“Being a star in our own Twitterverse, sometimes resplendent, but more often fading (however continual our hard tapping may be), is all that may be left of the desire to belong to something that is more substantial and larger than our self”. A blog based on Leopoldstadt, the new play by Tom Stoppard seen 27/01/2022 live-streamed to many venues (I was at the Gala Theatre, Durham) from the Donmar Warehouse.

Being a star in our own Twitterverse, sometimes resplendent, but more often fading (however continual our hard tapping may be), is all that may be left of the desire to belong to something that is more substantial and larger than our self. Artists are fortunate in that their skills can be used art to imagine that populated and fulfilled space and embody it with means appropriate to them so that it becomes an object we can share. I think Kenneth Branagh’s film Belfast (about which I have blogged) did that to some degree with an idealised form (because divorced from the realities of actual conflicts) of that specific socio-cultural and geographical place. Tom Stoppard’s Leopoldstat is a much more complex work of art however.

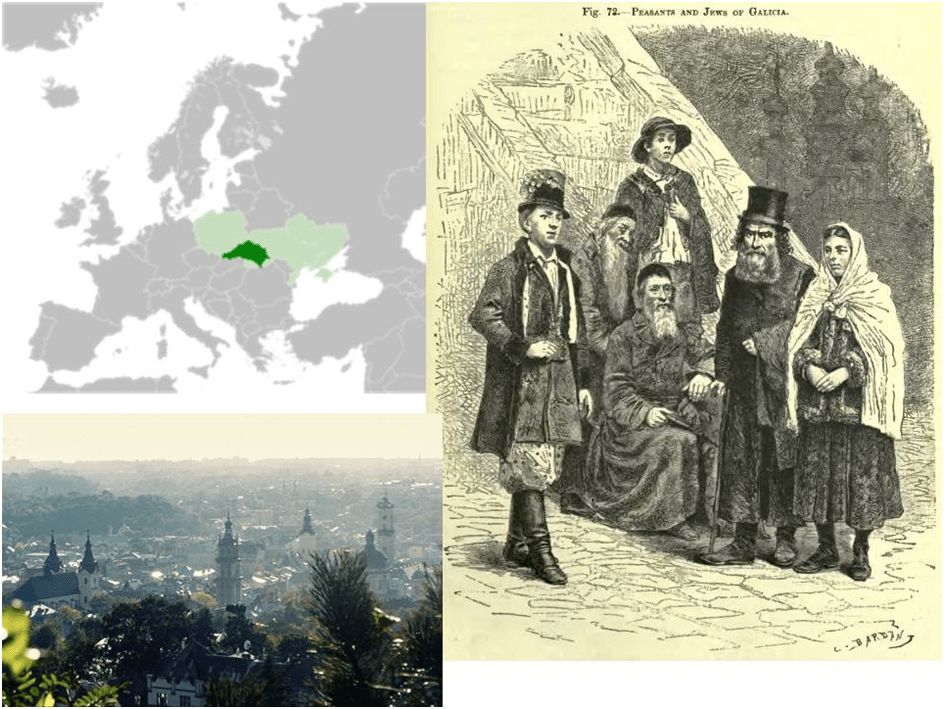

Its title also names a space and as a play enacting scenes in imagined versions of ‘real’ times and spaces, it is ‘set’ in the well-known district of Vienna named Leopoldstadt, which housed Johan Strauss, Sigmund Freud, Gustave Mahler and Carl Schoenberg, to name but some of the internationally known and canonical writers mentioned in this play.

But in developing this theme one realises that, even just as a space, Leopoldstadt is already fragmented by contradictions implicit in its history. In Scene One it is mentioned in terms of being a place of confinement, the ghetto of Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire set in 1899:

But fifty years ago you … couldn’t up sticks to come and work in Vienna; but if you lived in Vienna you lived in Leopoldstadt, you wore a yellow patch and stepped off the pavement to make way for an Austrian.

A space of confinement and oppression has however some secure places. This is so, at least, for the Merz family if not for unseen ranks of working-class Jews. Their name, Merz, has assonantal connection to the German for commerce and have risen in class and status ‘in one lifetime: ‘My grandfather wore a caftan, my father went to the opera in a top hat’. [1] Moreover, Leopoldstadt has changed its nature apparently to become what it now is again (though a ghetto again during Nazism before its destruction), the synonym of the Viennese arts. For Hermann, a factory-owner still, this is intimately linked to the Jewish character of Leopoldstadt, though an ethnic identity associated now with ‘liberty’ of religion amongst the Jewish population as a reflection of a more genuine liberty of space and ownership of those arts – producing AND consuming them:

We buy the books, we look at the paintings, we go to the theatre, the restaurant, we employ music teachers for our children. A new writer, if he’s a great poet like Hofmannsthal, walks among us like a demi-god. We literally worship culture.[2]

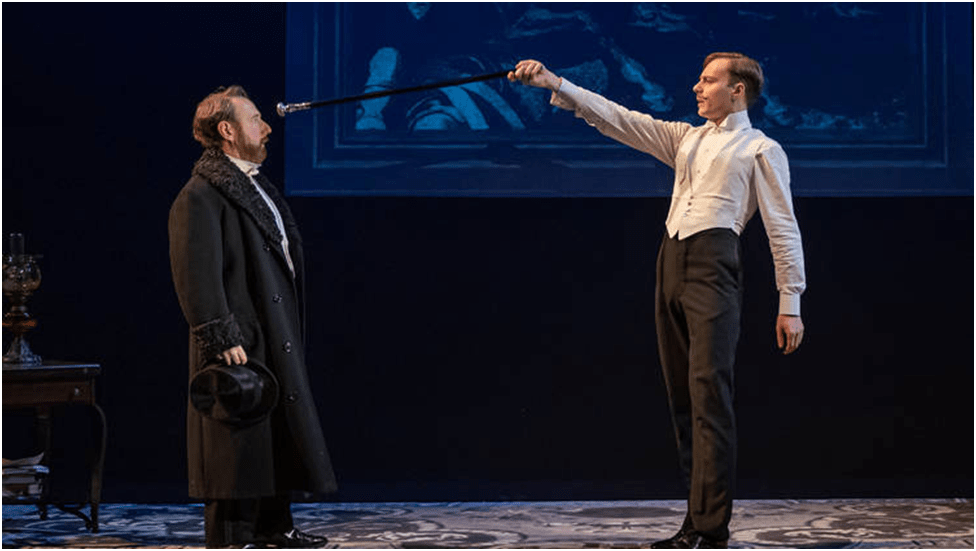

This is evidence enough perhaps to show us that spaces both relate to communities of interest or ethnicity and can imply both controlled subjugation as a form of imprisonment or entrapment and perhaps its opposite – a space you control or own, or think that you do so. You have to say ‘or think that you do so’ because this is precisely the revealed history of the play. By scene 8 set in the same room in the same district but in 1938 Austrian pre-configurations of German Nazism were extending definitions of who is Jewish to those of ‘mixed-race’ and using that too as a qualification for exclusion from cultural and economic ownership and control of one’s life: ‘No mischlinge in journalism, the creative arts, the performing arts, literature …Culture is verboten’.[3]

Later in the same scene a ‘Civilian’ (meaning a native Austrian Fascist with a hankering to be addressed as ‘Herr Doktor’) enters this space, which he names a ‘nest of yids’, saying to Eva: ‘Did you think you were Austrians, you old parasite bitch?’, to which Eva replies with restrained (in both senses of the word) dignity: ‘My son gave his life for Austria, and he was proud to do it’.[4] These are painful scenes totally dependent on the sense of how it feels for space you felt you owned to be violated – a kind of rape.

If I return again to my theme it is to stress that this ‘something that is more substantial and larger than our self’ I name in my first sentence can sometimes feel to be the liberation of a true and hidden identity with its connection to an identity of community – whether that be the Jewish race or the fellowship of the arts. But that this same sense of space can sometimes feel too like an entrapment, something no person who is black, brown, disabled, poor, a woman or queer does not also know. Entrapment comes when your ‘identity’ is an object of policy as Paula Freire called this situation in application to the ‘wretched of the earth’. We choose identities then with caution by necessity but the choices are not always ours to make, whatever the determinants and the relative hardness of their evidence.

Much is made in the reviews of the personal nature of this play, given that Stoppard discovered the full extent of his Jewish origins only in the 1990s and his links to a family very like the Merz family. The director of the play, Patrick Marber, in a prologue to the live-streaming of the play noted that, as a director, he did not pursue Stoppard for a personal story however and stuck to the narratives and their potential within the text. Of course a produced play is more than text and Stoppard chose Patrick Marber, a writer himself who had first produced Travesties, out of professional respect, as revealed in the same source. Marber has added enormous value to the play together with his collaborators. For instance a semi-transparent gauze screen is used sometimes to semi-obscure the scene and mark, by projecting the numbers onto it, the vital changes of date in the play as family members age and/or die or the characteristics of the society in which it exists (and is defined) and its politics changes. And onto this screen images are projected.

One of the most moving effects of the images screened thus – dramatic in the sense that it uses the efficacy of drama to reveal ‘facts’ and only gradually open up their significance and impact – is the projection of a hand-written version of the Merz family tree. At first its contents seem impossible not only to grasp but even compute or match with the persons we see on stage. Indeed the complexity of understanding intrafamilial relationships in such an extended family become one of the features of some of the speeches as characters misunderstand these relationships. only in the final scene, in 1955, do we realise this image is of a note handed to Leonard by Rosa as a way of understanding that tree – now that most of its members are dead. the play ends with the reading of the tree with summations of how each died, it is not only that this means the words Dachau and Auschwitz ring in our head and heart at the end of the play, but also that others died by suicide as the completion of a form of intense survivor guilt.

Onto this gauze screen too appears moving or still images of places and times in and out of Vienna or in places mentioned. As I have noted the final lines of the play reiterate the names No traversed by the characters presently communed on the stage.

And these places extend geographically and historically into the future in the discussions of places where a Jewish homeland was once conceived. For instance in one of the many references to the ways in which the career of Sigmund Freud was hampered by his being a Jew and the novelty and nature of his ideas Hermann answers Ernst’s idea that, in other circumstances, Freud would be ‘extraordinarius by now’ by saying:

He should go to Argentina. He’d be a professor in no time. … Or Africa. Palestine is a lost cause as long as it’s ruled by the Ottomans. Or Madagascar! They say there’s plenty of room for a Jewish state in Madagascar.

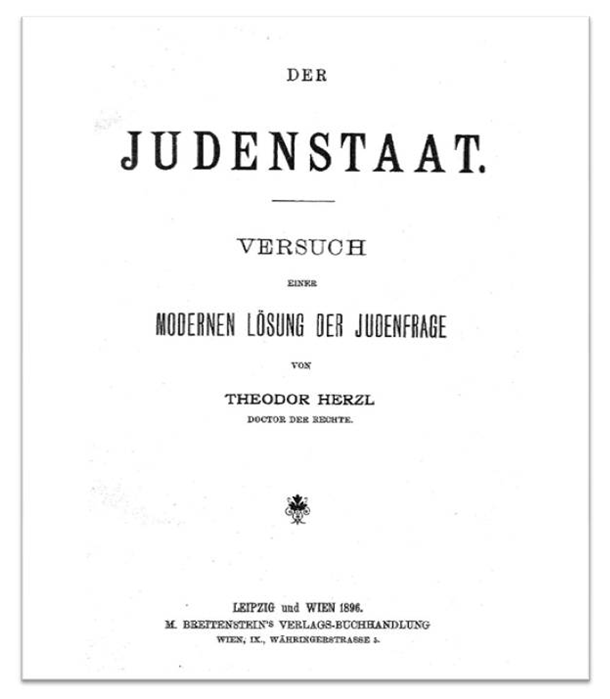

On stage the characters are handling a book. Stoppard does not say which book and you are hard-pressed if, like me, you like to read the titles of books held by characters, but one (referred to anonymously too in Stoppard’s stage directions as a ‘a thin “book”, a pamphlet of 80 pages’) is later referred to in conversation between Ludwig and Hermann, and it is Theodore Herzl’s Der JudenStaat, published in 1896 two years before the play’s first scene is set.[5] Ludwig says:

The only welcome Theodore Herzl’s little book received was in the anti-semitic press. A state for the Jews? Good idea. Get them out of here! The Jewish press was offended naturally. … They have enough trouble without making a song and dance about being different when sameness is the goal.[6]

My point is that that the theme of a Jewish state and the growing historical potentials for it mentioned throughout the play as history develops (to the Balfour Agreement, for instance, and the eventual role of the United Nations in establishing Israel) are all about this desire for a bigger community and space in which to identify with something greater than our self. This is meaningful of course in terms of the play’s exploration of the identity Stoppard discovers in 1990 when he discovers his original Jewish surname like Leonard Chamberlain (who was named Leopold Rosenbaum in the previous scene and was a young vulnerable boy with a bleeding wound to his hand from grasping a broken cup in fear of the Nazi in his home) does together with the oppressive attitudes to his own past self: ‘She wanted me to be an English boy, I didn’t mind. I was pleased. … We were top country’.[7]

But I need to make another point about Stoppard linking himself to something more substantial and larger than’ his ‘self’, which is the idea of him as a literary artist – in particular a maker of books.

To do so I want to return to the opening scene where three books are so self evident in the scene and likewise whose titles are hard to see clearly if at all, but which can be intuited from the conversations in the room. It is clear Stoppard wanted this effect from the stage direction that mentions them that I have already cited in relation to Der Judenstaat. In each case Stoppard refrains from naming thee books, which in a stage direction, and in the eyes perhaps of a person responsible for resourcing stage properties is less than helpful of the playwright, since the theatre audience does not see stage directions. Here is the descriptive direction following on from the part already cited.

Eva is confiding scandal to Gretl over another small book.

Ernst is talking to Ludwig about a third book.[8]

Why the mystery? What these books are is in fact important to know in terms of the conversations in the book and their relationship to this theme. The second ‘small book’ is a play text and knowing what it is will be vital in understanding the sexual imbroglio which consumes Eva and Gretl, where the older Gretl is actually having sex already with the man Eva is confiding her sexual attraction to, and which fact Gretl’s husband Hermann will shortly discover[9]. Indeed he will use this discovery as a means of unfolding of the plot in a way only revealed in the last scene (but no spoiler here). The book the two ladies injudiciously read with Fritz, the Austrian soldier over whom both lust, is a play by Arthur Schnitzler.[10] Hermann discovers this fact by finding Ludwig’s copy of the play at Fritz’s as left by Gretl: ‘You have his copy of Schnitzler’s new play, privately printed and inscribe to Dr. Ludwig Jakobovicz’.[11]

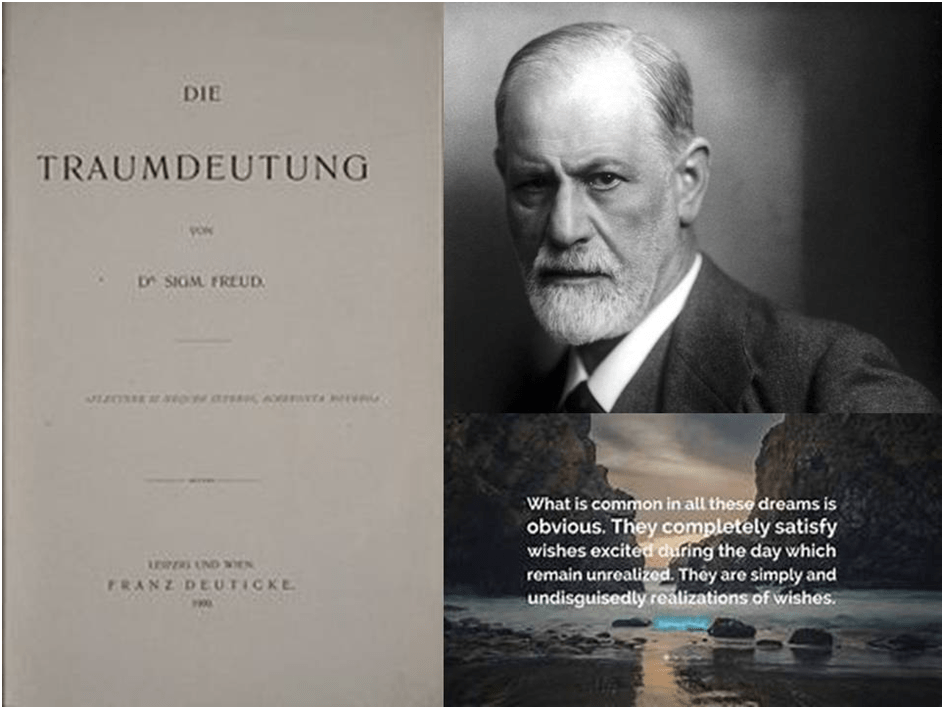

The third book is discussed, if rather gnomically, from the play’s beginning when Ludwig says of it: ‘Hysteria, neurosis … the more modern the diagnosis, the more the treatment returns to its origins in the priesthood. So, yes, the interpretation of dreams, why not?’[12] This theory of Freud’s is referred to again in Scene 8 more knowledgeably: ‘A dream is the fulfilment in disguise of a suppressed wish’, to refer to the vulnerability of Jews and even Freud’s puzzlement about why they are the object of a barbaric hatred of ‘culture’, throughout associated with Jewish people.[13] The book is clearly Die Traumdeutung (The Interpretation of Dreams). Indeed it is the one title I glanced enough (I am persistent) to be sure of that.

There are constant references to dreams in the play. Some intersect with the other books I mention, especially Der Judenstaat, but I think what interests me most about the three books that open the play is that they link the play (Stoppard’s last play (as he insists) and ‘masterwork’, as others insist) to the ‘worship of culture’ which Stoppard clearly sees as his main inheritance from his Jewish past, from the evidence of the play.[14] Such an inheritance is also a communal space populated by the artists of the past, including that scientist of art Sigmund Freud and the interpreter of Gustav Klimt, the artist who dominates the play through the persistence in the scene or even talk of his imagined portrait of Gretl.

But Klimt is also characterised by his ability to shock the Austrian bourgeoisie, Jewish and non-Jewish, by ‘supporting art which decent Austrians found nonsensical and offensive’, much as Freud thought Arthur Schnitzler also did.[15] Ernst in referring to Freud’s escape to London says: ‘I thought Freud was on to something from the beginning. The evidence was there to see, in the work of writers and artists. … – do you remember Klimt’s ‘Philosophy’ painting?’[16]

For Stoppard at 82, when he finished this play, I think the inherited space from Judaism still included n understanding of Zionism, for right or wrong in his view, but I am inclined to agree with Robert Cohen in his thoughtful discussion (use the link in the footnote to see his textual evidence) of how Zionism is sidelined in this play, where notions of Jewishness as a cultural space of enormous tragic experience and likewise hope is not. Cohen writes in 2020:

I’d love to ask Sir Tom if his decision to play down Zionist themes in the Leopoldstadt was a conscious or unconscious decision. Why does no character in the play adopt a Zionist disposition? Perhaps Israel and Zionism were never central to Stoppard’s late in life discovery of his Jewish heritage.[17]

Yet though I think this is the case, it is also clear that Stoppard wants us to know that the vanished Jews of Vienna were betrayed by those holding potential safe spaces for them at the time, especially the United States who never filled its quota though it was not a quota enlarged on humanitarian grounds. The United Kingdom comes off little better in the silly and easily exposed nationalistic naivety of a country that might only allow immigration from refugees that are either rich or famous or, at least as these characters think, there servility. One middle class gentleman says he is training as a valet because the ‘British consulate is going to let in Jews in domestic service, because of the army taking what there was’. I do not know if this is a true story.[18] However, it is true that quotas for refugees were incrementally limited as the need grew in the UK as well as the USA.[19]

The fundamental mistrust of the Establishments of the Established Nations may well explain, if Cohen is correct, why Zionism gets no stronger evident support in the play but my main conclusion is that Stoppard is looking to the connection between Jewish people and creative thinking in politics, painting and literature. This is I think why the play begins at the cusp of a new century (1899-1900) and in the light ‘three books’ by Jews which Ernst expresses thus:

There’s something about a theory being published at the very beginning of a new century. Like an augury. Like the curtain going up on something.[20]

This seems to me like an image that predicts Stoppard’s career and thankfulness for it, to his ancestors and their complex mixed traditions. It is a more certain prediction than that Ludwig will solve his favoured mathematical hypothesis. And hence I suppose the play is about its own achievement, which its best critic, Andrzej Lukowski (in Time Out) describes thus: ‘The scale of the story, told mostly in dialogue, is breathtaking, the work of a master, and if a lot of exposition is required to further this then so what?’[21]

See this play if it is repeated or made available on DVD. I loved it, though the conclusions I make.

All the best

Steve.

[1] Tom Stoppard (2020: 21f.) Leopoldstadt London, Faber & Faber

[2] Ibid: 22

[3] Ibid: 68

[4] Ibid: 78

[5] Stage Direction ibid: 4

[6] Ibid: Loc 460.

[7] Ibid: 94

[8] Ibid: 4

[9] Hermann in fact discovers that the young Austrian soldier, Fritz, considers (this is a very old anti-semitic trope) the circumcision which identifies a Jewish male as a feminisation of a man and hence sees their wives as ‘voracious for sex with a gentile, for anatomical reasons’. (ibid: 32).

[10] I had assumed it was La Ronde, because of its notoriety, but this was not published in 1899 when the play opens (published in Vienna in 1903) though it could be his earlier plays dealing with both sexual morality and anti-Semitism. See Arthur Schnitzler – Wikipedia. However the copy read is a privately printed one gifted to Ludwig by Schnitzler himself and thus could be La Ronde. I do not know.

[11] Ibid: 37f…

[12] Ibid: 6

[13] Ibid: 72.

[14] See for instance Nick Curtis (2020) ‘Leopoldstadt review: Tom Stoppard’s new masterwork is an early contender for play of the year’ in Evening Standard (13 February 2020) Available at: https://www.standard.co.uk/culture/theatre/leopoldstadt-review-tom-stoppards-new-masterwork-is-an-early-contender-for-play-of-the-year-a4360871.html

[15] Stoppard, op.cit.: 72

[16] Ibid: 71f.

[17] BY ROBERT A.H. COHEN (2020) ‘Tom Stoppard’s first Jewish play leaves Zionism offstage’ IN Mondoweiss: News and Opinion About Palestine, Israel and the United States ( ) Available at: Mondoweiss – News & Opinion About Palestine, Israel & the U.S.

[18] Ibid: 71

[19] See ibid: 101

[20] Ibid: 12[21]Andrzej Lukowski (2021) ‘Review’ in Time Out (Monday 2 August 202). Available at: https://www.timeout.com/london/theatre/leopoldstadt-review