LONDON ART BLOG 1: Susan Foister & Peter Van Brink say of the exhibition at the National Gallery, Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist in the publication that covers that exhibition: ‘Many new discoveries have been made in the preparation of this exhibition and the accompanying publication’.[1] It is a small claim and Kathryn Murphy reviewing the same for the fine art magazine Apollo says the: ‘exhibition with its rather perfunctory captions, would have benefitted from … glimpses of a stranger, more curious Dürer, restless, wandering, moving at speed’.[2] Reflecting on the possible pitfalls of art exhibitions in the great international art institutions based on single great ‘old masters’ and curated through mainly through academic approaches? How do we know in what way those approaches have worked and how they have not using the exhibition at the National Gallery, Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist based on a visit to it on the 9th February 2022 and the catalogue (Susan Foister & Peter Van Brink (Eds.) Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist London, National Gallery Co. (dist. by Yale University Press).

This is the first of five blogs marking my experience of art confronted on a trip alone to London in February 8th– 9th 2022. London was sunny and warm but in two days it was tiring to see four exhibitions. Nevertheless, they were of such importance to me that see them I must. This order of seeing was the exhibitions of Van Gogh and the Courtauld collection, Francis Bacon at the RA, Jock McFayden at the same, Dürer at the National Gallery and finally Louise Bourgeois at the Hayward Gallery. I walked over Hungerford Bridge and took the following photographs to commemorate my two days before taking the tube to Kings Cross and thence home. The order of writing was determined on the basis of which exhibitions of which I had completed enough reading – although that reading was really just the book accompanying the exhibition.

The first paragraph proper of this blog I had written two weeks before my visit to the Gallery, having read most of the ‘accompanying book’ and a few reviews. Both experiences raised concerns that this was not an exhibition aimed at me, or indeed the vast majority of ‘non-specialist’, as they call us, viewers of art. I want to keep an open mind but if the review of Kathryn Murphy that little in the exhibition matches the promise of one essay in the book, and only that one essay.

The essay is by Joseph Leo Koerner and is entitled ‘Dürer in Motion’.[3] It is indeed a marvellous achievement but whether it requires discussion will depend on its reflection by the exhibition because I noted that this is not an essay singled out in the book’s introduction, nor covered by the things that piece calls praiseworthy. Much of the rest of the book pushes an argument from the academic world about the sufficiency of art history as a discipline, and its key concepts, methodologies and goals as imagined within it and outside it by other disciplines. Some participants support these goals in their most reduced forms fully – especially those essays dealing with mutual influence between Renaissance artists – others find them wanting in appreciation of the economics of art production, sale and distribution in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century and the rationale of travelling (including for commercial reasons). Neither of these topics make for the kind of exhibition that interests me, whilst Koerner’s exciting ideas, as Murphy describes them and i read them in the book do, without any failing in academic rigour – in my view at least.

And what feels like a hint in Murphy that the exhibition lacks something important as an experience of what visual art has, at its finest, to offer is smothered as thick as a Yorkshire man’s butty (as a Yorkshire man I think I can say that) in Jonathan Jones review in The Guardian.

For all its apparent seriousness this exhibition fails to take you to the heart of Dürer. It even made me doubt my adoration of his art. The old-fashioned fustiness – some of the rooms are painted brown and brick as if to make you feel you are in a dusty library – can’t hide a lack of clear argument.

….

For all its ostentatious scholarly air this exhibition misses the point of Dürer’s journeys to Venice completely. It was this: as well as being thrilled by the freedom and sensuality of Venice, what struck Dürer in Italy was a new idea of the artist.[4]

I am no great fan of Jones as a critic, especially when he deals with the town near which I live. However there are warning signs in the ‘apparent seriousness’ and ‘ostentatious scholarly air’ that usually mark my own distrust of the traditions of thin academic traditions and the hubris of great institutions of art and academia, where they lack any interest in the living. So I wait seeing the exhibition with some trepidation. Though see it, I will – just pleased that in the same two days of my visit I see exhibitions on Van Gogh, Francis bacon and Louise Bourgeois (enough to defeat any ‘old-fashioned fustiness’, which sounds like a resurrected version of Carlyle’s Dry-as-Dust stereotypical historical and biographical scholars. I wait for my February visit with interest.

In fact I saw this exhibition this morning (11 a.m. 9th February) armed with rancour from the reviews I cite above and could not agree with either reviewer. Indeed, were that my topic, I would like to reflect on why art reviews in particular seem focused so much on distinguishing the critic’s point of view in such a way that their aim is necessarily antagonistic to the pleasures available from what is to be seen in the exhibition itself. Even if we examine only Jones’ characterisation of the ‘ostentatious scholarly air’ of the exhibition in his eyes, it is difficult to find such ostentation in the exhibition itself or to know in what, in an exhibition as necessarily professional as this, such an air would consist of.

There was much in the exhibition in which I was less interested than might be ideal but that is, in my view, mainly my own limitation. There is much to be learnt from an artist’s notebook and his preliminary drawings, particularly given the detail we associate with early artists of the Northern Renaissance, than I myself find time for. For that reason I willingly admit I missed much that would have been productive of learning for me in the exhibition – whole rooms of drawings for instance I did not examine with anything like the time needed for comprehension let alone to learning further there from. And maybe Katharine Murphy’s Apollo review is fair in the long run, which Jonathan Jones is not. But the problem with both reviews is that they conclude too much about the exhibition itself from the accompanying book, which is, frankly, as disappointing a production as the conventions of academic art history, drained of relevance to the rest of us, can provide. For it is wrong to say as Murphy does that the materials for the analysis in Koerner’s wonderful essay in this book, which she rightly praises, are that difficult to find. I saw lots of ‘glimpses of a stranger, more curious Dürer, restless, wandering, moving at speed’ in this exhibition.[5]

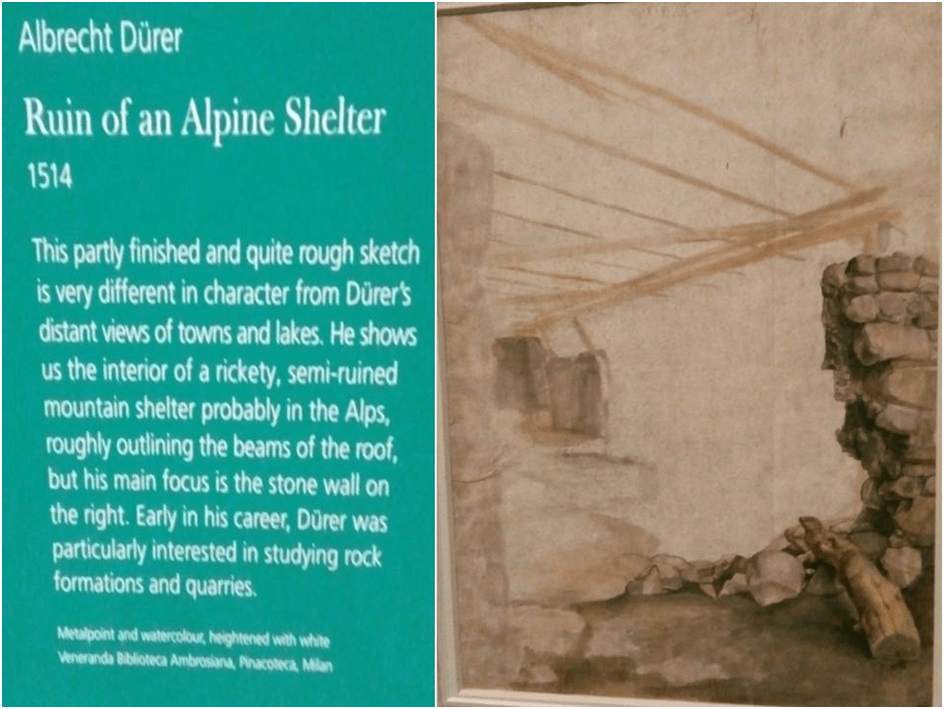

This queer Dürer is ever-present whenever a viewer selects from an exhibition as beautifully presented as this but seeing him owes much more to the viewer’s willingness to perform acts of interpretation. Let’s take, for instance, an example of what might well look like to Murphy and Jones mere ‘original scholarly arguments about the’ context of a specific work (you hear the bored yawn behind that phrase even in Murphy) that really engaged me, an early (1514) unfinished study of the ‘Ruins of an Alpine Shelter’.

I do not know if Murphy considers the caption here reproduced to be one of those she describes, as if of all, as ‘perfunctory’, but it is difficult to know what more one could expect of a caption. For instance it tells us that Dürer only in his early career showed interest in rock shaped by human beings. It also shows us that, for whatever reason, having delineated a ruined wall in great detail Dürer moved on in his journeying rather than complete the features indicated by the rough outlines of the rest of this human shelter or temporary habitation. To me that gave enough to work on because it placed acts of drawing within the motion of a journey as if Dürer were part collecting material and skills for potential later use or not and that he was ready to abandon what became of no interest to him beyond as a show of skill. And the interest in a ruined wall in a ruined habitation is itself a sign that for Dürer, motion is an aspect of time not of speed – for if you wait long enough everything moves.

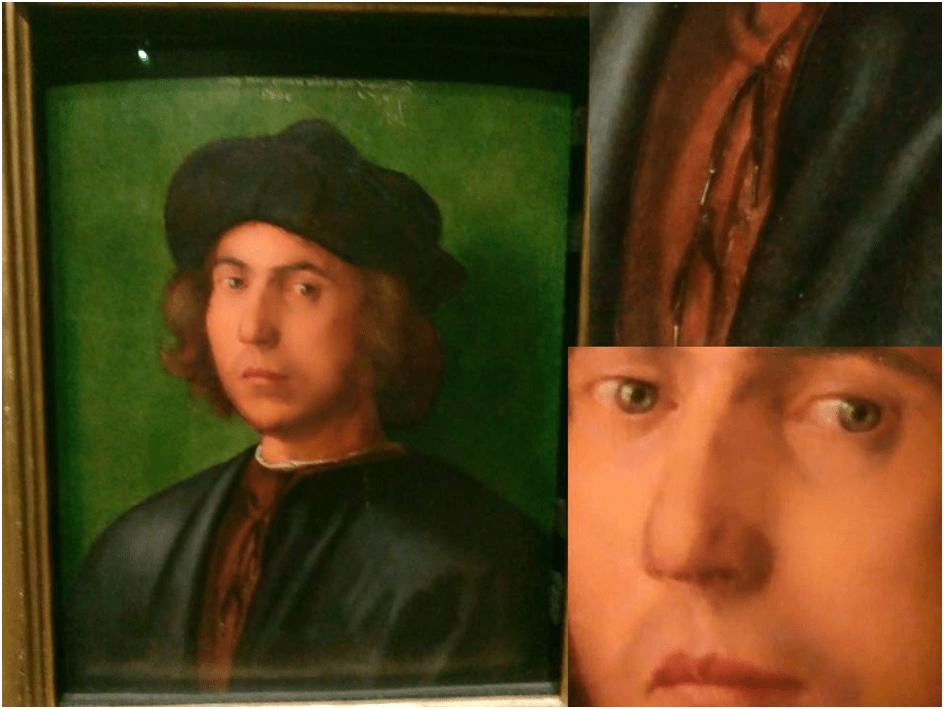

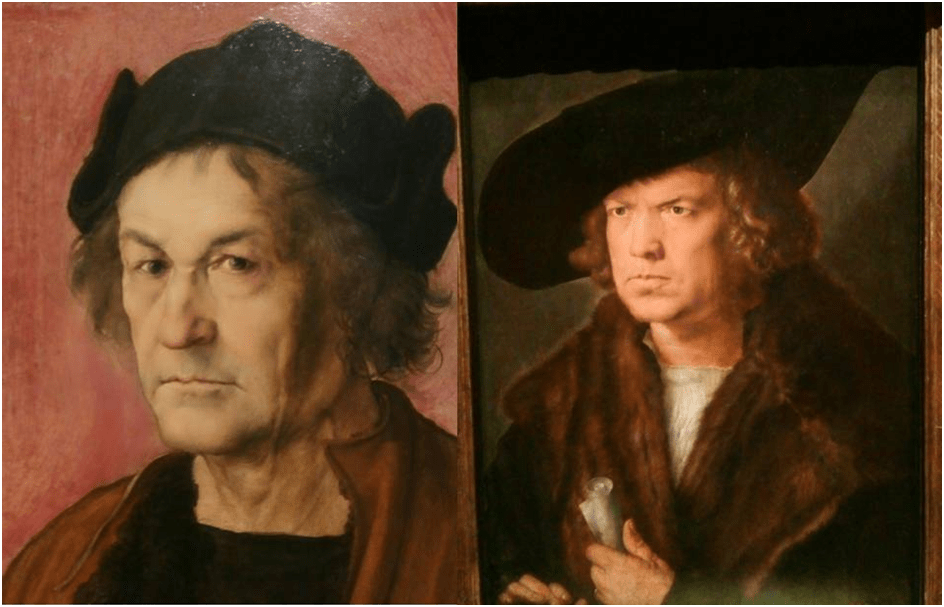

For me this takes me even beyond Koerner’s marvellous essay in the book of the exhibition, which links the artist’s interest in motion to the values of a new mercantile world more evident in the Northern Renaissance than the South, where even merchants, like the Medici, aped the aristocracy. This exhibition is, in some sense, fixed on the idea that Dürer’s travels were as much to do with his status as an entrepreneur – manufacturer and trader of prints of course but also aware where exchange rates for jewels might bring in profits.[6] It links too to a man who, though a sincere Catholic was fascinated by the career of Luther and his challenge to a Papacy Northerners knew to be corrupt, though Jergen Stumpel in the exhibition book doubts his authorship of the words lamenting Luther’s fate in his Journal.[7] It is a world in which the value of men, or women – though that was a different question for him, was not based on birth or status necessarily. In my view, makes his portraits a kind of democratic study of the contradictions between the essential person within them and the appurtenances of status, such as rich clothing, jewellery or novel gadgets. In his 1506 Portrait of a Young Man Dürer captures an almost wet eyed immaturity in his subject with its early shadow of delayed shaving to contrast with his obvious pride in his up-to-date apparel, especially the laces tying his top over which Dürer has clearly spent much care and time on this exquisite detail of a passing fashion.

That is what I, at least, also concluded (without, of course, as art history would chastise me, ‘a shred of hard evidence’) by looking comparatively at an early portrait of the artist’s beloved father (a goldsmith and therefore relatively lowly even as an artist in the world Dürer was to assume after his visit to Italy) and the many fabulously rich merchants and political administrators he served. Those latter were themselves at the service of aristocrats in which the power to consume to excess lay but they were able to counterfeit such status.

The Portrait of a Man (now in the Prado shown above) is a case in point. Till-Holger Borchert speculates that this may be the rich chief tax collector for the duchy of Brabant, Lorenz Sterck. The same writer thinks the rich clothes, especially the dark ostentations headwear, complement his embodied gesture of ‘wilful character and energetic gaze’.[8] To me however the effect is of a clash between clothing and flesh. It shows I’d say that this man undressed and not carrying symbols of his role, such as the scroll in his hand, though he would still be an impressive figure, is still only flesh bearing the marks of age – such as in the silvering hair and scarred lip. These details clash with the finesses of fur and silk he bears over his body. Standard medieval idea though this be, it has also a kind of communalism behind it that seems to be to be Dürer’s. If we look to the portrait of his father there is no richness of dress or coiffure but much of character and a kind of love mixed with the pride in his eyes.

The contrast is to me what makes Dürer a great artist. Of course I am aware of the danger of thinking that we, in the twenty-first century, really comprehend Dürer’s world view, in the same way he understand it and his role within it. As early as 1985 John Berger warned of ‘complacent assumptions of continuity between his time and ours’.[9] Yet surely we need to re-imagine his imagery in our own terms even if we abandon those terms on later more dispassionate study. A case in point concerns two early paintings in this exhibition which tantalised me. The first concerns, as far as I could see, attitudes to motion and travel and is called Lot and His Daughters and was painted on the back of an otherwise unremarkable Madonna and Child (the Child is interesting but not the Madonna), probably in 1496 – 9.[10] Nothing is said about this painting surprisingly in the book, even by Koerner, even though whatever the iconography might mean, it clearly references attitudes to ‘moving on’ in space and time.

There is a winding path in this picture full of obstacles that the key characters in the foreground have already negotiated on their path from Sodom and Gomorrah – both of which (at some distance from each other) we see exploding in fire behind the characters, blitzed by avenging angels. Lot has been warned not to look back and he does this, not even tempted to watch the divine fireworks to his left side. The gaze of the daughters is somewhat towards the viewer but not with any consciousness of them. None of them follow the example of the wife and mother (always known to Scripture as ‘Lot’s wife’) who dared to look back from her travels to her geographical origin and to the past and is slowly being stilled into a black ‘pillar of salt’, though she resembles more the stylised weathered rock behind her.

Now Koerner tells us, in his essay that, in ‘learned culture of Dürer’s day, mobility (geographical and social) was an ambiguous capability’, and, as an attitude of mind had ‘negative connotations with inconstancy and deceit’. Yet art and craft requires mobilitas of hand, body and eye if an artist is to be revered, as they were in Italy if not always in Germany, then they needed like Lot to ‘move on’ and not keep looking back. Koerner concludes that:

The idea of a mobility passed from painter to viewer was widespread in the Renaissance. It belonged to a new estimation of the artist as avatar for the human capacity for change. Artists ‘change themselves beyond all human measure’, wrote Leonard Bruni (1370 – 1444) in his Life of Dante and Petrarch: ‘Through their genius [ingegno] they are excited and aroused by a certain power’ that moves them, allowing them to move others.

How much Lot and his Daughters capture the ambivalence of motion, careless of the past and quite unmoved by its loss (even that of wife and mother), I cannot say. I do not think we are asked to identify with the main characters for their avoidance and denial of empathy but we are shown that their motion is a necessity of their survival, as they carry symbols of work, possession of things and money (that cash box) into a new context.

Another possible allegory of this is Christ among the Doctors of 1506. Here, according to Dana Cowen in the exhibition book, ‘an inscription on a bookmark’ in this painting ‘boasts that the painting was “a work of five days”’. Panofsky, we are also told in the same place saw this statement as a ‘memorial to his mastery’ and the speed with which he moved as an artist. [11] The conflation of speed of the artist’s hand and the foci of this painting is clearly important. Indeed the foci of the painting are BOOKS and HANDS, which the detail in my reproduction of the painting below shows:

Having noticed this I do not know how necessarily to take this observation further except that Christ excels here because he requires only his hands to guide those who feel, because of way their crabbed fingers hook around books and text, have more authority. One (an old man revering the young and very feminine Christ) shuts and silences his book and gazes in awe. I spent a long time with this painting in awe too of Dürer’s handwork.

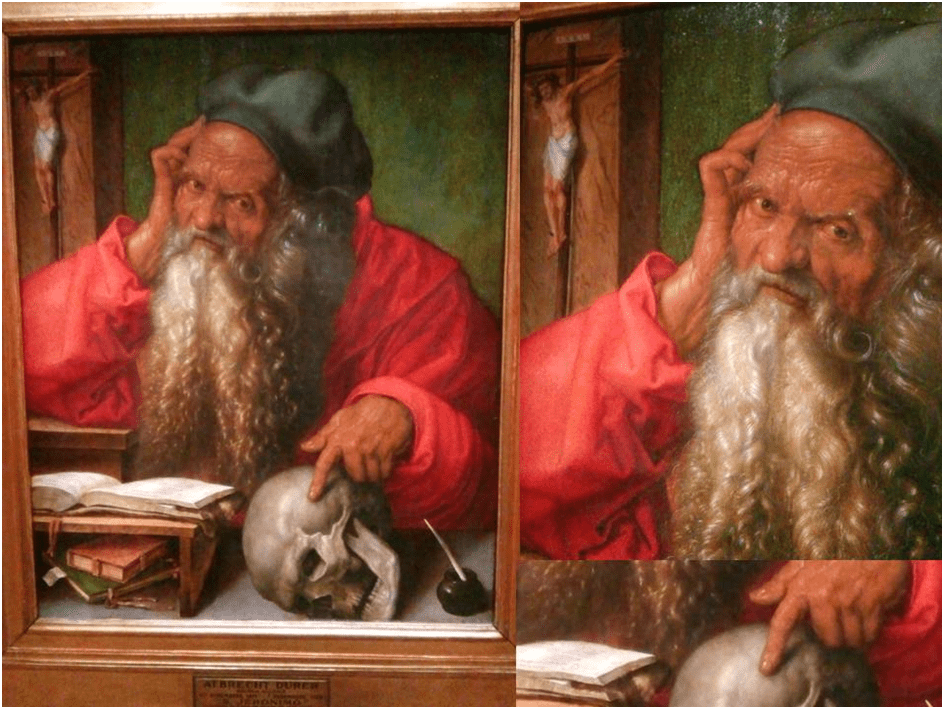

Had I more skill in the analysis of drawing I am sure I might have spent longer too with the silverpoint drawings dismissed by critics as interesting but, by implication, dull. Because dull, they almost certainly are not. But to say truth there is too much that would have overwhelmed had I spent the time each of the different elements in this exhibition required. Like the book, the last chamber of the exhibition is devoted to understanding Dürer’s innovations in the creation of an iconic image of St. Jerome. And i will end with thoughts on this. The essay by Astrid Harth and Maximilian P.J. Martens is possibly a necessary portal to the iconography of the 1521 Painting by Dürer since the same can be seen in pictures by other lesser masters. But those authors carefully give the case for reading the painting as an attack on ritual penance (the usual association of the Saint) in Roman Catholicism and embracing a more individualized meaning of continual penitence that did not require church intervention to be complete.

This feels convincing though what strikes me is the concentration on the living flesh of Jerome compared to the skinless skull representing death. There is a life in this old man and this fits with the knowledge we have that Dürer painted from a life model, whose sensed life and health mattered to him. His model, Harth and Martens tell us, was ‘a man “ninety-three years old and still sane and healthy” and that Dürer marked this on the painting itself.[12] It is as if, for Dürer, the fact of flesh has transcended sin. The Christ on the Cross too next to Jerome is incredibly realistic and painted to the life. Christ’s flesh is after all metamorphosed as scripture tells us from the Word of God, represented in the open and closed books beneath the crucifix. What one suspects is that, for Dürer, even the aging flesh of the old man and his rude health, important to Dürer as his note shows, transcends mere text. For though life is transient, it is too holy to bear scourge of the kind usually associated with Jerome. But even I think this reading strains credulity. However, I can’t get over the fact that being exposed to Dürer is being exposed to the demand to relate somehow to his need to build a relationship with his viewer – one that might change the latter’s life.

This was a wonderful exhibition. Just take it as YOU find it, please, because I am sure it will talk to you as it does to me – if with a different content.

All the best

Steve

[1] Susan Foister & Peter Van Brink (2021: 31) ‘Introduction’ in Susan Foister & Peter Van Brink (Eds.) Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist London, National Gallery Co. (dist. By Yale University Press).

[2] Kathryn Murphy (2022: 77) ‘Travel agency: To trail Dürer through Europe is to realise that his art relied on movement’ in Apollo (January 2022) 76-77.

[3] Joseph Leo Koerner (2022) ‘Dürer in Motion’ in ibid: 43 – 57.

[4] Jonathan Jones (2021) ‘Dürer’s Journeys review – magical sensual mystery tour is slowed to a sedate plod’ in The Guardian (Wed 17 Nov 2021 08.00 GMT). Available at: Dürer’s Journeys review – magical sensual mystery tour is slowed to a sedate plod | Art | The Guardian

[5] Murphy op.cit.: 77)

[6] Susan Foister (2022: 69) ‘Dürer’s Early Journeys’ in ibid: 61 – 75.

[7] Jergen Stumpel (2022) ‘Luther in Dürer’s Journal’ in ibid: 229 – 239.

[8] Till-Holger Borchert (2022: 94) ‘Albrecht Dürer and Portrait Painting in the Netherlands’ in ibid: 77 – 101.

[9] John Berger ‘Dürer: a portrait of the artist’ (1994: 8, first published 1985) in Albrecht Dürer: Watercolours and Drawings Cologne etc. Taschen, 7 – 13.

[10] Foister & Van Brink op.cit: 292 (‘List of Exhibited Works’).

[11] Dana Cowen (2022: 250f.) ‘Albrecht Dürer’s Late passion Drawings’ in ibid: 241 – 251.

[12] Harth and Martens (2022: 254) ‘Albrecht Dürer’s Iconic Image of Saint Jerome’ in ibid: 253 – 265.

One thought on “LONDON ART BLOG 1: Kathryn Murphy reviewing The National Gallery, ‘Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist’ exhibition for the magazine ‘Apollo’ says the: ‘exhibition with its rather perfunctory captions, would have benefitted from … glimpses of a stranger, more curious Dürer, restless, wandering, moving at speed’. This blog reflects on the possible pitfalls of art exhibitions in the great international art institutions based on single great ‘old masters’. It is based on a visit to it on the 9th February 2022 and the accompanying book. ”