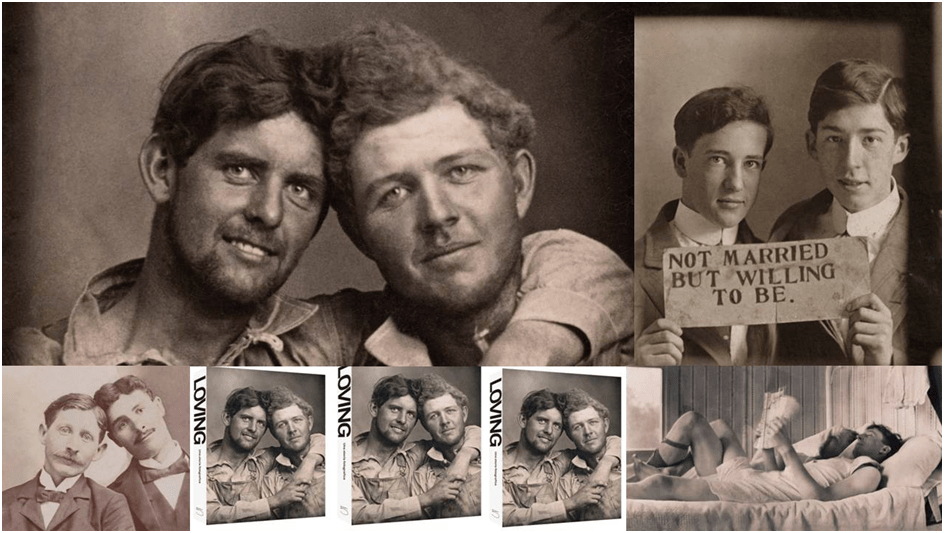

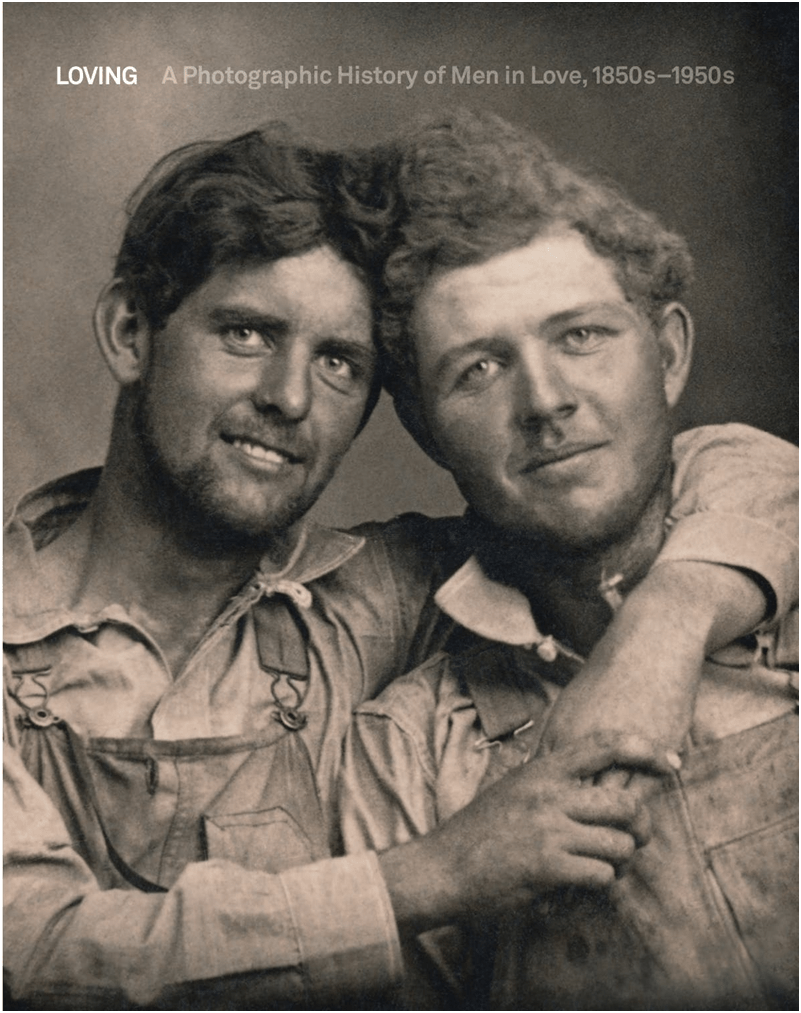

This blog uses examples of artworks but is in fact really about how the confused mess of discourse surrounding how the meaning of pictures that focus their gaze upon men is named and/or interpreted. It refers also to the selection from the Nini-Treadwell photographic collection in that beautiful book of wanton over-naming and over-interpretation (which I thoroughly applaud by the way) published in October 2020: Paolo Maria Noseda, Hugh Nini & Neal Treadwell (2020) Loving: A Photographic History of Men in Love 1850s – 1950s Milan, 5 Continents Editions.

Naming and interpreting are both actions of the mind and body (whether performed through the voice or hand or internally apparently without either voice, hand or other organ intervening) that in practice cannot be independent of each other. Some intellectual traditions have for too long pretended that they can: that words can be disambiguated and made to stand for one thing or action or even autonomous signifier, that is a thing and/or action in language alone. These words are prime examples of words that can only be used in the context of each other and other contextual signs.

Since queer theory first emerged, and perhaps before that, there has been a problem about naming pictures of male bonding, haunted by fears that any name given to the observed relationship is an over or under interpretation of what we see – a conscious or less conscious ‘bias’ in naming that action. And I’d argue perhaps that is even more complicated when we intuit the male gaze as a third term in that relationship since that gaze is attributed with the power of interpretation, and possessive naming in feminist theory. It is into this complex network of interconnectivity between naming and interpretation that Andrew McMillan has just stepped in an essay on why he writes poetry, saying, of his first poetry collection physical: “… I’d argue the real subject was the male body. …: what if that male gaze was turned on other men – only partly in a homosexual way, but also in a homosocial way?”[1] In the same essay on why he writes poetry, McMillan says: ‘I didn’t actively choose to be a poet of the body, or queer male desire, or masculinity, or any of the other labels that are put onto my work’.[2]

The problem of naming and interpreting shouts out from this intervention as McMillan struggles with characterising the relations within the male gaze as observed or utilised in order to gaze; what, for instance, does it mean to gaze in a ‘homosocial’ as opposed to a ‘homosexual’ way. The analysis of the homosocial was complicated by queer theory, since it determined therein both a mechanism of male domination in a gendered society and a source of a softer bonding between men that is disguised by appearances of being sociable, with concepts like the ‘mate’, the ‘marra’ (in an example from the working class of the North East coalfields) and even ‘comrade’, with its range of meanings that politicise the personal in a kind of innocent way, in relation to the sexual or amative.[3] This is compounded by McMillan’s view that naming the subject-matter of his poetry to be ‘of the body, or queer male desire, or masculinity’ is just a ‘label’ imposed on it rather than a valid interpretation of its intention or aim. Of course the poet is not denying that these labels describe something that his poetry observes in himself or others, only that it was not his motivation for his poetry to be thus named. I have no observation about this, for I think it is merely illustrative of a problem – is it possible to observe, or even more ‘gaze’ at, the ‘male body without some intention indicative of either or both relationship or identity, or is to confuse the difference between ontology and epistemology (between what ‘is’ being seen with what we see ‘means’, even given the complexity of confusion and even contradiction of meanings possible).

I tried to enter this discursive web myself in commenting on Titian as part of a history of art course. My recourse to neologism – inventing a term I call ‘homosomatism’, is really a less reflective response to the messy problem in discourse I am trying to describe in this piece. Here is how I analyse, for instance, details from Titian’s Two Satyrs in a Landscape (1509 -19):

… the play of hair / fur (the naming announces the liminality of the beings caught between animal and human) merges not only bodies with grass but body with body. I do not sense though a sexual meaning (or as people with a preference for late nineteenth century medical terminology sometimes prefer to call it ‘homosexual meaning’). If anything this is as near as the ‘play’ (to take Whistler’s term again) of light and bodies but also of bodies. What this picture ‘means’ to me is that it makes apparent visually an asexual comfortableness of the male body with body itself and the body of other males.[4]

As I reflect on this now, I see the same problem in what I do that was raised for me in Andrew McMillan’s essay: queer people have so long been victim to labelling (notably by the medical term ‘homosexual’) that the issue of what is sexual and what is not in male relationships is made problematic. We seek other labels in order to illustrate that our experience of the world of men in which we live is a complex thing, where different varieties of response to other men’s bodies are experience but somehow cut out of the stories society tells about the substance of our lives. Key to this is our relation to pictures of male closeness. Recently I came across Hans von Aachen’s painting of ‘Two Men Laughing’, which has, or so it seems to me, some relevance here.

The more our gaze is invited, I would argue, the more we intuit a relationship between the men which is an emotional bond. Even if we try to disembody the meaning of the bond, deciding that this is how males can bear some closeness to each other precisely because neither believes that proximity to be at all sexual, we cannot eradicate the need to distinguish sex from other forms of inter-relationship, making it seem a means of debasing or devaluing male bonding that can be considered normative. We hesitate therefore to label it as akin to something queer in our society, a relation that goes under-reported and under-examined by its participants, the more to be able to fly under the radar of our sense of what passes for ‘normal’.

When Hugh Nini and Neal Treadwell started collecting photographs of male ‘couples’ who were in love with each, they had no evidence that this was the case except for one where a nephew knew his uncle was ‘closeted and gay’.[6] Hence they determined whether or not the photographs were appropriate for the collection’s themes – of loving male couple – by body language patterns and even social contexts that they believed to cross the different conventions of what is considered normal homosociality in different cultures and periods because they were derived from the ‘common humanity’ of the men therein. One of the most contentious ‘proofs’ of a loving couple used by Nini and Treadwell is also of much relevance to us, for the find it in the manner of ‘gaze’ of the couple, and not just their ‘gaze’ at each other: ‘Whether to the viewer, to one another, or averted, [the gaze] always conveys the kind of romantic love that everyone knows about and is singular and special’.[7] This will seem inevitably subjective and subject to differences in display conventions for men that are deeply situated in history and culture – varying across time and space. But one thing is definite, the criteria for identifying romantic love is seen as independent of sexuality and the range of sexual orientations to different categories of targets of that love.

My issue in reading both Andrew McMillan’s recent essay and indeed my own earlier blog, though I don’t equate these by merely comparing them, is that even those of us who fully identify as queer in public sometimes seem nervous of finding words that characterise our difference in either terms of either sex (either as an identity marker or activity), gender or sexual orientation terms. For instance, when McMillan talks about the gaze on male bodies – alone or in interaction – he says (to remind you) that it might be ‘turned on other men – only partly in a homosexual way, but also in a homosocial way’. I struggle to understand this fully, partly because of the charged meanings of the term male gaze in feminist theory, which describe the strategies by which representations of women are sexualised. The problem with the representations of men is the resistance to their sexualisation, and, in a sense McMillan does this here, as do I in inventing the neologism homosomatism. How can the male gaze that sees men in a homosocial way be any different from that is often used to deny the sexual content of pictures of them, especially (but not exclusively) in the nineteenth century.

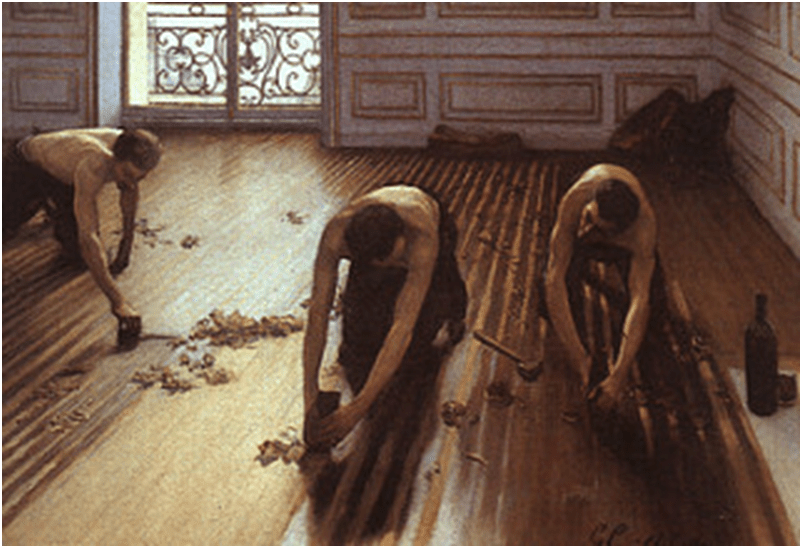

Consider, for instance, this issue in relation to works by Gustave Caillebotte in an earlier blog of mine. The view I express is no doubt an oversimplified characterisation if the rude note I received from the art historian I critique is to be credited. I am not sure however, even now, that I don’t stand by what I see as a fair attempt to describe his argument, even if antagonistic. This section looks at Michael Marrinan’s discussion of The Floor-Scrapers of 1848. Here is a part of my commentary. It starts after showing how Marrinan asks us to attend not to the male torsos but the spaces between them, which he sees as paramount in interpreting the painting. I say:

We are also shown how distant are the bodies of the painters from the classical ideal that Winckelmann associated with the perfected style of the nude. They are described as undeveloped bodies, clearly those of working-class men, quite unlike the classical ideal appearing in the statuette of a male nude that appears in Caillebotte’s Interior of a Studio with Stove (1872): of course Caillebotte’s own artistic studio. This ‘evidence’ is used to show that there is no sexual charge to the gaze of the artist or viewer possible in this painting.

My blog challenges this reading precisely because I see this removal of the sexual from notions of the male gaze on men in favour of the homosocial – men at work – has some resemblance to the problem I am trying to describe. The same can be said more specifically of work on Renaissance male nudes, although there focused on a specifically named sexual act – ‘sodomy’. I think the resistance of seeing the male gaze on male relationships has a similar problem, even though the word ‘sodomy’ clearly has its own issues for the art historian cited here. I address in yet another earlier blog Patricia Rubin’s critique of Michael Rocke’s discussion of Passignano’s Bathers at San Niccolo. Rubin contradicts Rocke’s use of the painting to instance the open acceptance of male queer relationships in Florence, and says: ‘… it is not about sodomy or sexual acts’ but ‘a vista of healthy, naked or nearly naked men, mostly young, enjoying physical activity’.[8]

I don’t intend to argue Rocke’s case here but just to point at how a ‘male gaze’ on male interaction is yet again radically desexualised. I think what I do with the Titian drawing uses similar strategies to Rubin’s, but still find more to support my desexualisation argument there than I find in Rubin’s reduction of the sexual gaze on men in the Passignano painting.

Nothing in this is meant to criticise Andrew McMillan’s position on why he writes poems but it registers my slight disturbance on seeing such a potential spokesperson for queer experience, across the widest range of experience through which sex is a mere strand, that he says (as I cited already above) ‘I didn’t actively choose to be a poet of the body, or queer male desire, or masculinity, or any of the other labels that are put onto my work’. I do not doubt the integrity of this but rather believe that we need to focus on the fact that that the nature of ‘choice’ is the problematic issue here, whether we refer directly to our sexuality or our writing upon it. One thing is crystal clear: the choice was not to write about these issues or not but to choose to face readers’ receptions of an issue so often misunderstood in ways that refect negatively on the person or writer – as being merely fashionable, writing for a limited audience and ignoring the complexities of life. For Andrew McMillan never does this, even when writing about his own mental health and that of queer men. I tried to say so in my last blog on his last superb collection in which our sexual lives become precisely a thread in a complex pattern or rhizome structure, like Knotweed, the focus of a set of poems in the collection:

The thing that holds this collection together is the moral territory on which it has been forced to reorder the emotions of life, and in this case specific queer lives that intersect with other lives through other bonds, like those of biological as well as chosen family and communities, even those of ‘neighbours’ to whom we contingently relate. The boundaries of responsibility that we hold for each other are examined in and through these diverse networks. And it is in these networks that the attribution of guilt and the growth of suspicions of each other occur in all communities,[9]

Hence my issue with Andrew’s self-characterisation as a poet is a matter of nuance not disagreement. I think in practice we all know the difficult choices McMillan has had to make to thread the sexual lives of men, including his own, on which he gazes and asks us too also, in a much richer pattern that should be used nevertheless to overshadow issues of sex, sexual orientation, gender and the rest – queer issues.

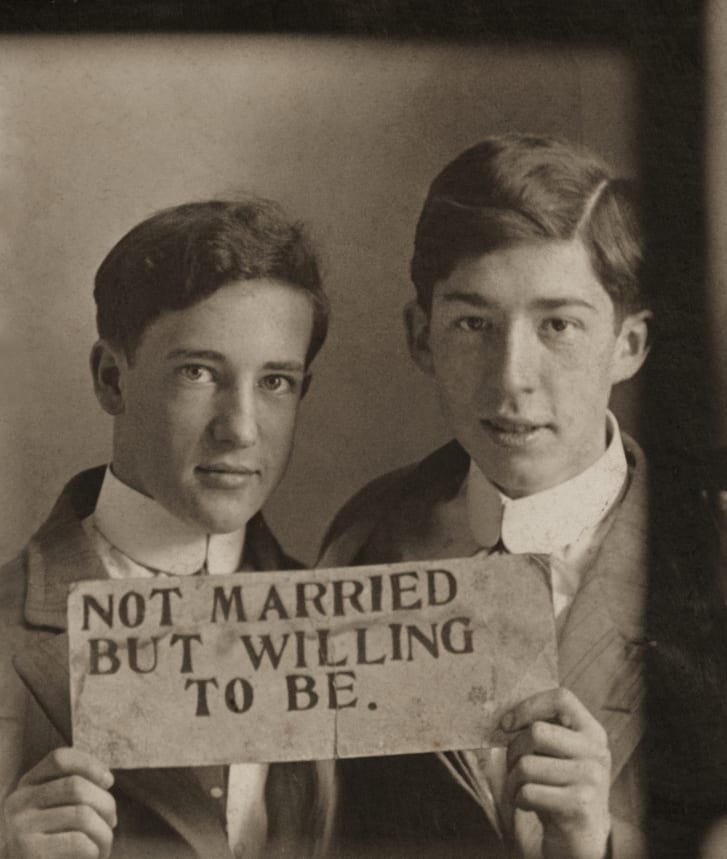

The interpretation of Nini-Treadwell collection of pictures, on the other hand, could be totally subsumed by eliminating all account of the difference from the heteronormative that they must also represent, whatever the stress in the writing in the volume on universals and human constants in acts such as an ‘embrace’ between two people.[10] The collectors say quite openly: ‘feelings of love, attachment or longing between people are the same – regardless of the gender make-up of the couple’.[11] This I can’t accept nor do I think that this is the lesson taught by the couple’s collection and the means by which it was amassed. I can only say why by commenting on some of the photographs this wonderful book selects from an even more wonderful collection by two pioneering queer collectors. Three come from a strip of 5 containing a pretended marriage, a marriage with a friend in priestly role by two teenagers and married together under an umbrella. the one of the ‘ceremony’ itself is mock playful – served by poses and expressions imitative of the most heteronormative of weddings.[12] However, the one which stands out is represented below. This photograph serves a number of functions. One rather questions the thesis of Nini and Treadwell. The message tells us that this marriage was not real but enacted. It refuses therefore precisely the kind of universalising readings about the source of loving gestures and expressions in a ‘common humanity’, rather suggesting, on the other hand that these enacted rituals are social in origin and authorised in some way in order to be legitimate.

What these young men show as they gaze at their viewers is a kind of open defiance, of any norms such as the ‘common humanity’ ones that might be asserting themselves and insisting that the refusal of their will to marriage is being forbidden by those very viewers, cast into the normative role as at least one of their subjective viewing positions in this picture, in front of them . If anything, their direct return of the viewer’s gaze is not, i think, speaking of their love for each other but insisting that the viewer does not know how to see their union of minds, hearts and bodies – has no model by which to interpret what they nevertheless see. The excessively repressive clothing – probably typical of that of grooms in a formal marriage of the time cannot repress the fact that the men otherwise maximise the fact of their visible bodies. Large hands with stubby fingernails (far from elegant or manicure in the case of the man on the viewer’s right) overshadowed by young fresh faces which laugh as if history of the future was to be theirs with or without the viewer, like the men in Von Aachen’s painting. The sensuality of the lips of these young men strikes precisely because one smiles with a closed mouth, the other showing a mouth that opens in speech or in response to a kiss from the other. If anything, the photograph says: ‘we are not you and you are denying our common humanity though our sexuality will out whatever your response’, though in relative privacy. The issue is that that the viewer cannot name them, not and really know them. What else have we left then but labels about variations of sexuality, sex and gender? That is our subject. We inevitably choose either to live these and to write of them OR to deny them and enact the available conventions and scripts. Here is where I differ from Andrew McMillan, if that matters.

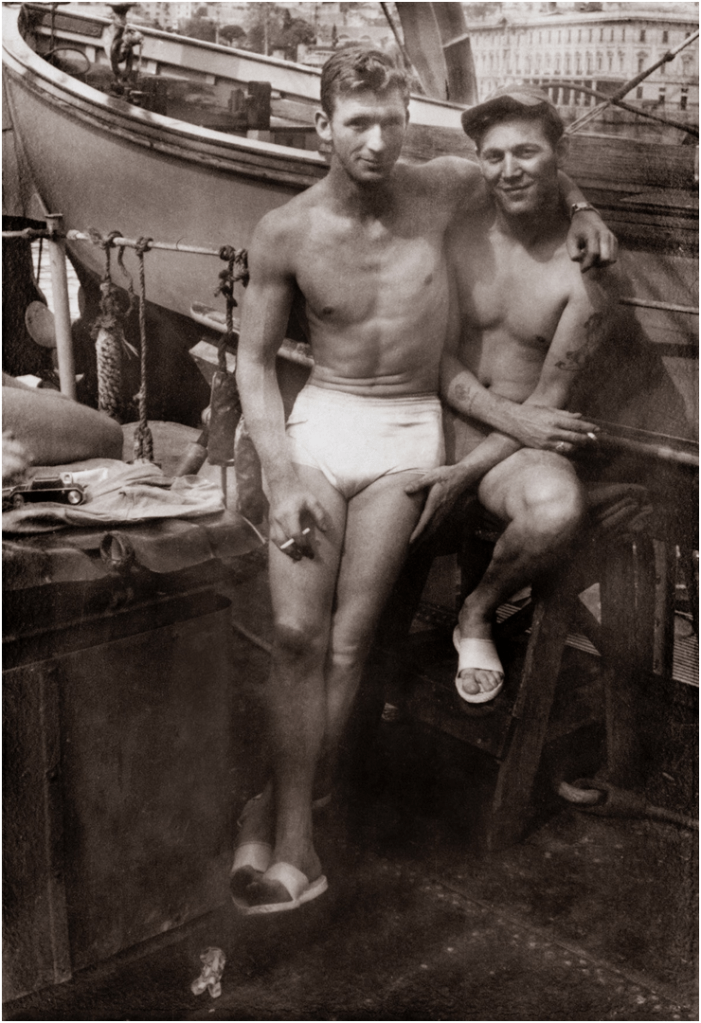

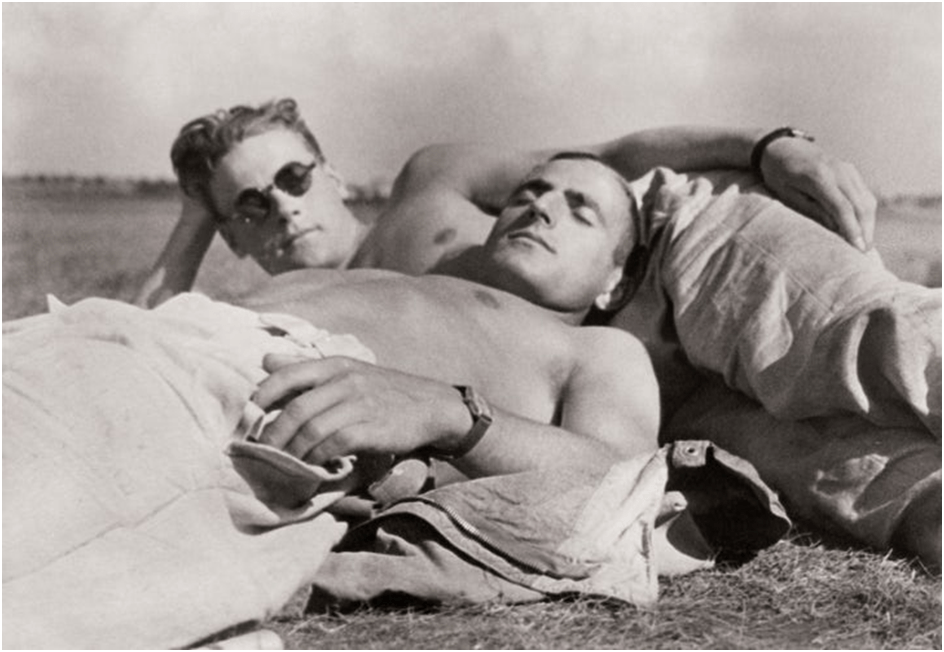

In fact, looking through LOOKING is to find many gestures, especially but not only those which show the full length of the bodies, which are not those heteronormative romantic love. The viewer’s gaze is drawn ineluctably to the sense of a visceral touch of bodies that are like each other and seen to be on the verge of merging or in some way becoming intertwined. This is clearer where the body parts that touch are unclothed or semi-clothed.

In the one above, the legs of the men seem to merge in order to emphasise likeness of body, despite the difference of clothing and clothing accessories. It is not a sexual scene in that the photograph is blurred on the ‘Adventure’ comic at its centre and on which they focus, because its pages are being turned or moved at the time of the photograph’s making. There is a whole history of masculinity implied here, not least in the sharing of ‘Adventure’ stories by boys, such that the relaxed intertwinement of the bodies feels both asexual and pre- or post-sexual, without any focus on genital sexuality implied or relevant. But it is not heteronormative ‘romantic love’ but a version of closeness, queered by the common maleness and, to use, my own word, homosomatism, used as its central interest. In the next, the two men bring attention to each as potentially sexual beings but in a very relaxed way that is absorbed in the mutual smoking of cigarettes, although this is miles from a Now Voyager moment.

The entwinement of bodies is sculpted such that the photograph centres on the clothed genital area at the standing man. The two men draw each other into that focus, aligning, in doing so, their torsos in ways that emphasise body likeness, which is emphasised by the male associated working implements which surround and contextualise their leisure and time out from working lives. Again the man in front seems to be merging by sinking into the body of the other. Differences in body hair and muscle quantities and their distribution, especially that drawn to our attention by a tattoo, do seem to enable a potential enactment of difference of sexual roles but that is subsumed by their relaxation of likeness. It shares some qualities with the Titian we looked at before.

Again in the photograph above the faces align horizontally across the picture with the groin of the man at the rear, but there is clear continuity between the naked parts of both bodies that again seem to be joined, as if one could merge, by sinking, into the other. There is an inevitable alignment conceptually and sensually I would say in all these semi-clothed pictures with a potential sexuality that is not solely ‘romantic’ in a heteronormative manner. Body likeness becomes the agent of body mergence and that is never the case in heteronormativity. In other pictures body likeness is signified by uncanny likeness of clothing, as with the farming ‘overalls’ below for the photograph also used for the book cover.

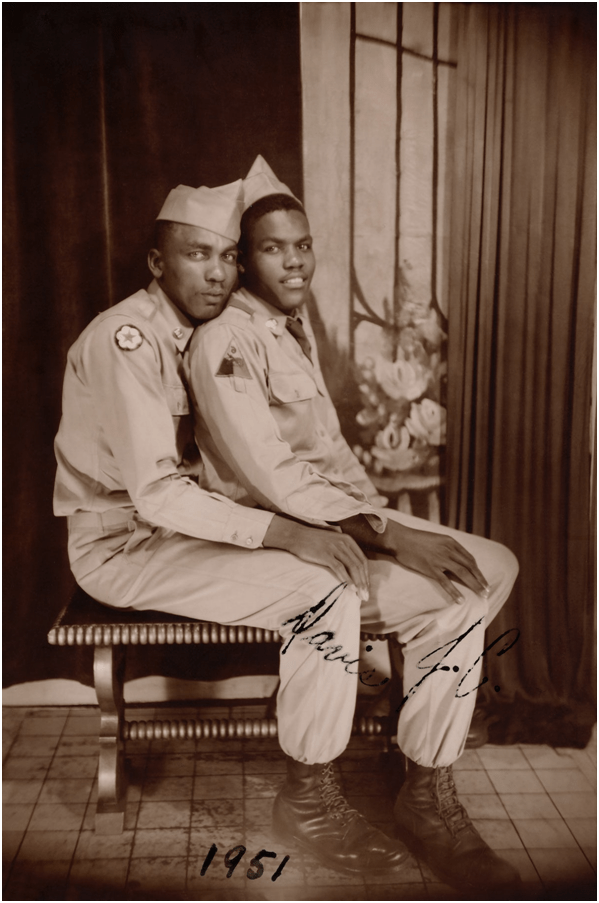

Many photographs exemplify this because the likeness of the men is brought about by accidental co-location in the forces, where significantly both wear a ‘uniform’. The name ‘uniform’ itself makes my point. The collectors comment on, for instance, the accidental co-location of men in the Austrian Alps in World War II, including the only one for whom identity as a Texan man who was ‘gay and closeted’ who could be identified, as John W. Moore.[13] Sometimes these uniformed pairs are as near as you can get to heteronormatively tolerated ‘buddy-shots’ (if not the last mentioned) and this is where the collectors admit to the subjective nature of their determination that nevertheless speaks when the viewer, ‘looks into’ the photographic subjects’ eyes.

Perhaps the best ‘uniformed’ body mergence shot is a comparatively rarer picture of persons of colour in uniform from 1951. As Nini and Treadwell have said in an interview with LGBTQ Nation only 20 of their 3000 romantic couples were ‘African American couples’.[14] In this lovely photograph of servicemen there is not only mergence through sinking of bodies, there is also a kind of mirroring of the pair of each other that further emphasises continuity of one body with another. This is the case despite the apparent difference of build, age and facial features. The uniform is doing a lot of work here but doing it – of that I have no doubt.

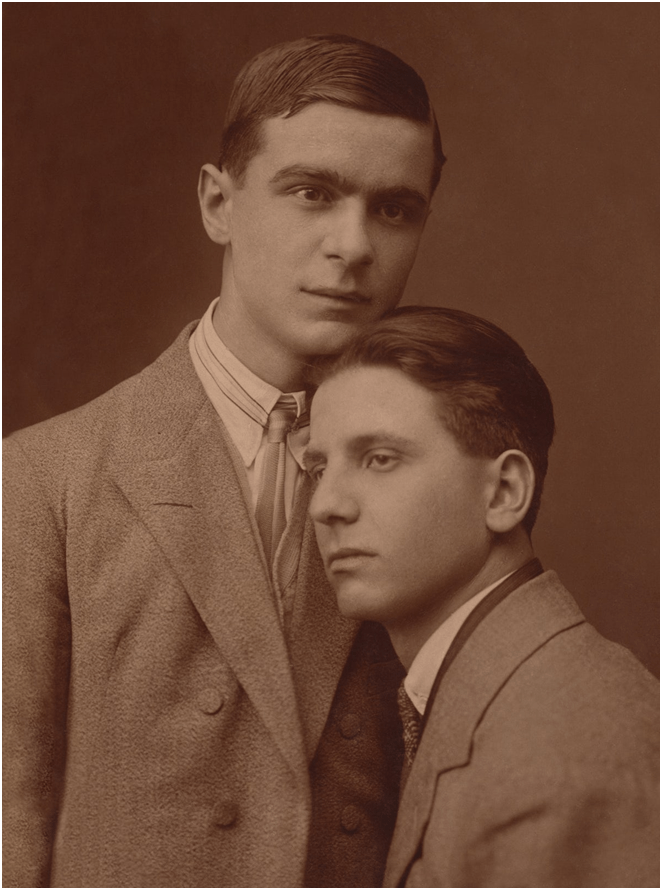

However in detetrmining whether this is a queer couple from a photograph alone, we are, of course, on contentious ground. Of those I looked through I felt more certain that those were more than ‘buddy-shots’ only when body mergence of some kind showed, such as a head resting on another’s shoulder, head or cheek, as below. Although below the eyes capture the gaze of the viewer in a way that encloses both men in a presumption of great proximity, it is the delicate and non-normative vertical alignment of faces that speaks to me. The men are still in a kind of uniform clothing with suits in the same tone and neck scarves but it is the fact of two heads in relation to one shoulder that merges them.

I cannot be sure that I have established that it would be wrong to eschew the intention to be, or to write, things that can end up in being labelled as “a poet of the body, or queer male desire, or masculinity”. In my view perhaps these labels ought to be embraced in part at least, Moreover, I’d also question whether when “the male gaze is turned on other men” we gain very little by isolating the homosocial from the homosexual, as if we had a choice of how we perceive the difference based on the appropriateness of the object gazed upon. For ‘looking’ is never innocent of sexuality, body politics and gender diversity issues, nor is the social an arena free of the play of sexual determination. There is no ‘romantic’ separate from sex or I’d say vice-versa since to be romantic is just to adduce a story of interconnection in which sex was once, will be or, without or knowing, is already sexual. We just have to be clear that the latter is the not the hegemonic tool of our relational readings.

All the best,

Steve

[1] Andrew McMillan (2021: 33) ‘The Body I Could Trust: On Writing and the Changing Voice’ in Ian Humphreys (Ed.) Why I Write Poetry: Essays on Becoming a Poet, Keeping Going and Advice for the Writing Life. Rugby, Nine Arches Press, pp. 31 – 36.

[2] Ibid: 34f.

[4] From my blog (cited passage slightly revised): Introducing Homo-somatism? The nature of ‘queer’ readings in Art. – Steve_Bamlett_blog (home.blog)

[5] Roland Recht, Catheline Périer-d’Ieteren, and Pascal Griener (Foreword by Peter Burke) [2007:323] The Great Workshop: Pathways of Art in Europe 5th – 18th Centuries europalia.europa Festival in Brussels, Europalia International, Brussels / Mercatorfonds, Brussels.

[6] Hugh Nini & Neal Treadwell (2020: 17) ‘An Accidental Collection’ in Paolo Maria Noseda, Hugh Nini & Neal Treadwell Loving: A Photographic History of Men in Love 1850s – 1950s Milan, 5 Continents Editions, pp. 14 – 23.

[7] Ibid: 22

[8] P.L. Rubin (2018: 109) Seen From Behind: Perspectives on the Male Body and Renaissance Art New Haven & London, Yale University Press

[9] For my blog see ‘SO WILL FALL // whose fault? / Paradise Lost Book 3’. [1] Whence queer poetry? Reflecting on Andrew McMillan (2021) ‘pandemonium’. Forgive misunderstandings and any gaucheness @AndrewPoetry – Steve_Bamlett_blog (home.blog) This blog was referred to others by me on Twitter.

[10] Paolo Maria Noseda (2020: 8) ‘Amante Amentes’ in Noseda et.al. op.cit., 8 -13

[11] Nini & Treadwell (op.cit.:18)

[12] Described ibid: 21f. Picture on pages 312f. & 88f.

[13] Ibid; 16f. (referring to top photograph on ibid;110)

[14] Cited in Nini & Treadwell (2020b.) ‘Historical photos of men in love: The rocking chair on the rooftop’ in LGBTQ Nation (Friday, October 2, 2020) about a photograph NOT in the book but very beautiful. Available: Historical photos of men in love: The rocking chair on the rooftop / LGBTQ Nation

4 thoughts on “This blog is about how the confused mess of discourse surrounding HOW the meaning of pictures that focus their gaze upon men is named and/or interpreted. It refers to Paolo Maria Noseda, Hugh Nini & Neal Treadwell (2020) ‘Loving: A Photographic History of Men in Love 1850s – 1950s’”