‘Can and should we queer the past? Or is history – with all its ambiguity, misleading familiarity and unknowable possibility – already queer’.[1] So says Justin Bengry in a 2021 essay from a set examining the ‘theory’ of history. A consideration of the differences in telling ‘untold’ historical stories in two books: Paul Baker & Jo Stanley (2003 – refers to 2014 reprint) ‘Hello Sailor!: The Hidden History of Gay Life at Sea’, Oxford and New York, Routledge; & Stephen Bourne (2017 – refers to 2019 reprint) Fighting Proud: The Untold story of The Gay Men who served in Two World Wars, London, New York & Dublin, Bloomsbury Academic.

The subtitle of Stephen Bourne’s 2017 book, Fighting Proud is ‘The Untold story of The Gay Men who served in Two World Wars’. It is a great subtitle although it sounds much more like the kind chosen by a publisher rather than a writer given that no historian would claim that they are telling previously ‘untold’ stories in this rather simplistic way. Many stories are told but not retold after the times have passed in which they seemed to have interest and relevance to their re-tellers and/or audience. Stories about anything that occurs in a specific time and space either repetitively over a duration or only once are in profusion and some get necessarily neglected.

Some might say that is precisely the function of a historian to select from the available stories and assert their significance to their own time and place, and perhaps ours too. And then you realise that what makes a story available is some kind of commemorative process – whether as part of an individual or a family (or other group’s) memory or in concrete form in some archive – in hard copy or stored digitally. And this too involves processes of selection and sometimes de-selection of a kind we might call censorship if we are so minded. Sometimes if only by the use of scare quotes, Bourne shows that the sources of stories told at the time were biased to a certain interpretation of homosexuality as both effeminacy and, by implication, weakness.

See, for instance, this case cited with regard to ‘stories about “effeminate” servicemen’ in the Dover and East Kent News, that organ itself citing more official sources of story and interpretation: “Curious evidence, says the Military Mail… was heard regarding a young soldier’s strange effeminate ways …”[2] Of course such censorship could also act in families. My mother sometimes cut out from family photos the disfavoured family members (indeed had she been alive now her purpose could be served by specially designed software). Most importantly stories strain to type those selected for exclusion in terms of their unfitness: they are ‘strange’, even the evidence is ‘Curious’. The queer is that cut off from the norm it serves to define by being its ‘other’ and of which it will construct an ambivalent margin: just enough of a clarity to it to provide a ‘definition’ of the queer.

You don’t, of course, have to take any of this theme too far to see that it is impossible not to deal with any matter of historical ‘fact’ without some kind of theory dealing with two matters. First, of how facts are distinguished from fictions or lies or ideologies (since all of these are related, aren’t they Boris Johnson). Secondly, with how each item of any piece of those conceptual constructions is related or meaningfully associated with any other piece. In the end history cannot be a tale that is told without some epistemological underpinning I would further venture. And yet Bourne will have little truck with this kind of thinking and this for fairly noble reasons that we need to elaborate.

In a recent set of essays on contemporary theories of history, Justin Bengry draws the line between those who seek from history the ‘ancestry’ (as it were) of people who know define themselves as ‘gay’ or of a LGBT community. He points to ‘historians’, although naming only John Boswell, who claim that our ‘gay’ ancestors ‘share with us a common bond much stronger than other experiences and understandings of selfhood that might separate us’.[3] The aim is to intuit a LGBT community that extends through temporal as well as geographical space to ensure the basis of an identity that is an enduring, stable and intelligible in simple terms. And though the historical period dealt with by Bourne – covering the British involvement in the ‘World Wars’ of the twentieth century – relatively recent and therefore not so estranged from us as those engaging in sodomy in fifteenth-century Florence or the ‘gay subculture’ (according to Rictor Norton), surrounding the molly houses of eighteenth-century London, including Mother Clap’s establishment in Holborn, they can equally be seen as describing a very different notion of what constitutes ‘being gay’ to contemporary mythologies of gay liberation.[4]

For Bourne these differences would seem to be minimal and explained by the oppression of gay lifestyles by a censoring social system that even contaminated the sources of possible evidence of those lives by omission of them or misinterpretation. Sometimes the agent of those censoring offices were gay people themselves, especially, according to Bourne those from more privileged with economically and socially secure status, although not those whose security had been threatened by the necessities of war. Yet these stories were clearly not ‘untold’. Most of the evidence in this book has been published but as fragmented references that ‘have never been grouped together and published in one volume’.[5] Some sources are indeed well known such as the stories of Tom Driberg and J.R. Ackerley.[6] Others are of well known persons (such as Kitchener) where the ontological status of gayness is the issue and often decided in the most heteronormative way by belief in whether the male person ever had physical sex with other men (as if this in itself were self-explanatory which it definitely is not): ‘in terms of physical acts rather than by desire or mindset’ (in Norton’s terms cited by Bourne) or by self-identification or group affiliation, whether temporary or permanent.[7]

The purpose of all this would seem to be to point to people in history as examples of a kind of essential version of our selves, assuming for an unforgiveable moment that we are all ‘gay men’. Bengry makes this point in relation to studies of the eighteenth century mollies, men who performed sexually and ritually dressed as women in the molly houses: ‘Were they simply gay men in drag camping it up in the eighteenth century until state homophobia destroyed their subculture? …’.[8] That there is analogy between people in two separate cultures, times and spaces does not equate with an essential identity between the people between whom analogies are seen. And I think this is so even when we look at relatively recent periods of history, as I intend to do in a future blog on the forgotten North American queer novelist, Donald Windham and his links to the gay subculture of his set including Tennessee Williams, Paul Cadmus and George Platt Lynes ( I have already blogged on some of this group including Glenway Westcott in relation to matters of queer history). When Bourne talks about Kitchener we are inclined to find in him that which constitutes aspects of a uniform ‘gay’ identity, even if acting under repressive laws, mores and public display rules. If we have a ‘gay perspective’ we will not think like Kitchener’s 1988 biographer John Pollock.[9]

Yet however biased Pollock may be, with a ‘perspective’ of an ‘Anglican clergyman’ and fan of Billy Graham, he may have a point that seeking for ‘symptoms’ of homosexuality as a stable identity marker may not be fruitful, It is still worth questioning however how and why Kitchener did not meet certain heteronormative criteria: either in his long live-in relationship with Captain Oswald Fitzgerald (25 years younger than he) and a passion for antique domestic porcelain.[10] Because these circumstances are literally queer. And that suggests not that history reveals the a continuation of one category of identity, or character type but that we only see history properly when we look behind the norms we expect it to manifest. Bengry calls this ‘queering the past’, taking his lead from an essay by Matt Houlbrook from 2013: ‘Thinking queer: the social and the sexual in interwar Britain’. It depends on a starting point that accepts that the meaning of the category ‘queer’ (and hence its pertinence) ‘was “never self-evident, stable or singular”’. [11]

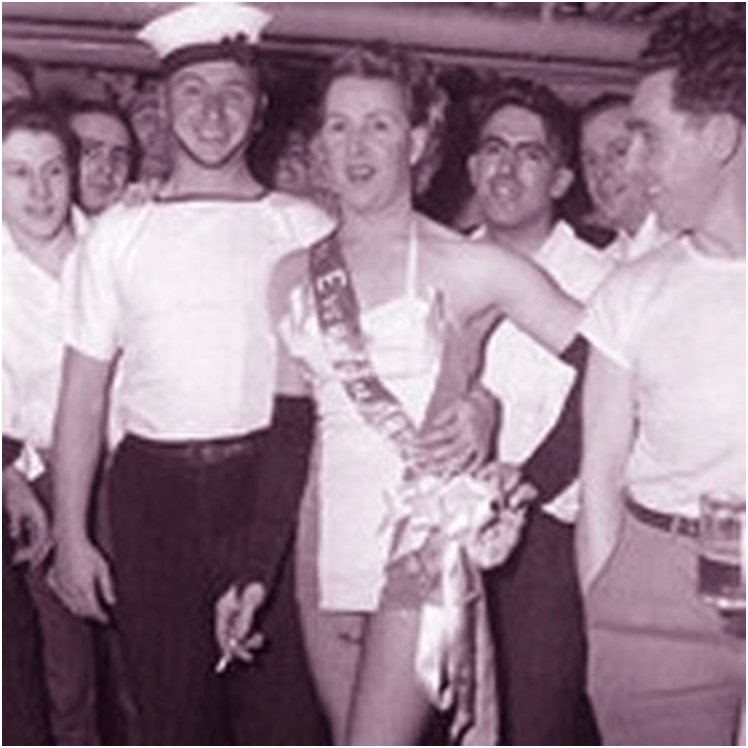

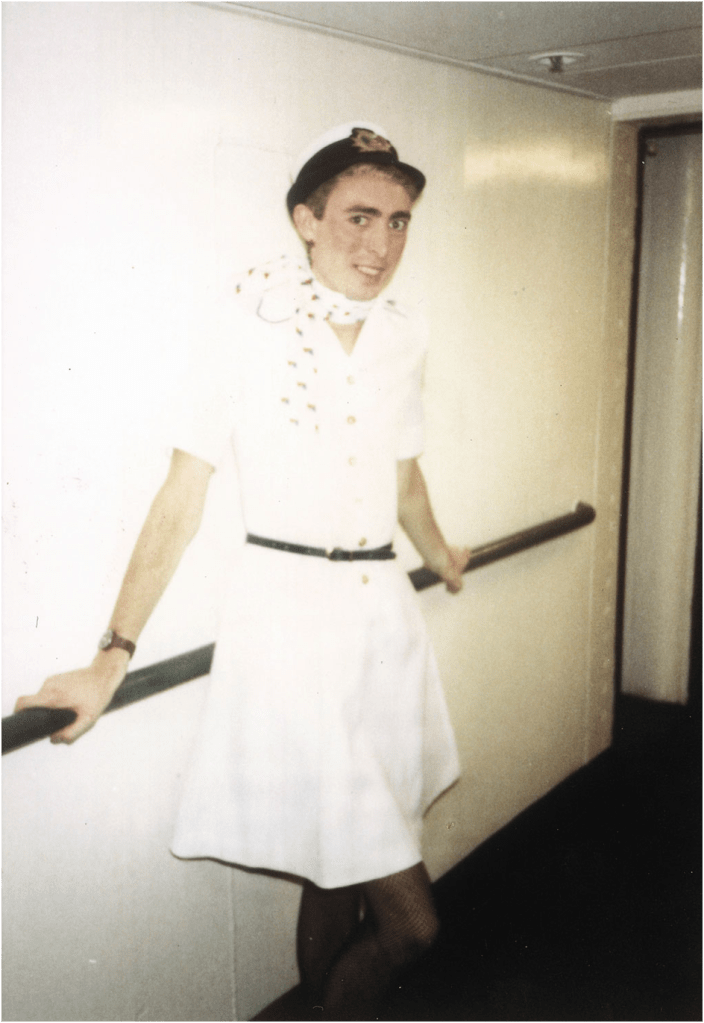

In my view Bourne does not seek to queer the past but to find evidence for continuing normalities within it, even if they were suppressed by homophobic legal, social and political mechanisms. Yet the difference in his findings of the markers of gay identity do differ considerably between the domains he looks at, say, to represent the period of the Second World War in his Part II of the book: ‘The Army’, ‘The Navy’, ‘The RAF’ and ‘The Home Front’. In each section he is drawn to the evidence behind the visible ones like the attraction to camp and assumes that what lies behind is more ‘real’ than that which fronts and perhaps disguises it. This is the burden too, though not explicit in either writer, of the plentiful evidence Bourne takes from Peter Tatchell’s examination of Dudley Cave, which often uses tolerance and liking for camp amongst an audience considered to be ‘straight’ to denote a deeper camaraderie. Now I am attracted to this since I, and my husband Geoff, met Dudley Cave when he ran the Gay Bereavement Project and gave us training in that topic when we ran Leicester Gayline (then working from our own home and telephone number).

But this desire to see oneself as part of a stable historical continuity may have more to do with a history of exclusion looking for validation from history than a recognition that the conditions in which people make their lives are not ‘of their own making’. And in making lives and selves many historical categories matter. By this I mean that a concept like ‘queerness’ is part of a network of intersecting multiple markers and determinants of self. And even concepts that intersect with the one we can call queerness like ‘labour, class, colonialism, capitalism’ and so on might (and are likely to be) ‘understood differently or inflected when considered alongside queerness’.[12] This matters because Bourne continually wants to show us that attitudes to gay men differed enormously between the working class and ‘educated’ middle classes of the period.[13] Yet alongside this he uses evidence of more open gay lifestyles, especially if they involved sex with multiple partners, from the educated middle classes mainly.

It seems to me that this is because Bourne did need to ‘queer the past’ and not make assumptions about it that connected him to it emotionally and conceptually, as I was tempted to do in remembering the ‘real’ Dudley Cave From Bourne’s chapter 7. In fact the ‘real’ Dudley I met is as much a construct of all the other memories of the wonderful and complex man. What convinces me about this is the use of evidence about John Lehmann, a favourite persona from history of mine. Lehmann is a figure who belongs to many ‘histories’: that of Bloomsbury and its ‘Group’, publishing and journalism and queer history (he appears in my blogs such as the one at this link). Bourne cites the fact that some of his evidence, that of G.F Green as a soldier dismissed from the Army, depends on its publication by Lehmann in Penguin New Writing No. 31. Now Lehmann did not do this merely because he published novel writing in his popular and cheap anthologies of the arts but because those anthologies were seen as political weapons to use the class mixes that occurred in the war to open culture to marginalised groups. Hence his interest in Ernest Frost as a queer, if not gay, writer, soldier and man of the everyday ‘people’. I have blogged on this already. Yet such links which inflect the meaning of class, and queerness are not made by Stephen Bourne precisely because of his commitment to an essentialist concept of gayness.

In the polar opposite camp (the word used advisedly) is Baker and Stanley’s Hello Sailor!. This may be because the latter book bears the marks of university educated and socialised authors, writing from conventions of their PhDs. in oral history, despite its delightfully popular style of writing and respect for their participants who spoke its evidence from their own lives. For them the class of people they wanted to investigate were possible only because of the time-limited history of the phenomenon of sea cruises for large numbers of people and a range of social classes, a configuration of working lives that mad such work exclusively male for a period and a more fluid conception of both sex and gender and their interactions. The queerness thus was inscribed across history not in the history of a group alone. It set out to challenge stereotypes of ‘gay seafarers’ and of the importance of the cruise ship as a liminal space. The concept of liminal space is possibly one of the most significant in tracing how to write and rewrite histories of identity, including sex/gender, sociality and sexuality, since it emphasises transitional rather than fixed experience – the very stuff of a possible ‘queer history’. As the authors say:

‘Queer’ in this case is set up in opposition to whatever is established as ‘normal’, a much wider category than self-identified gay men and lesbians. However … [queer theory] … has been accused of creating a form of academic discourse that excludes non-academics.[14]

Awareness of the latter danger however has made this book arguably as easily readable as Bourne’s book. Of course the concepts are more complex but i suspect that it is because complexity is the truth of reality, if truly seen from enough perspectives to be meaningful to all of us. It is in this book not Bourne’s that the terms from gay seafaring life like ‘meat rack’ and the dubious identity of the ‘winger’ are well defined and understandable as historically determined. The young ‘winger’, for instance, and his older seafaring relies on a relationship conceptually much hearer to that between ephebe and mentor, a teaching relationship that was open to sexual opportunities between adolescent and adult males in classical Greek history and is unthinkable in contemporary gay life where its abusive characteristics, involving power rather than sex are more obvious. Bourne does mention this phenomenon as an example of George Melly’s ‘same-sex liaisons’, without seeing its queerness in other terms, such as differentials of power, though Melly’s writing gives him that opening.[15]

For Baker and Stanley there is no standing back from features of life like this that have no strict likeness to contemporary gay lives but no direct equivalent. And this means that the analysis penetrates the language used by these men, including Polari, in which Baker is the academic expert. These relationships crossed boundaries much more often though it was that between straight and gay that was more porous than those between genders (women were absent largely), class, ship job status, and race.[16]

‘So, some gay relationships were with gay colleagues, but others were with ‘trade’ colleagues who were heterosexual but available during the trip. The Polari term for a seafarer who engaged in gay sex without identifying as gay, was trade omee.’ (They turned) ‘to gay men as substitutes for women’.[17]

The concept of a ‘sea wife’ only becomes legible from those facts of a limiting set of historically determined conditions. Hello Sailor! Is a joyous book because it does not assume we can understand by merely looking for sameness to ourselves (also determined historically but often invisibly to us as we live in them) but by understanding and working with the terms such by people who codetermined their lived histories. This book makes it clear that people like me, a radical GLF and GAA member, who often picketed queer venues, especially those which used gender crossing as eagerly as oppressors like W H Smiths who refused to stock Gay News on moral grounds.

There is a sense in which this less flexible radicalism, often justified as an alliance with feminism which these days I find naive, was responsible for historical change but maybe no more than the death of cruise ships and more equal opportunities at sea for women.[18]

Of course we should be reading both of these books but I find the one I deal with second, the older one, more appealing as creating a history in which I can not only identify, but only with aspects of it, and which knowledge of will help to develop alternative and more just futures that do not rely on binary divisions between camps of people.

All love

Steve

[1] Justin Bengry (2021: 63) ‘Can and should we queer the past?’ in Helen Carr & Suzannah Lipscomb (2021) What is History, Now?: How the past and present speak to each other’ London. Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 48 – 65.

[2] Bourne (2019: 14)

[3] Bengry (2021: 50)

[4] Latter is described in ibid: 54f, For the former see my linked blog.

[5] Bourne op.cit.: xv

[6] Ibid: 119f, 129f.

[7] Ibid: 8

[8] Bengry op.cit.: 55

[9] Bourne op.cit.: 8

[10] Ibid: 8f.

[11] Bengry op.cit: 54 cites Matt Houlbrook (2013) ‘Thinking queer: the social and the sexual in interwar Britain’ in Brian Lewis (ed.) British queer history: New Approaches and Perspectives, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 134 – 164.

[12] Ibid: 59

[13] For example Bourne op.cit.: 46f.

[14] Paul Baker & Jo Stanley (2014:19) ‘Hello Sailor!: The Hidden History of Gay Life at Sea’, Oxford and New York, Routledge

[15] Bourne op.cit.: 67f.

[16] Baker & Stanley op.cit.: 92f.

[17] Ibid: 94

[18] See ibid; 217ff.

3 thoughts on “‘Can and should we queer the past? Or is history – with all its ambiguity, misleading familiarity and unknowable possibility – already queer’. So says Justin Bengry in a 2021 essay from a set examining the ‘theory’ of history. A consideration of the differences in telling ‘untold’ historical stories in two books: Paul Baker & Jo Stanley’s ‘Hello Sailor!: The Hidden History of Gay Life at Sea’, & Stephen Bourne ‘Fighting Proud: The Untold story of The Gay Men who served in Two World Wars’.”