LONDON ART BLOG 3A: Art and me: how the Courtauld Institute and Gallery played a part in the silent development of a half-conscious love of the images and painting that make up a cultural tradition about which I remain ambivalent. This is the first part of a blog based on visiting the Courtauld Gallery on the 8th February 2022, ostensibly to see only the Van Gogh: Self-Portraits exhibition (see LONDON ART BLOG 3B on this).

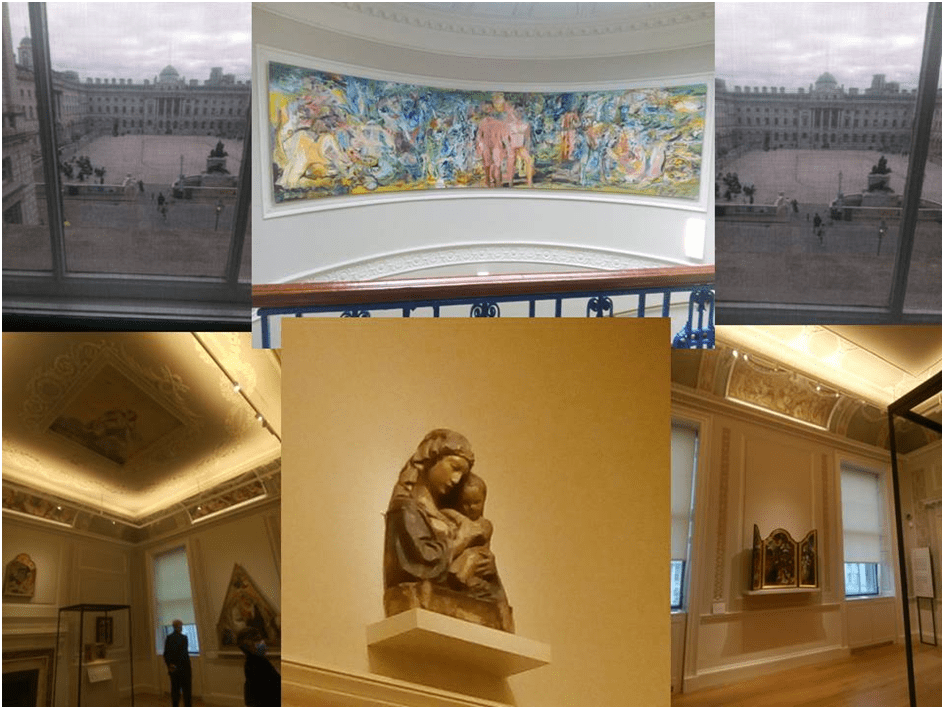

The Courtauld Gallery is now housed in the North wing of Somerset House in rooms and staircases of Baroque splendour. These rooms (and views through the gauzed windows) are those from medieval and Renaissance art section of the collection. The gauze on the windows make the window ‘views’ themselves look like a strange work of art although the purpose of the gauze is to control lighting (and the damage it causes to paint) in the Gallery. The wall-painting on the staircase on the top floor is by Cecily Brown.

The Courtauld Institute of Art and its Gallery were founded in 1932 and its history is told briefly on the page linked here where there is also a list of the holdings in this collection. None of this material then needs to be recounted for the purpose of this blog, which is to commemorate, for myself, the role of that august and monumental double institution (centre of academic art historical teaching ‘excellence’) and Gallery for its permanent collection based on that of Samuel Courtauld, the textile entrepreneur and magnate.

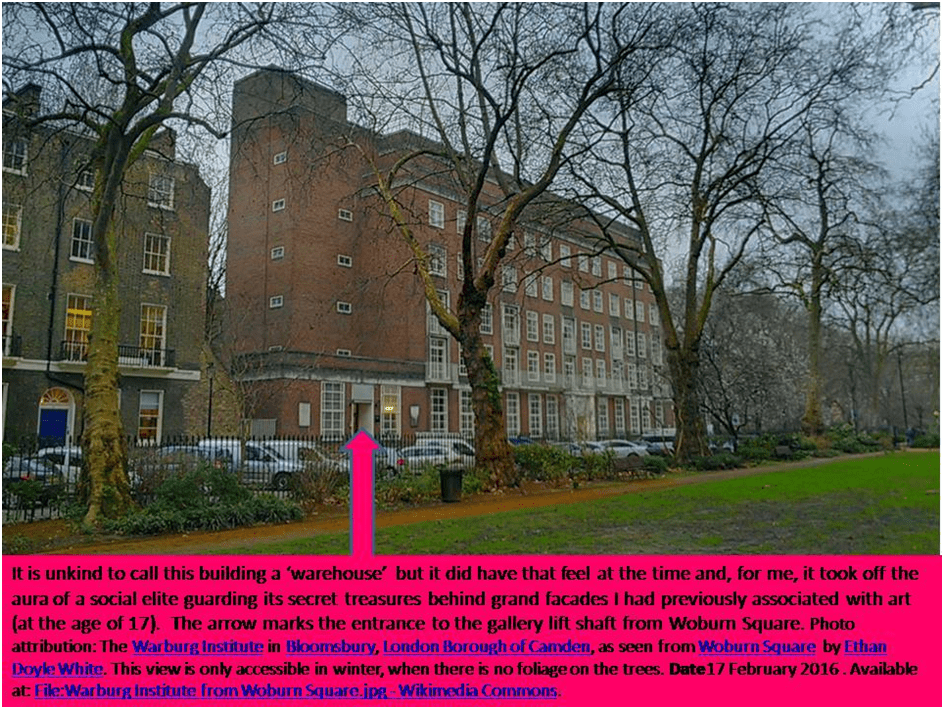

The rich grandeur (in every sense of both words) of the collection I first saw in the equivalent of a posh 50s warehouse, accessed by a creaky service lift used also for the access and egress of huge art works (as part of the Warburg Institute Of Art) seem destined for this place. I was taken there by a friend, Sam Fogg, who was a Courtauld student, and now a published collector of, and authority on, medieval art, Christian and Islamic. Of course it is unfair to call this building a 50s warehouse. Designed and built to high contemporary standards, it became home to the Warburg as part of its (and the Courtauld’s) incorporation in the University of London (which occurred in 1944) in 1957. That incorporation into the university was an intentional honour to Jewish émigré culture, since Warburg and his Institute had fled Nazi Germany. It opened as a Gallery in this building in 1958 and I first saw the collection with Sam in 1975 (I think but memory sometimes fails me).

The Courtauld Gallery collection and its Institute moved (and was for the first time housed together) in 1989 to the North Wing of Somerset House, but I never visited it again till this visit, though, of course I visited London many times: indeed Geoff and I lived in West London and I taught at the Roehampton Institute in the 1980s before and after the move of Courtauld to Somerset House. That is why, I think, I needed to clear up for myself its role in how I perceive my own Bildungsroman of cultural development. Why do I feel something to be so important to me now that I neglected for so long since a first intense acquaintance.

Maybe intensity was in part the problem. Two stories from memory might illustrate this. The first of these relates to the fact that I often looked and compared two nineteenth century paintings: Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère and Renoir’s La Loge (use the links to see the Courtauld licensed images). Ignorant of the ways in which Manet’s reputation was rising in art history and criticism, Sam thought my preference for the Renoir rather quaint and, let’s say, ‘uneducated’ (although there was nothing of disdain in that lovely guy). I ‘read’ these paintings as one might an English novel like George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda, even thinking of how the jewels of the woman reflected the sadness in her eyes – as becomes the fate of Gwendolen Harleth with her brutish aristocratic husband Grandcourt in Eliot’s novel. Although I loved the Manet, the lack of entry into the presenting woman’s ‘character’ made it have a much weaker impact on me, since this was mediated very much by reading external signs for interior emotion, whose absence may be the point of the painting.

At the time, I was not to know that it was precisely this kind of ‘inadequate’ response that academic art history of the time was keen to eradicate as too ‘literary’ on the one hand and too preoccupied with ‘understanding’ figures in the painting as if they were persons. Indeed that last trait was something I had already learned at school that even literary criticism disdained in favour of more formal considerations of the internal structure of a text (or a whole composition in art history terms)[1]. The first hint of my response being such that I needed feel ashamed of such uneducated and uncouth responses to visual art was that my reading of the lady in La Loge was clearly achingly sentimental and self-regarding – and hence very intensely sentimental. I may know now why.

I think it is true to say retrospectively that I, at the time, fully identified with this woman’s alienation from the man behind her, whose eyes were everywhere but on her – a thing a young queer boy who felt he could only love a ‘real’ (and therefore ‘heterosexual’) man. You can see why I might have later cringed at this boy’s way of structuring his feelings around an artwork. Even on this visit, I found I avoided going to stare at either of these paintings, as had been my wont, because (perhaps, since i can’t know this for certain) I am still ashamed of that boy’s vulnerability to his own ‘construction’ (not all by him but also by pertinent socially coded attitudes that were internalised) as a psychosexual being in the 1960s and 1970s North of England – in ‘God’s Own County’ (Yorkshire) in fact.

The second story concerns response to religious painting and I, in some small way, re-experienced some of these feelings on this visit. The collage above is a record of my visit. Spiritual life in that young boy/man (myself remember) really focused on an appreciation of loss and pain, perhaps a reflex of spiritually (and perhaps at base this sense of the spiritual was a compound of more worldly cognition, emotions and sensations) feeling alone in a world without any hope of achieving a state of what I called ‘love’. (You have to remember I came from rural Yorkshire and had not, as I was in Year Two, identified with UCL’s wonderful GaySoc). Was this why I so responded to the very physical and Baroque structure of emotion in Ruben’s ‘Deposition’ piece of 1611, usually titled The Descent from the Cross? For this is spirituality tied to a longing for the physical and nude body of a ‘real’ but lost man.

There are no signs of the redemption I could then see in this painting and I had no way of linking it, as I should have done, to structures of religious feeling sponsored by the counter-Reformation that relished images of pain in ways that some Northern Occidental medieval art had done as an instrument of Churchly control. Some of that pain came back because one is never not connected to one’s earlier vulnerabilities – indeed I see it as necessary for anything like mental health. This time and on this 2022 visit, I revelled in seeing that the formal characteristics of a Botticelli crucifixion piece like The Trinity with Saints Mary Magdalene and John the Baptist like that in the Courtauld and how it could have helped me see the body as something not intrinsically tragic in its affect in a less oppressive society. I must have seen that Botticelli painting, though before its glorious restoration (see link above), but never registered that a ‘spiritual’ (and hopeful) take on naked male beauty was possible in art, although it wasn’t much relished still in my lately taken Open University History of Art course (a very unhappy time).

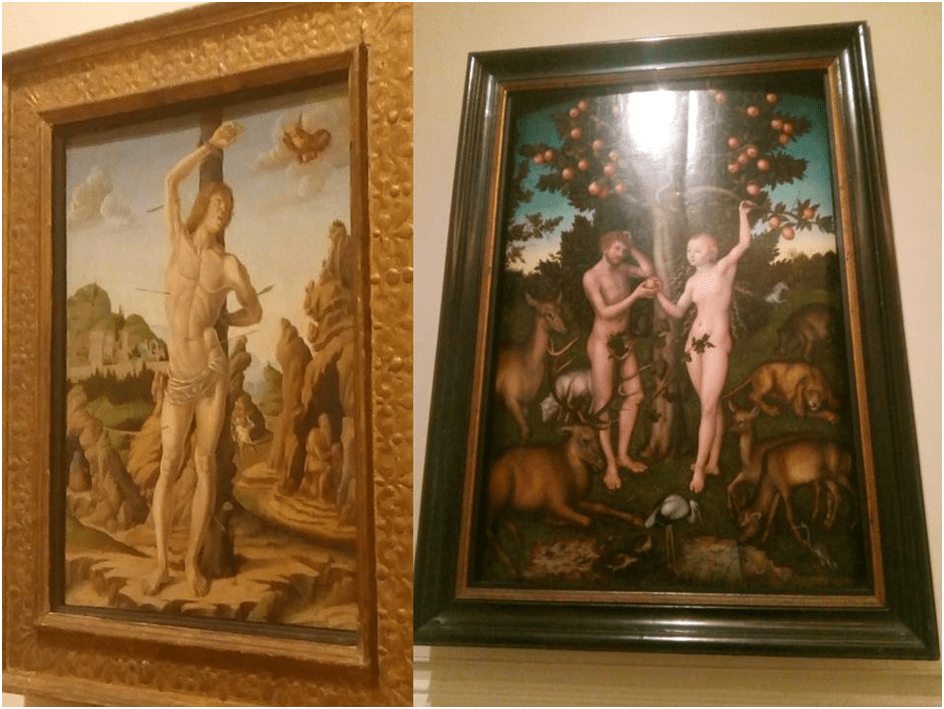

In the current visit I have relished my ability to show a more balanced and certainly more educated response to the meaning and intended affect (and the reason there are unintended ones) of nudity in spiritual art and its links to both ideologies of familial sexuality and, in the case of countless representations of Saint Sebastian up to Derek Jarman, of ‘homoeroticism’ as a layer of conflicting responses in a complex culture. I have to admit, though, that I still flinched at the pain of the Rubens painting seeing it again (remembering how it used to confront you on a facing wall on entry in the old Gallery in Woburn Square). But this flinch may be now because of my distance from Baroque sensibilities so like that of a yet immature queer man born in the 1950s like myself, rather than entirely from a remembered vulnerability.

On this visit I found myself wanting to discourse on the iconography of male nudity and how it differs in paintings separated by theme, intention and time (I am such a bore – LOL). Thus, I just looked at Marc Zoppo’s late fifteenth century Saint Sebastian, pictured with other ‘kinds’ of holy men like Saint Jerome, and felt that the signs were available here for me now both culturally and emotionally, to think and feel more freely (at 67 it’s taken some time you might think). In this picture spiritual aestheticism, asceticism and the frankly visually sexual come into conflict. And don’t get me started on Cranach’s Adam and Eve, which I used to pass over in the old Gallery, but this time in the Courtauld welcomed like an old friend when seeing him, as the painting is seen on entering the appropriate suite of rooms at the end of a long vista of open doors. The painting drew me on.

In the above account I have tried to be honest (perhaps embarrassingly so) about how response to art was structured in a working class (and semi-dyspraxia when holding art implements) boy (17 or 18) educated to all I knew of art through English novels (rather than, say those of Zola) and with no education in art or its history. These played no part in a serious Northern state Grammar School education for me. And maybe, we need to see our development for what it is. I have found no disadvantage in coming to visual art late. I even rejoice in my own eclectic and much personalised interests: I get bored by a lot of very conventional art history as my opinionated blogs show. This latter fact is no problem now for culturally we have the wondrous Mary Beard and Simon Schama, for example, to show us the way to multi-disciplinary approaches to art.

I think this autobiographical turn of thought was stimulated by a walk from Kings Cross Station, where i always arrived back in London, past Cartwright Gardens where once stood the all-male London University Commonwealth Hall, taking learners from ever college from Barts’ Medical school to the Courtauld institute as well as University College where I studied. Thence, in Marchmont Street, I called in on to Gay’s the Word bookshop, before walking alongside Russell Square to the Kingsway. This journey was replete with memorials for me, even though I used my free pensioner’s bus pass for part of the journey on Kingsway to re-orientate to my older body.

Once there I allowed my current tastes and eclectic interests (reflected in my other blogs) to dictate those pictures I would see, such as the tremendous examples held by them of Cezanne, who is now a painter I revere, although not so now Renoir or even (that much yet) Manet. The examples at the Courtauld cover some part of the great range of Cezanne – in figural art, still life and luscious variegated landscapes, as seen below.

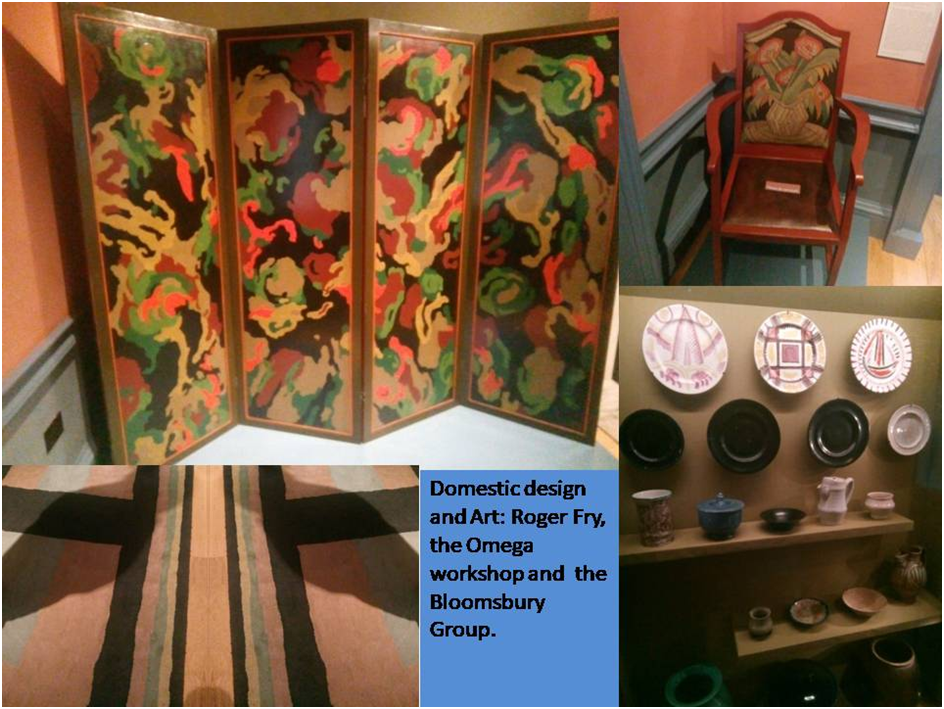

It was an indulgence to see the Bloomsbury room and not, for a moment at least, to think mainly of Virginia Woolf but the sister of hers i have learned to respect and her partner, the queer artist Duncan grant. Bloomsbury after all was queer in its structure from top to bottom and yet helped restructure the relations between things others insisted were binaries which they are not, such as male-female, heterosexual – homosexual and in doing so felt the ability to restructure domestic environments through design as well as art. I saw here a beautifully restored Duncan grant screen. It makes up (a little) for never having visited Charleston.

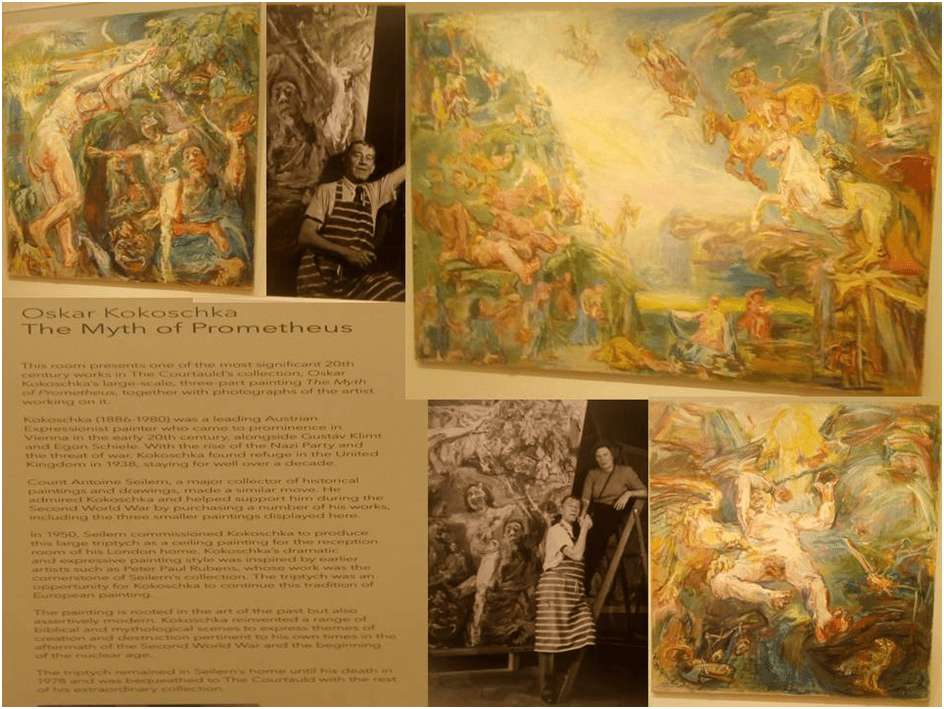

But maybe my favoured experience was to see the magnificent mythic Prometheus triptych by Oscar Kokoschka. Here was a painter introduced to me by the same Sam Fogg I mentioned earlier for in the 1970s German Expressionism was not the dirty word it was to become in the rush away from the ‘literary’ in visual art and the non-formal levels of meaning. I can’t yet write about him but to see him was a treat, fulfilling much reading about him and his circle that I continue to do.

This is a ragged blog. I apologise if you read it and found it too self-regarding and of, therefore, no interest to others. All I can say, is I needed to write it because my intention had been to concentrate entirely on the Van Gogh exhibition and I couldn’t do that till i had written these reflections ‘out of’ me. To that latter I turn in LONDON ART BLOG 3B. Hope you join me.

All the Best

Steve

[1] From L.C. Knights (1933) ‘How Many Children Had Lady Macbeth’.

One thought on “LONDON ART BLOG 3A: Art and me. This is the first part of a blog based on visiting the Courtauld Gallery on the 8th February 2022, ostensibly to see only the Van Gogh: Self-Portraits exhibition (see LONDON ART BLOG 3B on this). ”