LONDON ART BLOG 4: Speaking of the way in which Jock McFayden uses paint to indicate his range of subjects, which (whether landscape, buildings or people) are all facing possible extinction, Rowan Moore (2019: 48) says of the paint once applied: ‘While it passionately wants to be something or make something, its grip on the surface of the canvas is provisional’.[1] This blog reviews an unexpected look at the short exhibition of Jock McFayden’s work, Tourist without a Guidebook currently at the Royal Academy.

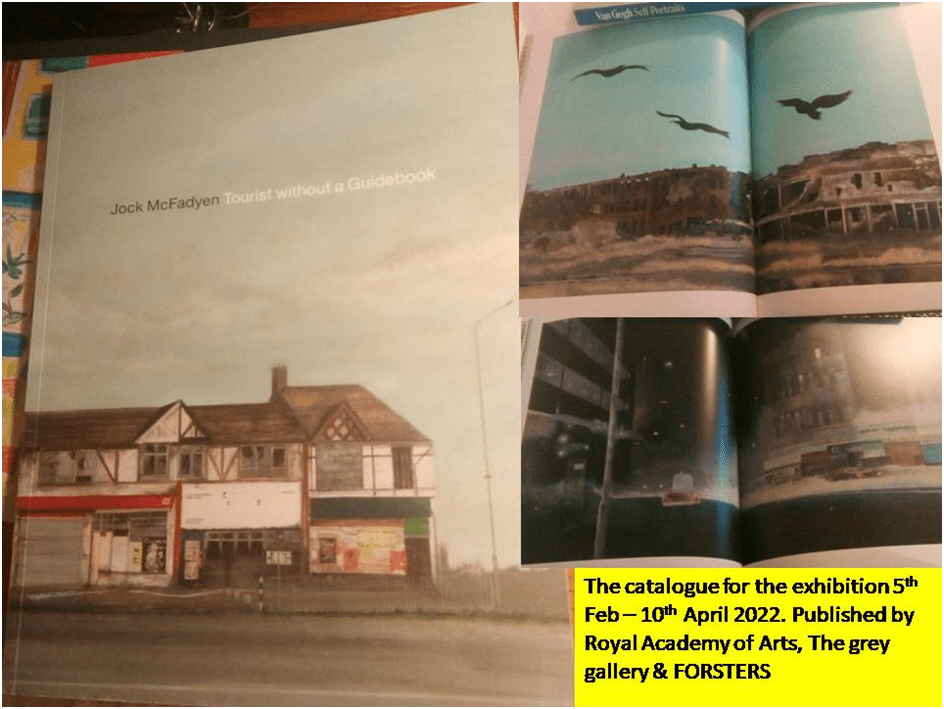

Sometimes we have to be reminded that visiting art is costly. I had intended to supplement this blog by visiting the retrospective of Jock McFayden’s work just drawing to its end at the Lowry Gallery in Salford Quays (see link for more information at the Lowry website). But this was not possible. Rowan Moore would convince me that McFayden was well aware of the fact that art has increasingly become ‘monetised’. He discusses this in an excellent chapter on the concept of ‘value’ in art in his monograph on the artist wherein the artist, whilst wryly reminding us, that art today may wish to ‘compelling description of the grim realities of life’ is still also, given that is an expensive commodity ‘being posh furniture’.[2] Now while I could not even contemplate making the purchase price of an original McFayden piece, it comes hard to realise that on a very limited pension and depleted redundancy payments, affording the return train fare to Manchester has to be budgeted for in ways that make this spending sometimes impossible. For some the mechanisms that make art the possession of an elite run even deeper and grimmer. In fact I feel ashamed that it took dear and loving friends who know my politics to be on the left to remind me that it is obscene to complain about not being able to visit art when many children and adults are homeless or unable to heat their homes or eat adequately or at all.

The Royal Academy Exhibition is a small but intensely satisfying one since many important works could be seen: enough to make me feel I had been properly introduced to the work. This matters because this art is very frankly ‘painterly’, by which I mean it is highly self-conscious of its material as paint, such that it and the way it is applied becomes itself part of the subject-matter of the painting, interacting with the mimetically represented subject matter, which is sometimes often a scene we would not in everyday life seek out as matter for observation. Indeed his friend, and a writer I love, Iain Sinclair, called him ‘the laureate of stagnant canals, filling stations and night football pitches’.[3]

But, be that as it may, Rowan Moore shows that often the painting emerges from exploiting the qualities of different kinds of paint when used together, when one dries more quickly for instance, or colour qualities such as relative opacity and transparency, thinness or thickness. And beyond this the painting emerges too from the different ways that paint might be applied, rarely does it seem by a conventional brush, by rolling out, dribbling, scratching on with a stick or exploiting coverage by paint that is patchy or uneven. The key work for seeing how this forms a painting was in the exhibition and is named Tate Moss after some of the graffiti on the abandoned and derelict building. Moore cites McFayden as saying, for instance of the bricks in the painting, which he did paint more traditionally: ‘I was trying to make bricks but also like the paint is having a good time. It’s got to feel like paint as well as feel like a damn building’.[4]

When describing this painting directly Moore speaks of the way paint refers to itself and to qualities it represents, sometimes being consciously self-referring when a painted mark can be nothing but what it is, unrelated to any represented thing such as the squiggle of paint at the bottom of the third window from the viewer’s left or the roughly applied marks in the top window above the light-blue door. Many of the marks represent paint used to mark the building such as the letters (IDS).

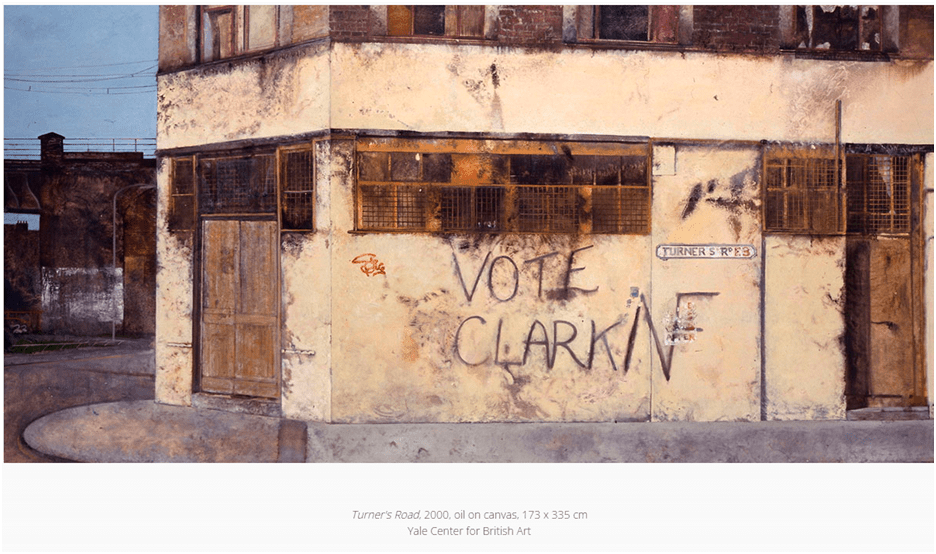

Is such a painting about the dereliction of place, the waste of scarred lives that once worked in such buildings or the bored youths who ‘vandalise’ it? McFayden both refuses to say and seems to insist that he paints only when visually stimulated by an effect in the scene he surveys: ‘an interesting vertical or an exciting shadow’.[5] Sometimes there is a political charge in what is seen that might make us think that this is the point of the picture, such as when dereliction is observed painted over by Fascist graffiti, in a painting unfortunately not in this exhibition, Turner’s Road (2000).

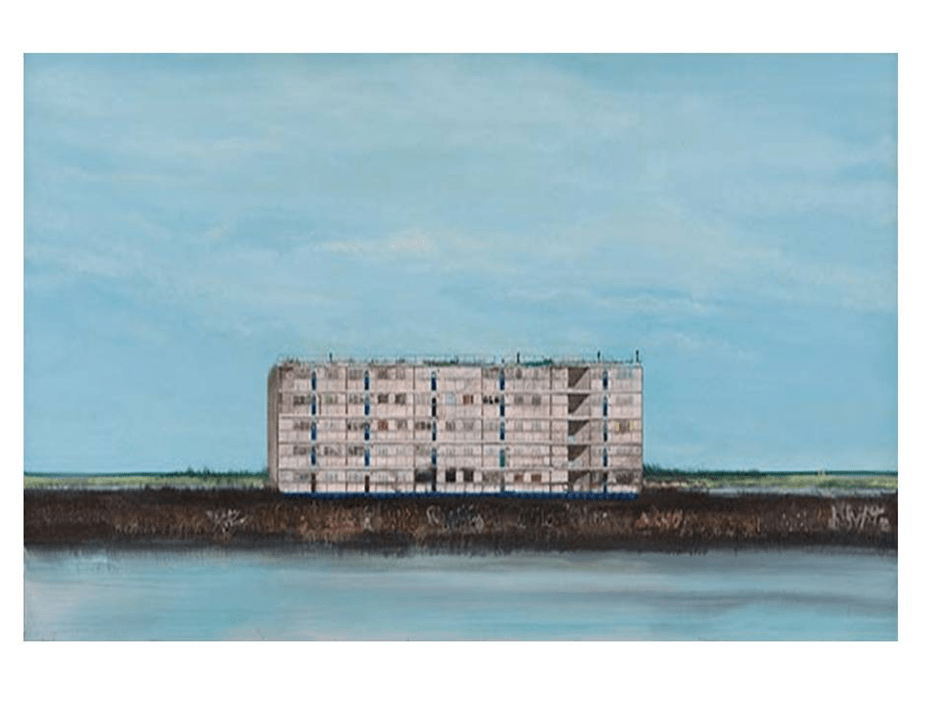

McFayden also paints figures. Often these are dots on his landscapes but not always, when he paints them as caricatures or grotesques and without any realist purpose. I have not really grown to like these but perhaps had I seen the Lowry retrospective I would be better informed. For me, the great paintings are those in which people are intuited, sometimes as absent other than as memories. It is likely (and it certainly is the stuff of an academic research report I am not interested in writing) to plot the relation of McFayden’s urban imagery with the fate of psychogeography as a movement, from its highly politicised forms in France to those more literary but still socially critical ones of Iain Sinclair. Moore’s notion that McFayden’s landscape and building paintings link the human figure to them through a common experience of ‘clinging on, only just surviving, somewhat resigned to their fate, but still seeking scraps of pride, love or desire’.[6] Here is the 2006 Pink Flats.

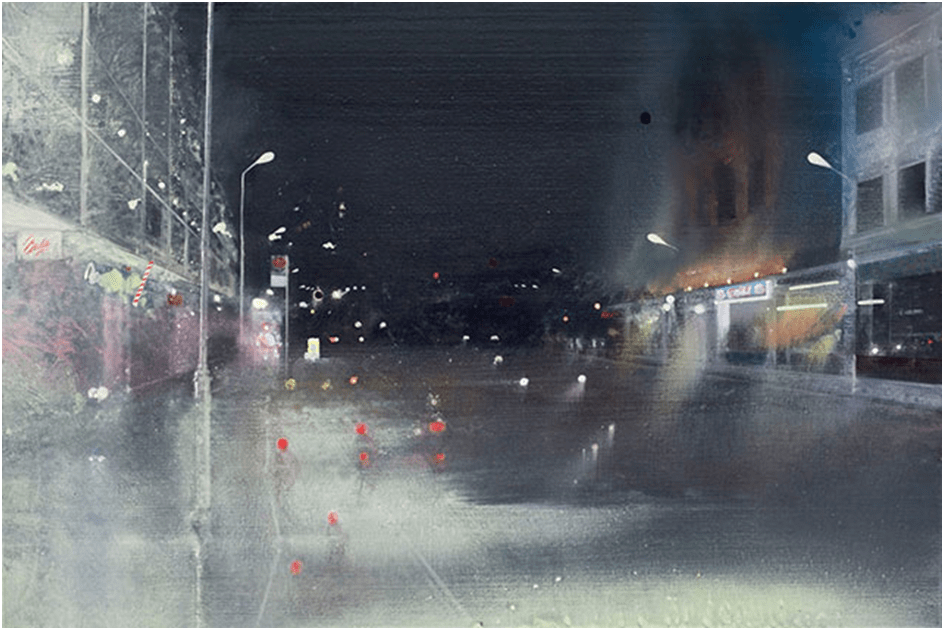

They seem otherwise isolated from that function or on a ‘road’ (often literally according to Moore) that leads nowhere very different or very particular. Here is the 2007 Roman Road.

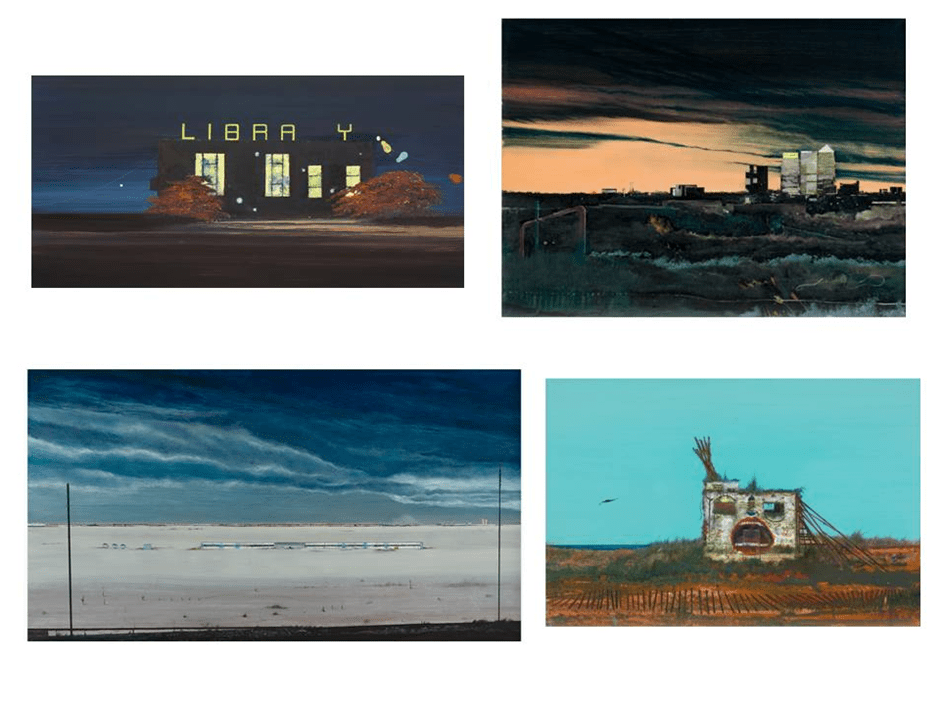

These buildings have lost even their name in the case of LIBR_RY. Some houses have human features as graffiti. Here is a collage of others in illustration of that point.

See at least one Jock McFayden exhibition if you have a chance.

All the best

Steve

[1] Rowan Moore (2019: 48) Jock McFayden London, Royal Academy of Arts.

[2] Ibid: 72. McFayden also talks about the early work of himself and others ‘before art became monetised’ in his Artist’s Preface to this book (ibid: 10).

[3] Cited by Simon Groom (SG) in an interview with the artist in the RA catalogue (2022:44)

[4] Cited Moore op.cit: 41

[5] The artist cited in catalogue interview with SG op.cit.: 30

[6] Ibid: 48