Reflecting on an exhibition I had not expected to enjoy so much. It was at York Art Gallery, entitled Young Gainsborough: Rediscovered Landscape Drawings (based on a visit to it on the 15th January 2022).

Visiting any city as Omicron sweeps over us with our ignorance of it as deep as that of a directionless government in mid-January might seem a lost cause even only as a day trip from Crook in County Durham, so for this january visit we ensured much to do. The schedule was a visit to the Brishish Provincial Book Fair Association New Year festival of second hand and antiquarian book sales at the Race-Course, lunch at a favoured Indian Restaurant with a dear friend and an exhibition at the York Art Gallery, this one primarily of newly discovered drawings and sketches by Thomas Gainsborough. These drawings can be described as newly found (in fact in the royal collection at Windsor in 2017 as we shall see) because previously contained in a folder attributing them, wrongly, to Edwin Landseer (though I doubt even a rank amateur like me would mistake the animals in these drawings for Landseer’s). I was rather wary of the latter experience, since, though I am stunned often when I see any individual Gainsborough work, I have not warmed to him emotionally – and unfortunately that matters to me.

Nevertheless through the mistiest and coldest of days (it was probably much warmer than average Januaries) York’s architecture and street designs were putting on a gaudy show akin to the lights in the twigs of bare trees, the Bookfair was fun and dinner with young friend and physicist (daughter of friends near home but at university in York), Eleanor, more than pleasing.

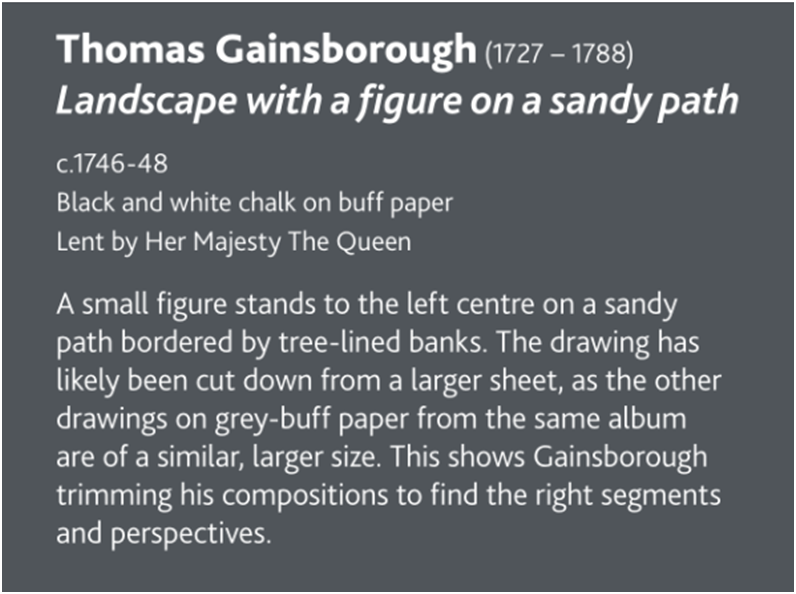

So on to the exhibition we went. The Exhibition related primarily to the 26 or so drawings found in the Royal Collection at Windsor in 2017, the story of which can be read at leisure in a report by Dalya Alberge in an article in The Guardian of that year.[1] Described correctly by Alberge in 2017 as ‘black-and-white chalk drawings – vivid depictions of landscapes around Sudbury, Gainsborough’s birthplace in Suffolk – have never been published or exhibited before’, even that last fact hardly stirs the blood of the mere viewer of art looking for a way into a tradition outside their experience. They were discovered in time to receive report in the latest Gainsborough biography by James Hamilton, Gainsborough: A Portrait, published also in that year and which I read. To Hamilton these drawings supported his own reading of the artist as “most inquisitive and energetic”.[2] But even this biography, with its intriguing and relevant readings hardly captured me for Gainsborough, although a latent liking has always drawn me to read more about him.

Indeed what York curators have leapt upon is not a modish approach to the innovation that led to us seeing Gainsborough as at the beginning of a new tradition of landscape painting, which is indeed how a later Suffolk artist and admirer, John Constable, saw him.[3] This tradition originated in Gainsborough’s blending, they claim, of direct observation of material directly from nature, drawn en plein air as it were, and the artifice of studio composition that meant his landscapes were necessarily manipulated to form coherent designs as painting – were, as we might say, compositional wholes.

Gainsborough would later create imaginary landscapes using broccoli, moss and stones on his table. These drawings “do prove how much firmly rooted he was in the study of nature”, [the art historian, Lindsay Stainton] said. “It underlines his very serious approach to landscape, which is quite novel in British art at this time. We are looking at quite an early phase in our landscape history.”’[4]

None of these are new observations about Gainsborough. Nicola Kalinky in her 1995 contribution to the Phaidon Guides cites the source of this knowledge in the great eighteenth century painter and Royal Academician Joshua Reynolds and Uvedale Price, a master of the Picturesque in landscape. She interprets this evidence as a part of his ‘rapid exploitation of chance effects, such as “moppings”, where applied colour with sponges to indicate the general masses of landscape’.[5] She notes, perhaps with less emphasis than in this exhibition because of the detail of the preparatory sketches discovered in 2017 which include undeniable evidence of drawing from direct observation, Gainsborough’s outings in the West Country with Ozias Humphrey into the ‘circumjacent Scenery’.[6]

The curators here however were so excited by that apparent paradox that they devote a room at the end of the exhibition to records of a project with teenage school children modelling imaginary vista from the same materials as Gainsborough, especially broccoli, and using them as art or as the basis for a later transformation into another medium.

Working with them were professional artists including Jade Montserrat, and she too was commissioned to make works based on this principles of manipulation of the stuff of nature, psychology, and human/animal physiology including her own body incarcerated in mud or buried in banks or trenches found in external natural scenes. This method of contemporary continuation of artistic experiment from the past is used a lot by York’s very exciting exhibitions these days. My record of still photographs barely covers the excitement of Montserrat’s ability to make Gainsborough exciting again, as she did for the primary children too – although by video link.

It is a method of curation Gainsborough’s House also attempted by exploring how and why the modern figurative artist, John Bellany, valued Gainsborough precisely because such experiments in observation and design lead to what, at ‘the end of the day it is all about’, which is ‘the intensity of vision’ of an artist.[7] And this characteristic matters because even the driest of academic accounts of Gainsborough emphasise quite rightly his ethical vision of the world that enables humans to see that their place in the world is one accountable to values that make us human rather than just powerful and rich. And this despite the fact that some of Gainsborough’s most exquisite portraits are of the powerful and rich. It is an ethical vision that long ago John Berger identified in the figures and landscapes of this painter in Ways of Seeing (see the video linked here of the relevant part of the BBC series). We do not have to agree with Berger’s socialist analysis (though I do) to see this ethical weight in his work that closely examined the things he saw in terms of social relations, for these were built into the position of the painter as a relatively powerless ‘servant’ of the rich and powerful.

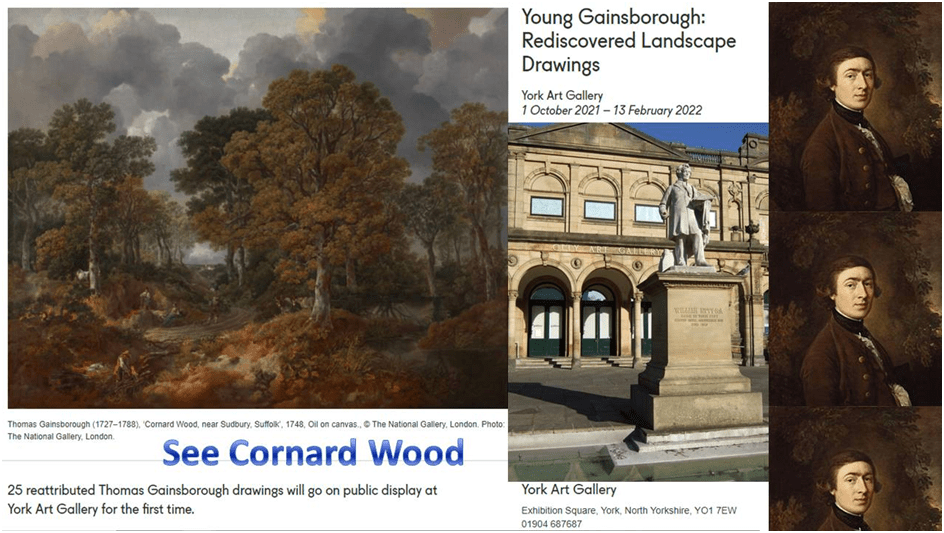

His vision was very ably, if dryly, examined, looking at a number of factors by Amal Asfour and Paul Williamson as early as 1999.[8] One is a common culture with the radical Dutch society of his predecessor artists in landscape like Ruisdael (in show at this exhibition). This culture is not only in the humanist and individualistic but also suffused with the earnest Protestant morality of a new emergent class who felt that in Holland they had overthrown the shackles of an over-mighty aristocracy. This the authors find in the famed painting once known as The Forest of Cornard Wood, which invoked an ethically ordered nature:

… the picture shows a natural order involving church, sky, earth, man, woman, and animal and the diverse elements achieve a thematic unity which is mirrored in the composition … suggestive of a religious subculture.[9]

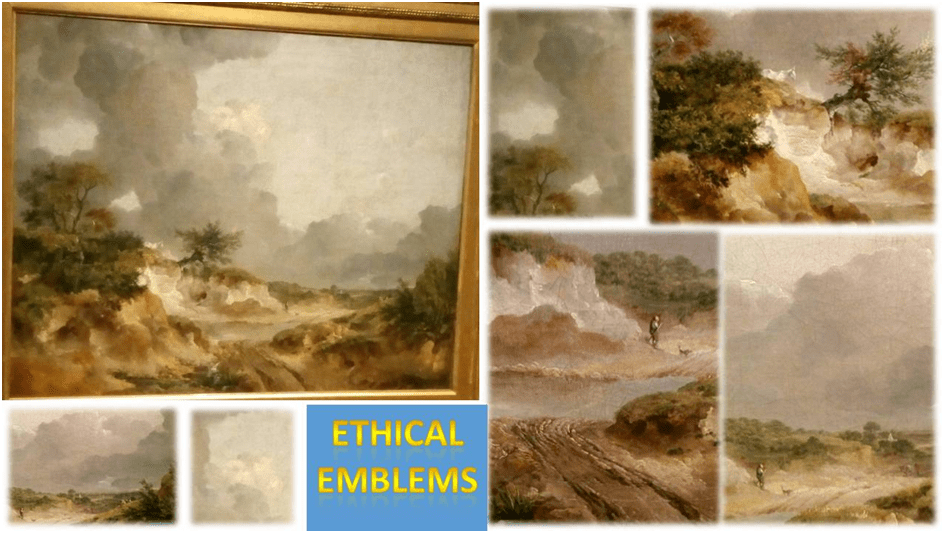

Collage of my photographs of the following. Below is a print screen of the file of captions from the exhibition available at the York Gallery website.

What we see here is a highly determined view of the common demographic base of a society in a common land (already threatened by enclosure) populated by common types and activities with animals that shared their owner’s lowly lives. But the central focus is the distant community and its very visible church. Indeed Asfour and Williamson say the traditional role of the forest as a symbol of confusion and moral disorder (as in Midsummer Night’s Dream) is paradoxically put in the ‘background’ ethically by a distant but clear view of (or indeed ‘a point of focus’ on) the church, to which a path wends its pilgrimage.[10] But I think, and will go on to explore further that these authors interpret these design features in the creation a whole painting in far too politically and perhaps religiously a conservative way, in precisely the way John Berger was questioning.

To explore this we need to look at another factor in Gainsborough’s learning in matters of social ethics that emerges from his being a dependent ‘service-provider’ (in some senses treated as a mere merchant of specialist goods) for aristocratic patrons whom he could not respect but must obey, which James Hamilton also pointed to in his recent biography, I seem to remember. Gainsborough sometimes expressed this in his hatred of being tied to the genre of the society portrait, where his deeper preference was for, as he called it, ‘Landskip’. Here this in a letter of Gainsborough’s (eighteenth century spelling standards are maintained):

… we must jogg on and be content with the jingling of the Bells, only d_mn it I hate a dust, the kicking up of a dust and being confined In Harness to follow the track, whilst others ride in the waggon, under cover, stretching their Legs in the straw at Ease, and gazing at Green Trees & Blue skies without half my Taste, that’s damn’d hard.

That Gainsborough projects his feelings and situation into the situation of a pack animal pulling a drover’s cart is no accident. His letter expresses in a pastoral conceit his desire to ‘paint Landskips’ as a means of escaping powerful persons, especially (since his sexism cannot be avoided) powerful women: ‘fine ladies and their Tea drinkings, Dancings, Husband huntings and such’.[11] Pastoral of course, as Asfour and Williamson remind us by citing Frank Kermode (then the major figure in British literary criticism), is primarily ‘an urban product’.[12] The model is one inherited from the culture of Greece and Rome and especially the Georgics of Virgil but imported into British culture by Spenser and Milton amongst others as a means of articulating a revolt against the ‘luxurious and demoralised city-dweller’, court or government. The habit of critiquing power, wealth and status at the higher levels of hierarchies often went as far as investing the values involved in a return to nature and an agrarian economy in the lives of animals.

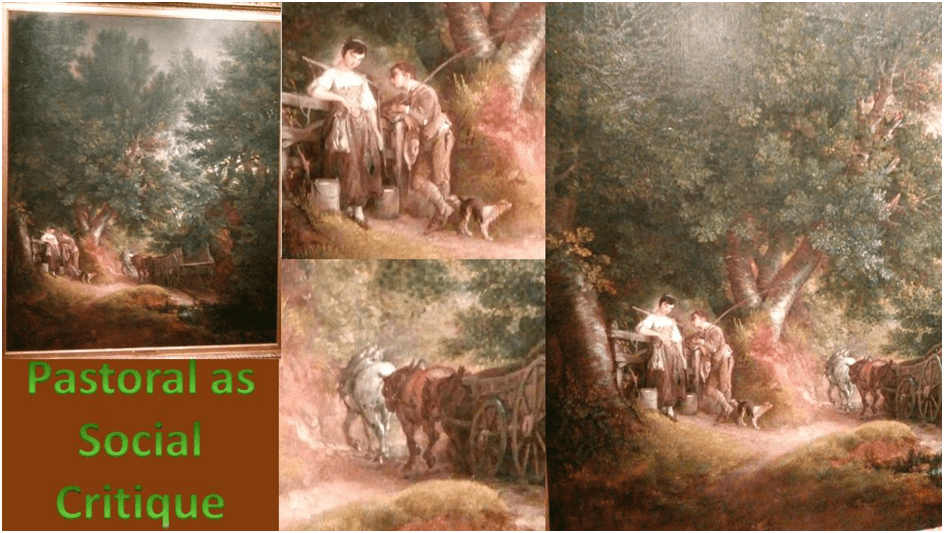

This is the moment captured in Gainsborough’s conceit of himself as a pack animal In Harness. Those subjugated to the power of those who ought to be in control and drive progress can see that they are left to plod, supposedly entertained by an art also produced by their labour not of the city, court or government, whatever the august intentions of those failed ‘leaders’ sounds. Quoting this as Asfour and Williamson do, ought perhaps to have alerted those authors to the fact that badly or even well governed pack animals are a considerable feature of Gainsborough’s peopled landscapes and that perhaps ought to be noted as a handle to the interpretation of his landscape art. Yet this they do not do. An obvious opportunity occurs in their treatment of the 1766 painting Wooded Landscape with Country Wagon, Milkmaid and Drover, which is also on show in this exhibition. It can virtually be decoded by Gainsborough’s letter above (although Asfour and Williamson use that letter elsewhere in the same chapter and without full cognisance of significance within it). Here is the painting with some significant detail selected for clearer view:

A collage of painting and detail of 1766 painting Wooded Landscape with Country Wagon, Milkmaid and Drover. Below the label from the exhibition.

It is clear even from the label that models of gendered behaviour in courtship are an ethical target here: the Milkmaid is marked as immodest, even if only by virtue of a too clear thrusting forward of her hips and a contraposto style of attracting attention to her body. The Drover is less at fault it would seem in this model because his fascination is seen as called forth rather than thrust upon its object, but the failing of the drover is clear to the more intelligent of the animals in the scene starting with the Drover’s dog, who sees the danger involved in that the unattended cart is still being pulled forward by the shire horses at the front of the team of pack animals. The capture of stilled motion here is remarkable, not least because towards the back of the tem, a donkey looking towards the drover and his dog knows that it too will soon be engaged in pulling (or be crushed by the cart) as the horses advance. The supposedly governed animals critique the drover as the kind of governance they lack. Thence if the attack on immodesty falls on the milkmaid failing to be ‘natural’ in her femininity, the attack on lack of due governance and control is turned on the male drover alone.

Donkeys often paradoxically (given their reputation for stupidity) become icons of failings in the human realm and this is why I believe their faces are so often anthropomorphised in Gainsborough drawings seen in this collection. They are an ideal means of showing how the easily led can sometimes have more sense of direction than those put in a position to give direction. And thus the lesson expands into civil politics. As Boris Johnson’s behaviour continually reminds us this is not just a matter of importance in eighteenth century politics. Asfour and Williamson are, on the other hand, so obsessed by seeing a false (in my view) distinction between designed against observed landscapes (where Cornard Wood with its distant vistas like those in Ruisdael is an example) contrasts with the enclosure emphasised in this scene. In my view their reading under-estimates the focused and intelligent approach to allegoric scenes representing different themes ways used by Gainsborough in each painting. In the 1776 scene, the enclosure and ascending path that cup the scene, as well as the ‘dissolution of the distance into light’ have a distinct meaning in creating moral emblems of the drover’s enclosed foresight and the entrapment of the horses and other animals in a scenario not of their making but whose consequences they will bear. The metaphors here are the same as in Gainsborough’s letter. Lets remind ourselves of the difference of The Cornard Wood painting.

Here a distant vista of the church does not tend to open the view for anyone in the painting but only for the tasteful view of the artist and educated viewer. The importance of the various scenarios that overpopulate the common ground of the forest is that each figure has its back turned to that vista and is locked in an enclosure of its own. The key example is the sand quarry or pit being dug by the male that has brought his vision so low, even if his back were not turned, he could not see the view. The red coat or cloak seems to bleed from the fissure with which he wounds the earth and ought perhaps to be a moral warning to the young woman with whom he passes the time. The only face overtly pointed towards the viewer and bringing attention to human folly is a donkey tethered by the winding path whose rout to the town of Sudbury is obscured.

Humans so often fail to equate their wishes with what is simple and not over-refined. That is so often a message of pastoral and it applies to the domains of the political, social, and aesthetic worlds. In this sense it is so true that, as the authors we are dealing with say of Gainsborough’s natural landscapes: ‘the sensuous impulse is balanced by more sombre symbolic overtones’.[13]

But before doing so we might examine another painting in the exhibition (partly because I love it so and especially its white donkey supervising the whole) which is A View in Suffolk (1727 – 1788). Here is a collage of painting, detail there from and the label from the exhibition.

I would say with Asfour and Williamson that in Gainsborough the effects traced to artistic influence here are not only symbolic but allegoric since they fit a continuous story that extends from the stilled moment of the pictures. The visual memes of these allegories are the same as those in seventeenth century protestant allegory: roads which ascend or descend with concomitant levels of difficult, obscure or clear vistas and prospects (of a future or redemption), darkness, light and shadow and open or closed settings to name but a few. Yet the label here makes the same points as did Kalinsky in 1995 when she identified this painting with another name and date (Landscape with Sandpit 1746-7). She says that Gainsborough ‘finds his subject in the constant movement and life of nature, suggested by the scudding clouds, windswept scrub and fitful patterns of light and shade’. Whilst this aligns with later Romantic painters and poets, it drains nature of the meanings the eighteenth century was inclined to give to notions of the natural and civil, including fear of the wild and disorderly. And we how darkness and descending paths are contrasted with clear light and ascending paths in many of the drawings that the exhibitions treats largely as study exercises based on imitation of Wijnants or Ruisdael or copies from the reality of Suffolk scenes alone. Yet there are other reasons why designing compositional wholes might want to combine imaginative modelling and detailed observation from nature.

The patterns of dark and shade in this scene are created by design, cognitions as well as for sense effects – wild nature aligns with towering stormy clouds and light breaks through over a distant human settlement. The road with its winds, ascent and descents bears the ruts of constant use and warns of danger to those who do not guide their wagons with care through the build up of water on the sandy surface of the pit. The lone white donkey makes us doubly aware of the way in which careless work on the pit has created unsafe fissures in the ground and holes that might absorb us. The cliff face has been so dug into that the overhang on its edge is perilous.

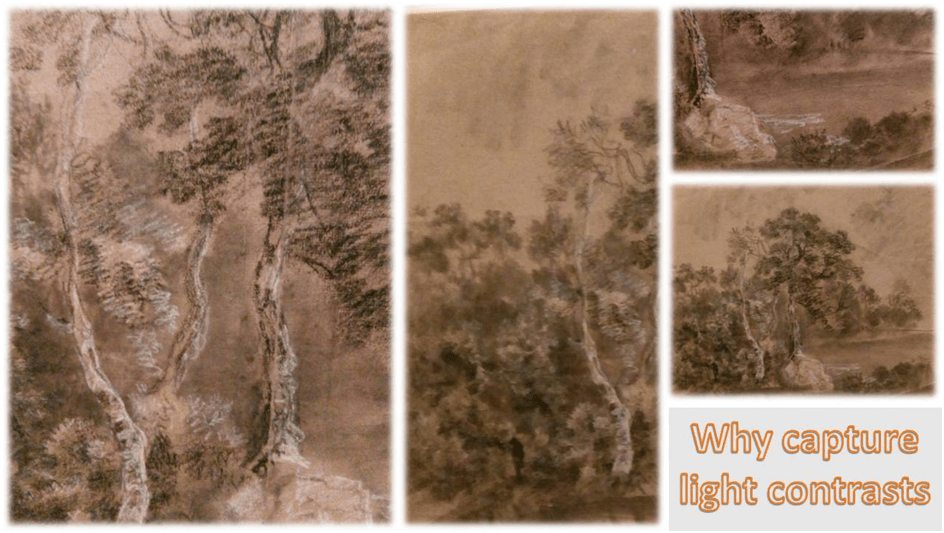

This then is a good moment to dive into what more we learn from the new drawings exhibited. In these drawings Gainsborough appears to be working on both capturing observational material, especially in details, planning coherent designs for either cognitive or aesthetic reasons and practising technique in the capture of contrasts of mass and light and shade. Although aesthetic issues are stressed in the exhibition labels all of these matters are even more important when the place and definition of a road vis-a-vis surrounding landscape feed into allegoric or emblematic meaning. The reason for this is hinted at when Gainsborough discusses in about 1763 his artistic method using a rather open question rather than a statement.

‘… do you really think that a regular Composition in the Landskip way should ever be fill’d with History, or any figures, but such as fill a place (I won’t say stop a Gap) or to create a little business for the Eye to be drawn from the Trees in order to return to them with more glee’.[14]

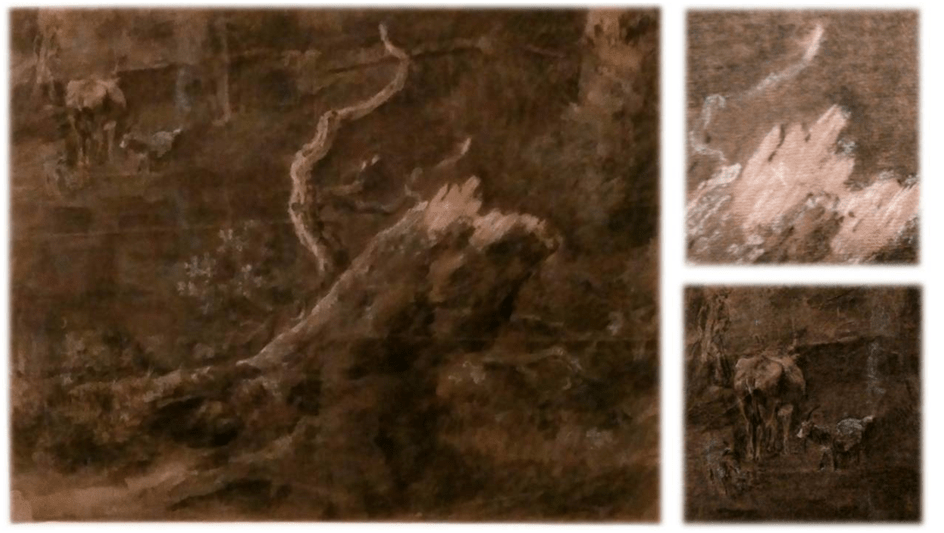

The answer to this question is not as obvious as it seems. It appears that Gainsborough is stressing the importance of the natural elements of landscape over the use of figures and narratives (History genre painting). But this need not be the case, especially given the rarity of compositions with at least one figure in the oeuvre. For the return of the eye from the overly sophisticated concerns of the human and the social story divorced from other considerations such as a regard for the unrefined truths of religion and nature. This it is still an ethical position to demand that human eyes consider themselves within a picture only to return to nature and truth with more glee. Given this view, we would expect drawings to examine how a recognisable natural object could be both recognisable and meaningful in the context of a comprehensive design of the whole picture. That a recognisable observed object look to be in its place however need not mean that mimetic capture of a ‘real’ object in a real place is the aim of painting. Far from it! And this is indeed what I felt I saw. Moreover, the techniques practised in the drawings need to show how contrasts of light and dark can be designed within the whole to be both meaningful ethically and recognisable as ‘natural’. Let us look at a sketch that the exhibition recognises as capturing at least one object from observed nature. In the first it is the stump of a decayed tree (the label precedes the collage of the drawing and two details).

The label describes the unusual method of this drawing beautifully but as if the main purpose were mimetic rather than to engineer meanings and ideas. The contrast of the bare buff paper with tonal variations of black chalk however feed into the association of death and decay in this picture against the invented background composition of well placed animals. In building a ‘stock of motifs’ is Gainsborough serving the imaginary or manipulated landscape wholes he could create as an artist or finding motifs for meanings that painting might convey to be read as one reads God’s message in an emblematic world, contrasting fallen magnificence and simplicity for instance – a reminder needed by many of the subjects of his wonderful portraits.

If we consider this drawing again the label sees its purpose as primarily technical – an exercise in perspective in part, but for me the radical use of contrasting black and white chalk seems designed as well to understand how light and dark relate to the moody reflection of the very small figure on the ‘sandy path’. The translation of the foliage into chalk marks (not just hatching since we see hear the movement of the hand making the marks in contrasting densities and volumes of light effect intended) is remarkable. It is like an attempt to capture life in death thematically in blobs of dark and shade. This is perhaps even more so in the following example, though I could never convince someone who did not see these effects being practises – a kind of Paysage Moralisé that art history no longer countenances.

All the best

Steve

[1]Dalya Alberge (2017) ‘Thomas Gainsborough sketches newly discovered at Windsor Castle’ in The Guardian (Sun 9 Jul 2017 12.33 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2017/jul/09/thomas-gainsborough-sketches-newly-discovered-at-windsor-castle

[2] Cited ibid.

[3] Constable said ‘I see Gainborough in every hedge and hollow tree’ of their common childhood rural origins in Suffolk. Cited Diane Perkins (2008: 10) ‘John Bellany and Thomas Gainsborough: The Painters Converse’ in D. Perkins & J. McKenzie (eds.) John Bellany and Thomas Gainsborough Sudbury, The Gainsborough’s House Society, 7 – 14.

[4] Stainton cited ibid.

[5] Nicola Kalinsky (1995: 21) Gainsborough London & New York, Phaidon Press.

[6] Ibid: 21

[7] Ibid: 11

[8] Amal Asfour and Paul Williamson (1999) Gainsborough’s Vision Liverpool, Liverpool University Press.

[9] Ibid: 26

[10] Ibid: 25

[11] Ibid: 182

[12] Ibid: 182

[13] Ibid: 174

[14] Quoted ibid: 32