‘You … “as Virginia [Woolf] once told Stephen Spender, ”have to be broken by things before you can write about them”. It was this, one suspects that T.S. Eliot meant when he told her “the young don’t take art or politics seriously enough”’. Can reviews really help us to know the qualities that make a book readable and/or valuable: a case study using Will Loxley’s (2021) Writing In The Dark: Bloomsbury, the Blitz and Horizon Magazine London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

I have found it matters which reviews you read of new works that appear to be of interest from their subject matter. This was the case when I came across an excellent review by the wonderful Daisy Dunn in the Literary Review for July 2021 of Will Loxley’s debut historical narrative. It tells of the interactions of writers that were part of, or circulated around, the great ‘names’ we associate with the Bloomsbury Group and, although it is an entirely different historical phenomenon, the literary magazine Horizon. It fired my interest more and encouraged me to read the work. What though might have happened ifI had introduced to the title by another review. Let’s take the VERY brief one, for instance, of the same book, by Alexander Larman on the 9th August 2021 edition of The Observer. It is so brief that it can be quoted in full:

Will Loxley’s first biography concerns the fortunes of Horizon magazine, the influential 1940s literary title that Cyril Connolly edited, George Orwell and Graham Greene contributed to and Evelyn Waugh vocally detested. Loxley has an engaging and readable style and there is a refreshing lack of reverence in his account of the bitchiness and backstabbing that the writers of the era (over)indulged in. Writing in the Dark is packed with intriguing, often hilarious, anecdotes, and although Loxley could do with toning down the more overblown aspects of his prose, still this is a promising debut.[1]

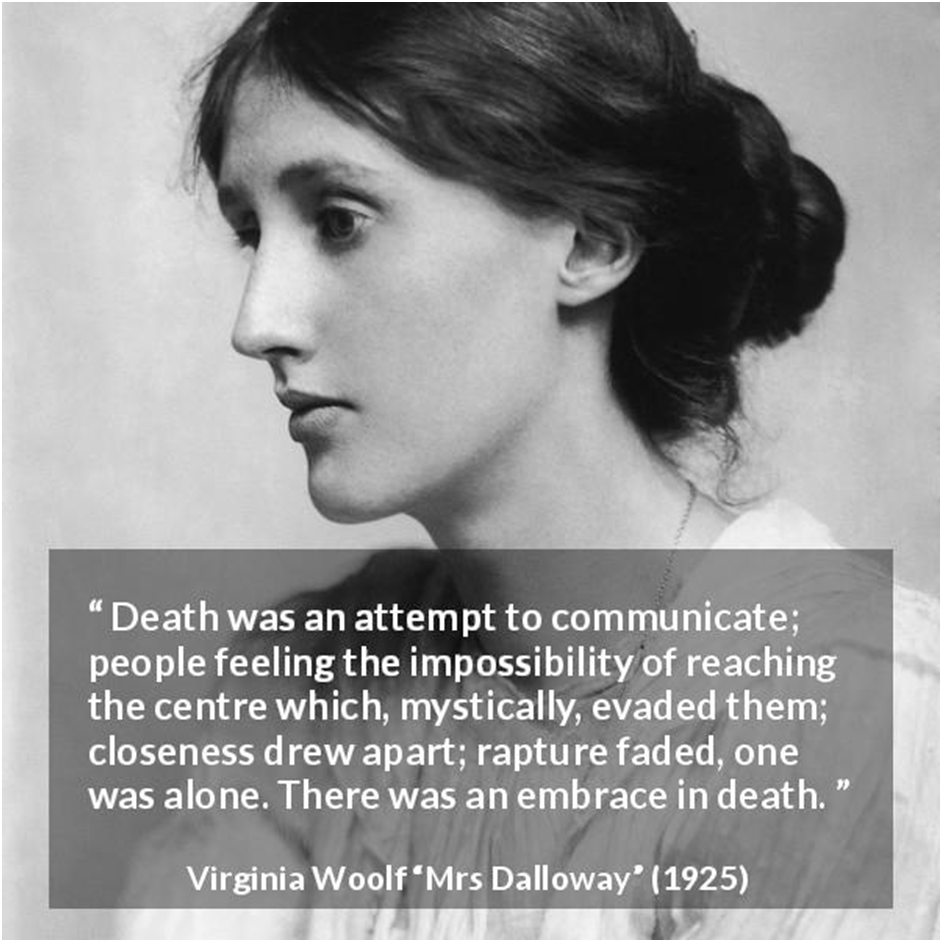

This review, as Daisy Dunn points out too, is of a first work by a young writer of non-fiction and characterises what kind of work it is by reference to its anecdotal tone and style. Dunn refers to its stories of writers as ‘vignettes’ and highlights their style silently by citing rich examples of Loxley’s allusive and dreamlike prose alongside Virginia Woolf’s already well appreciated and striking metaphors. His picture of the ubiquitous lamplighters who literally lit, when appropriate, the darkened streets of London as ‘the silent brigade of the gloaming, like folkloric guardians of dreams’ is after all not a long away from the exuberance of, in her cited reference from one vignette, of Woolf’s ‘guilt when she was having what she described, marvellously, as “a perfect day – a red admiral feasting on an apple day”. Dunn may be correct that a difference in the metaphoric habit is that, unlike this example of Woolf’s, Loxley’s prose can lack ‘light relief’ and the ‘jeu d’espirit’ of the writers who are its subject.[2] But her liking for this prose animated by rich reference makes her a better reader than Larman who only notices ‘the more overblown aspects’ of a debut writer’s prose. Personally I love his writing, mixing up his own metaphors with those of the richly allusive writers of the period in trying to capture the tone of the times and the actual density of the temporal experiences they describe, like this of the Blitz.

Lehmann was still standing by the bottom of the stairs when the next bomb struck. “There was another tremendous explosion,” he recalled, “the house seemed to clench itself like a fist for a moment, then silence.” He went to the door again. Strange, inexplicable sights, including a man in pyjamas walking through the dust cloud to his flat. … The moment when the house seemed to clench itself had been real – walls and ceilings and the roof testing the tensile strength of the building’s wooden skeleton. Under the impact of bombs, Lehmann later found, buildings could actually sway, as if on a pivot, so that those inside felt themselves to be on a boat in a bad crossing. …

Far from being evidence of the overwritten style of a debut writer I find this prose actually to begin to share the possible sensations excited by described events, including the ways in which they change on reflection in later time from the ‘inexplicable’ to the beginnings of an understanding of how buildings react to stress. He takes Lehmann’s stylistic character seiously here in focusing on that metaphor of the ‘clench’ and a good reader will do the same with his and experience that of which he and his subjects write.

Larman’s summary of the book is also deeply reductive in ways not explicable by its brevity – as I have already said, it deals with writers not directly related to Horizon: the rival publisher / editor, John Lehmann, for instance (who appears in the quotation above), whose links were to Bloomsbury and who fashioned an alternative vision of literature – immersed in civic and sexual politics and aimed at introducing debut writers to the world.

In fact if the book has a fault it is that kind of fault often found in debut works of having a historical scope too wide to not necessitate a very limiting selective focus on what the book deals with in actuality. And selectivity reveals a lot about conscious and unconscious bias in an author’s range of interests and perhaps their knowledge. In effect the guiding ideas do not relate to the facts that might describe the historical phenomena named in the title but the themes of the period that most interested Loxley, given that he also does tell some good anecdotes. But the vignettes feel to me, like Dunn, more focused on its selected themes than Larman admits. He makes the book appear trivial, which it very definitely is not. For Dunn the story of Horizon is ‘less central to the narrative of the book’, instead focusing on ‘a circle of writers who defied the blackouts to launch themselves on literary London’.[3]

In short this book is a debut writer’s book on writers making their debuts – in particularly challenging circumstances. For me, though, the selection of writers is too partial for that purpose and would have needed more, in this case on John Lehmann’s championship of writers now lost or remembered only at the margins of literature, such as Sid Chaplin (the County Durham ex-miner) or Ernest Frost (who devised a rather different and positive queer literature (in my opinion) now forgotten – see my blog in link), to modern readers. He published these and others in his own imprint and in Penguin New Writing, though the latter gets some limited coverage too (at least as much I’d say, as does Horizon).

The motivation of this enterprise is made important to themes highlighted by Loxley such as the ways in which the contrast between young and older writers was handled in the literary critical and writerly gossip of the time, and particularly in terms of the handling of politics, feminism and the topic of homosexuality (rarely about a more comprehensive sexual politics). But his scope limits our insight into the better known and upper middle-class characters, rather than the Ernest Frosts or Sid Chaplins who need more exploration – at least for a serious exploration to be attempted. Loxley never really draws out the themes I will focus upon – though they are there to be discovered as Dunn discovers them in part, focusing on the relationship between a young and an older generation of writers wherein, the ‘author identifies “a mutually beneficial relationship” between the two groups, enabling one to survive and the other to exist’.[4]

One intriguing and urgent theme is how the contrast in the meta-analysis of the proper subject of art is handled between older and younger generations of writers, to which tendency Lehmann was central, as was – and this book brilliantly makes this connection – Michael Roberts who railed against the insistence on tradition just as T.S. Eliot was becoming more and more comfortable in having established it as an orthodoxy.

Virginia’s frequent comparisons of modern poets to Wordsworth (all unfavourable) and as wannabe politicians versus the true poet was a criticism Roberts had pe-empted. Modern imitation of canonical voices was unavailing, he believed; it came off as insincere. Instead “new knowledge and new circumstances have compelled us to think and feel in ways not expressible in the old language at all.” John Lehmann called this language “the old poetic tinsel” – “Christmas-tree baubles that so many poets began to drag out again during the war (and were applauded for hanging on their dead branches)”.[5]

Earnest this is but the ‘levity’ she requests is a Woolf-like response of Daisy Dunn’s to the very serious point about the difficulty of attempting to change cognitive and emotional deep structures discovered in Lehman and Roberts by Loxley. Levity here would further undermine (since this venture is ill regarded in stable societies and even in unstable ones like ours) the capture of that structure of thought and feeling in the new writers. This is especially so since these particular new writers themselves, perhaps very wrongly as we have all found, felt such changes to be happening organically as a response to technological innovation. For the radical Spender of the book The Destructive Element the older generation were deluded in thinking that they were not political because their politics was latent rather than blatant, that writers require ‘awareness, first of all, that writing was always political, in the sense that it was moral’.[6]

In fact there was earnestness on the subject of politics on both sides of the debate between those we now see as classic modernists like Eliot and Woolf and those politicised moderns, whom Loxley bravely identifies most strongly with Stephen Spender. His was the most dogged of the voices of the political Left, until absorbed by the necessity to see the more pernicious faults of one-state socialism in Stalin’s Russia and an increasingly solid role in the establishment, that was to line his later post-war projects up for CIA funding in defence of ‘freedom’. Loxley is so precise in pinning down the difference in politics as perceived by Eliot and Woolf as the danger of modernity being characterised by a practical or even pragmatic ‘intellect and will’. He cites Virginia Woolf’s advice to Spender that politics was not a subject for the finer and more ‘serious’ passive sensitivities required by the artist, trained by experience and emotional response to know as:

Virginia once told Stephen Spender, ’[you] have to be beaten and broken by things before you can write about them’. It was this, one suspects, that T.S. Eliot had meant when he told her “the young don’t take art or politics seriously enough”.[7]

There was perhaps a truth in this beyond Eliot’s championship of the established and traditional but there is also something bold in Spender’s then insistence, brought back to light by Loxley that the sincerity of the suffering individual was of no use when what made us miserable was in fact the ‘public tragedy’ of a world seriously out of joint and driven to crises internationally, nationally and, by a process of reflection, personally by contradiction and inequality that require public (that is political) resolution.[8] With Lehmann, united over the tragedy of Spain in 1937, with Spender, Lehmann writes:

Creative artists, if they are to remain fully living people, if they are to fulfil their function as interpreters of their time to their own generation, fail to interest themselves in the meaning behind political ideas and political power.[9]

In my view of course it is a strength, and perhaps at a deeper level a weakness, of the book that it includes a goodly proportion of characters in its cast who saw their sexual-political experience as part of a much wider struggle, though hardly without important contradictions between them and in themselves. Isherwood and Auden broke from Communism it seems in part, in Isherwood’s telling of it because of their relatively openness as queer men at least to peer groups of their sexual lives.[10] It was in the re-evaluation of the great myth of ‘the fighting cock’, in Woolf’s terms, that perhaps older and younger generation came together politically in exposing what Loxley names ‘the great and deep ideological construction of manliness’. Yet she perhaps thought this explained the tragedy of even very modern sexual beings like Julian Bell, her nephew, who went to the Spanish Civil war and died there.

Even those united in political comradeship, as Lehmann and Spender were in believing in the role of literature in creating a ‘revolutionary movement’, at least in their war years, divided around issues I identify as those of queer politics: Thinking about Lehmann’s collection of poem A Garden Revisited Spender wondered why Lehmann ‘seemed to play it so safe, shirking the real in favour of the dreamlike. Why did he pretend to be heterosexual?’[11] Linking openness about sexual life to the necessity of political risk-taking may seem strange to us, who know the schizoid difference there came to exist between Spender’s public and private life in his sixties, apparently in deference to his second wife, Natasha, and in his distaste for homosexual ‘sterility’ as many contemporaries, normative or queer both, also thought. Christopher Isherwood, appalled that his mutual friend, Tony Hyndman, and lover of Spender (who introduced Stephen to Natasha) had been abandoned, felt that it was just a matter of Spender seeking in public ‘a new image’[12]

It is a pity in this respect that this book is relatively closed to the life of Peter Watson, who yet is named in its ‘Cast of Characters’. Similarly the link of Spender to Lucien Freud, though mentioned,[13] shows that the way, in this period visual art and literature were so strongly forging alliances and yet were in competition as means of accessing truth is not examined, although this relationship is paramount in Lehmann’s periodical publications. The putative sexual relationship between Freud and Spender remains a matter of conjecture but on that rides a lot of the weight of some of the ways the themes of Loxley’s book might interconnect. Privacy and image-making and preservation were to be the petard that broke down any nascent alliance of queer politics and a radical agenda in the arts was broken. That story remains to be told.

This however is a really enjoyable book. Read it. The story of Woolf’s last days is beautifully and starkly told. The respect of the writer shines through.

All the best,

Steve

[1] Alexander Larman, ‘In brief: Writing in the Dark; Dust Off the Bones; Looking for the Durrells’ – review in The Observer online (Mon 9 Aug 2021 09.30 BST). Available at: In brief: Writing in the Dark; Dust Off the Bones; Looking for the Durrells – review | Fiction | The Guardian

[2] Daisy Dunn (2021: 45) ‘Changing the Guard’ (review) in Literary Review (Issue.498 July 2021) 44f

[3] ibid: 44

[4] Ibid: 44.

[5] Will Loxley (2021: 179) Writing In The Dark: Bloomsbury, the Blitz and Horizon Magazine London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

[6] Ibid: 91

[7] Ibid: 176

[8] Ibid: 284

[9] Cited from (I think but the referencing is lax in the book) Lehmann’s autobiographical writing in ibid: 54

[10] Ibid: 15

[11] Ibid; 180

[12] Ibid: 73

[13] Ibid: 300

One thought on “‘You … “as Virginia [Woolf] once told Stephen Spender, ”have to be broken by things before you can write about them”. Can reviews really help us to know the qualities that make a book readable and/or valuable: a case study using Will Loxley’s (2021) ‘Writing In The Dark: Bloomsbury, the Blitz and Horizon Magazine’”