This blog is a postscript to an earlier one revisiting its errors in the light of Andrew McMillan’s new poem for Manchester Literary Festival. But it can be read without the earlier blog. @AMcMillanPoet

Not long ago I quizzed some words in a short essay by Andrew McMillan, possibly my favourite poet. I did this, in part at least, because I see him as an openly queer poet. His prose words in the essay opened up a problem, at least for me, in the way the queer sexual life relates to the poetry of contemporary queer male poets. Queer sexual life describes an interaction of bodies that has no desired, implied or expected teleological interpretation, say, in its relation to biological reproduction or some version of religious creationism. This is what I quoted in this blog (see link to read full blog).

‘Since queer theory first emerged, and perhaps before that, there has been a problem about naming pictures (I intended to reference pictures made of words or visual images) of male bonding, haunted by fears that any name given to the observed relationship is an over or under interpretation of what we see – a conscious or less conscious ‘bias’ in naming that action. And I’d argue perhaps that is even more complicated when we intuit the male gaze as a third term in that relationship since that gaze is attributed with the power of interpretation, and possessive naming in feminist theory. It is into this complex network of interconnectivity between naming and interpretation that Andrew McMillan has just stepped in an essay on why he writes poetry, saying, of his first poetry collection physical: “… I’d argue the real subject was the male body. …: what if that male gaze was turned on other men – only partly in a homosexual way, but also in a homosocial way?”[1] In the same essay on why he writes poetry, McMillan says: ‘I didn’t actively choose to be a poet of the body, or queer male desire, or masculinity, or any of the other labels that are put onto my work’.[2]

When I wrote that and my own later opinion of what this wonderful poet says about himself as a poet, I did not know a new work that was later made available on Twitter and the internet through the Manchester Literary Festival who commissioned it. But now I know it I can’t stop thinking about it and how it changes my view of things and the meaning of art I still like to label ‘queer’, rightly or wrongly in terms of the poet’s own intentions or motivations. This is how I concluded my blog by looking at an issue in the interpretation of photographs of male couples in a moment of perceived closeness.

I cannot be sure that I have established that it would be wrong to eschew the intention to be, or to write, things that can end up in being labelled as “a poet of the body, or queer male desire, or masculinity”. In my view perhaps these labels ought to be embraced in part at least, Moreover, I’d also question whether when “the male gaze is turned on other men” we gain very little by isolating the homosocial from the homosexual, as if we had a choice of how we perceive the difference based on the appropriateness of the object gazed upon. For ‘looking’ is never innocent of sexuality, body politics and gender diversity issues, nor is the social an arena free of the play of sexual determination. There is no ‘romantic’ separate from sex or I’d say vice-versa since to be romantic is just to adduce a story of interconnection in which sex was once, will be or, without or knowing, is already sexual. We just have to be clear that the latter is the not the hegemonic tool of our relational readings.

As usual, reading back I think I overstate the case. One only has to read Andrew McMillan’s poetry again, from any period of his career thus far, to see that He never runs away from those labels (“a poet of the body, or queer male desire, or masculinity”) he nevertheless says he would prefer not to be definitive of everything his poetry does. For this poetry proceeds from a place where body, masculinity, and queer male desire are all definitive subjects that interact with the other purposes fulfilled by a poem. But these purposes are legion and not somehow more limited when used in a poem on these subjects and therfore need recognition than being made invisible by a label.

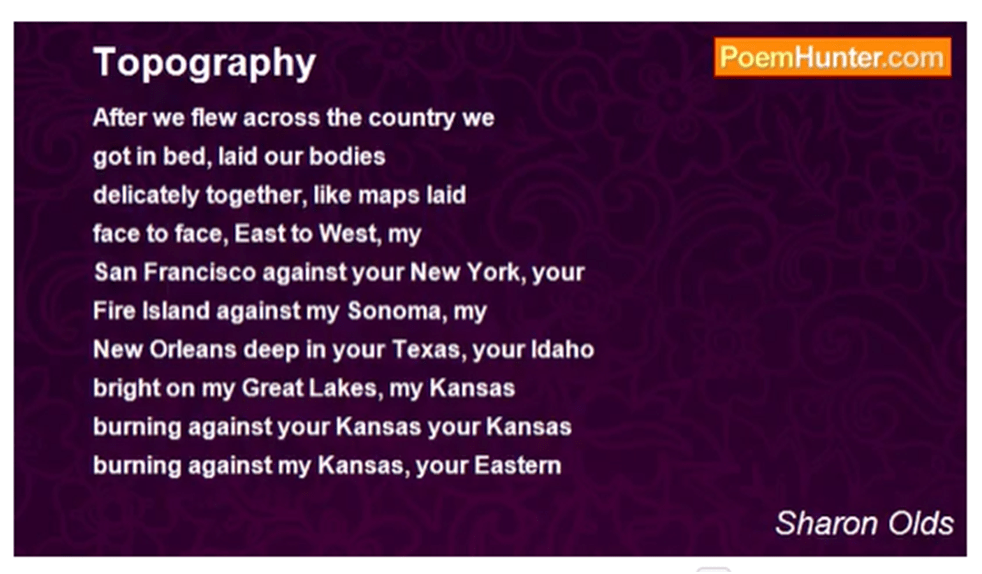

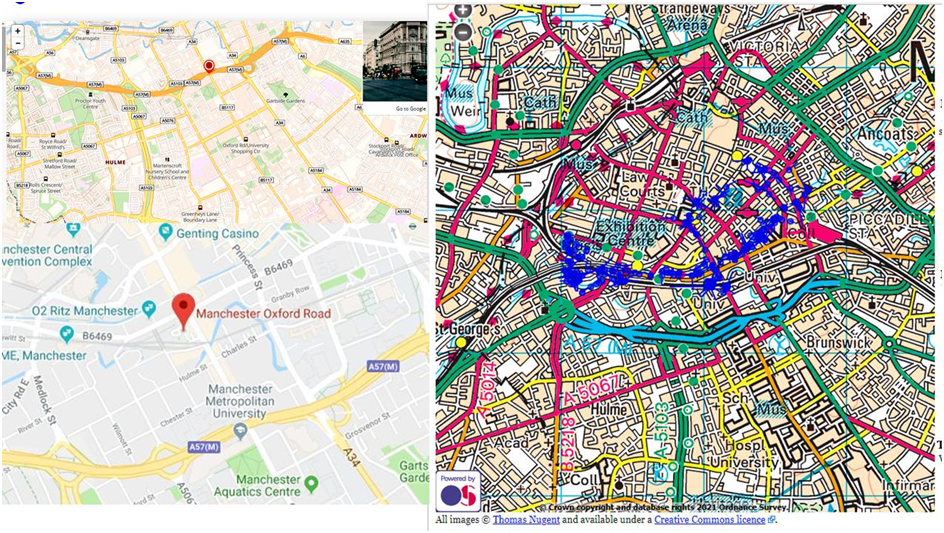

Hence it was great to see this poem (the vimeo can be downloable and watchable from this link and the text of the poem printable as pdf from the black box naming the poem at the top of the same page). And here I try to say the further thoughts on this issue that it prompted. It is titled as a poem about ‘place’ – the same place addressed by the other two commissioned poets, Hafsah Aneela Bashir and Reshma Ruia, The Oxford Road Corridor in Manchester. McMillan’s poem specifically addresses the concept of graphical representations of place – the meaning of topography – even in its title: topography: oxford road, map & key. The poetry of mapping is an honourable tradition in itself.

And it would be a mistake to see McMillan as writing entirely outside that tradition. He has read too much and is too intelligent a reader not to have taken into account a tradition even if he is not bound or constrained by its particular demands, even in the revisionary way T. S. Eliot spoke of in Tradition and the Individual Talent. For Eliot felt a true poet produced not a poem but a revision of a whole existing tradition and order of poetry. This is not a merely egocentric claim for any significant poet to make: it is an acceptance that one’s voice matter more than in its relation to something personal and of the current moment and when I think generously this is why McMillan is right to say that he is motivated to poetry beyond those personal and current moment themes summed up by ‘a poet of the body, or queer male desire, or masculinity, or any of the other labels’.

The necessity that he shall conform, that he shall cohere, is not one-sided; what happens when a new work of art is created is something that happens simultaneously to all the works of art which preceded it. The existing monuments form an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new (the really new) work of art among them. The existing order is complete before the new work arrives; for order to persist after the supervention of novelty, the whole existing order must be, if ever so slightly, altered; and so the relations, proportions, values of each work of art toward the whole are readjusted; and this is conformity between the old and the new. Whoever has approved this idea of order, of the form of European, of English literature, will not find it preposterous that the past should be altered by the present as much as the present is directed by the past.

And the poet who is aware of this will be aware of great difficulties and responsibilities.[3]

And those responsibilities are complex in their historical evolution as even Wikipedia’s account of ‘topographical poetry’ shows – constantly shifting away and back towards a responsibility of the poet to the recording of the interactions (cognitive, sensuous and emotional, and personal and political) between landscapes and the activity of body, mind and sense through which humans give meaning to places and supervenes to change them. McMillan is in fact showing how contemporary changes in the public meaning of the body, desire and gender have force on the meaning of place, just as topographical poetry has always shown human activity changing the meaning of supposedly physical realities.

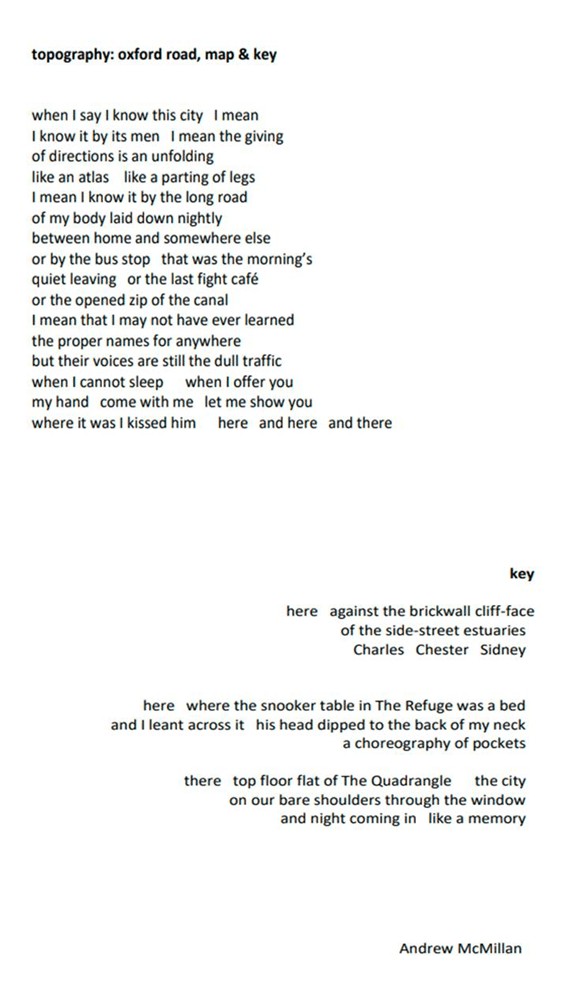

Here is McMillan’s poem, followed by a map of the area of Manchester it covers:

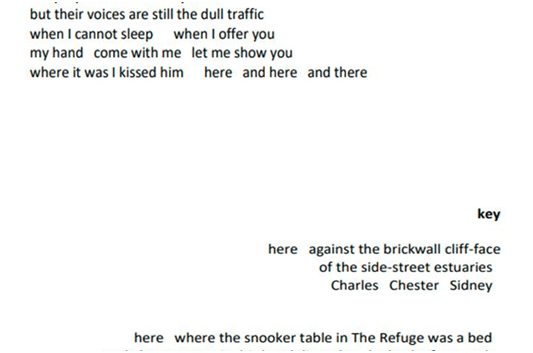

No map is complete without some kind of key to the relation of its parts and the names we use to define them in relation to each other, and McMillan uses the term ‘key’ in precisely this way. It unlocks an area in which the play of the body, queer male desire and masculinity get their meaning through the places they give new, or sometimes substitutive, significance to. As he says:

I mean that I may not have ever learned

the proper names for anywhere

For we learn to name places through absorbing ‘proper names’ given to them before our supervention, and to rename them through their function to us – as a ground for cruising for casual sex with men by men – is to change their being and to demand a new ‘key’ to those meanings and the names we give them. This is an act poetry has always claimed as its own territory – the issues of the body, queer male desire and masculinity only more recently. Oxford Road Corridor becomes a kind of backbone and a river, with ‘estuaries’ at the mouth of its confluence with other streets, whose names are those of men with whom we may have shared sex: Charles Chester Sidney.

And sites change their function – a snooker table at a known venue (it’s proper name and perhaps supervening function being ‘The Refuge’ ) becomes a bed; its ‘pockets’, a searching between each body of each other’s orifices as well as the repositories of snooker balls when they hit their targets. The function of language to ‘name’ is displaced from offering simple key related name to thing named to one which refers meanings to multiple simultaneous contexts, but yet again this has always been the function of poetry.

But that function extends to new ways in which poets or other ‘authorities’ exercise the ‘giving of / directions’. The act becomes a demand to ‘know’ (how rich this word in our tradition) the body of a man (like the long road that is Oxford Road and a road to some revelation of knowledge – Oz perhaps) and a body (see how terms shift) of potentially desired men. There is surprise and beauty in the metaphor by which the ‘opened zip of the canal’ locates male desire in the confluence of streets and remembers perhaps too, Canal Street, some slight distance North East (I think) of whatever interaction is referred to here.

And a poet is always a poet first and foremost, not their subject-matter and so here again, I can see the justice in McMillan’s rejection of labels based on either thematic subject or even simple unaccompanied topoi. Great poet’s know what they do when they talk about their hands and offer them, or invoke those of ‘another’ to be held in theirs have the metonymy of a written ‘hand’ in mind. The person addressed in such poems is always both a created character (or recreated memory) of the poem and the reader. Here are some examples:

This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou would wish thine own heart dry of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calm’d–see here it is–

I hold it towards you.

John Keats, ‘This living hand, now warm and capable’ Available at: “This living hand, now warm and capable” by John… | Poetry Foundation

Doors, where my heart was used to beat

So quickly, waiting for a hand.

A hand that can be clasped no more –

Alfred Tennyson, In Memoriam VII Available at: Poetry Lovers’ Page – Alfred Lord Tennyson: Dark House (poetryloverspage.com)

So, hush,—I will give you this leaf to keep:

Robert Browning Evelyn Hope Available at: Evelyn Hope by Robert Browning – Evelyn Hope Poem (poemhunter.com)

See, I shut it inside the sweet cold hand!

There, that is our secret: go to sleep!

You will wake, and remember, and understand.

The poet’s ‘hand’ in topography is a wonderful example too (perhaps better):

This is a poetry of the body as place for we move from encounters with the body either naked or behind clothing barrier (‘a parting of the legs … my body laid down … opened zip’) to be offered places receptive of the poet’s kiss (those indefinite topoi ‘here’ and ‘there’ seeming to be body places in the earlier context to literal physical places in which a kiss might be given just as the names of men that follow can be the names of streets flowing onto Oxford Road or men.

But the body part here that matters is the poet’s ‘hand’ offered retrospective to the amative events named or nearly named, perhaps only conjured from a context that is sexualised in its culture. And because the poet is going ‘home’ via the ‘long road’, I intuit a narrative in which the ‘hand’ offered is also to a lover or partner at home, an invitation to ‘know’ not only the city but the life of the city in the body politics of close affiliation. The ‘long road’ anyway is not primarily Oxford Road except by meta-association in the title but the poet’s whole body offered ‘down’ (rather than up) to male sexual desire, over which plays the ‘dull traffic’ of other man’s almost or effectively anonymous voices and who are not offered a hand here but a ‘pocket’ of self, like that in the ‘back of the neck’.

This poem is a queer poem and will take queer men by storm by its urgent insistence on the physical nature of their journeys but it is also not satisfactorily labelled a poem of ‘body, queer male sexual desire or masculinity’ because its first recourse is the analysis of different kinds of intimacy including that offered by the written hand as it scans the internal landscapes of both knowledge (‘when I say I know … I mean’) and what is ‘like a memory’. In my view it is a very great poem and trying to understand it has reconciled me to words that troubled me when I wrote my earlier blog.

But, heh! We all gotta learn!

All the best,

Steve

[1] Andrew McMillan (2021: 33) ‘The Body I Could Trust: On Writing and the Changing Voice’ in Ian Humphreys (Ed.) Why I Write Poetry: Essays on Becoming a Poet, Keeping Going and Advice for the Writing Life. Rugby, Nine Arches Press, pp. 31 – 36.

[2] Ibid: 34f.

[3] T. Eliot Tradition and the Individual Talent Available at: https://www.bartleby.com/200/sw4.html The use of the term supervent appears to be similar to the use of the term ‘supervenience’ in philosophy rather than everyday usage, despite the fact that some accounts date that usage well after the date of this essay: ‘Supervenience is a central notion in analytic philosophy. It has been invoked in almost every corner of the field. For example, it has been claimed that aesthetic, moral, and mental properties supervene upon physical properties’. (See Supervenience (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy))