LONDON ART BLOG 3B: Speaking of the ‘Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear’ (1889) Louis van Tilborgh says that, in the book accompanying this exhibition: ‘although our attention is drawn to Van Gogh’s bandaged face, the style is so dominant and so radiant that the depiction of his features seems to recede into the background’. Tilborgh goes on to say that the artist thus achieved his goal that: ‘painting would become “more music and less sculpture”’.[1] Self-portrayal and art focused on the exhibition accompanying Karen Serres (Ed.) Van Gogh: Self-Portraits London, The Courtauld Gallery with Paul Holberton Publishing).

In my photograph above the portrait I refer to in my title has a central position in the second and last room of the Courtauld’s Van Gogh exhibition. But more importantly, even on this minor scale we can see the painting draws your attention to its artistry. Even thus diminished, I would contend that the boldness of its colour contrasts attract and compel our viewing. These contrasts and harmonic play are even further emphasised by the bold coloration of a sample Japanese print beyond and behind, as it were the variegated and harmonising blues of the sitter’s eyes. They have blues in them that even harmonise with the sitter’s coat button.

Colour in this painting, as often in Van Gogh is constantly being reflected between figure, his clothing, objects in the environment and the whole ensemble of the painting’s composition, down to the shading of flesh tones in striking ways. Colours are not only reflected but tonally varied, sometimes as an effect of different kinds of application of that colour (as striated brushstrokes, dabs or layering of hatches or careful precisely captured moments of a fully delivered patch of closely painted colour, using a much smaller brush). A marine blue in the sitter’s scarf mirrors the water in the Japanese, as the deeper blue of the hat is recalled by the clothing. The colouring is not so much composed structurally but as harmonies are in the time of a musical piece. There is a rhythm, as it were, that shapes itself over the flat surface of the canvas as the viewer’s semi-conscious eye saccades comprehend its patterned wholeness. It is the action of the eye in comprehending a whole [picture that gives, I would suggest, one of the temporal dimensions of artistic form.

Although Tilborgh’s essay is one of the finest contemporary assessments of Van Gogh I have read, his grasp of what he believes to Van Gogh’s artistic project is far from clearly defined out of the written evidence, largely because Van Gogh’s statement are buried in private letter and have to both be interpreted in terms of statements from other letters to other people where the links between statements remains unclear. There is no Van Gogh manifesto that will support Tilborgh’s view that Van Gogh had a distinct and articulated conception of what a modern artist like himself ought to aiming for in art. The aspiration of art to the condition of music has meant many things to many artists. Otherwise Van Gogh’s aspirations are expressed in metaphor, such as revival; an awakening of art from the winding-clothes of its dead past forms for instance, as a new spring of youth to old age and as a return to the primitive energies of art such as that of Japan. Tilborgh unites these metaphors without quite translating them for Van Gogh and ties them to the aspiration for the new artist to become ‘a colourist such as there hasn’t been before’.[2] That these ideas also have the colouring of a replacement for religious belief is a point Tilborgh has already made in his essay citing known Van Gogh literary influences, such as the Scottish philosophical historian, Thomas Carlyle, the French philosophical historian, Jules Michelet and Victor Hugo who popularised the latter. These secularist spiritual revivals through art employ aspirations for a vaguely defined (as indeed it needs to be given its nature) and ungraspable ‘infinite’ dimension to life which is designated by the name ‘Poetry’.[3]

For Tilborgh the canvas on which a painter’s art emerges was for van Gogh this patterned surface of colour, modelled for Van Gogh by Japanese prints, such as those of Hiroshige. Hence the concentration, according to Tilborgh, of Van Gogh self-portraits not on the sitter, who is merely there but the whole picture in which they appear metamorphosed, together with their background, into something other, something Van Gogh called either poetry or the effluvia of genius.[4] Tilborgh does not connect this to an early aspiration of Van Gogh that he also mentions, and which preceded the practical decision to become, a portrait artist because portraits sell. But I think it does connect and it suggests that in a portrait the sitter is not an individual whose specific interior life is to be pictured in a way no photograph could do but a type of something less specific and more significant for the whole mass of humanity, something that only the artist, despite the sitter, could create. This is how he saw Rembrandt as a painter ‘magician’: working with ‘imagination, sentiment’ in order not to ‘hold a mirror up things’ but in a way that ‘creates them amazingly, but also poeticizes’.[5]

Why I stress the emergent, rather than fully articulated, version of Van Gogh’s project according to Tilborgh is that critics often simplify the ‘creative’ aspects of portrait-making (and this is true of Tilborgh’s prose too at times – but it is also a contradiction in Van Gogh himself). For instance, Tilborgh argues that given the different purposes portraiture served for an artist like Van Gogh – one being the attempt to make saleable commodities to picture buyers – that the artist may have only emphasised the creative element in painting in order to show he could do ‘greater justice to what the sitter represented, their nature or character’. [6] But that is not the higher order of beauty that elsewhere Van Gogh required that goes beyond the sitter’s subjective self to something generalisable to all life (artist, viewer, humanity, nature and so on). But critics, as I say simplify. From this comes the popular interest in the argument that Van Gogh shows us what it feels to be a mad man himself. It’s a view I have contested in terms of the Saint-Remy landscapes for instance (see the short blog at link if interested).

I very much like the critical work of Adrian Searle but his positive assessment of this exhibition in The Guardian says of Van Gogh’s self-portraiture that he was “trying to do something other than capture brute likeness or appearance, something more like vivid living presence”. In doing so, he continues, the artist achieved “almost monumentality”’.[7] Three things concern me in this version of the populist’s Van Gogh. First, that he is in fact only deepening apprehension of his subject or sitter, rather than creating anew as does poetry in Van Gogh’s assessment. Secondly, that the purposes of his engagement with ‘living presence’ was a merely illustrative (again of his sitter / subject) vividness of colour. Thirdly, that his art monumentalises its subjects, which is to capture them in an attitude that at their death will be their enduring impression on humanity forever. This is all too much the stuff of what Van Gogh saw as dead and dying art serving society rather than changing it, as Romantic artists, after Goethe, required that we do. The term ‘vivid’ is vague and often criticised in the attempts of learners to describe what they see in an art work because it is otherwise difficult to articulate. The word, of course, considering its etymology, ought to apply to a notion of capturing that which is like what we mean by ‘life’, considered as something other than the appearance and stillness as the dead image. In that sense it the word merely replicates Searle’s phrase ‘living presence’ for which it is used as an adjective.

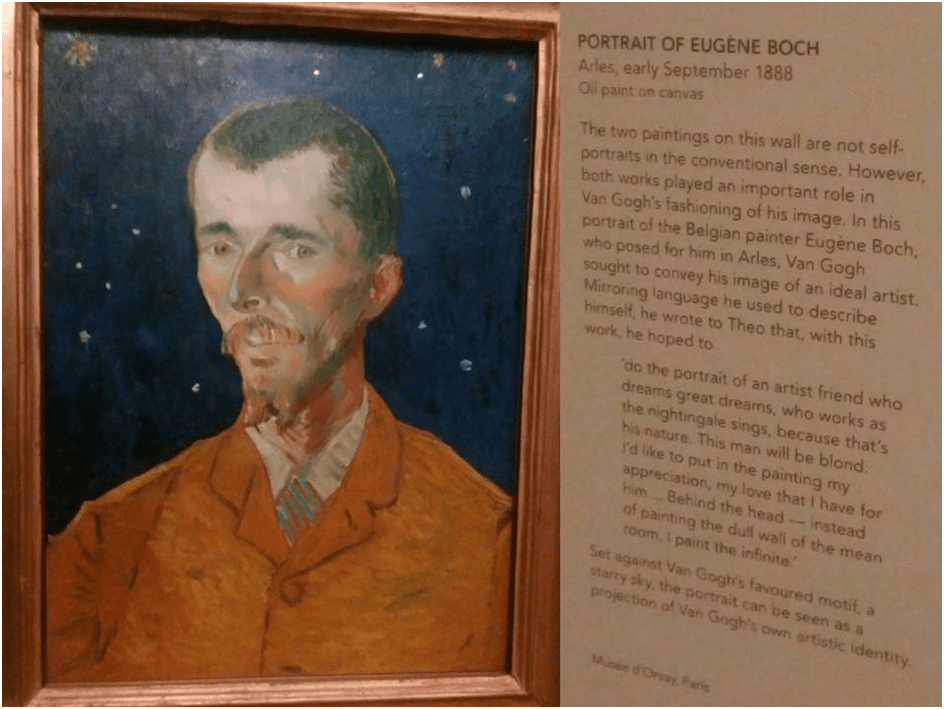

Romanticism required that knowledge of a thing and the worlds that contained it should be much more than a static or dead object of thought. The ‘monumental’ in art, even in its very vaguest use as meaning ‘something very significant’, pertains to a thing that is unchanging and essentially rigid in form, something meant to outlast the ‘living’ of many generations. And Van Gogh is the heir of Romantic philosophers and artists in many media. Hence his art has to live qua art – as the thing it is. This is, in my view, why he sought the appellation ‘colourist’. He need be that which redeems the life otherwise monochrome and containing only forms bounded by lines in its appearance and effect. Surely that is why, if we look for a manifesto of art as painting we look to, as Tilborgh shows us in his essay and the show in its caption (reproduced below), Portrait of Eugène Boch (Sept. 1888).

The point made is that Van Gogh was less interested in the boundaries of self (though it was of interest that Boch looked like him to a degree, or that the personality be apprehended at a deeper level but that the painting creates a whole in which figure and background are part of the same idea – sometimes complementary and sometimes contradictory and contesting but aspiring to the condition of what Romantic artists called music and which they typified (as in the quotation cited in the caption) birdsong. What matters is the rhythmic use of colour and non-monochromatic effects of light and shade to which every other aim of the painting bends, colours which reflect and tonally variegate across the whole with little or no regard to verisimilitude. And the context is that of the ‘infinite’ suggested the ‘richest, most intense blue’: ‘… the brightly lit blond head, against this rich blue background achieves a mysterious effect, like a star in the deep azure’… That ‘star in the deep azure’ is no symbol, let it be noted, of the inner turmoil people insist in seeing in the ‘Starry Night’ when they interpret its life-giving spirals as ‘mad’ but of creativity, and creative redemptive humanity.

It is in this context I could, and anyone who took the journey offered by the exhibition seriously, that Van Gogh’s paintings – however dead and dying he appear as a figure – is not the painting we call a Self-Portrait but rather the painting’s reflexive concern with the living application – by hand, brush or other implement – of colours in concert and musical arrangement. It is why at the focal point of Self-Portrait as Painter (1887-8) is the rich palette of colours it bears and which are embedded in the painting, often surreptitiously and tonally variegated but always rhythmically. It is the reasons for the swirls around the figure. Not repressed turmoil but triumphant creativity that takes the dead flesh of a man and revives it in itself or in context. No photograph could show this – and my poor attempts less so – so I have tried to indicate it only in a collage of paintings where the subject is not the sitter Van Gogh but painterly-creativity. It is paint made to live by its dependence on living body gestures.

Perhaps this is the meaning Van Gogh gave in calling his painting of Van Gogh’s Chair(1888-9) a self-portrait, just as the grander chair occupied sometimes by Gauguin became his portrait (1888). The complexities of colour variation that create the singular primary colour effects weave setting, belongings (both usually close to him such as a pipe) or not so (in a box labelled ‘Vincent’). For me it represented Van Gogh’s reprise of why peasant life was a matter of necessary representation throughout his life, in order that the complexity of the continuing life of simple things (and communal things) is recognised. It is full of morning revival of light moreover, unlike Gauguin’s Chair which still sits in old airless candle-lit traditions.

All the best

Steve

[1] Louis van Tilborgh (2022: 54) ‘Van Gogh’s Self-portraits: Reaching for the infinite’ in Karen Serres (Ed.) Van Gogh: Self-Portraits London, The Courtauld Gallery with Paul Holberton Publishing, 37 -62.

[2] See ibid: 46 for these metaphors and for citation from Van Gogh’s letters (Tilborgh’s italics).

[3] See ibid: 50

[4] ‘men of genius communicate by their effluvia, like the stars.’ Van Gogh cited ibid: 51

[5] Van Gogh in 1885 cited Ibid:40

[6] ibid: 40

[7] Adrian Searle (2022: 9) ‘A show of electrifying intimacy’ in The Guardian Wednesday 2 Feb. 2022, 8f.

One thought on “LONDON ART BLOG 3B: Speaking of the ‘Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear’, Louis van Tilborgh says that: ‘the style is so dominant and so radiant that the depiction of his features seems to recede into the background’. Tilborgh goes on to say that the artist thus achieved his goal that: ‘painting would become “more music and less sculpture”’. Self-portrayal and art focused on the exhibition accompanying Karen Serres (Ed.) ‘Van Gogh: Self-Portraits’. ”