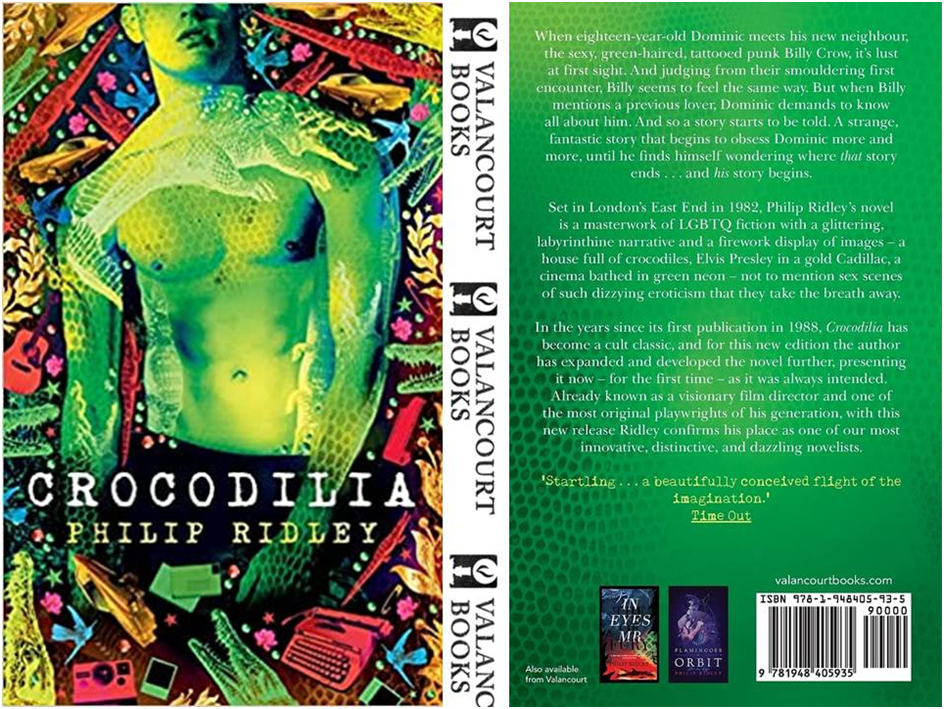

‘… stories are at the heart of it … the stories we tell to create ourselves… the stories we tell to create others. … And, of course, the stories we tell to fall in love’.[1] This is a blog reflecting on the role of story-telling in queer fiction and why a ‘story about crocodiles’ might be an appropriate vehicle for such reflections. It is based on Philip Ridley’s 2021 revision of his novel Crocodilia (first published in 1988) by Valancourt Books (Richmond, Virginia, USA).

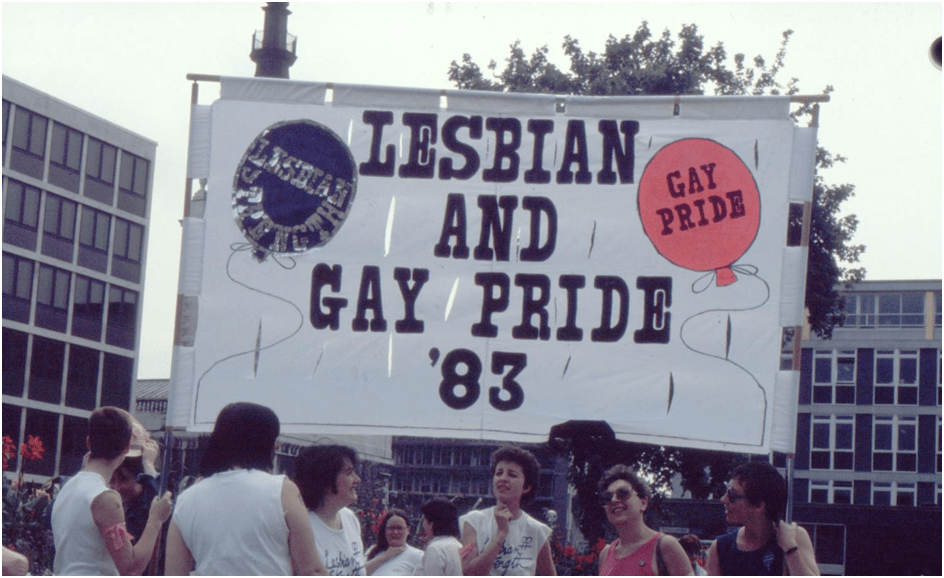

This blog is not an assessment of Crocodilia but rather an appreciation of the themes within it that make it appropriate to the times in which it was written and revised. If the original novel of 1988 appears to be aimed at the situation of marginalised queer people whose invisibility denied us a public history and set of expectations about how our fantasies based on our desire for other persons, whether a relationship, or even mere sexual encounter, lacked a public script or set of potential narrative models. Interviewed at the end of the novel Ridley describes the 1980s as a period in which ‘the LBGTQ community was being persecuted constantly’; not least by an ‘open and virulently homophobic’ government led by Margaret Thatcher. The aim of the original novel was to address then the lack of a ‘real representation of LGBTQ people’ which would provide role models of what queer relationships could be like – how they might start and develop for instance.[2] The revision of the novel for the current edition is much more aimed at refining the stylistic and technical means of the novel as a literary genre or combination of genres that aim to provide public stories.

Strangely enough one effect of this greater transparency about the means of story-telling will make it more clear to readers that the mere existence of public stories about LGBTQ relationships did not guarantee that these stories were any more real as representations, even though they provided models and scripts of relationship and sex that were positive about sex with people of the same sex/gender, that we had lacked, just as the existence of the story of Romeo and Juliet does not the reality of heterosexual sex; a point actually made by Ridley in the interview at the conclusion of the novel.[3] Indeed the crux of the novel is that the relationship of fantasy and reality in stories intersects with the relationship, equally complex perhaps, as that between lies and truths, without asserting that fantasy does not contain truths and moreover that what we call ‘reality’ contains even more lies.

The central fantasy conceit is that concerning the representation of crocodiles may contain much that is unreal but that it might also be a way of more easily avoiding lies that have become engrained in the habitual forms of a heteronormative society. Hence Billy’s claim that, despite the evidence of fabrication in his story, “I haven’t been lying to you at all. All I’ve done is tell you something that’s … unreal.”[4] And when the real of everyday life is full of lies – like the lies told by Dominic’s mother that hide a truth which should have acknowledged the queer life of both Major Vernon, the bisexual manager of the Rex cinema that employed her, and Dirk Bogarde. Despite the fact that both persons in some different way passed as heterosexual, and that one (far from being a fictional or unreal character as Major Vernon definitely is) was actually a real man living a necessary lie in a homophobic society. Both then illustrate the way in which a lie is the condition of some kinds of pretended reality and the necessity of a fantasy life.[5]

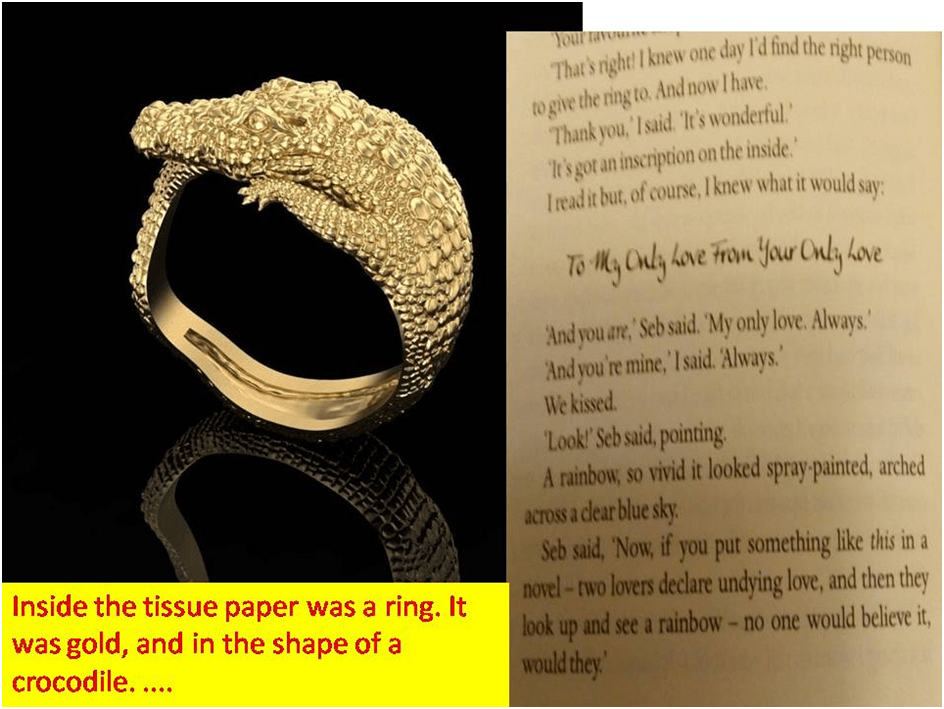

The crocodile is an animal oft represented by misleading stereotypes. In Disney’s Peter Pan for instance, which appears so significantly in very different strands of this novel’s narratives, matters because the transformation of a thing he considers ‘SACRED’ leads the crocodile encrusted life of Kalvin (the original artist of Billy Crow’s later completion of a crocodile mythology) to a premature end. It is a representation that has become no more than AN INSULT! A TRAVESTY!’ And so was the representation of queer lives. Billy only exists in the novel to measure out the time it takes Dominic to learn that he might find a real relationship from a fantasy – that with Seb, though the fantasy is in part to turn out to be an untruth. Dom will not love Seb for ever and vice versa but that does not query the beauty of their story together any more that does the untimely death of star-cross’d lovers, Romeo and Juliet.

Did we stay as much in love as we were during that heatwave of 1982? Of course we didn’t. … Seb met someone else … and I would have been heartbroken were it not for the fact that I’d already met someone else too, …[6]

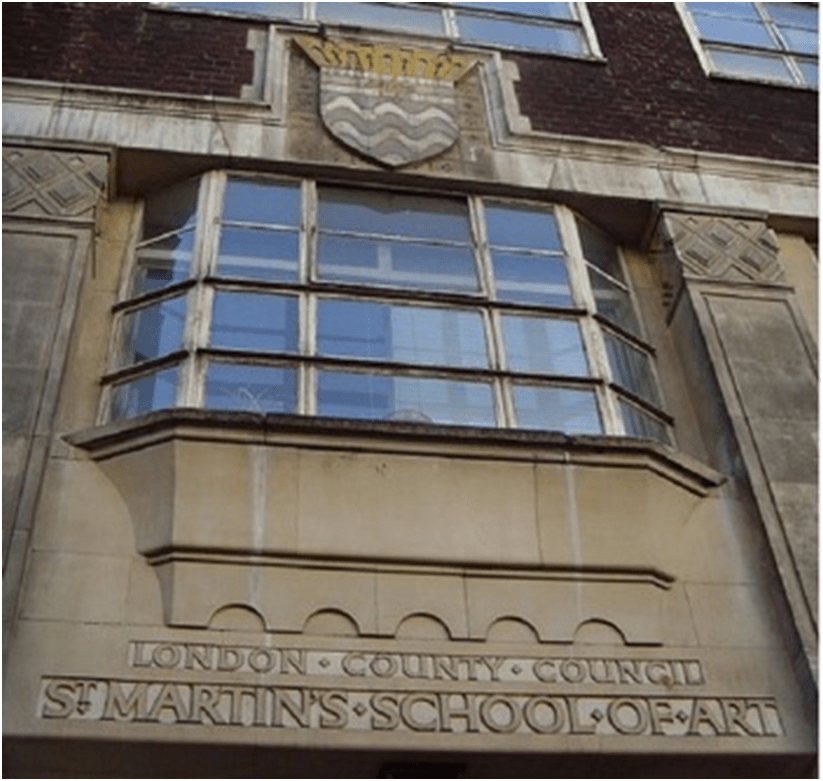

The locus of tragedy is the character of Billy Crow. Billy had, Ridley tells us, an analogue in a person he knew at St. Martin’s College of Art, the art school around which so much of the novel’s mock histories and character expectations revolve, but this analogue was only an analogue not a model for Billy Crow. Their closeness included sharing images deriving from the other on the surface of their bodies. And it ‘was his painting that excited me most’.[7] That ‘real’ person fed into the novel, Ridley hints, mainly because of the quality of his art and its similarity to his own. Even his name ‘crow’ comes from an image in Ridley’s own artwork, including ‘a charcoal drawing called Corvum Cum’: ‘It was of a man ejaculating a Crow’.[8] The association of Billy with a ‘fantastic’ (in the original sense of the word), exciting and driven artistry and ejaculate (this novel is sticky with cum) associates Billy with the processes driving artistic invention and in this novel such invention is not only the imagination (the creation of visual images let’s say) but their embellishment in stories of high fantasy and heightened expectation of a coming event. For Billy Crow is surely the William (the formal name that is familiarised as Billy) Corvus (the Latin for Crow) who provides the novel’s epigram: ‘Sex and stories are very similar: they both require feeling and a climax’.[9] It is probable that Ted Hughes was in Ridley’s mind because of the enormous effect of his 1970 work Crow, which created a mythology around that animal. In a lesser sense, perhaps, Ridley does something similar with his own fascination with the crocodile, although without the intensity of Hughes guilt about the past.

For Ted Hughes Crow was a project larger than its achieved form, as Neil Roberts, for the Ted Hughes Society, tells us.[10] Billy Crow does finish the visual masterpiece started by Kalvin on crocodiles for which he was selected by the brothers / doubles Trystan and Theo. Indeed the expectation of Billy finishing his work seems to set the pressure and drive on the narrative time of this novel (‘Has he finished the hallway?’[11]) and to mark its ending, as Billy reads its making as an imaginative journey which released Dom to Seb’s enjoy the latter ‘in the sexy white chinos’ in the novel’s final chapter (before though Dom’s epilogue)..

“Are you … are you leaving?”

“Yes. Everything I needed to do here … it’s all done.”

He took a step towards me. “We have been on quite a journey, haven’t we?”

“… Yeah.”

“And now you are on another journey. With Seb in the sexy white chinos. …”.[12]

The plot of this novel is in fact I believe a kind of psychological working through of the crocodile project to such an end to test the role of visual fantasy and creatively fantastic fiction in making sense of the lives of people denied a model for their future relationships. It matches the three types of story which swim, under the surface of the Dom’s story so we can’t, like crocodiles, see them rising, associated with Billy Crow, but which all may (including Billy Crow himself) be figments of Dom’s imagination like the fairy story of the crocodile (in Gothic calligraphy) he first made up, he tells Seb but only near the novel’s end, when ‘I was fourteen’.[13] That story is about how a king falls in love with something he barely knows how to countenance – a Crocodile God. The other stories where love is mediated through accidents of similarity (between Theo and Trystan – so unlike the ‘real’ brothers Rory and Seb in the novel) that tell fantastic tales of the role of sameness in love, in order to make sense of same-sex encounters in a world that accommodates only different sex encounters (and that in a way that oversimplifies differences between people).

For one of the beauties of this novel about stories and storytellers (which ends with a long ‘storytelling-fugue’),[14] wherein the boundaries between stories are both clear and then not – hence the musical analogy is that nearly everyone tells stories that might be lies. Darryl is a storyteller whose narratives aim to cover up lifelong experiences of loss – of parents, looks and an ideal role as a model. Dom’s Mum too tells stories about princesses that mask her disappointments in life, especially sexually romantic ones in which a garden ‘blossomed with love letters’ (as indeed does the garden Dom lives with as well as with sister Anne – letters placed by Billy Crow).

However, Mum’s stories with ‘real’ people, like Darryl’s, also shade into both fiction and lies. Zoë contradicts those stories of Mum’s which justified her distance from her daughter. Her major fictional story about securing a major coup for the Rex cinema in the form of a premiere for Doctor in the Slums with Dirk Bogarde in her cinema is at the crux we will find of Dom’s story and its meanings (since Dirk decided on this only after having sex with Major Vernon). Only after the experience of a real ending in her own life story – her husband’s death – does she abandon fairy stories however. She still tells stories of ‘real’ people that create an ‘unreal version of my dad’s life’ but these stories, Dom says, actually ‘felt more truthful than what happened’ now.[15]

That the novel was in part aimed at making young gay men feel not only that they were not alone in the world as Ridley (and I) did as queer children may explain why the sex in it is so uncomplicated and oversimplified, especially the introductions between gay men. It never was thus I believe. But once Dom learns some potential sexual methodologies – though largely confined to oral and finger exercises – he will learn that the journey with Seb and the acceptance from him of a crocodile ring which appears like a motif throughout the novel’s encounters does not guarantee embedded narrative assumptions of its legend: wherein lovers pledge exclusivity and temporal duration:

This scene follows the information in the novel’s Epilogue that has already told us that Seb and Dom’s relationship was short-lived and ended, though without acrimony. In a sense this illustrates the fact that though fictions form part of our lives and are necessary for us, including those that tell of imaginatively authorised (in literature and art) unending love, but that they fictions can contain things that do not guarantee a lived truth except in that place of imagination where magic remains necessary – our emotional lives. The novel also tells us that perhaps we can only survive when we realise love is a story and that stories end like lives. Hence the need to come to terms with a death in each section of the novel. But that unbelievable things lie in fiction does not mean we are right to call these thing LIES!

For me, this novel, though not a great literary work, does much of the important work good literature does. And it is readable. It is also full of earnestness about the importance of supplying stories of queer lives that take those lives seriously. Do read it. Stories change us. And as Billy sings into the receptive ear of Dom who does not know how to ‘find myself’ (ibid: 13) Billy is a source of storied metamorphosis:

“I am the change you want to be” (ibid: 20)

All the best

Steve

[1] Philip Ridley (2021: 288) Crocodilia Richmond, Virginia, USA, Valancourt Books. This quotation from author interview ‘The Stories We Tell’ pp. 276 – 288.

[2] Ibid: 282f.

[3] Ibid: 283

[4] Ibid: 266

[5] Ibid: 206

[6] Ibid: 273

[7] Ibid: 272f.

[8] Ibid: 280f.

[9] Ibid: 5

[10]Neil Roberts (2022) ‘Neil Roberts introduces Ted Hughes’s ‘masterpiece’. Available at: Crow — The Ted Hughes Society

[11] Ridley op.cit.: 84

[12] Ibid: 267

[13] Ibid: 226

[14] Ibid: 288.

[15] Ibid: 272f.