“… every lapse from the imaginative into the idées reçues” of orthodoxy is disappointing”.[1] Once upon a time there was a world where John Burnside’s statement about the nature of an artist’s writing set appropriate expectations for a reader. Has this time gone? This blog reflects on Burnside’s (2021) Aurochs and Auks: Essays on Mortality and Extinction Cornwall, Little Toller Books.

I have believed in the importance of John Burnside as a modern writer – in his novels, poetry, memoirs and other writings for a long time, although I have only blogged on him once before (see link). It strikes me now that we have missed seeing him in his full strength as a great social commentator and essayist – one who reminds me most of Carlyle and Ruskin, men with a vital social message and compelling means of delivering that message, so that it strikes home.

But that comparison matters less that the point I illustrate in my title: that Burnside has an almost apocalyptic view of a world too readily given up to retailers of idées reçues rather than original thinkers, and a strong sense that he, at least, must fight the tide of orthodoxy about to wash us into oblivion by its refusal to value the world or direct action in it, including writing directed at animating that action of mind and body. Hence, despite the urgency of its messages about the imminence of possible extinction of species, free space and time to think and reflect and indeed the mind itself, it is already also an elegy for what is lost already. That tone is perfectly captured by the ghostly images in the book and on its cover by Tim Robertson.

Elegiac about great animal species-prototypes of the meaning of extinction are also a taste of death that their loss brings to each of us individually, as we lose more and more to the enclosure of our physical and mental space and time to orthodox boundaries and borders of our access to a phenomenon Burnside calls ‘la vie commune’:

When I think of England gone, I think of a garden in the West Midlands, … /

… I will not describe the place further … because it is gone now, … I can go there in my mind’s eye, but when I do, i must prepare myself for a grief that, as much as it acknowledges other, associated losses … it cannot be divorced from that memory of that place. And that grief is private, which means it cannot be expressed as part of la vie commune.[2]

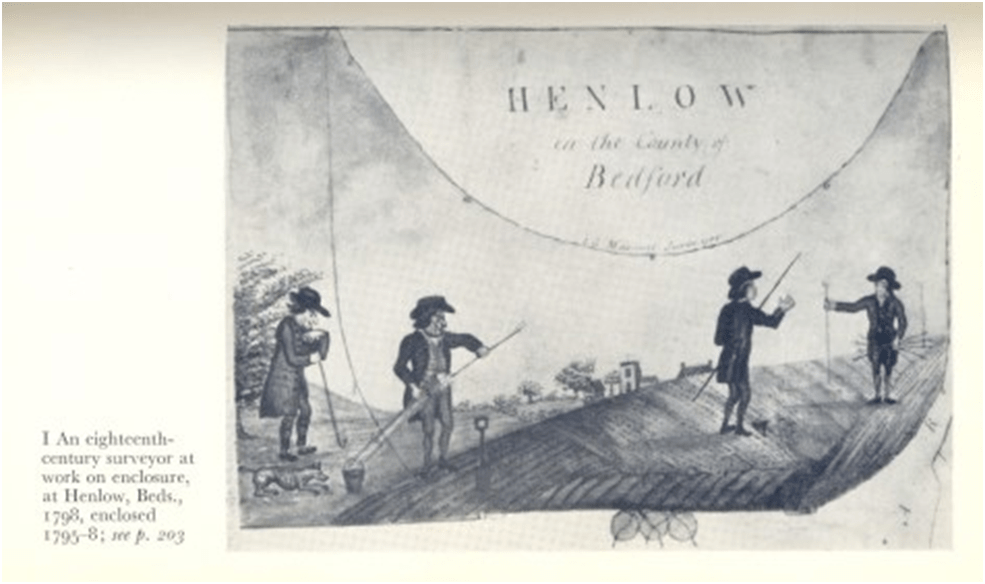

What is common to us all by necessity accepts that all of us will die in fact as individual persons, is ‘detached from individual concerns’, and finds the idea of space and time filled only with me, a prospect of which, ‘I could think of nothing worse’.[3] In that respect the beginnings of its loss were marked in the socio-cultural world by Rousseau’s attack on creating private properties from the unfenced land in 1762, the enclosure of common land for private use witnessed by John Clare and, finally,:

… the enclosure of experience itself – not only of our consumer tastes, but also of our root desires, our dreams, our political leanings – has become commonplace.[4]

Perhaps all this has now occurred or is occurring to the point of not being stoppable, since, as we see here the only ‘commonplace’ is not a free space but an enclosed one, with boundaries set by powerful others. The most moving example of this, in a book in which Burnside recounts his own near-death experience (NDE) from Covid-19 in this current pandemic, is the attempt by government to capture the thanks people felt to the NHS for saving their lives for their own purposes in a commonplace phrase, that is anyway a lie:

Nobody can say these people are as culpable as the CEOs and politicos who keep the extinction machinery running – they at least have chose to work on the side of life. This should not be forgotten. We are by no means all in this together – and we never were. I say this again: this should not be forgotten.[5]

Here I think we see a prose so reminiscent of the urgency of a religious mission, we can forget that what Burnside is pointing to is the iniquity of those who are in chief responsible for the maintenance of the machinery of extinction for their own minority interests and our duty to displace them.

The name of those people who order, direct and sometimes execute, or get executed for them sometimes by the victims of their greed, acts of enclosure of the common heritage of the 99% is not ‘legion’ (for this is not a supernatural but a political act): it is ‘developers’. For instance, though some nature park projects, including bat reserves, draw endangered species back in the common life, …

Developers of all kinds work hard to defuse its power, either by appropriating it for political purposes … or by dismissing every act of resistance to their version of Progress as pure sentimentality’.[6]

Developers develop everything in ways that translate those things or the things they work upon into malleable reductions of a complex world that they can then own. Burnside is correct to include in these, developers of psychotropic prescription drugs who, before they can make a profit, must colonise the mind, thinking, feeling and sensing as things only understandable as chemical processes that can be externally manipulated. Burnside however, who has confronted the psychiatric system himself, will:

… remain unpersuaded that the chemistry of the brain accounts entirely and conclusively for the life of the mind – a phenomenon that finds its full expression, not in an individual cerebellum, but out there, in the constant play of la vie commune.

There is a problem of course about what to call this space and time that no individual person nor oligarchy owns or controls, except that it can be sensed in the imaginative creation of stories or in the act of story-telling (in the native Australian concept of The Dreaming, for instance – but also in canonical stories that tell of storytelling by Charles Dickens and Herman Melville) and in the phrase ‘Once upon a time’:

… not just here or there, in this or that specific location, and not at any determined point in history, but in a world that is both proximate to this world and, at the same time, wholly other.[7]

It can be accessed only by the whole mind including the powers of subjective play: ‘Empathy, sympathy, connection of any kind, is mostly based on intuition, not destructive logic. Guesswork’.[8] In contrast the first developer was Cain, the brother of Abel whom Cain murdered. Hermann Göring was such another from a later age. In truth, freedom comes from acknowledging that we are all ‘Meat that thinks’ just as the cave painters at Lascaux are said to do do in common with a cow witnessed by Burnside who now knows she cannot rely on ‘the masters in whom she had placed such trust’. She too is ‘meat that thinks’. And so too is Burnside recovering from an episode of Covid-19 from which he was expected to die. Now we know religion may once have filled that space we cannot now describe. We know too that the world of ‘the post-Celtic idea of Faerie’ is a thin representation of it.[9] A better one is heightened vision and even hallucination and Burnside invokes Jung at this point.[10]

But most of all I think Burnside knows that urgent writing in any form is of no account if it fails to lead us by connection to others as well as the other and rejects authority which has housed itself in government, academic departments and invokes the ‘Authorized Version of How Things Are (… “The Real World”)’ since it belongs to them as resident ‘powers-that-be’, rejecting any ‘uncharted no-man’s land’.[11] And Burnside’s writing is more urgent than ever.

Read it please.

All the best, Steve

[1] John Burnside [illustrations by Tim Robertson] (2021: 118) Aurochs and Auks: Essays on Mortality and Extinction Cornwall, Little Toller Books.

[2] Ibid: 74

[3] Ibid respectively 116, 117, 122,

[4] Ibid respectively 59 (Rousseau), 62 (Clare) and 55.

[5] Ibid: 113

[6] Ibid: 145

[7] Ibid; 7

[8] Ibid: 17

[9] Ibid: 101

[10] Ibid: 116f.

[11] Ibid: 7f.

2 thoughts on ““… every lapse from the imaginative into the ‘idées reçues’ of orthodoxy is disappointing”. This blog reflects on Burnside’s (2021) ‘Aurochs and Auks: Essays on Mortality and Extinction’ Cornwall, Little Toller Books.”