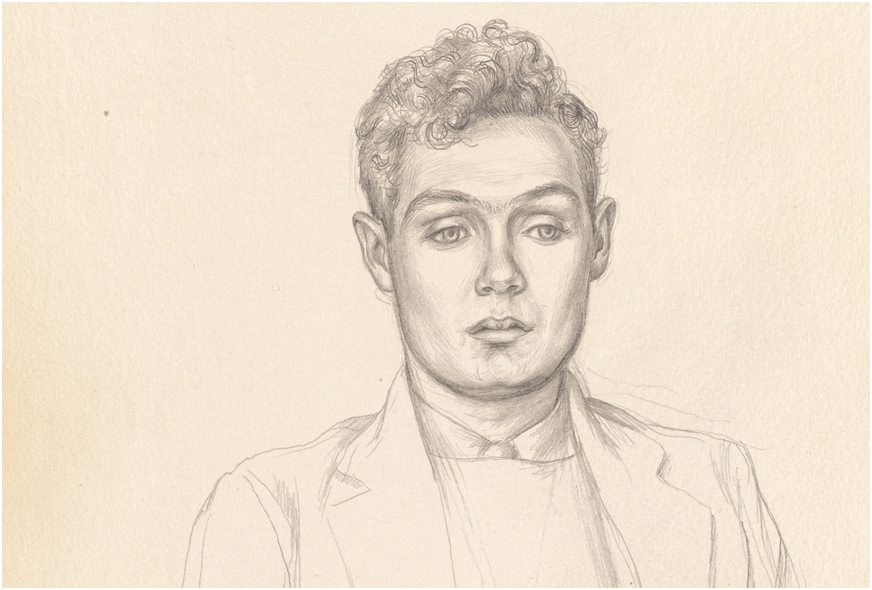

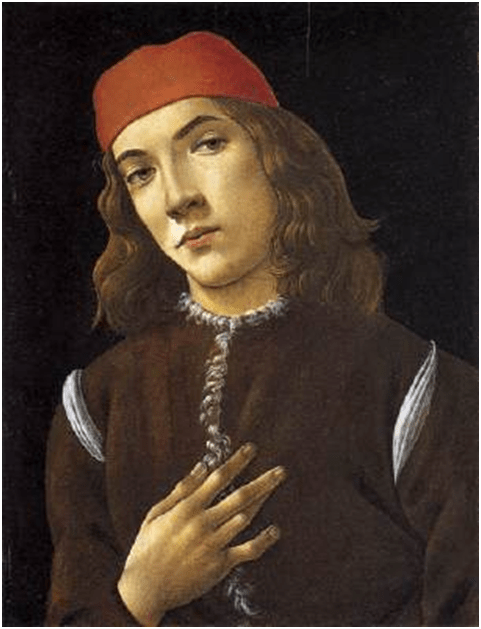

Melton, despite continuing his life with other male partners, was, unlike Windham, to return from, in public at the least, relationships with other men from the fully heteronormative future he was now living, but which he had helped Windham to avoid.[7] It is very easy then to infer from such indirection of approach to the themes of how a queer life, relatively free of a rigid heteronormativity that it was oppression alone that explains Windham’s careful excision of direct reference to queered sexualities in his debut, especially given its greater visibility as a choice in later novels, including Two People in 1965. Meanwhile Windham became part of a group of highly cultured queer men, and some women – Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein for instance – who took each other’s lives a template for a queered reality. These lives, with some reference to Windham, are explored by David Leddick (who knew them all) in his Intimate Companions: A Triography of George Platt Lynes, Paul Cadmus, Lincoln Kirstein and Their Circle. Paul Cadmus, in a drawing owned by Yale University Library drew Donald as the type of curly-headed young man-boy, knowingly sexual beyond the conventional ideas about his age group as signified by lips that might have come from a young man in Italian Renaissance paintings Cadmus modelled himself upon, but with eyes that express something very vulnerable. I think of Botticelli’s young men.

The Dog-Star however, as we have seen, was read, at least by those who refused to see any other way of comprehending the plight of boys’ transitioning to ‘manhood’ branded across their head as the tendency to widespread ‘juvenile delinquency’. The novel itself shows some awareness of Freud’s constructions in Chapter 7 of male sadistic violence in its use of the content of ‘several violent dreams’, for instance, to symbolise it and link it to Oedipal adoption of a passive sexual attitude to father figures.[8] Indeed that long exposition of the manifest content of those dreams he refers twice to a fantasy of the punishment of ‘a child’ that might, in the usual displacements of dream work in Freud, be his own repressed fantasy of passive pleasure inflicted by parental authority and by Freud connected to the aetiology of sadism, that is not manifestly sexual in his seminal paper of 1919, A Child is Being Beaten.

This paper demonstrates characterological (manifestly non-sexual) behaviour traceable to an underlying erotic, Oedipal-engendered beating fantasy: …

….

The boy evades his homosexuality by repressing and remodeling (sic.) his unconscious phantasy; his later conscious phantasy shows a feminine attitude without a homosexual object-choice. [9]

Blackie’s dream reprises elements of a similar fantasy in which; ‘A child was hurt. … Mooooottttthhhhher. A child was hurt somewhere’.[10] If this does refer to the Freudian paradigm, it would coincide with Blackie’s bullying of his brother Caleb for seeming a ‘sissy’ in his behaviour and language.[11] There is a kind of inverted constant fear, turning into violent assertion sometimes, in Blackie that he too might be supposed a ‘sissy’ or feminine in look, appearance, behaviour or language and his punishment See, for instance the firmness careful assertion of the masculine attitude in defence of a ‘compromise formation’, as Freud would have called it, of wearing a token of his female sexual partner, Mabel’s ‘softness’ as a way of reinforcing to self at least his internal conception of his ‘hardness’:

… All her features were softer and the need of her softness for his strength seemed to have softened her eyes.

But he did not forget to chronicle her weakness against her as he told him what he wanted.

-Only maybe you think wearing a bracelet is sissy, she said softly.

-There won’t be anything sissy about my wearing one, he answered firmly.[12]

I have italicised the words in the drama and third-person narration, from I would say Blackie’s point of view of things, of the narrative here that emphasise the work that goes into the constant interplay between firmness and the need for softness, or acknowledgement of some passivity thought of as weakness, in the young male. Forming such attitudes is hard work, whether or not you accept any underlying reference to the Freudian paradigm. I need to emphasise that I am not arguing for the validation by Windham or myself of the Freudian explanation of repressed ‘homosexuality’, but for an acknowledgement that the masculine fights to establish an image of itself that is not ‘queered’ (or made strange to itself) because it is much more complex a formation of sexual and characterological attributes that it chooses to acknowledge. After all, in the end, development battles, as Freud did not emphasise enough (because of the privileging of the Oedipus Complex for multiple reasons locked in his own depth psychology), is the primal one against the child’s instinct to ‘polymorphous perversity’ (a bad name he chose for infantile openness to pleasurable sensation across the somatic field that is not specialised to the genitals and which requires us to rethink what we mean by ‘sex’ as an activity).

In Blackie’s view he bears ‘wounds’ which he must not look at in a mirror or acknowledge after being beaten physically by other boys. These wounds were:

like the disfigurations of a disease and age which, if he looked at them, would betray him to himself in a bit less surety of walk as he entered a room … or in the expression of his eyes as he looked at the brothers or the men at the Cuban villa and wondered, as though he were a weak woman and could only wonder about such things, if they were his assailants.[13]

The otherness young men fear is both the scar of external ugliness and internal weakness that is reduced to merely passive behaviour, such as merely ‘wondering’ about events, and the symbolic signs of that otherness is those intersectional identities to which even men are prey of looking, feeling (because they will eventually be) disabled, ill, old or, perhaps worse, a woman – all of whom have for him the mark of being not-a-man rather than having validity in their intersectional potential, perhaps for all of us in some degree or other – even, let it be said the ‘wound’ of passive femininity as the culture of this novel perceives it and holds out to our critical gaze as readers to challenge or accept.

To his mother Blackie claims he is in his teenage, ‘as much a man as I’ll ever be’.[14] Yet it is not only the latter who challenges Blackie right to hold that status. Mabel accuses Blackie of merely ‘acting the tough guy and it don’t fit you’. Worse she locates the weakness in the capacity of someone it’s ‘fun to make love to and because you’re full of feeling for a boy. I’ve never known anyone so full of feeling’.[15] The opposite of accepting that vulnerability and fullness of feeling is for Blackie, and the generation of young men in the novel, the pursuit of a heroic status long consigned to fable or the cinema screen, the thing Blackie thinks he sees in Whitey, a young man whose external show is all there is and which yet has a meaning Blackie seeks but cannot find. That show is summarised in a phrase that passes for a sentence in this novel, for obvious reasons, it is without discourse of reason or emotion: ‘Strength, courage and indifference’.[16] Those ‘virtues’ are fugitive in a family but ever-available in a reform school in which boys learn to fight for what they have.[17] Sometimes people fail even to notice them.[18] It can be in fact only realised in dreams and that is why the novels contains many such, where it takes obscure abstracted form as ‘the desire for great actions like those in his dark imagination’.[19]

Whitey’s inexplicable suicide opens the problem and remains the problem whose solution is hunted for in the novel and never found, though those metaphors of hunting, seeking and finding resonate symphonically throughout the novel.[20] What you seek is not always, perhaps never what you find in the brightness of day only in the ‘dark imagination’ of a movie theatre or, and the suggestion is hidden in the following extract, the fate of Actaeon capturing sight of the true beauty (Diana) he desired but MUST not know – in my certain view that is the prohibited pleasure of Whitey’s beauty.

His conception of Whitey was larger than reality, but it lacked detail. In his eyes, Whitey had been able to do no wrong but he was not quite sure what whitey had done. He had pursued his hero with his senses, as the hunter pursues with dogs to get nearer to the animal nature of the creature he hunts, and he had captured Whitey with his eyes. But he had not abstracted the qualities which made him think Whitey admirable. Now he could not find words to recall those qualities to his satisfaction. Whitey had been strong and great and he had cared about no one. … He wanted the words to bring to his mind the feelings of power and happiness Whitey’s body had brought to his eyes …, and as he recalled Whitey’s image he repeated the words over and over until they absorbed from the image the meaning he wished them to have. … he had seen something which is seldom sought and seldom seen by those who seek it – but it was gone now and the fate of the hunter is determined not only by what he seeks but by what he finds.

His imagination could go no further.[21]

But it is no use saying that such a passage – and you need the bits omitted by me too – can be merely translated in than expression of repressed homosexual desire, for the beauty of its queerness is that it will not allow us to think in simple binary terms – male or female, straight or gay, self and other – but forces all those terms to interact to produce the formations which make up the range of queer configurations between bodies, objects, minds, feelings and more evanescent entities that make up the range of sex, love – the range of desire and its exchanges.

And Donald Windham can do this precisely because he has been prohibited by the repression of queer themes from stating his theme directly. In an important sense Windham has taken on the creative embodiment as a writer that Blackie aspires to as a sexual presence, determining that though the sexual dance of boys and girls, men and women which is symbolised in the party to which he takes sister Gladys as her chaperone may absorb his longing for some goal he seeks it is not what he finds there and attains grandeur not by ‘great actions’, as he hoped but by passive ‘waiting – just as Windham must wait for his sense of beauty to be realisable in human form and interactions – for him male form and male-to-male interactions.

His feeling of waiting, the gulf between what he sought and what he found, coloured the whole party. …

… . Like a man in a foreign country the language of which he does not understand he impressed them with his mere presence. The impression he strove to make was not the same he made in the dance hall earlier in the dog days, but cruder between the despotism of distance and waiting.[22]

Such intense and abstract prose – delineating what is not more than what is was not liked by all and perhaps this continues to be the case. But, for me, it remains the queer prose per se, one which opens up all events in the world and imagination thereof one might wish to describe and all effects one might want to make as an artist while recording the constant compromises with which people make do in the world at is and must be until we see it change. Our only strength lies then in patient waiting perhaps or, if you are Caleb and not Blackie, seeking a new life if you can. For the only ‘great action’ Blackie is left with is either criminal, sexually violence against women or suicide. He, like whitey, will take the latter. This is the fate of the repressed homosexual, rather than the queer which is multiform and adaptive if not either free from some of the pain of exclusion. Windham sums it up in Blackie in two sentences one yearns to know how to write thus simply. He is talking about Blackie remembering coming back from school after Whitey’s suicide: “Then he had been almost afraid to see anything outside himself for fear it would make him cry. Now he defied anything to touch him’.[23] For, the noli me tangere practiced by the male ideal of the mid twentieth century is often associated with a dismissive attitude to attachments, but it needn’t be because of a dismissive primary caregiver as Bowlby insisted but by the failure of education in enough emotional literacy to understand the needs of bodies, minds, and emotional attitudes to find adequate and appropriate expression – appropriate to consenting persons of informed capacity rather than some social or cultural prescription from the past.

We need to touch each other more with informed consent and not to fear the consequence when such consent is mutual to some social ideal not of our own making. I love this novel for similar reasons to those of E.M. Forster that it is about the full perplexity of what it means to feel ‘warmth’. Let’s understand that.

Watch this space for future blogs on Windham’s splendid work.

All the best

Steve

[1] Donald Windham (1998: 225) ‘Afterword’ in Donald Windham (1998, first published 1950) The Dog Star Athens, Georgia, Hill Street Press, LLC. 223 – 226.

[2] Donald Windham (1965) Two People London, Michael Joseph.

[3]Windham (1998 op.cit): 224f.

[4] Indeed I think this is so even in more clear expositions of issues of identity relating to queer sex and attraction in later novels, such as Two People, or the short story The Warm Country, but that issue is for exploration in my second blog, following more close reading of those novels.

[5] A good starting point for this theme is in this short blog: The Western World Loses a Generation | off the leash

[6] Quotations in this paragraph from Windham (1998 op.cit.: 224)

[7] For more, if limited information, see my source available at: https://www.nypl.org/blog/2018/01/26/finding-frederick-melton

[8] Windham (1998 op.cit.: 174)

[9] For a simple set of ample notes on this, used for her university lectures, try Judith Hamilton’s set available at: “A Child is Being Beaten” (judithhamiltonmd.ca). The quotations here come from that webpage.

[10] Windham (1998 op.cit.: 176)

[11] Ibid: 47 when Caleb uses the feminine word ‘beautiful’.

[12] My italics Ibid: 96

[13] Ibid: 177

[14] Ibid: 64

[15] Ibid: 101

[16] Ibid: 56

[17] Ibid: 69

[18] Ibid: Caleb 142,

[19] Ibid: 57

[20] See for instance ibid: 46, 117, 144, 173, 154f, 190, 211.

[21] Ibid; 45f.

[22] Ibid: 190f.

[23] Ibid: 180

One thought on “In the ‘Afterword’ to his first novel, published in 1950 Donald Windham says: ‘my ideal was that the theme of a novel should never be stated in so many words, only by the novel as a whole’. Is there an advantage to queer novelists writing in an age that oppressed queer identities of writing indirectly by never stating directly that the novel has a queer theme? This blog is a reflection on reading the Donald Windham’s reprinted ‘The Dog Star’.”