This blog is based on my own belief that the writing of a queer ‘life’ (whether as biography or autobiography) is fraught with difficulties that are sometimes also experienced in living such lives. I test it by examining R. Tripp Evan’s 2010 book, Grant Wood: a Life New York, Alfred A. Knopf.

‘A Life’ is a wonderful term and it cannot only be applied to a piece of writing such as R. Tripp Evan’s biography of Grant Wood. Indeed I believe it is used in all its richness inside this biography to show that lives are articulated, sometimes in speech, sometimes in writing in ways in which both its content and form can vary massively – sometimes in matters of fact or interpretation or a mix of the two. And I was attracted to read the book precisely because of its take on a ‘life’ – that situated in twentieth-century North America where how people lived, the stories they told of themselves or were told about themselves about how they lived and the stilled or mobile pictures they made of that life in its process, sometimes in the form of art, were so fraught. All that is captured in The Power of the Dog (see my blog review at this link).

And I found the book because I take the wonderful queer literary review magazine The Gay and Lesbian Review (LGR), which featured a piece by Ignacio Darnaude that first made me seek and find this wonderful if now aged biography (use link for online paywalled version to Darnaude’s piece).[1] In 2010 when Tripp Evan’s book appeared my sexual politics were thinner (less concerned with the richness of the stories of individual and other differences that mark queer rather than ‘gay’ politics) than they have become with age if not maturity (heaven forbid I ever mature!). But wafer-thin is precisely what Darnaude’s interpretation of Wood is I believe and I need Tripp Evans as a corrective (most of the facts in Darnaude can be found in the earlier book, through the interpretations are richer in my opinion. Darnaude is, a footnote to his article tells us, working on a docuseries entitled Hiding in Plain Sight: Breaking the Code in Art. But the sense that gay identity is hidden by masked or coded behaviours, though easy to understand and in some sense useful to interpret some of the grosser aspects of our history lacks nuance when we look at how people live their lives regardless of any category. It can be only part of the story, though we shall see it too in Tripp Evan’s readings of some parts of some of his artworks, notably The Appraisal of 1931 (of which more later).

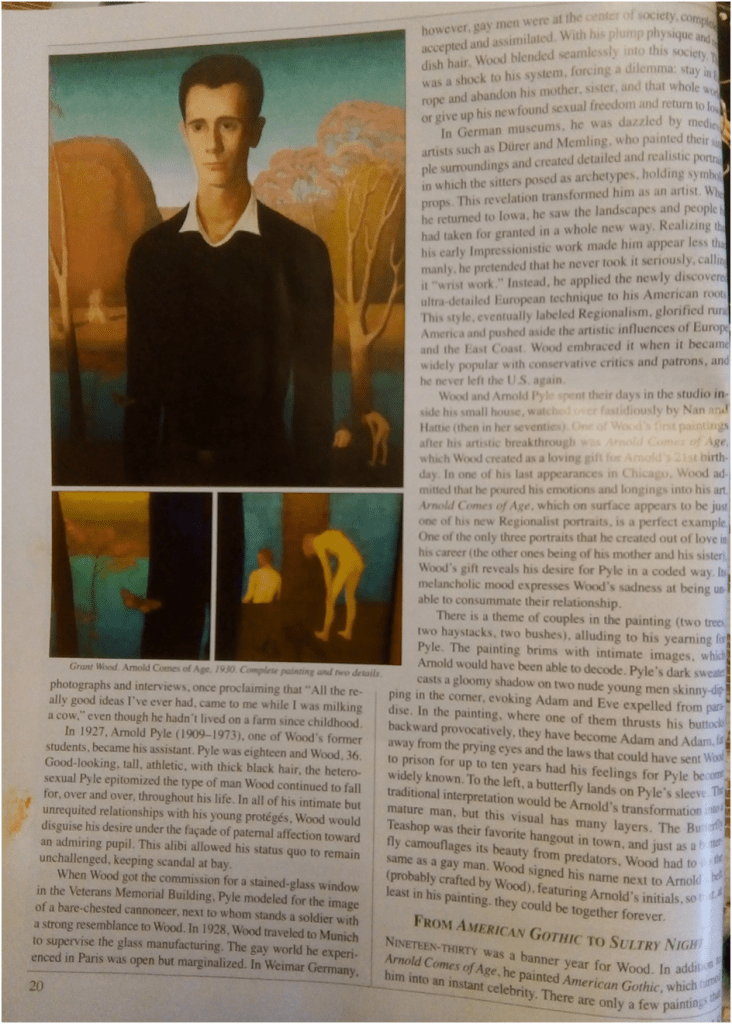

The idea that ‘being gay’ is a thing (a recognisable identity) we can either openly show or covertly hide has a major problem attached to it in my eyes: that is that it posits a kind of ontological category (a way of dividing what it means to have being as a person in the world between either gay and not gay), which assumes that appearing not gay in some way or other, when one just is gay in the final analysis, is a kind of pretence or role-play. This implies that there is, at some level, a more authentic way of being that defines someone who is gay, despite any appearance to the contrary or in playful nuance. I find this troublesome and this is why I reject the implications of Darnaude’s interpretation of Wood, and possibly others in his planned docuseries. For instance, here is Darnaude’s interpretation of the butterfly as an image of romantic love (they occur often in the paintings) in Arnold Comes of Age, painted for Arnold Pyle’s 21st birthday (Wood was some 18 years older and was Pyle’s tutor at college before he employed him as an assistant): ‘The Butterfly Teashop was their favourite hangout in town, and just as a butterfly camouflages its beauty from predators, Wood had to do the same as a gay man’.[2]

This treatment isn’t a million miles away from a much less sympathetic and empathetic one of how Wood manifests his identity in visual symbols in Robert Hughes’ notorious dismissal of the artist and man that was Grant Wood. Indeed, at one level of seeing things, these contrasting writers just display different tolerances to people who hide rather than share their sexual identity. Phenomena become little less than the mask of that sexual identity, if that is what is lying behind it, and different understandings of its necessity in social oppression or personal weakness. At best they are coded messages which mean, to cognoscenti, the same thing as our understanding of what sexual identity is. Hughes says, when discussing Wood as an example of a rural Regionalist school of painting:

…’, far from being a sturdy son of the soil, Wood was a timid and deeply closeted homosexual. …/…/ … Today, one is inclined to see’ [the painting, American Gothic] ‘like so much of Wood’s work, as an exercise in sly camp, the expression of a gay sensibility so cautious that it can hardly bring itself to mock its objects openly’.[3]

Wood is characterised in terms not just of not being heterosexual but also of so failing in masculine identity (as ‘son of the soil’ who operates in the open frank air rather than the guiles of a very feminised closet – the gendered binaries are frankly embarrassing but typical of the 1990s) that he cannot even come clean about his sexuality. Darnaude accepts that gay men had to ‘hide’ and justifies the fear that prompted that hiding in the homophobia of others ranging from the attitude in Cedar Rapids’ gossip that ‘gay and lesbian subculture was tolerated, so long as it remained invisible’ to the painter (and mentor also of Jackson Pollock to similar effect on his sexual expression I would say) Thomas Benton who was ‘wildly homophobic’.[4]

Very little space is allowed in either reading, though at least Darnaude’s is less offensive, if not significantly more respectful of the means by which people form ways of living out of multiple interacting, and sometimes contradictory, causative factors that impinge on the process. The simplistic notion of the closet needs to be revised now and is less prominent in Tripp Evan’s book, though it is acknowledged as a factor – it has to be. For living as a queer man is a performance of complex intersecting scripts available to them and us by the presenting context. I tried to use this idea of scripts for living queer life in an earlier blog (which can be accessed at this link) but have since found it explored in some detail in the work of Jeffrey Escoffier, though I have yet to go to the primary texts – the new one is priced at £100 in the UK and that is my excuse for not doing so until I can access a library. My account of it here relies therefore on an author interview and a review of a collection of his major essays in the current number of LGR.[5] Vernon A. Rosario in his review points out that the concept of ‘sexual scripts’ which guide behaviour, thought and emotion were developed by sociologists William Simon and John Gagnon. He goes on to describe Escoffier’s contribution as a description of:

… the three forces that shape sexuality: “cultural scenarios provide instruction on the narrative requirements of broad social roles; interpersonal scripts are institutionalised patterns in everyday social interaction; and intrapsychic scripts are those that an individual uses in his or her dialogue with cultural and social expectations.” …[6]

I do not expect a reader to relish the complexity this adds to the understanding of queer lives but I would like to recommend its greater proximity to the truth of how people’s lives are formed in both lived performance with others, their rehearsal in oral and simpler written forms (like gossip and conversation in the one form and letters, diaries and so on in the other) and finally in retrospective autobiography or biography. I hope we can see these interacting and intersecting forces operating in the examples of Grant Wood’s performed and rehearsed life in what follows without overmuch reliance on the use of the otherwise useful sociological jargon in this passage.

Darnaude gives a good press to the fact that Wood’s wife, Sara Sherman Maxon, even after their divorce (on the probably untrue grounds of physical cruelty to Grant) didn’t ‘care about her husband’s sexuality’.[7] Indeed, she seemed as if, in a biography she began but never, according to Tripp Evans, wrote beyond a few introductory paragraphs from which the following citation comes, clear that she could ‘out’ him without overmuch worry on her part, although she did not. She writes in 1958, as cited by Tripp Evans:

Oscar Wilde’s genius runs just as purely and clearly today as if the world did not know how he spent his last years or the reason behind that final degradation. There is some parallel [here,] as we shall see.[8]

Darnaude misquotes this piece and uses it to say that ‘she didn’t care about his sexuality’, but it nevertheless spends too much effort in typifying gay identity as if it were indeed the same in all people of ‘the Oscar Wilde sort’ as E. M .Forster’s Maurice describes them to his GP and still sees that life as one of ‘degradation’. In every way gay identity (considered as a commonality and sameness in a group of people) becomes a kind of trap, even when treated empathetically. Escoffier’s vision rather shows that queer lives are multi-formed and of complex aetiology, sometimes in each case, and not reducible to an ontological category of person. Indeed the intersection of the three basic scripts in our lives ensure that they are never just determined from something external or outwith intrapsychic work that itself shapes something of much deeper interest than a common identity, in which the purpose of symbols that hide a behaviour or trait is not just that of hiding and that the codes by which we live do not just exist to mean something else but themselves. In brief this is why people like Derek Jarman preferred the term ‘queer’ (a term often used of Wood and his painting, although with a different intent to Jarman or to those who later use it as merely a slur on the person) to other terminologies.

Wood’s life was subject to gossip in his home town of Cedar Rapids and that in itself became a source of scripts he internalises and transforms – like the name of the Butterfly Café, where he drank coffee with Arnold Pyle Eric Knight (the Englishman who was the original of the Sultry (K)night according to Tripp Evans) and Park Rinaud, all of whom he may or may not have had varied kinds of relationship whilst they lived with him in some role or other. Such roles and relationships are more than masks – they are institutional scripts that mould new forms of inter-being, just as the Cedar Rapids community living in ice trucks did, surrounded by WOOD that looks like fleshy limbs, not because it is hiding, whilst simultaneously coding sexual identity but because our reactions to flesh and wood, bark and skin form part of our armoury of knowing the world, whatever our sexuality.

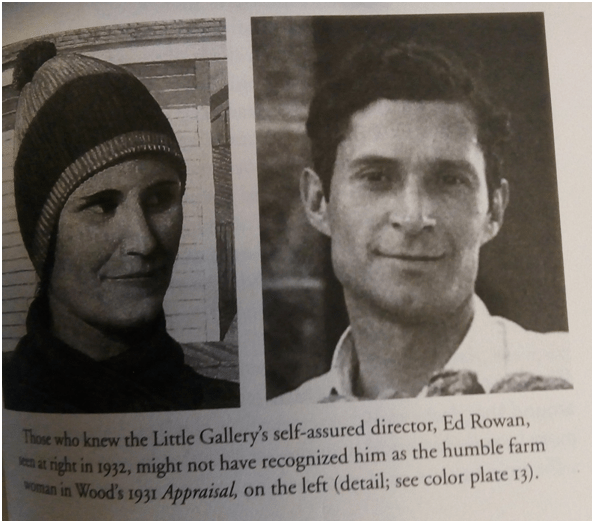

Gossip becomes a subject of his painting in his wonderful painting, An Appraisal, of 1937 (see below this paragraph) and Tripp Evans’ reading of this is wiser than the generation that spawned it, not least at showing how it uses role play and appearance under disguise not to reveal one hidden truth but to show the play under which aegis role-play and performance exist in our lives. Tripp Evans shows, for instance, that the country woman selling or showing her rooster or cock hen in this picture to a sophisticated and rich urban female visitor to Cedar Rapids is in fact modelled on the face of Edward Rowan, the far from simple rural man who was the director of Cedar Rapid’s Little Gallery, ‘(y)oung, urbane, handsome, and endlessly energetic’, and who saw himself in one cited remark by Tripp Evans as some kind of Lorenzo de’ Medici ‘paying obeisance to a Botticelli’ (by which he meant Wood).[9]

There is a use of playful disguise and conceptual fluidity that is much more than an exercise in ‘hiding’ one’s own, or another’s sexuality, though the pun on the appraisal of a ‘cock’ is, as Tripp Evans makes clear much more bold than any play of which Robert Hughes thought Grant Wood capable. Tripp Evans says, and this insight alone shows the superiority of his interpretations of the ‘queer’ nature of these paintings that transgress many boundaries and not only ones of gender and sexual orientation, that his ‘best work always operated on multiple public and private levels, none of which may be mutually exclusive’.[10] That the model for the city woman buying the cock was the possibly lesbian partner of a friend of Wood, known for the masculinity of her self-presentation is certainly part of the private reference and explains why masculinising jokes might have proceeded from her known ‘gruff nature and salty vocabulary’.[11]

The interplay in this picture is virtually a case study of the intersection of cultural scenarios, interpersonal scripts and intrapsychic scripts identified as formative of specificities of queer life by Escoffier. The latter argues in his interview in GLR that even the manner of interpersonal interaction that we call ‘sex’ between men was as fluid as some identities and determined by different kinds of script such that the choice of sexual partner owed in the 1930s a lot to the ‘idea of not having a firm identity’.[12] This may surprise some but would have been at the forefront of an artist’s mind, such as Grant Wood, who transitioned from expressionist styles that were, as Tripp Evans, shows described in the period as un-American because they not masculine or ‘hard’ enough. Wood moved from a painting of overlapping colore qualities to more distinct designs built of patches of colour bordered by hard lines. In a nutshell, this shift is often read as based on the masculinist bias of Thomas Hart Benson in his ideological invention of an image of a hard American masculinity of style which he labelled Regionalism and with which Wood became associated. But though he began to emphasise disegno qualities based on clear lines, Wood’s lines were so often curved lines – which have always been associated with femininity and which earlier readings of Wood associated with fertile Mother Earth icons.

Tripp Evans rightly shows us that however much credence we give to the normative association s of the masculine / feminine binary with a straight line / curved line one, it is nonsense to see Wood’s interest in the ‘curve’ as an affiliation with the feminine, as the art historian Wanda Corn does. He looks in detail at the tremendous 1936 landscape Spring Turning, which he traces to the mixed scripts of the physical culture movement, the necessity to show buttocks in male nudes to avoid full frontality, and Thomas Eakins’ use of male nudes to speak about an ideal of relationship between ‘man’ and nature.[13]

Tripp Evans’ reading of this painting is unequivocal about what Wood does to the relationship of landscape and male body but is not primarily about a coded homosexuality, although perhaps Alexander Woollcott may have found it so. If anything it is about a generalisation of queer desire into something that is about how nature is ‘turned’ by scripts of possible interpersonal desire, such that the ideology of the natural is constantly subverted. This is so with all those tremendous landscapes divided by curving clefts and penetrated by phallic symbols of the most obvious sort, which Tripp Evans sees throughout the ‘Regionalist’ work, whatever Thomas Hart Benson might have thought of this.

Wood’s evocation of the nude male body in Spring Turning is more than just a metaphor about natural beauty, of course – it is an image of desire and consummation. (As one reviewer noted, Wood “knows how to mold (sic.) hill masses, and how to plow (sic.) and plant them with rhythm.”) Not only does the artist provide a clear target for our gaze – the darkened creek mouth between the two hills – but he also guides here with the directional arrow of a plowed furrow; … Such an insistent privileging of the homosexual gaze may explain the work’s purchase by Alexander Woollcott, the flamboyant theater (sic.) critic who wrote for the New Yorker.[14]

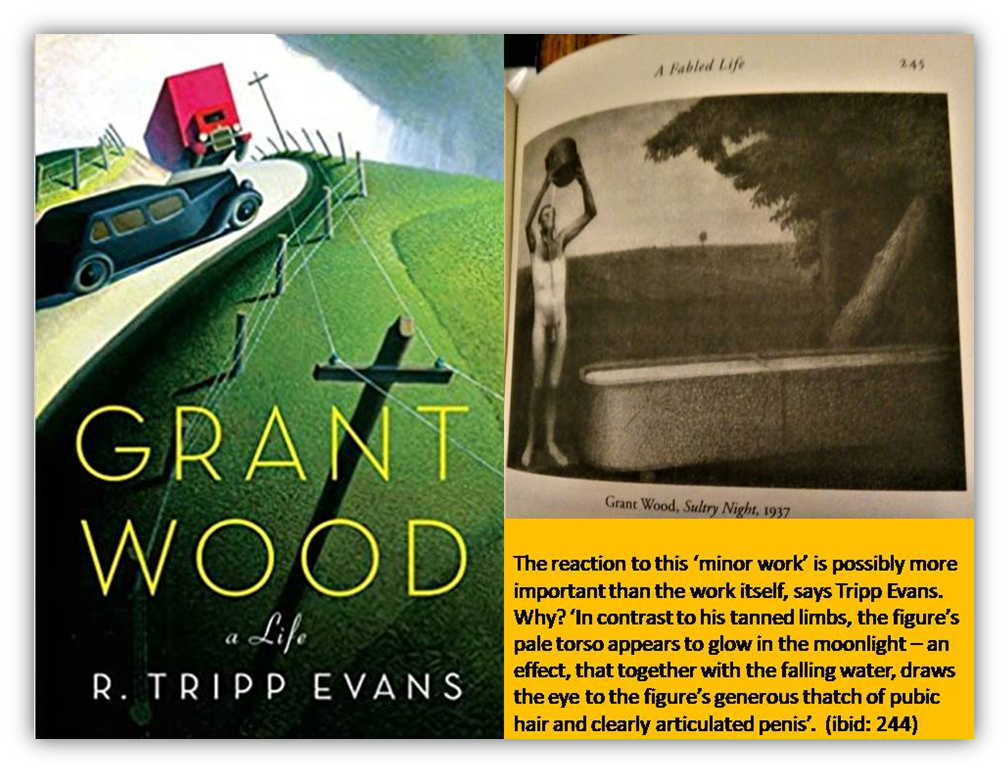

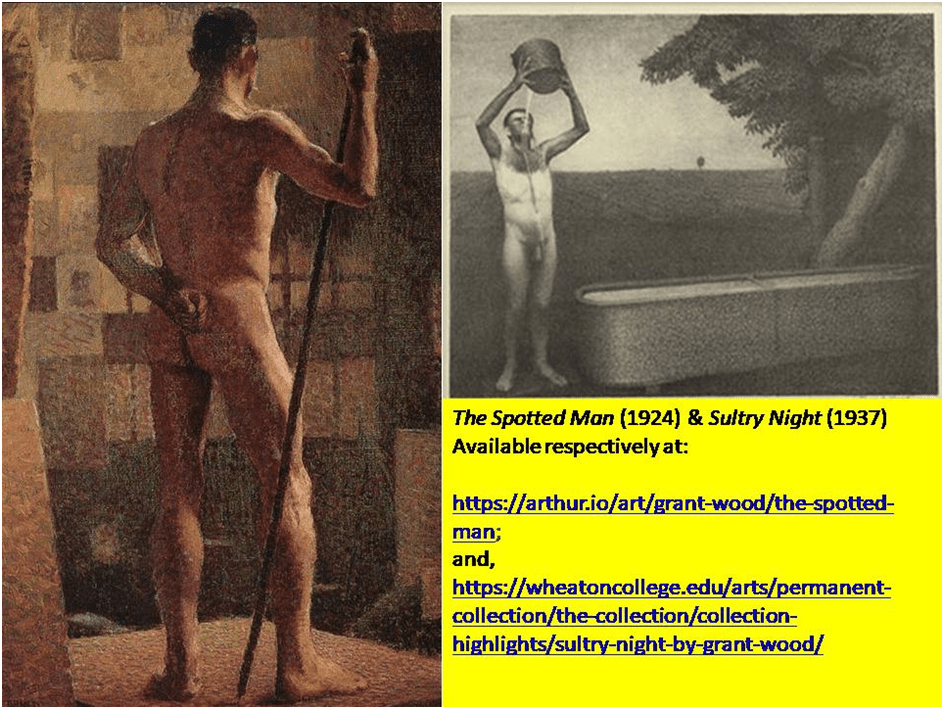

Wood’s training in life-class nudes resulted in his early The Spotted Man of 1924 referring to the ‘feminine’ pointillist style he acquired in Paris and there is nothing that is not conventional about this nude, although it shows his facility with painting buttocks. It does not prepare us for Sultry Night of 1937, an extant set of lithographic prints (now rare) that were originally intended to plot an oil painting that, owing to the shocked feedback and accusations of homosexuality the lithograph raised, Wood mutilated before allowing it to be widely seen (the mutilated colour oil version can be seen on the website at this link). Tripp Evan’s exhaustive work on the lithograph not only identified the most likely model as the Englishman Eric Knight (a very sultry Knight) but shows how wood combined scripts from his personal life (his ‘puerile’ liking for naughty bathing), the texts of the social hygiene movement and the vast tradition of classical and modern compositions featuring bathers that had taken new life from Cezanne.

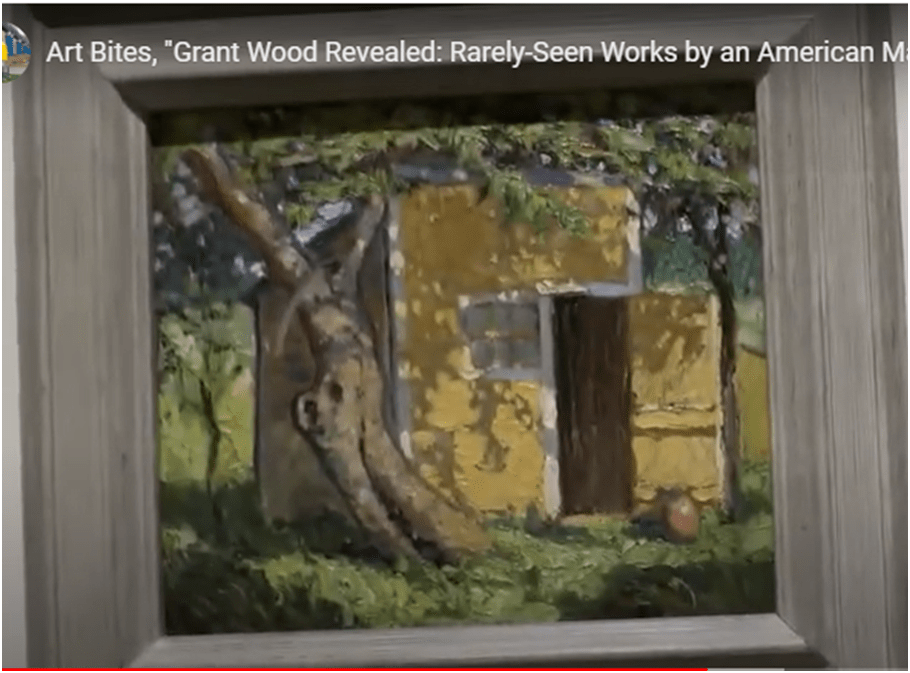

Sultry Night not only guides the gaze to the model’s penis, the woody symbolism in this painting isolates single trees – one on the horizon and one raised diagonally from an equally phallic-shaped water tub. It is indeed the same tree, according to Tripp Evans, that appears in the 1922-3 Van Antwerp Place There probably exists no more anthropomorphic example of a tree than that in the latter with its clefted legs and raised arms (illustrated above) but in Sultry Night the tree is more singular – a body part rather than a body. It is all that remains of the scene in the mutilated version.

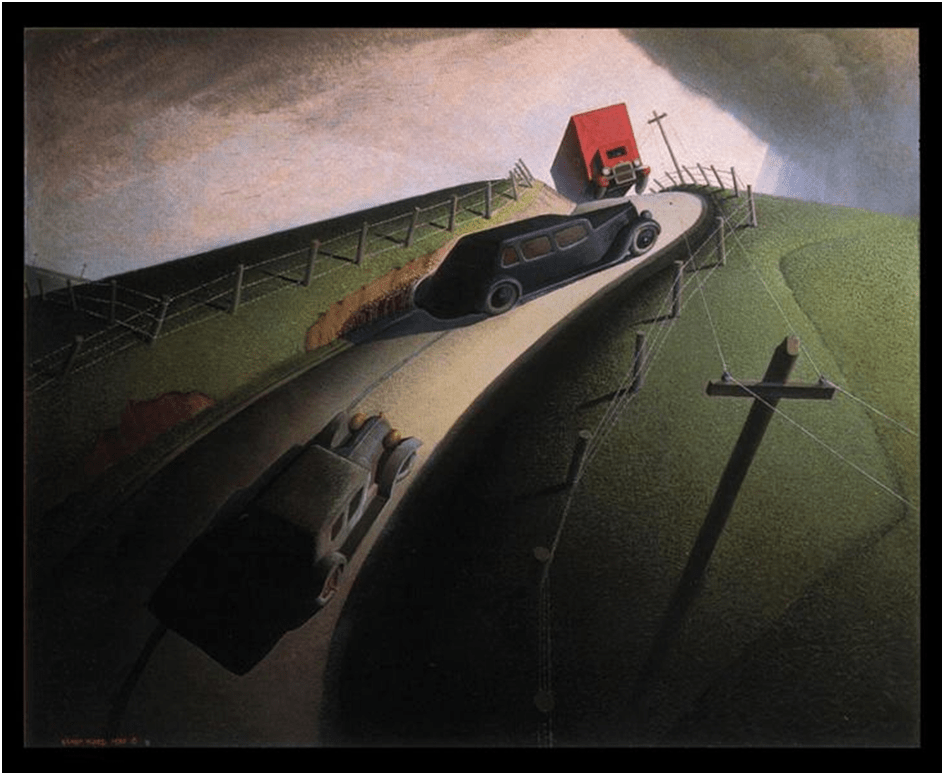

But looking at Wood’s work does not confirm that here we see neither Robert Hughes’ ‘timid and deeply closeted homosexual’ nor, I would say, Darnaude’s master of secret codes – though some coding there inevitably is. For Wood is a complex person whose work explores the potentials of a self that refuses to cut itself down to any one category in my view. That some saw him as ‘asexual’ still seems one of the feasible alternatives. What is clear is that he rather exulted in producing ‘queer’ images, as this – without any necessary reference to sexuality – is what his contemporaries called them. The aim is to estrange the norms he evokes – hence the power of American Gothic and Death on the Ridge Road of 1935. The last is possibly my favourite painting of his, for it rejoices in the hurling certainty of disaster and a world at with an odd perspective on both nature and art (and perhaps science too). It appears to generate a desired ending from things that emerge from both shadows and light, its object appear to fall as they try to stand alone and its landscapes dive into nowhere. Only Edward Burra achieves this effects for me otherwise and he too is a queer artist in every which way.

All the best,

[1] Ignacio Darnaude (2021) ‘Grant Wood Left Tipoffs All Over’ in The Gay and Lesbian Review (Vol XXVIII, No. 6 Nov-Dec. 2021) 19-22.

[2] Ibid: 20

[3] Robert Hughes (1997: 439 – 442) American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America London, The Harvill Press

[4] Darnaude op.cit.: 19, 22 respectively.

[5] Jeffrey Escoffier (2022) “In porn there are scripts at various levels” [Interview] & Vernon A. Rosario (2022) ‘How We Joined the Sexual Revolution: Jeffrey Escoffier – Sex, Society, and the Making of Pornography (review)’ in The Gay and Lesbian Review (Vol XXIX, No. 1 Jan-Feb. 2022) 21 – 23 & 38 – 40 respectively.

[6] Escoffier op.cit.: 39

[7] Darnaude op. cit: 21

[8] Sherman draft cited by R. Tripp Evan’s (2010: 311f.) Grant Wood: a Life New York, Alfred A. Knopf

[9] Ibid: 139

[10] Ibid: 142

[11] Ibid: 141

[12] Escoffier op.cit.: 22

[13] Tripp Evans op.cit.: 242

[14] Ibid: 243

3 thoughts on “This blog is based on my own belief that the writing of a queer ‘life’ (whether as biography or autobiography) is fraught with difficulties that are sometimes also experienced in living such lives. I test it by examining R. Tripp Evan’s 2010 book, ‘Grant Wood: a Life’.”