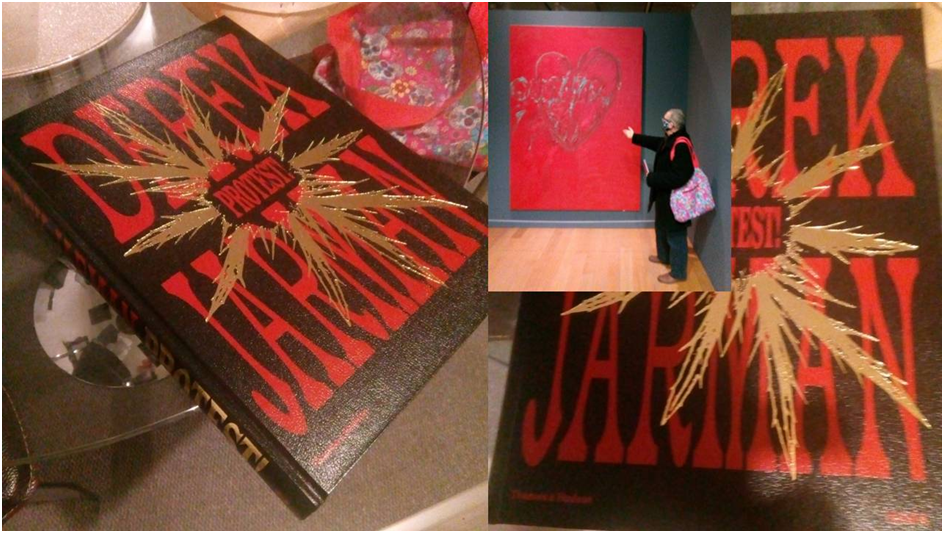

“If the paintings are palimpsests, the books are reliquaries, filled with asynchronous wonders. / … / … preferring to animate old revels by injecting them with a chaotic modern element”.[1] How and why the art of Derek Jarman defies time as we think we know it to be and as we think we know it works. This blog reflects on Seán Kissane & Karim Rehmann-White (Eds.) Derek Jarman: Protest Dublin, Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) & London, Thames & Hudson Ltd..

With Geoff, my husband, I visited Manchester to see this exhibition just before it was cancelled because of the pandemic a year and a half ago. We returned on a longer visit to include three days with the lovely friend I made, on Twitter would you believe, Justin Curley. Life events interact and in several blogs I want to show how Justin’s eyes (and heart and brain and spirit) helped me to see again things I thought I knew.

Jarman was a part of my own developmental history – as a person, an activist in queer politics, and more recently in the championship of art that is queer or queered from whatever period of history, medium or genre. Jarman as an artist and man underscored my current certainty that queer politics matters much more than the preservation of myths and teleological theoretical constructs about biological sex and which prioritise that latter construct over everything. The tyranny of this idea has paradoxically these days tied itself to a brand of a-conceptual feminism and LGB (without the T and much else) politics but Jarman nailed it early:

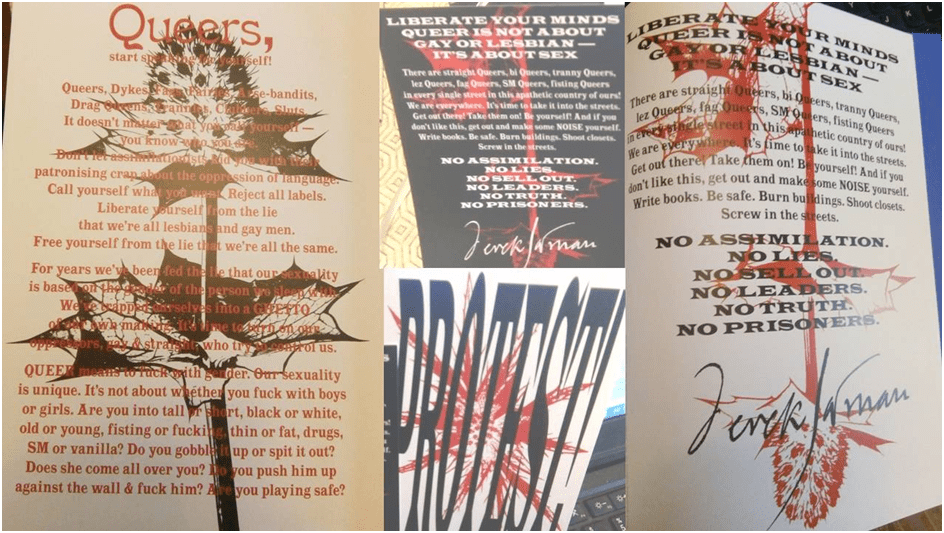

Liberate yourself from the lie that we’re all lesbians and gay men. Free yourself from the lie we’re all the same.

For years we’ve been fed the lie that our sexuality is based on the person we sleep with. We’ve trapped ourselves into a GHETTO of our own making. It’s time to turn on our oppressors, gay & straight, who try to control us.[2]

I don’t think Justin necessarily shares those ideas with me – neither does Geoff – but they both tolerate my beliefs. Jarman defined it clearly in the brash style of a manifesto and those definitions can be – and here commodity fetishism still rules – purchased in the gallery as postcards, tea-towels, and posters.[3] It is worth citing these in an accessible form such as the page-size reproductions of these works in afterpieces of the exhibition book:

For me Jarman reinterprets traditions I am ambivalent about in classic and classical art, especially but not only the literary forms thereof, imposed on me by an education into values a long way distant from my working class origins. And for Geoff it was a mix of an imposed history of education as a Protestant in a Catholic school and a later absorption into a kind of Situationist anarchism in Leicester as a young man and gay activist. I found that I began to integrate Justin’s particular take, as expressed in his comments, just as I had already long absorbed his from my husband (of near forty years), even though as George Eliot says, for each of us and in each case of true listening and absorption from another, the ‘lights and shadows must always fall with a certain difference’.[5]

But challenged to say why this exhibition so stimulated very different minds and hearts with different historical and ontological experiences – like Justin, Geoff and me – I would guess that it is because we all in our own ways love the ways it challenges established historical traditions that are enshrined in images to which we are all, for different reasons perhaps, deeply ambivalent emotionally, intellectually and ‘spiritually’. This ambivalence applies too to the concept of the oneness of all arts proposed by Jarman, including those arts consisting of language alone or with the ritual action of bodies and communion with spirit in drama, religious ritual and dance. These forms of human expression from tradition, ever-shifting no doubt in their meaning as to with the social and cultural function they play, are revolutionised as ‘Protest’ by Jarman, and this is why I highlight Olivia Laing’s take on Jarman’s use of Wittgenstein that I cite in my title.

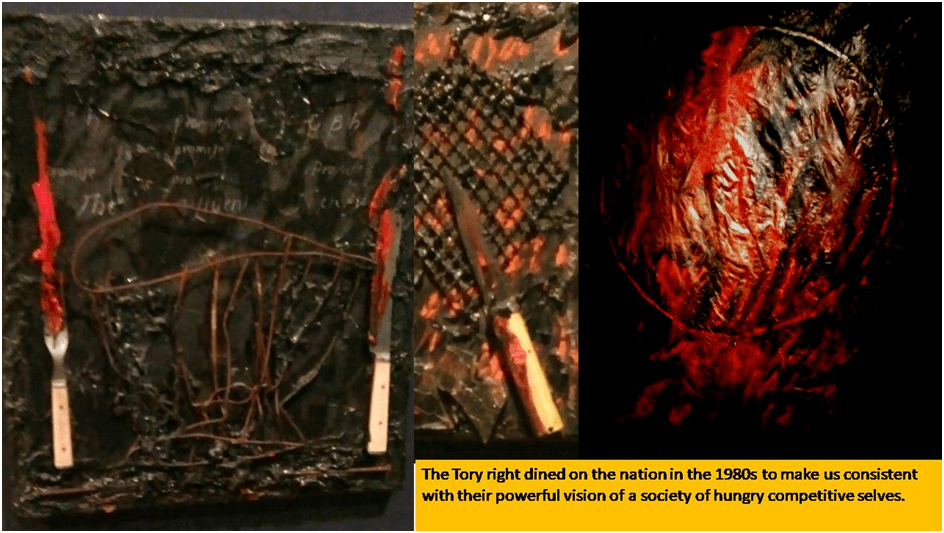

I think Laing makes it clear that Jarman starts not from a singular ‘understanding’ of what Wittgenstein was saying but from the contradictions between what he says and how he enacted life as a person. Some commentators take one of the most famous sentences in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus as a statement of the limitation of truth to what is publicly communicable: ‘What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence’. But, as Laing shows (talking particularly of the 1993 film Blue) this could equally be, and in Jarman’s hands definitely is, a protest at the silencing and cancellation of words, images and actions that fail to get heard, seen and/or otherwise sensed by the body in public. Hence the importance of art that obliterates one or other of these mediums or brings it into a thing that can appear that which life is not, which is plain, singular and simply coherent rather than fantastical, plural and complexly incoherent. This is half-grasped too in The Guardian’s review of this show by the admirable Adrian Searle: the key statement of which is ‘Coherence is overrated’.[4] After all Margaret Thatcher turned politics into GBH (Great British Horror and Grievous Bodily Harm both referenced in the painting) and transformed the ways our blood flowed to models taken from her own neo-conservative self-concept when she took us not to lunch but for lunch, as one of Jarman’s wonderful Jubilee paintings show. Justin will recognise his political analysis of the decline to the feral in contemporary politics here.

The necessity of diverse response must be true too in terms of the individual differences viewers bring to art when they are truly engaged. For instance, again for Justin I think this show animated and reinterpreted the traditions that speak through having grown up in Catholicism as a culture, not the same of course as growing up in an unswerving belief, as Jarman’s own background also suggests and a context in which retributive power often embodied itself in painful forms, sometimes reluctantly learned.

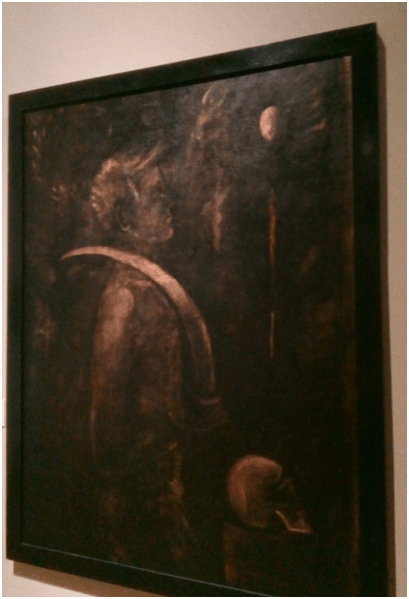

Let’s take for instance the darkly obscure and ‘obscured’ pictures that Philip Hoare references in the exhibition catalogue, with a glance at Van Gogh of course, as a ‘Tarry, Tarry Night’:[6] sometimes called the ‘Black Paintings’ or, by Olivia Laing, ‘’tar paintings … made in the late 1980s and early 1990s’. They are described as an ultimate silencing and cancellation of the sense and other effects of words, objects and images: ‘To make them Jarman boiled up tar over driftwood bonfires on the beach outside his house in Dungeness. He ladled it over canvases, immersing a wide range of objects’.[7] It is not good enough to say that this represents alone the silencing of the crisis in the lives of men who had sex with men and many others marginalised cultural groups. In those latter instances lives lived with the virus were even more silenced that for gay men. These lives included those of women, and those from areas of poverty and relative educational deprivation that was sustained by a privileged few (both in terms of nations and oligarchic power structures within nations). Everything and everyone who linked this disease to real lives and not to myths were obliterated from the public record by ignorance and, essentially, a lack of interest in these groups. But this phenomenon was in itself part of a much wider annihilation of the margins by the centre. It occurred not just by submersion and silence of marginalised voices but by covering them up with the eternal talk of the paramount value of the norm; often passing itself as ethical and cultural discourse.

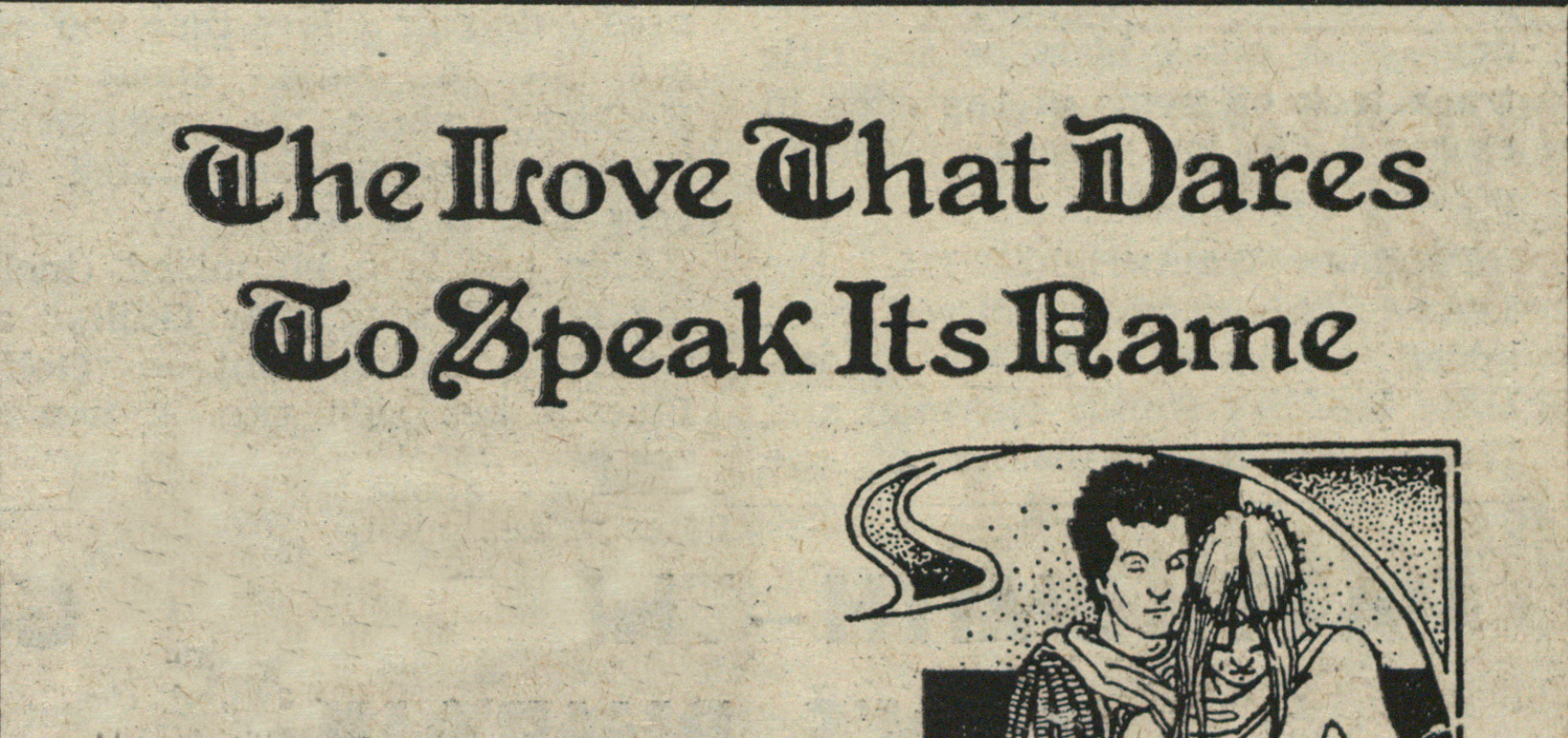

There were extreme examples. One is discussed by Adrian Searle. The collage work ( a kind of bricolage) named I.N.R.I. is only partially articulated in effects created by ladled tar. Much more is going on here. It is brilliantly discussed by Seán Kissane, by referencing the trial for ‘libellous blasphemy’ against Gay News for publishing a poem by James Kirkup The Love That Dares To Speak its Name – with its implication that Jesus Christ could have had sex with other men – and the later passage of Section 28 of the Local Government Bill. The latter enforced action by local authorities on those, teachers, publishers and artists alike, whom ‘intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality’.[8]

How are we to read this without confronting a troubling suspicion that, as Seán Kissane says, its composition is an example of ‘sheer madness’?[9] This is a collage (very acutely too a cultural bricolage) in which images that are normatively gendered are cut off from any serious context in which gender dominates the determination of behaviours – such as squashed beer cans, rusty implements that are or pretend to be implements of work but all out of relative scale with each other. The plastic figures have a context but it is a radically queered one in that the figures from the Masters of the Universe franchise are used so unconventionally – there are two Skeletors, whose fearsome appearance is being displaced by what appears to be their enacted play, as children play, of strong man games with outsize chains. Their colleague, He-Man, is like them ‘uber-macho, muscle-bound fantasy’ version of a male stereotype but whilst the Skeletors play on a lower register, He-Man is bound (literally chained and bound with hard wire) in an homoerotic embrace of Christ on a Cross bearing the legend I.N.R.I.. In this respect he represents too, if metaphorically, the manly centurion in the Kirkup poem as the latter reflects on his part in the Crucifixion while bound to his role as torturer.

The same ambivalence Jarman also explored in the role of Lightborn (or ‘bastard’) in his free filmed version of Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II, where the sadistic torturer of gay men yet again turns into a lover. With the right cultural background we realise, helped by Kissane in my case if not Justin’s, that the apparent work implements are also the Arma Christi, the ‘instruments of the Passion’. What emerges is something often more silenced than blasphemy, the notion that masculine activity, including violence and aggression, is a kind of bondage to the desire for Passion over Action, passivity over physical work.

To be queer is not to escape the complex make-up of sex but to embody it in real but non-normative form. There is nothing that pretends to moral superiority to human sex in the term queer as there is so often in the way the current LGB movement, for instance, naively uses the terms lesbian or gay as moral neutrals: perhaps then ensuring that oppression continues to occur unnoticed in non-normative situations such as in the case of women who are perpetrators of domestic violence, and violence of that same kind in lesbian and gay relationships. Of course these latter examples are a minority of lesbian and gay people and women but not therefore insignificant as that blinkered movement pretends. They are part of a diversity that is not just an innocent variation but about the constituents of that thing we call ‘sex’, including power, which make up its complex formulation of differing behaviour. It is not just defined by ‘whether you fuck with boys or girls’, as Jarman says.[10]

There is not just some glib statement underlying INRI that male violence, especially violence between males, has a repressed sexual content but that, in reality sex for some people is linked to inflicting pain and recognition of their own power. Even gay male contexts can suppress such knowledge – that gay men, for instance, are not in kind different from heterosexual men in the expression of their sex and sexuality but often very much doubles of each other in a range of behaviours. Hence the beauty of that heart made by a link of faux pearls, transfixed by a phallic nail – possibly a nail of the Holy Cross, that strikes through it in the manner of a heart impaled by Cupid’s arrow.

In a similar way (and it was Justin who saw this for me in his conversation with Geoff) classical masculine poses and representations of the classical-in-action in art, becomes confused to stop us idealizing, or ritually ‘sacramentalising’our response to them in conformity with the elitists. We just have to recognise in these paintings that our view of male suffering and strain, in religious or aesthetic passion, is sexy. It is in fact I think only not recognised as that because we wish to conform to the norms of powerful elites and oligarchies. We see this in the films too – in Sebastiane as well as various call-outs out of Christ’s crucifixion in other films and painting in religious contexts but elsewhere in parodies of ‘high’ or ‘fine’ art.

Sometimes the games played by the artworks in the area of symbolic iconography, like that Pythagorean or alchemical egg obscured in the painting below, cannot be easily interpreted so insistent is the desire to emphasise sensuous and sensual deprivation – silence, darkness or cover. But then neither can that egg when it appears in a work by Piero de la Francesco.

One particularly strong element of this show is the insistence on the continuity and fluidity of time in contemplating changes in Jarman’s self-representation in time. This does not reflect any silliness about consistency of belief but rather the attempt to always make old experience relevant to new input from the processes we often deny power such as growth but also age, sickness or death. The nineteen year-old pictured in the collage below with his first self-portrait declares the aim to represent self openly. But time did not just move on for him up to his death in 1952 from an AIDS-related illness by, as it does for many, by parcelling up and storing the past out of sight. He refused to boundary his experience allowing early experience to merge with all its associations with later experience – planned or contingent. Thus the past and its associations attempt to work with the totally contradictory ones from different times and places, new or old as they are discovered through life.

Some meanings get erased in the process but not necessarily lost – this is why I think Olivia Laing calls his work an intentional rather than accidental recreation of the method of the palimpsest. Searle puts it well:

The variety of his approaches, and the shuttle between introspection and outrage, and the radical shifts in his tempo and method over the 40 or so years of his career don’t make life easy either for his curators or viewers. There’s too much to take in, …

I would say that it is just ‘too much to take in’ and process for one person alone and that is why I would advise you do not visit isolated from other views but together with people you love and respect as we did. For in their non-matching angularity of difference, people with their inborn and acquired differences will emphasise to each other participant that looking for a coherent narrative in Jarman’s (or one’s own) life is a kind of wishful thinking and fantasising: false. We love each other’s differences because we would (or should) love the discontinuities of self demonstrated in our own lives rather than the fictive ‘consistent’ self our oppressively normative society always asks us to be. Else we really die. That is why Jarman could even see himself as a collage of the medications that in early times were necessary to halt the transformations that enable HIV positive status to be identified as the various opportunistic illnesses it facilitated but was not itself.

Jarman could incorporate into his self-image even ambivalent irrational anger, turning at one point to identify with the right wing curmudgeonly character of Wyndham Lewis for instance. So why not become a saint, as he frequently enacted, to the nuns of the ‘Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence’ or work as if he were Matisse or David Hockney. Visit the show with people you love but make sure you respect their different kind of uniqueness from your own with its own concatenation of influence and complex relationships to their own biographical changes. These are not just differences in biology but also in determinant social, cultural and psycho-geographical influences. Because to be queer is to have open boundaries that only become meaningful by being crossed and transformed. It is not to be defined by gender or sexual orientation – either that you own as yours or of the persons with whom you have sex.

All the best,

Steve

[1] Olivia Laing (2020: 255) ‘Language Games: The World Is Everything That Is The Case’ in Seán Kissane & Karim Rehmann-White (Eds.) Derek Jarman: Protest Dublin & London, Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) and Thames & Hudson Ltd. 252 – 257.

[2] ‘Queers’ in the Afterpieces (ibid: c.318)

[3] Such is the downside of the queer world as it enters a market economy, but that itself is an aspect that Jarman himself predicted and took into account in his definition, much in line with the Situationist movement in Europe that inspired some parts of the Paris Spring of May 1968 (see link to a blog of notes on an essential book on the matter) and the psychogeographers in London associated with Iain Sinclair.

[4] Adrian Searle (2021) Derek Jarman: Protest! Manchester Art Gallery Review – ‘Coherence is overrated’ in The Guardian Mon 6 Dec 2021 17.43 GMT. Available at: Derek Jarman: Protest! review – ‘Coherence is overrated’ | Art | The Guardian

[5] “We are all of us born in moral stupidity, taking the world as an udder to feed our supreme selves: Dorothea had early begun to emerge from that stupidity, but yet it had been easier to her to imagine how she would devote herself to Mr. Casaubon, and become wise and strong in his strength and wisdom, than to conceive with that distinctness which is no longer reflection but feeling-an idea wrought back to the directness of sense, like the solidity of objects – that he had an equivalent centre of self, whence the lights and shadows must always fall with a certain difference”. Book 2, Ch. 21 Middlemarch. Available at: Middlemarch by George Eliot: Chapter 21 (online-literature.com)

[6] Philip Hoare (2020) ‘Tarry, Tarry night: The Queer Nature of Derek Jarman’ in Seán Kissane & Karim Rehmann-White (Eds.) op.cit.: 284 – 295.

[7] Laing op. cit.: 256

[8] All cited by Seán Kissane (2021: 56) ‘Irresistible grace: Tracing Alchemy, existentialism and literature Across Three Decades of Painting’ in ibid: 18 – 77.

[9] Ibid: 55

[10] ‘Queers’ in the Afterpieces (ibid: c.318)

7 thoughts on ““If the paintings are palimpsests, the books are reliquaries, filled with asynchronous wonders … preferring to animate old revels by injecting them with a chaotic modern element”. How and why the art of Derek Jarman defies time as we think we know it to be and as we think we know it works. This blog reflects on Seán Kissane & Karim Rehmann-White (Eds.) ‘Derek Jarman: Protest’”