‘.. a streak of normality and even banality, which assumes its own surreal tone. Love letters to the past are always addressed to an illusion, yet this is a seductive piece of myth-making.’ (Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian 21 January 2022). ‘If Belfast had been rolled round in the dirt and broken glass, it might have made for a more powerful experience’. (Christina Newland i 21 January 2022). Even if we accept that art owes a debt to truth, what kind of truths must it tell and / or show in order to be great art? Steve reflects on this in the case of cinema films that wear their search for excellence of a kind on their sleeves. The reflection happens around a case study of Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast (based on seeing it for the first time on 21st January 2022 at the Odeon, Durham and two reviews).

It was clear from the beginning that, though ‘The Troubles’ in Northern Ireland were the background of this film set in and entitled Belfast, as they were of the period of actually growing up a liberal Protestant in the city of Belfast for Branagh, they were not going to be its subject or raison d’être. A more important indicator is that the film starts in full colour showing important features, including the huge crane Goliath that has served as the focus of a major BBC TV series and thus is well known to current UK audiences before morphing in a rather beautiful way into a black and white shot of the city in 1969 where we suddenly become aware of the careful mimicking of the appearance of working class Northern Irish people. These people are both Protestant and Catholic though, of course, how in reality it is possible to tell these groups of people apart? This question becomes part of the film’s focus and its ethical core in fact. If any part of this theme is important it is true that these populations were forcibly divided in that period by the actions of Protestant paramilitaries as a response to human rights protests from the Catholic population.

The key symbol of all this division ought to be the wall or barricade that divides the street on which we are focused. On this street lives Buddy and his family. Buddy is the boy played by the amazing Jude Hill and he is the heart of the film and its sentiments. He clearly represents the vision and growing pains of young Kenneth Branagh). But this barricade is more complex. I wonder though if many viewers get that. This wall is erected initially to protect the mixed population of the street from paramilitaries attempting to scare off the Catholics on this street, although clearly that is not how its function will remain as the key representative of those latter men (all men by implication in this film) Billy Clanton (played by the quietly talented acting wizard Colin Morgan) takes a hand in things. It’s important we remember this or we will fail to see the significance of the fact that it is the British Armed forces that break down the barrier and thus appear to side with Unionists over Catholics. Whether this was just an appearance is a moot point and only one of the complex and contested features of the history of that period that are not addressed in this film.

The Idea that Protestant paramilitaries were empowered only by the thugishness of a few men who went wrong is a problematic one in looking at the contested experience of the Northern Irish population. This would be equally the truth of Catholic populations and their relation to Catholic paramilitaries. There were terrible controls exerted on their ‘own’ populations of course by the paramilitaries (the practice of kneecapping for instance) but to conclude from this that their rule was entirely by force is clearly inaccurate, on both sides. But these are niceties of historical truth and interpretation that lie beyond the film’s remit, which tends to represent the ‘Troubles’ (without also arguing whether they should truly be called a civil war) by techniques that make them a confused background to a main character. This is often by having the camera circle around a central character who is, in that moment, seen as neutral to the conflicts around them. At one moment a camera circles Buddy three times holding him constant in its gaze as the business of those around them crossing the background in violent gesture adds to the confusion. This technique is one of those who creates a group of characters held to be, in essence, outside the conflict except as its passive victim, although this ethical position is one Buddy must learn through the film’s process.

Very often the camera eye holds a central person or interaction and reduces all else to the criss-cross of motion in this way and thus erases their role in the motivation and historical scenario around them. This phenomenon leads Christina Newland, the severest of the film’s critics, to see Branagh as reducing political history to filmic technique aimed at the most stereotypical of emotions, that she, for one, clearly does not value: ‘set against the backdrop of The Troubles and shot with a sterile distillation of art house cinema influences, it is effective at pulling at the heartstrings’.[1] Nothing in Belfast then can be further than truth as Newland sees it. Instead she insists that ‘director Kennet Branagh has been working at making a masterpiece’. Moreover, she infers the lack of truth in such characterisations is not only of the truths of socio-political history, it is untrue to genuine emotion, other than a sentimental version of such emotions. This is a damning judgement that goes beyond seeing the film as ‘flatteningly simplistic’ though that is bad enough.[2]

Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian however sees much in the film as an illusion, covering I think both the portrayal of civil unrest and conflict but also notions of family and other loving relationships. Family is clearly important as an idea and structure of feeling in the film and this idea seems in this film to be being rescued as the icon of our common humanity. This symbol is artfully and skilfully communicated and emotionally true enough at some deeper psychosocial level to be, Bradshaw infers, to be of the nature of a myth: ‘Love letters to the past are always addressed to an illusion, yet this is a seductive piece of myth-making’.[3] Clearly he, like Newland, accepts that this film grows out of the personal life of its director in ways in which accuracy to the social realities is relatively unimportant, What is important is how familial attachments acted as psychosocial drivers in Branagh’s own past. However, these drivers are so well handled in the film’s art that they seem like a common origin myth of how growth occurs in young children, although perhaps, I think, only boy children.

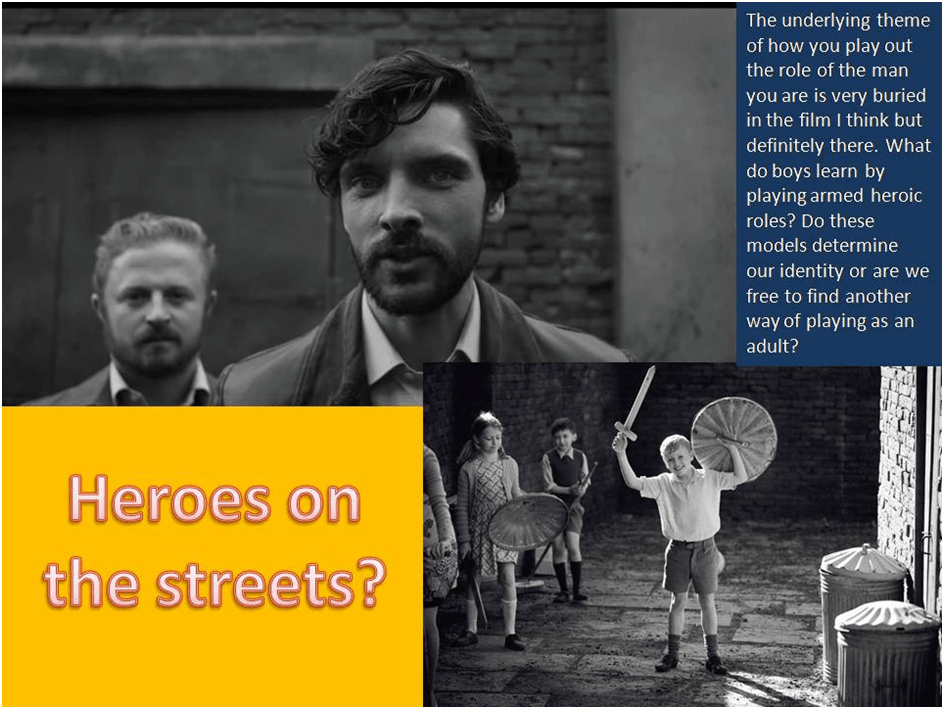

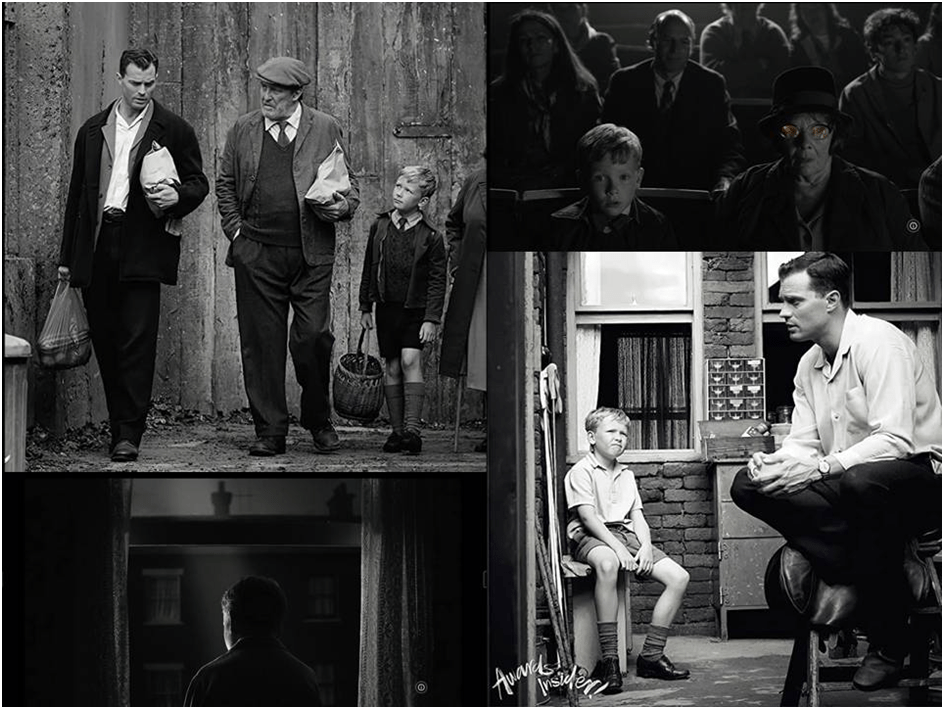

I certainly think my summary above captures somewhat what appears to be Branagh’s intention. The filmic technique so often emphasises that a boy’s point of view is essential to what we see in the film. This is done beautifully and subtly. However, it’s worth starting by looking at scenarios wherein there is an obvious desire to make the nature of a boy’s gaze an object in the film. Look at the collage of scenes I select below:

Sometimes, of course, Buddy just looks through windows, as he does in one of these examples. However, there is also throughout a constant use of a kind of technique by which the boy’s gaze is important in the meaning of scenes in which we see him. For instance in those cinema shots wherein he, together with family members, stare out of the film screen we as viewers gaze upon at what, in the narrative of the film, we must imagine to be a film screen or proscenium seen by them. In one occasion Buddy sees a play where the role of Granny (the superlative Judi Dench) is to demonstrate a naïve audience member. She is naïve because she converses through a scene that is being enacted before her at which, were we an informed audience, we ought to just look. Indeed at points the narrative focus changes from the boy and appropriate family members looking at a screen to the screen they are actually watching. I want to reflect on this later and especially the relevance of the shift from seeing the lookers in black and white and the film screen they see shown now to us in the original film image coloration techniques of the time – the things we now summarise as Technicolor for instance. But here I just want to see how the viewing gaze is valorised in this technique.

And the gaze characterises Buddy’s relation to others and especially male role models (from his family largely) such as Pa (Jamie Dornan) and Pop (Ciarán Hinds). The latter is Buddy’s grandfather and ‘Pa’s’ father. Yet what the affectionate names mark is that to Buddy, and for us, these men are their patriarchal family role and especially that that relates the men within it in a continuing genetic line. In the still in my collage we see these three males together. Buddy is of course modelling their behaviour but his key purpose is to gaze at them in order to do this modelling and to understand what the interactions between men ideally are and mean. It is an even more intense gaze that Buddy uses to look at Pa in the scene in the back yard, where Buddy finds it difficult to know what the role of fatherly provider might mean and why it might take that key male away from him. But the gaze also accompanies Buddy’s learning about his role as a lover in a heterosexual relationship and both Pop and Pa at different times advise on the role of mutual love between boy and girl and model it in their often childlike play with their own relationships to their wives. Pop and Granny so often revert to a kind of childlikeness),for instance. There is no doubt in my mind that heteronormative relationships have mythic status in this film and drive the key subplot of Buddy’s development – his affection for a young Catholic girl, Catherine (Olive Tennant) whose passivity and stereotypical behaviour render that character somewhat bland (a pity for an early role for David Tennant’s daughter) – something Granny and Ma (Caitríona Balfe) definitely are not. In my view Catherine bears all the affects of the weakness of choice of a mythic narrative strategy in the film.

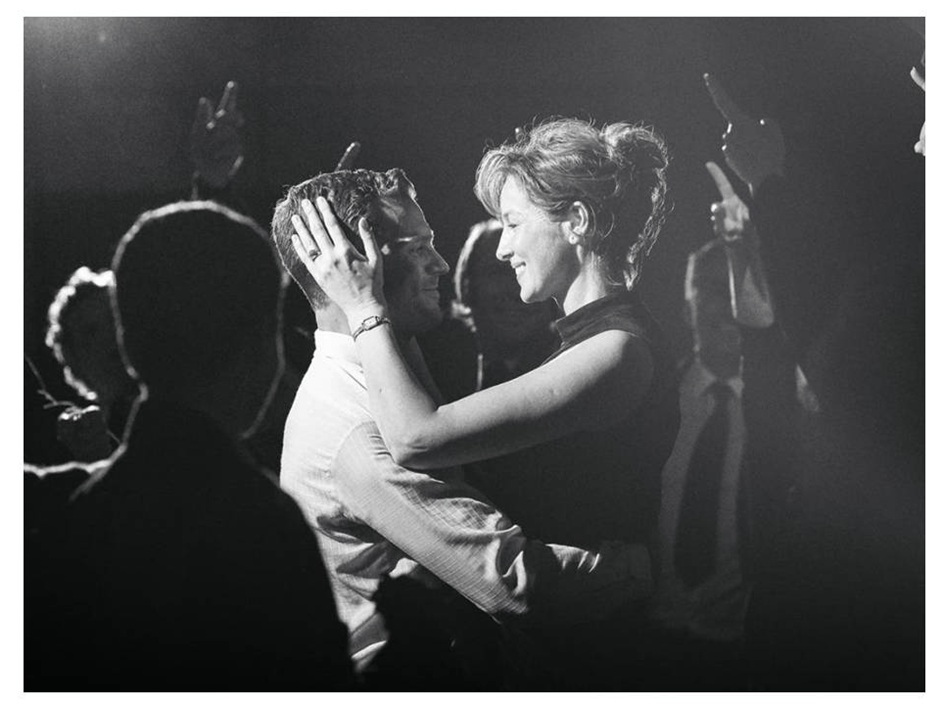

One of the most amazing scenes is of the reunion after marital distance of Pa and Ma in the local club. Look at it here:

It is one of many scenes in which the brilliance (and photogenic quality) of Dornan and Balfe is made a cynosure of the film viewers’ eyes. Here the characters play in the light of a couple idealised and idealising the redemptive power of a heterosexual match. It is powerful and mythic but I choose this still mainly so you might see how your own gaze as a viewer on the charisma of the couple is mediated by Buddy’s gaze, which forms the shadow obstructing our view but at the same time training it on his parents as an example of the power of heterosexual marriage and potential. What he learns from this model is that that he might find (with Catherine if she is the right girl) the same in his own life. Indeed Pop says to Buddy that, if he goes to England, Catherine will probably still be there when he returns. This implied scenario for girls is not a very attractive one we might think – to be She-who-waits-for-Him. That there is an underlying sexism and heterosexism in this needs to be noticed and may surprise us given the fact that Branagh has sometimes done great work with the queer potential in some relationships – in Peter’s Friends for instance).

However, at the same time, I want to forgive Branagh for feeling that it is necessary to reach back into the mythic illusion of many boys in which their parents and grandparents may have seemed all the roles needed to fire the inner desire for their future desired ‘normality’. This process seared the lives of those who us who are queer but we might also have to admit that it also lingers on as a source ‘myth’ through which we value love in all human relationships.

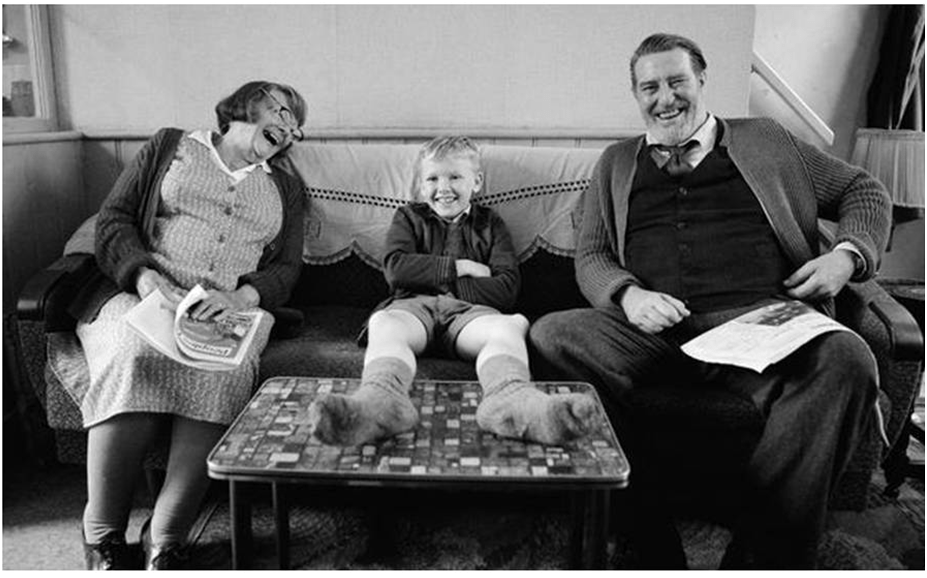

The relationship between Buddy and his grandparents is particularly important. In one beautiful sequence he sits between them as if the sole meaning of their lives in its process of long unfolding is him. As a directorial shot it has great compositional beauty. Buddy’s feet (enlarged in the perspective shown) take central position but the values he stands on is that pair of grandparents here as absurdly and maybe surreally normal, banal (to exhaust Bradshaw’s terms) and lovingly loved as persons could be. I do not know if this response, which may be as sentimental as some suspect the whole film to be, has much to do with the fact that I view as the child of a working class family in which grandparents figured largely. The People’s Friend, clutched throughout by Granny as here, seems to be taken from my experience as well.

And much of my experience was formed of such recognitions but I wonder if this true of others too. For instance, the lace antimacassar on the sofa seems to be the one owned by my parents in their council house. I felt the mass production (Woolworth’s?) tea service with the bizarre pattern to be the same as my parents had too. This is to say nothing of the wallpapers of the late 1960s. If anything this film reinvents family – and is the heteronormative family as I have already insisted, from which anything queer turns away for it has no relevance to this mythic world and its idealised beauty and consistency. And this is so because family straddles across swathes of time represented literally by generations (the roots of procreation and supposedly secure nurturing of the product of that procreation). This is not – maybe it does not need saying – any more real world either socially or psychosocially than the representation of the ‘Troubles’. It fails to see the hidden abuse at the root of some families and the diversities which actuate how family differences are delivered in the real world – in 1969 as much as now. It oversimplifies gender even because, although there are strong women, their virtues are ideologically gender feminised ones – a strength in coping, caring and waiting. Hence the turning into an icon of young Catherine who will be in Belfast when (or if) Buddy returns. Yet this myth is a potent one and subsists without truth in its realisation because it sometimes produces truths in some rare outcomes – especially those fortunate to succeed in an unequal and unfair society.

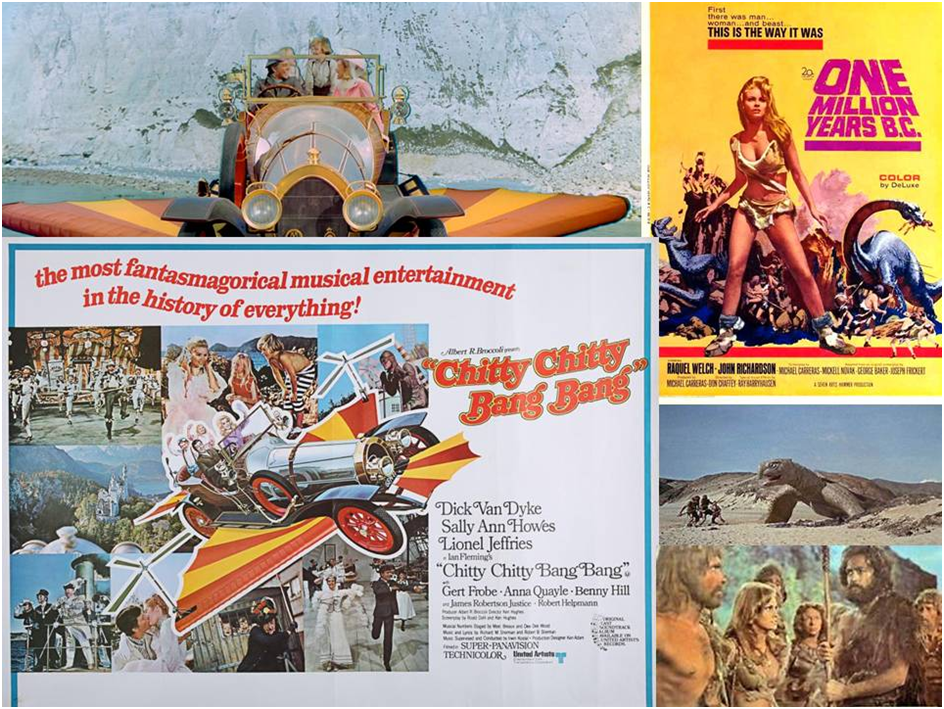

And we have to remember that Branagh makes this a film about watching, interpreting and desiring the benefits of popular theatrical and filmic art because he wants it (consciously or not) to predict his passionate eagerness to succeed in this arena and to attribute that to an origin not in itself cultured by art and aesthetics. Hence the switches into Technicolor as we watch a little of One Million Years BC and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

We learn how Buddy / Kenneth learns to see and respond communally to broad sweeps of emotion like that when Chitty flies off the edge of the cliffs at Dover and continues thus to fly, magicall over the white cliffs of Dover. This is an analogue of Branagh’s career and its take off. It explains why he wants from this work a ‘masterpiece’ as Newland suspected he did. Belfast is the evidence of the Bildungsroman of a great film director and even explains why the recreation of A Christmas Carol in the theatre, with Tom Wilkinson as Jacob Marley fits in with the sense of a divided career coming together.

We know, in relation to this film what Newland means when she says: ‘If Belfast had been rolled round in the dirt and broken glass, it might have made for a more powerful experience’. But, in the end, she asks for an experience that is irrelevant to the artistic project a film like Belfast represents. I do not see it as bearing Branagh’s ‘earnest feelings about his own past’ as if it were a burden which distorts the film. Instead, these feelings are its drivers and its topic, and the film tests whether we accept them as substantial and weighty enough to be a common possession – of growing boys at least. I am inclined to say they are. It was powerful for me not just because it succeeded in jerking tears from me but because these tears were made legible in the showing of a powerful myth, just as Shakespeare makes substantial and weighty myths about redemption (another myth in which I don’t believe but still need to understand myself if I am to make sense of human or animal relationships) in his late plays, especially The Winter’s Tale, and perhaps especially again in Branagh’s theatrical version of that play.

Indeed I will see this film again certain that this will enrich not impoverish it as an artistic and humane experience. Certain truths belong to things which cannot be articulated in statements with which we agree or disagree: they are fundamental premises like those used to ground many philosophical positions on the self. Call me old-fashioned. I believe that. So please see Belfast.

All the best

Steve

[1] Christina Newland (2022) ‘Tearjerker sweeps away reality of Troubles’ in i (21 January 2022).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Peter Bradshaw ‘Kenneth Branagh’s tender Troubles’ in The Guardian (21 January 2022). Page 12.

One thought on “Even if we accept that art owes a debt to truth, what kind of truths must it tell and / or show in order to be great art? Steve reflects on this in the case of cinema films that wear their search for excellence of a kind on their sleeves. The reflection happens around a case study of Kenneth Branagh’s ‘Belfast’ (based on seeing it for the first time on 21st January 2022 at the Odeon, Durham and two reviews). ”