LONDON ART BLOG 2: In her brief summary contribution to the 2021 book accompanying the Royal Academy’s delayed exhibition Francis Bacon: Man and Beast, Catherine Lampert says, as if in summary of Bacon’s attitude to the artistic image: ‘Watch me go into a territory that others do not dare represent’.[1] This blog is about the meaning, effects and affects of the imagery of dualistic terror, agony and pain considered in the Royal Academy exhibition Francis Bacon: Man and Beast based on a visit to it on the 8th February 2022 and the very good catalogue (Peter Sawbridge (Ed. Director) et.al. Francis Bacon: Man and Beast London, Royal Academy of Arts) with a lead essay by Michael Peppiatt.

This is the second of five blogs marking my experience of art confronted on a trip alone to London in February 8th– 9th 2022. London was sunny and warm but in two days it was tiring to see four exhibitions. Nevertheless, they were of such importance to me that see them I must. This order of seeing was the exhibitions of Van Gogh and the Courtauld collection, Francis Bacon at the RA, Jock McFayden at the same, Dürer at the National Gallery and finally Louise Bourgeois at the Hayward Gallery. The order of writing was determined on the basis of which exhibitions of which I had completed enough reading – although that reading was really just the book accompanying the exhibition.

This particular blog looks at the Royal Academy’s exhibition of Francis Bacon. It begins with thoughts produced well before seeing the exhibition based on questions raised by the accompanying book and with a very shallow question. Maybe the question hardly bears the dignity of scrutiny – but there you go. As I read the book it seemed to me that it was still possible to ask how much of Francis Bacon’s courtship with ‘the terrible’ and ‘bestial’ was a matter of mere theatrical performance? And in the light of Lampert’s summary, cited in my title, of what might have been his attitude to the search for definitive imagery for his aesthetic, we could posit a certain amount of exhibitionism in his penchant for showing pain and nervous terror so unswervingly and without much nuance.

Moreover Bacon’s constant references to seeing the animal in the human and vice-versa at the instinctual level needs also to be put into the context of his friend, Desmond Morris’ revelation in the book accompanying the exhibition of an incident where it was not possible for Morris to tell Bacon that the artist had failed to distinguish a baboon’s yawn from an authentic cry of animal pain, lest he disturb the painter’s amour propre.[2] It may then be that, when we view these paintings, we are not receiving much authoritative knowledge of the mammalian nervous system, so often appealed to by Bacon, as the more literary sources of his imagery and the aim of its effects and affects. It may be too that Bacon here as well concentrated on visual affect without knowledge of the meanings of the phenomena he thought he was representing. But I doubt that such a view of his work would get us far. Moreover, it would seem to me that the line between theatricality of performance and the performances of everyday life that constitute its experience is much more porous than we might think in so many phenomena of living – as either animal, human or both, as studies of the theory of mind in both domains constantly remind us.

Bacon’s preoccupation with torture cannot be seen as purely theatrical because it was enacted since enactment of intention is indistinguishable whatever the mix of motives it can be resolved into. It is a fundamental characteristic, for instance, of psychiatric ‘symptoms’, sometimes known as ‘acting out’. We should beware statements about the causes of his interests in animal life that become overly and overtly simplistic. Of these simplistic summations, the literature on Bacon is already full, especially when it is least thoughtful: as in Peppiatt’s sometimes crass references to the effects of Bacon observing from afar Nazi methodologies of government. Even more when Peppiatt refers them to the nature, as possibly only Bacon saw it and therefore not its essence at all, of the sadomasochistic ’queer scene’ of the 1940s. I find these pages of his essay in the catalogue more than crass in fact.[3] So, although I read all of this before visiting the exhibition, I was determined to try and see Bacon’s imagery as clean of such preconceptions as possible. Hence these few opening paragraphs, here and above, were typed at least three weeks before I visited the exhibition proper.

My visit proper was on the 8th February 2022. It was spoiled perhaps by having spent so long when visiting the Van Gogh exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery, spending even more time renewing my acquaintance with that Gallery’s stupendous and rich permanent collection. A walk along the Strand, through Trafalgar Square to the Piccadilly entrance of the Royal Academy left my energy resources depleted and my camera very near having lost all charge for taking photographs. Perhaps I wasted some of that energy by recording landmarks along the journey rather than saving them FOR the exhibition.

Hence the ones I did take did not represent choice as much as desperation to, at least, have some record of this gathering of paintings that I have never seen before largely, ‘in the flesh’ (as art historians so weirdly say). In this piece I have tried then to find other sources of pictures I saw after long longing to do so, such as The Two Figures, which Lucian Freud knew as ‘The Buggers’.

Of course, seeing this ‘in the flesh’ is a revelation not least because of the way that the painting itself both suggests the fleshly and, at the same time abstracts it, into the context and materials of art. After all, the subject surely is a recreation (in both senses of the word since play is important here) of the classical image (from Pergamum) of The Wrestlers of which the Royal Academy itself has a copy even if it also a recall of a Muybridge photograph.[4] And although the image is rendered more ambiguous so that it might represent an act of anal intercourse, strangely (given descriptions of it previously encountered), this is nowhere near as violent an image as I had expected. It is not a depiction of rape or a non-consensual act nor a record of the violent sex between Bacon and some of his lovers, notably Peter Lacy. What disturbs, if anything, is the blurred eyes of the supine figure seem, if one could properly detect them, to be looking out from the work at the viewer. The figure on top seems too to have a foot suspended out of the bed, without any surface beneath it from which it might gain propulsion in the act of copulation, if that is what the act is. Catherine Howe is determined to see the representation of anal sex here and elsewhere as ‘loaded with the frisson of transgression, reinforcing psychiatric associations of paranoia and same-sex desire, as well as the persecutory atmosphere of the 1950s’.[5]

What also deliberately confuses is that bed appears to be a floating cushion of surface paint – held in or semi-constrained only by a framework to its rear out of which it seems to be propelled. The framework moreover refuses to accommodate the bed head and foot as they would be seen by a viewer of this scene, and they too break the constraint of any framework. If the perspective of a room scene is suggested it is also transgressed by such markings. The paintwork often merely indicates the surface of the picture frame, such that the streaks down from above and the apparent curving ‘projectiles’ from below seem part of a blurring effect of the white paint out of which both figures and bed are fashioned.

Bacon was a difficult man to like. In the most brilliant essay in the book accompanying the exhibition, Stephen F. Eisenman emphasises that though some of the return to the fauna of ‘nature’ or bestiality of Bacon mirrors an ‘iconographical tradition’ he names “the cry of nature”. However in Bacon’s hands, the theme does not indicate a radical rejection of the abuse by humans of nature and animals as it is in its origins in the philosopher Rousseau, the Jacobin Scot John Oswald, William Blake and Chaïm Soutine. Indeed Eisenman says specifically that ‘Bacon was no Rousseau, Oswald, Blake or Soutine’ and that ‘Bacon sometimes revelled in callousness towards both animals and humans’.[6]

I find it almost impossible though to believe in this callous (callous to the point of inhumanity) character, although I think I fully accept that the chief architect of that construct was Bacon himself. The key word in Eisenman’s assessment is not ‘callous’ but ’revelled’. The Bacon I believe in is a man who played roles continually and who sometimes was unable to distinguish (or did not desire to distinguish) between what was play and what was urgent and real. Though Eisenman cites Bacon’s view, as expressed to Nikos Stangos that there was ‘no reason’ why scientists should not ‘experiment on babies rather than animals’ one is reminded of Jonathan Swift’s Modest Proposal, wherein satire’s playfulness retains the cruelty of that being satirised.[7] At the root of this is a radical belief I think in the uselessness of human speech and action and a deep sense that the world is inexplicable in rational terms or language that pretends to deal in such terms. Peppiatt says the images of his remains ‘locked in their own unknowability’.[8] Colm Tóibín says more fully that those images, of animality in particular, are ‘visually arresting and not clear in their meaning, but fully strange, astonishing the nervous system before there is time for the intelligence to resist their impact’.[9]

If these writers are correct, then Bacon’s art is bound to appear to queer everything that makes life comprehensible or even meaningful, acting out his vision rather than articulating it in ways that can be fully shared discursively or co-operatively acted upon. The political and social hopelessness of this scares me still in Bacon’s work (and in this sense he is perhaps again like Jonathan Swift). This points to why I think it is difficult to see so many examples of Bacon’s work in one place –in an exhibition such as this for instance. When we look at these images our perplexity and disturbance is, as Bacon intended, felt almost viscerally rather than thought or felt in a way that suits the inevitable communal nature of a public exhibition. Conversations I overheard in the exhibition hall – the successful and meaningful ones – were those that concentrated on Bacon’s highly finished textured surfaces. These conversations stayed at the matter of painterly technique. Conversations about ideas or communicable emotions were absent, at least in my hearing. The works perform something on the nervous system of course but how never was articulated in my hearing.

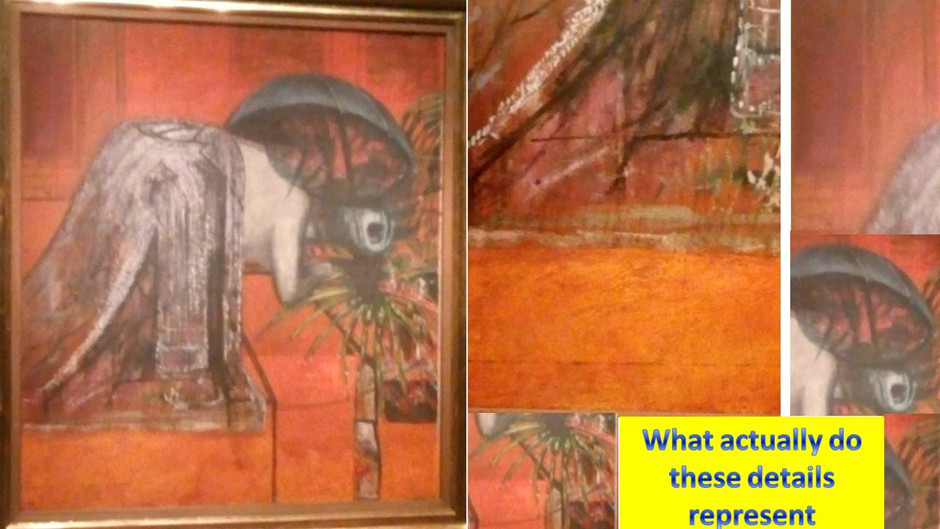

I tried to understand why when i looked at this early work which i have known for a long time since it is held by Huddersfield Art Gallery and was available to me in my youth. Known as Figure Study II (1945-46) I feel each time I see it as fascinated and held as i feel inarticulate before it. I have created to collage to try and understand why:

I choose fragments of the painting in my collage to enact the ways in which any viewer interrogates detail that seem intelligible but on closer examination are not, such as the palm tree figure or umbrella. What may be clothing on the lower half of a bent figure may be also only a kind of patterned cover. Once investigated in detail, even the patterning is absent and resolves into fragments of brush strokes, painting dabs, uneven and webbed hatching, dark voids and broken brushstrokes. The representational and mimetic functions of the media are suggested but never completed into something knowable.

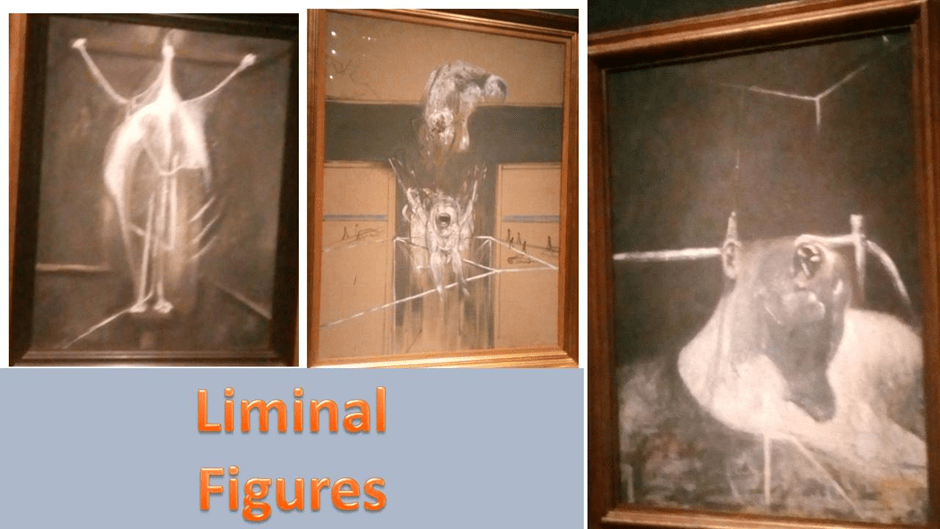

This has sometimes caused commentators to define the figurative in bacon not just as on a cusp between animal and human but as something embodied only as an appearance – as ghost, spirit or ‘ectoplasm’. Thus even the very early pieces of Bacon’s work are in a kind of transitional status between the embodied and the insubstantial or emergent in form as well as animal and human. It is this aspect of Bacon’s work that makes me feel that a focus on the animal in Bacon is as reductive as any other explanatory paradigm. It raises too many hard-to-support translations of the art rather than creating understanding of the wider visceral effects of the imagery.

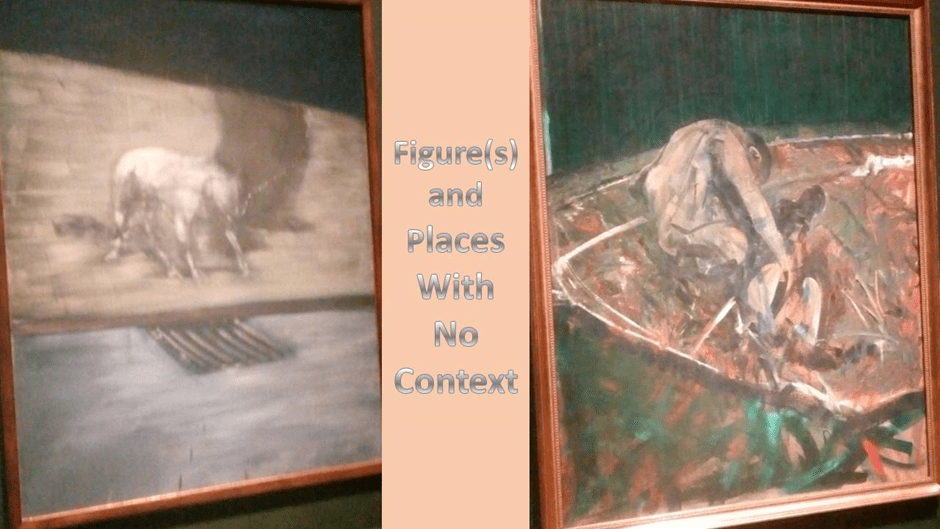

Art historical discourse when it is not about purely formal and compositional matters requires some way of discussing content in terms of the figures and places (even if these are idealised) but such knowledge is cut short by Bacon’s images where neither figures nor places have clear context – something often given away by vague titles that refuse specification.

Thus above in Man and Dog (1953) the man is a de-contextualised shadow of the putative dog and the space has no clear definition, depth or point of view. Indeed the spaces within the painting are neither marked as ground or background. The 1956-57 Figures in a Landscape again does not distinguish putative shadow from putative substance or the relative depths of ground on which the figure stands. Even Bacon’s ubiquitous frameworks, in the screaming Pope pictures for instance are merely cognitive structures without context or clear interpretation (as being representations of a room, for instance, might make them).

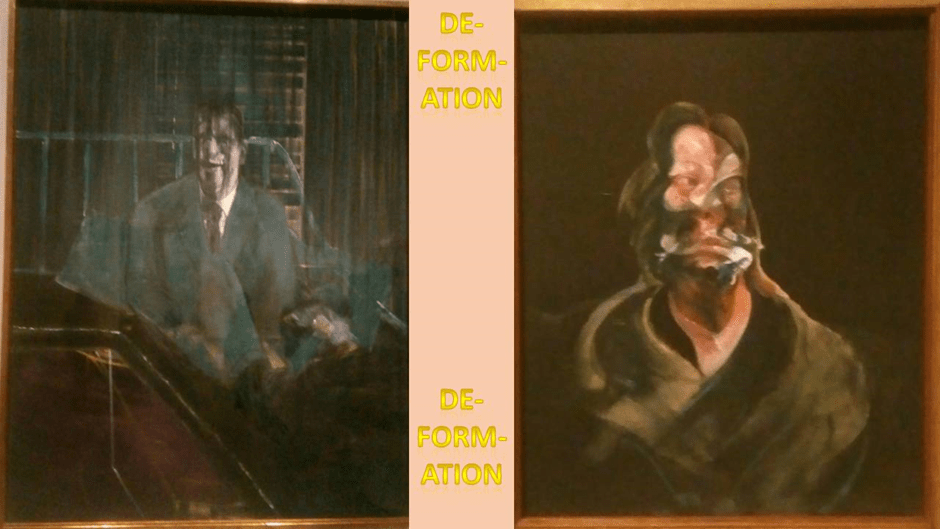

Bacon’s portraits purport – as above – to be figures we might recognise, although mainly people only known in Bacon’s close circle, they are also as easily describable as mere marionettes. They are anyway locked behind, to the point where it blurs vision and takes away pretence of a likeness to animal, human or ghost, by striations of surface paint.[10] The deformations of the face of Isabel Rawsthorne above too in the 1966 portrait cannot be explained as a perspectival experiment as in cubism. We have to be open to a flesh that is refusing formation or definition.

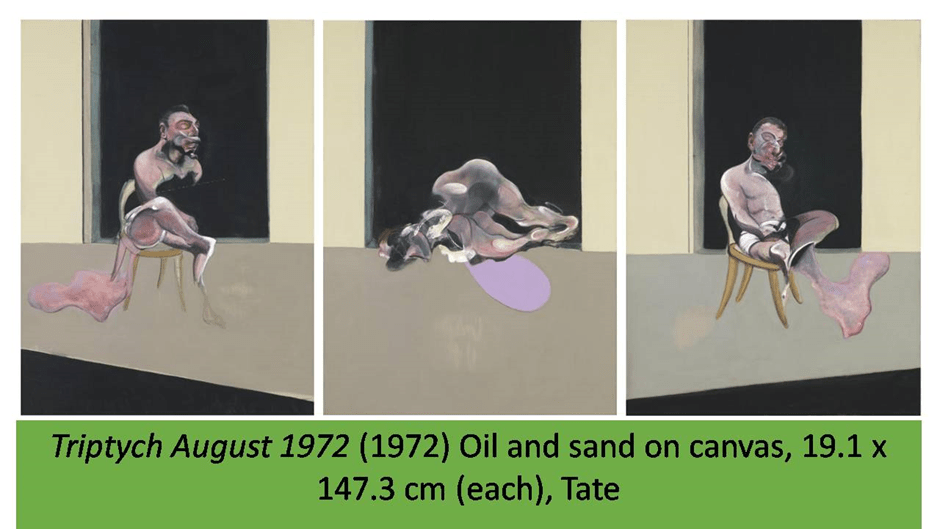

Of course the triumph of such an exhibition as this is, whatever it claims for itself, the chance to see the magnificent triptychs assembled in full on the huge and generous walls of the Royal Academy. I sometimes want to cry at the representations of George Dyer, such as the Triptych, August 1972. Yet that I do may be because we now know the terrible story of Dyer’s death. This including the fact that Bacon was complicit in covering up that death long enough to make his art centre stage at his simultaneous Paris exhibition. However, my pain is also because the central picture of the triptych is a reprise of the Two Figures painting I discussed above and which predated Dyer’s time with Bacon.

When we see this we see how the deformation of the figures here – either by slow fluid disintegration or by their emergence from chaotic and plastic materials – is about the failure of our sensations in states we call love or hate, for instance, to ever be clear or uncomplicated from our visceral appetite and fears.

Whether this blog is meaningful I do not know. It is how I felt at the time.

But see this exhibition. These paintings will not be reassembled on this scale now for many years in the future.

All the best

Steve

Other of my blogs on Bacon:

[1]Catherine Lampert (2021: 150) in Peter Sawbridge (Ed. Director) et.al. Francis Bacon: Man and Beast London, Royal Academy of Arts. See page 150 only for her contribution.

[2] Desmond Morris (2021: 141) in ibid. See page 141 only for his contribution.

[3] Michael Peppiatt (2021: 18-20) ‘Francis Bacon: Man and Beast’ in ibid: 12 – 35.

[4] Michael Peppiatt (2021:21) ‘Francis Bacon: Man and Beast’ in ibid: 12 – 37.

[5] Catherine Howe (2021: 57) ‘Man, Woman, Beast: bacon’s Nudes’ in ibid: 56 – 65.

[6] Stephen F. Eisenman (2021: 53) ‘The Animal That Is Not One’ in ibid: 38 – 55

[7] Ibid: 53

[8] Peppiatt op.cit.: 14

[9] Colm Tóibín (2021) ‘Appetite and decay: the animal instincts in Bacon’s paintings’ Available at: Appetite and decay: the animal instincts in Bacon’s paintings | Blog | Royal Academy of Arts

[10] Catalogue in Ibid: 93 on Study for a Portrait (1953)

One thought on “LONDON ART BLOG 2: Catherine Lampert says, as if in summary of Bacon’s attitude to the artistic image: ‘Watch me go into a territory that others do not dare represent’. This blog is about the meaning, effects and affects of the imagery of dualistic terror, agony and pain considered in the Royal Academy exhibition ‘Francis Bacon: Man and Beast’ based on a visit to it on the 8th February 2022.”