Watching Chloé Zhao’s Nomadland – a blog.

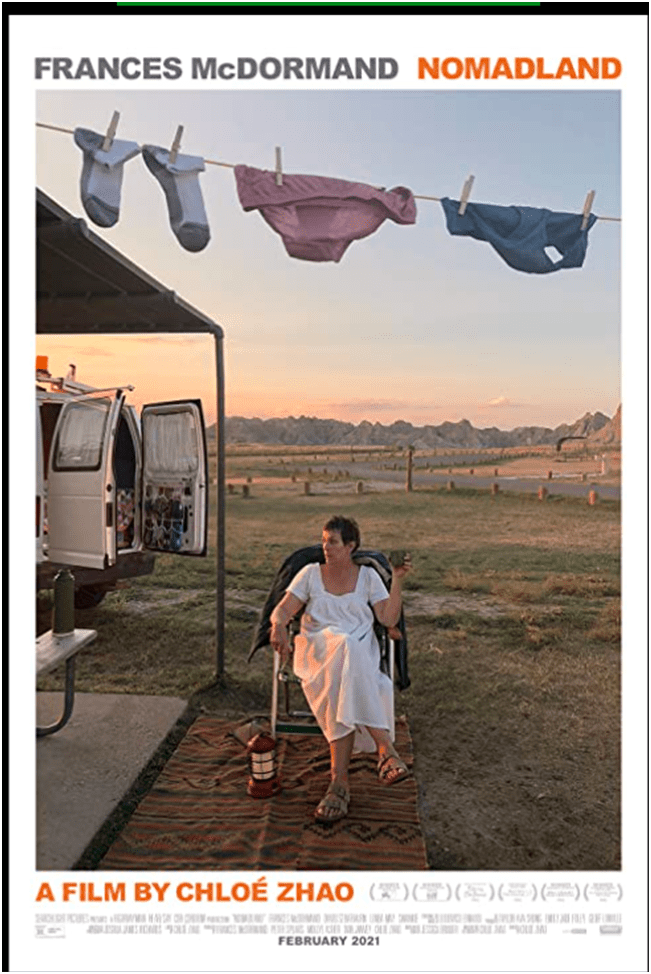

It is quite usual I suppose when considering a film on mainstream cinema to make much of its cast, but despite the wonderful achievements of its professional actors – particularly Frances McDormand – in this case you feel you have to start with its non-professional cast. Modern-day nomadic life in the USA is the fact that this film dramatises, finding its causes in the complex concatenation of factors that come together in the lives of its characters and the settings in which they for a short time come together as a group, including some amazing footage from the inside of an Amazon ‘fulfilment centre’. So this page listing the cast is a good start for us (follow link). But before looking at this consider this comment by Justin, who saw the film with my husband Geoff and I: commenting on some of the skills of Frances McDormand as an actor, he said that you could guess the characters who were, as it were, playing themselves by the closer attention to their stories demonstrated in the film by the manner in which Dorman enacted listening to their stories – a performance so profound it is the ‘real’ thing and draws attention to the role of listening in paying respect for others, without reducing them to the aetiologies of their present psychosocial condition. And this comment strikes deep into what this film is – a means of knowing the lives of others such that they are not reduced to the psychological and social phenomena they might otherwise be being used to illustrate.

And this is true too of the tropes of the film and the genres it inevitably uses to tell its tale – such as the road movie, the exploration of the emotional and narrative resonance of North American transcontinental journeys in novels and films – from frozen uplands to the emotional turbulence of the sea and back again, including, as Peter Bradshaw points out The Grapes of Wrath, since this film does for the 2008 crash what Steinbeck did for the Great Depression of the 1920s.

So they have become nomads, a new American tribe roaming the country in camper vans in which they sleep, looking for seasonal work in bars, restaurants and – in this film – in a gigantic Amazon warehouse in Nevada, which takes the place of the agricultural work searched for by itinerant workers in stories such as The Grapes of Wrath. Zhao was even allowed to film inside one of Amazon’s eerie service-industry cathedrals.[1]

The frozen scenes in particular serve well to demonstrate a landscape used to tell of emotional states (as in the recent film – and the engendering medieval poem itself, The Green Knight – with the cold and white of snow telling even of acceptance of mortal resignation and passage hence as well as the cold-heartedness of the cyclical operations of capitalistic cycles of regeneration to which human lives and organisations become fodder. Bradshaw, bless his heart, struggles with the film’s refusal to be determinedly anti-capitalist, as in this beautiful set of closing comments:

It is more of a group portrait and a portrait of the times, brought off with exceptional intelligence and style. Arguably it is not angry enough about the economic forces that are causing all this but it still looks superbly forthright. There is real greatness in Chloé Zhao’s film-making.[2]

This is like ‘wanting to have your cake and be angry at it for causing weight gain too’ – and is ultimately a fully human contradiction, too human to appear such. But this film could never be simplistic about capitalism even in its most egregiously exploitative forms such as the seasonal working arrangements and zero hours contracts of Amazon in Nevada. It is hardly worth the ink to weigh-in against the film’s refusal to be as hard on Jeff Bezos as he deserves as a global union-busting employer – the ‘free’ economics of casual seasonal labour appear to Fern, played by McDormand, to be able to provide pay good enough to pay back debts accruing to the wastage of necessary resources for the modern nomad – a van to live and travel within – when it breaks down and repair indebtedness to her sister who lends her money to support the ‘traditional American (nomadic) lifestyle’, she at one point describes Fern as living. This kind of lifestyle will inevitably find the neoliberal model of economic arrangements an aspect of its freedom, since it is honest about the emptiness of the legal frameworks that claim to protect the dignity of labour whilst (sometimes) imprisoning it in anomie and alienation from the realities of life and death, until they can be pretended to not exist no longer. In that sense, the ‘greatness’ of Zhao is the same greatness as authors like the Gawain poet – a greatness that sees no hope in failing to encounter the ‘smell of mortality’.

Mortality is the truth faced by this story. Mark Kermode however is right to say: ‘there’s none of the raging chaos or cosmic disharmony of his work in her altogether more benign portraits of humanity’ compared to that in Werner Herzog whom Zhao claims to derive influence.[3] And indeed Lear’s:

Poor naked wretches, whereso’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your loop’d and window’d raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? O, I have ta’en

Too little care of this! Take physic, pomp;

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou mayst shake the superflux to them,

And show the heavens more just.[4]

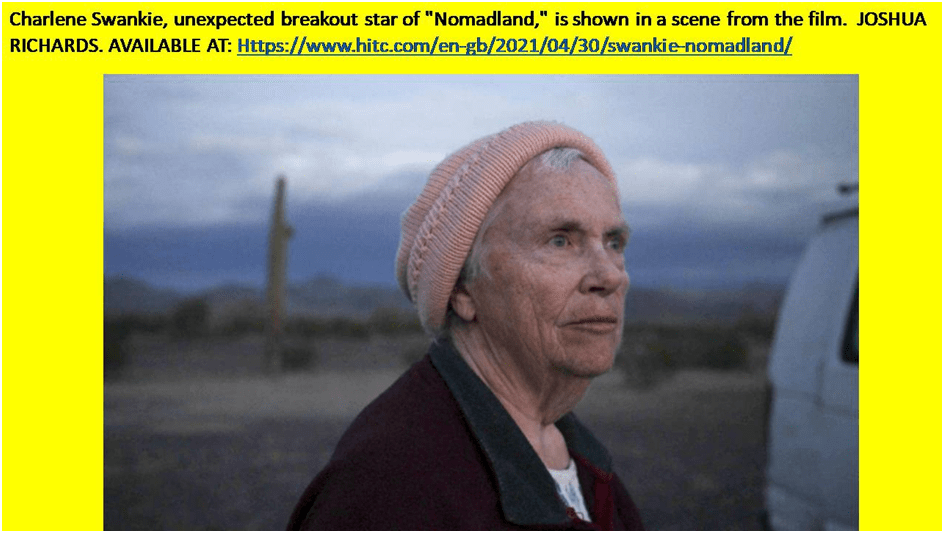

Lear’s monarchical paternalism is an enactment of the state dreaming itself as just and equable (in wish if not in reality) but meanwhile the victims of homelessness must find a means of making their own lives and deaths meaningful to themselves and even we of the left have to acknowledge the right of the displaced to find meaning in what others want to see as degradation in order to sweeten the sense of their imprisonment in contractual arrangements that enable housing. There has to be a subject position inhabited by the marginalised that is not just that of victim and it is to this purpose that Zhao helps them, including those enacting themselves in the film, to build their myths. One cannot help but love this in the character of Charlene Swankie.

The fictional Swankie dies and the group each throw a stone into a communal fire in the desert to commemorate her. This is a ritual to offer the kind of meaning that a life dominated by the rules of bondage of settled and stable capitalism (itself a myth as economic depressions show when the marginalised still bear their cost whatever the supposed legal framework). To be ‘houseless’ is different from being ‘homeless’ as Fern insists. Will Gomperz for the BBC states these issues beautifully – the origin of the myth of individual freedom in the American ‘pioneer’ tradition and American transcendentalist writing (Emerson / Thoreau / Mark Twain) and the material reality of broken vans and bodies:

The film shows you that, along with the hardship and the heartache, there is also serenity in this way of life, even a kind of euphoria – without the burdens of a house and possessions you can have a glorious and very American freedom in the lost tradition of Emerson and Twain. But what happens if your van – or your body – shows signs of collapse?[5]

That the myths of freedom under ‘houselessness’ fail to acknowledge the fact that for some this condition has no equivalent to that found by Swankie in dying and by Fern in learning from Swankie. Fern learns to dispose of the entrapment of ‘possessions’ for ‘free’ to those that want them (in the wonderful scene in which she returns to the dying ands dead town of Empire to empty the clutter of her old home’s garage. She learns (and this is a difficult one for a socialist to articulate) to accept the grossly unfair and unequal distributions on which Bezos makes his millions because seasonal zero-hours labour pays a bill without bounding one to settlement that involves the terms set by others who will exert their control over you.

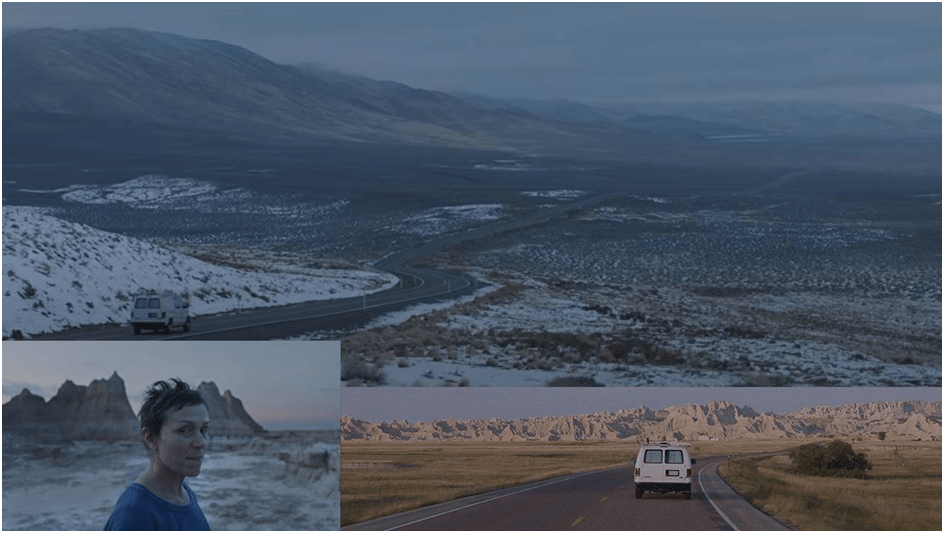

The critics who attempt to make this film appear to be a version of the post-apocalyptic legend, sometimes citing Mad Max – go too far in interpreting the love of barren landscapes as a prediction of post human bareness. This is not about the end of the world but like The grapes of Wrath the ways in which economic cycles necessitate a cycle of endings in order to allow for the re-establishment of new myths that equate hope with productive novelty in abundance is constituted in capitalist economics. It is a film that equates ritualised biological and quotidian cycles (again like The Green Knight) – of death and life, perhaps even of the seasons, dawning mornings and the setting sun of early evening. Look for instance at this definitive shot:

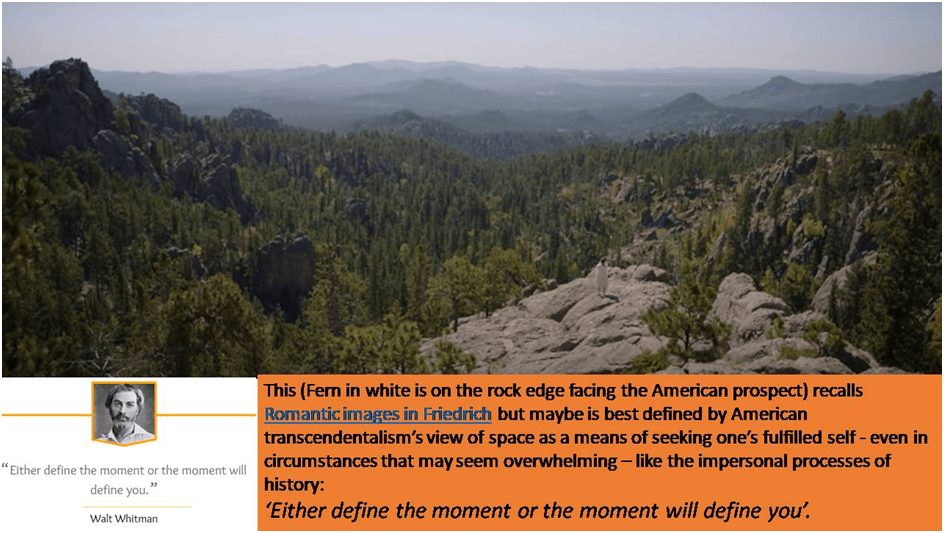

I cannot remember whether this is a shot to the east (with the sun rising) or to the west (with the sun setting). In either case the same melancholic inevitability of the cyclical pervades, as in the film as a whole. Landscapes of great grandeur pervade the film as either a setting for Fern or imagined as filling her vision and redefining her in terms of their largesse and largeness – though the truth that she remains a small cog in something larger never gets forgotten. See the example below for instance. Fern in dressed in white and stands near the edge of a rock facing an American prospect). It recalls Romantic images of European origin (in Friedrich for instance). Its effect though is best defined by American transcendentalism’s view of space as a means of seeking one’s fulfilled self – even in circumstances that may seem overwhelming – like the impersonal processes of history: ‘Either define the moment or the moment will define you’.

This is a source that means that we are not letting Amazon off the hook for attempting to reduce human labour to something entirely alienated from human values but that the means by which we combat it may mean, in the very short-term at least, living with the ways it is redefining the meaning of individual liberty and finding therein something we can value ourselves for.

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass(Song of Myself, section 1)[6]

This is more than a matter of taste. It is related to the fact that art acknowledges contradictions that political analysis merely analyses and, in doing so, helps human beings to live within them until they force themselves into another kind of resolution. See this film. It matters – immensely!

All the best,

Steve

[1]Peter Bradshaw (2021) ‘Nomadland review – Frances McDormand delivers the performance of her career’ in The Guardian online (Fri 30 Apr 2021 08.37 BST). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/sep/11/nomadland-review-frances-mcdormand-chloe-zhao

[2] Ibid.

[3] Mark Kermode (2021) ‘Nomadland review – Chloe Zhao’s triumphant ode to community’ in The Observer (Sun 2 May 2021 08.00 BST) Available in https://www.theguardian.com/film/2021/may/02/nomadland-review-chloe-zhao-frances-mcdormand

[4] Shakespeare King Lear Act 3, Scene 4. Available at: William Shakespeare – King Lear Act 3 Scene 4 | Genius

[5] Will Gompertz, (2021) Arts editor BBC, ‘Nomadland: Will Gompertz reviews film starring Frances McDormand ★★★★☆’ (17th April) available at BBC Online https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-56773244

[6] For a commentary see https://americanliterature.com/song-of-myself-study-guide