“… It’s a slow burn. Some people like things coming at them at a faster pace. That might be hard, but I felt it was probably necessary to get the full impact, the changes, and the way that the space rolls”.[1] Space, time and the passing away of the masculine super-hero in Jane Campion’s 2021 Netflix adaptation of Thomas Savage’s 1967 novel, The Power of the Dog.

Novels, and indeed films are so much more than the genre categories under which they can be sold and the ideologies they describe are not always as free-floating and independent of situated histories as we like to think. Take the idea of the ‘cowboy’: the hero of the ‘Western’. There comes a time when not only films and novels have to wear that category with circumspection, and perhaps irony, but so do people enacting that ideology in the wake of its historical submergence. There is a cruelty in the examination of people, whose role has been swept away by historical events and trends, as Shakespeare realised in dramatising Othello, a play about a man whose ‘occupation’s gone’. Savage wrote his novel in awareness that things in the American West were not just changing but in some ways had already changed irrevocably and were not to return. In these worlds, some ideas about, for instance how a ‘real man’ conducts himself, ought no longer to be holding sway, although it is of interest certainly trying to understand why it might be that for some people they did and who continued to enact the social roles they implied. This, in particular seems to have motivated the choice of this story by Jane Campion – it deals with anachronisms of the most potent kind, those, in particular determining gender roles and articulating our knowledge of the variations in biological sex. In an interview with Anne Thompson this year and after the film’s preview, she described it thus:

“It’s a ranch story,” … . “Nobody’s got a gun. It’s just on the end of that mythology when the cowhands are working there because they love cowboys of old and they are getting their clothes from the mail orders and dressing as cowboys as a kind of quoting of cowboys”.[2]

So much for the young men working the ranch owned by the splendidly rich Burbank family, whose wealth is not that of born ‘ranchers’ but of entitled and monied entrepreneurs, the people known as the ‘Old Lady’ and the ‘Old Gent’, who have decided to retire elegantly to a Western ranch, with their two young boys From the Easter sea-board. And the sense of a history that one wants to recapture (that of the pioneering West) has more to do with sentiment and nostalgia about the origins of an innocent and virgin state that never existed than with the USA as we find it today. Savage makes this clear in counterpointing his story of White Americans with the Native Americans who have already been swept off the face of the Mid West. Their story however, does not enter the film and this is a pity, especially that of Edward Nappo, a former tribal chief, and his son who attempt to travel back to the mountains from their reservation until they get stopped by Phil Burbank’s ranch borders and gates.[3] Thence, these native Americans get pulled into the whirlpool of the otherwise hidden conflict between Phil and his brother’s new wife, the widow, Rose, and that role being complete are forgotten by the novel.

The recall of a (false) history does however arise in the analogy the novel implies between men and their nostalgia about mental representations of their past boyhood. However it cannot be recaptured not only because time moves on inevitably but because the episodes mentally represented never actually existed other than in myth and ideology. Apart from his hands, Phil ‘never lost a certain boyish air’.[4] However, when Phil attempts to recapture a boyhood game by playing it with Rose’s son, Peter,– of testing a rabbit’s nerve as its safe space was depleted around it – the game goes wrong, the rabbit is damaged in the process and must be killed. Savage is interested however in the motives that drive Phil here. They emerge in reflection: ‘The rabbit thing hadn’t worked out. He’d failed to capture the nostalgia his heart required; …’.[5]

For though Phil may be dark and brooding in appearance, underneath that appearance he has barely grown up and has only a jaded and inaccurate knowledge of the contents of his heart’s desires. His recourse is to talk, yet again, about his boyhood hero, Bronco Henry, but Campion, even more than Savage really does allow us to see how much of a bore these ever repeated tales of undeveloped and non-developing masculine typology are. One almost groans when they are called forth yet again by those willing to form Phil’s entourage – the farm hands and, though probably in a way that has sinister undertone, Peter. This effect is a great achievement of Campion’s pacing of the film, so that it becomes about how we maintain the illusion of nothing changing, whilst everything really is changing – and massively.

Campion is popularly thought of as a filmmaker who tells stories at a slow pace and she acknowledges this in terms of this film in the interview, and particularly in the quotation from her interview I cite in my title,. She does so however with an explanation of at least part of the reason this may be the case, suggesting that it is an effect deliberately sought. For, if your theme is the process of change, through and in time, then the feelings viewers have about the duration and pace of the film are means of acting out this theme in no uncertain way, so that time and change are not just taken into account but felt as an aspect of the spaces traversed by the narrative. This is one way in which the almost nearly archaic symbols at the centre of the film are brought into focus as things undergoing the metamorphoses that must occur in the passage of time.

Hannah Innes Flint in the American game and entertainment Media Company, IMG’s online review pulls no punches in stating the case Campion predicts might occur to critics in her interview. For Flint there is no excuse for what seems to her the slow unrolling of predictable events in the second half of the film:

The slow pace that once enhanced the uneasy tone becomes a little tedious as we wait for the inevitable events to take place. Twenty minutes could certainly have been knocked off the runtime, but it’s still a striking world to be swept up in.[6]

Yet this is to assume that viewers are caught up in the suspense of narrative events rather than being urged to reflect thereon and feel the tedium of long-established events living out not their life but a kind of ghostly after-life which arise from events that must continue to their end but whose meaning has already been so established that our interest in it is already dead. For that is how Phil’s life seems. A faster pace would have gratified those who looked for an exciting tale of the American West in action but the danger of doing so would be to miss the point – that there is no significance to the action in this world or, at least not that significance which men seek in the imagery of machismo with its compulsory and compulsive aggression and aridity.

And the lack of significance infects not only action but also space, offering insights into its appearance, that however hard we look, few of us can see (like the landscape that is meant to look like the barking dog Bronco Henry once saw in its features, and the character of actors, especially men like Bronco Henry and his disciple, Phil, who feel they have a monopoly on action but do not know what to do with it. For the role of a man has to be more than look the part or even re-enacting the role but what is constituted by that more. That is the question? Military and lone fighting models are the usual recourse for that significance, as more accessible than the role of a hero to cleanse the World, or chart uncharted nature on the seas like Ahab or the Western deserts or plains of the USA like the Lone Ranger. It’s what people claimed to be the role of that superhero, Herakles, according to Euripides’ character Amphitryon:

He reclaimed the pathless land and raging sea,

and he alone held up the honour of the gods

when they wilted by the deeds of evil men.[7]

Yet what does Phil, or indeed Bronco Henry actually do to promote the value of their machismo. They set up posts in the ground, they ride around looking rather magnificent, at the best they play games with horses and steers and they braid leather. In doing so they look extremely good, though it is a beauty often shaded in chiaroscuro (these kind of shots often define Campion’s brooding shots of Phil – silhouetted against the light, especially in those shots where he look at Peter, who is facing the light and facing the future. For Peter is a possible future for masculinity in the diversity of the modern United States, as indeed is, more generally, in fact the quiet and reserved George, who develops an undemonstrative but decisive masculinity that is able to negotiate with the world of nature rather than confront it.

I love the way Savage calls that tremendous power George gains in book and film (so brilliantly played Jesse Plemons) by ‘a queer authority without even knowing it’ since he makes men look in on themselves and find their truer inner weakness and guilt.[8] Of course ‘queer’ means only strange but it is interesting that such men can accommodate and welcome women, nature and the supposedly feminine in appearance such as the bearing of flowers or the wearing of a gift from your mother that includes a ‘blue silk dressing gown’ and ‘queer slippers’ (my italics). The same passage queries precisely how ‘one man’ gets ‘the power to make the rest see in themselves what he see in them? Where does he get the authority?’[9] The point is that Phil thinks it comes from taking the lead, charting the unknown but essentially looking backward in history for his models – in his case to Bronco Henry. Does Campion choose to show that by showing Cumberbatch as Phil so often looking back on us or seen only from the back away from the light facing him? Phil, unlike George, never looks forward to the future for anything. All value lies behind him.

Peter is associated with blossoming flowers in the film as is his mother, conveniently called Rose, But his inner authority, which he keeps within is from the learning of his less father, Johnny, who dies as he lives refusing to allow that being a man and having authority should not depend on the control of inner sensitivity in negotiation with the ability to heal through knowledge gained from learning. Campion omits the story of Johnny who we know to be let go from a hospital because of his supposed ‘uncontrolled sensitivity’ and lack of ‘detachment’ which they believe to be no use for a doctor.[10] Nevertheless, he is the only doctor ever remembered by patients precisely because of his kindness, as Mrs Lewis, George and Phil’s cook shows us, in reflecting on her late husband’s medical care.

In the novel (but not the film) there is a confrontation between Johnny, Peter’s father, and Phil which starts precisely as a discussion of the value of the beauty of blossoming flowers, educated knowledge of medical anatomy AND the Greek language. This knowledge is available in fact to both men had (Phil was Harvard Phi Beta Kappa educated we later learn). Phil represses such sensitivity under the kind of violence which lets him despise ‘sissies’ (as he sees Peter at this time) and the cultivated strength of muscle which allows him fling ‘Johnny like a wet rag so that he smacked the wall opposite and fell in a heap’, an act that leads to Johnny’s suicide. Peter, but not Rose observes this violence (in the novel) and this becomes the reason for his coldly planned vengeance against Phil.

Yet none of this part of the story is in the film, which starts after Johnny’s suicide. Campion chooses to motivate Peter’s story as a fight-back against Phil but in order primarily to protect his mother. He is protecting his mother in the novel too but Campion loses that nuanced sinister aspect of Peter’s revenge by missing out the fact that Peter, like his father when he lunges at Phil for ‘calling my son a sissy’, is defending partly his right to be proudly that sissy, ‘Miss Nancy’ (or in the film ‘Faggot’) and quite openly, even before ‘jeering cowhands’.

In fact the image of Peter facing down masculine ridicule was central to Campion’s motivation for the film as she said in the interview already cited: ‘But she couldn’t shake images from the story, like a slim young man in a giant cowboy hat striding past a row of jeering cowhands calling him “faggot”’.[11] Her memory is somewhat faulty. The behaviour she turns into name-calling is in the novel men giving Peter’s ‘slightest feminine twitch of hips’, a ‘sharp’ whistle: ‘the whistle men give a girl’.[12] Film-makers presumably originate images from memory overlaid already by their own story-telling authority. For this is how that scene is played in the film.

In the case of BOTH novel and film this scene marks a turning point in Phil’s apprehension of Peter. In the novel we are told that Phil ‘could hardly stand’ that ‘feminine twitch’ of Peter’s hips. Here the novelist uses the third-person narrative voice to both describe Phil’s heteronormativity but suggest that it may be a reaction to some other feeling inspired by Peter that does not get spoken and is entirely interior to him. This gets him plotting – ostensibly as another way of getting at Rose, Peter’s mother, but his thought runs deeper for anyone who reads under the point of view of Phil to a deeper psychology: ‘Why, the kid would jump at the chance for friendship, a friendship with a man’.[13] This is a kind of projection into Peter of Phil’s feelings from the past, we have eventually to believe though it is NEVER spoken directly of Phil’s desire when he was a ‘kid’ for Bronco Henry who taught him how to ride and to be ‘a man’. So much is desire a possibility (Phil’s desire for Pete that is) that it sexualises his interior consciousness into acting like a phallus: ‘He felt suddenly possessed, bewitched, and his whole mind swelled with the idea’. Again in the novel, Peter (and any reader sensitised to unspoken inter-male interactions of unexpressed desire, can see this in Phil.

I find the moment when Peter says, “You want me, Mr Burbank?” It is a tantalising moment where text becomes stuffed with the sexual potential it can’t name. I think Peter is playing with Phil and he repeats ‘You want me?’[14] For Peter sees Phil’s desire for him quite clearly he is attuned to it as it were, just as he is the only one who sees a dog in the shape of the surrounding mountains as Phil and Bronco Henry did. In the film this is clear to – at least to me – that Peter knows the ambiguity of being wanted by another, and a supposedly ‘superior’, man.

The points I make above raised so many questions for me about how comparatively a film and a novel deal with desire that is unspoken but which it is yet the something we need to know if we are to understand the plot of any artwork that also ‘tells a story’, especially one concerning love or sexual attraction, in Forster’s resigned phrase. There is a decided absence of any exploration of Phil’s relationship to Bronco Henry apart from his constant admiring references to his skills as a man, including braiding cut rawhide. At only one part is Phil’s desire for Bronco told to us there, and then in a manner that is more than reserved in its manner, barely speaking its name, and easily mistaken for merely hero-worship with no lower register of reference. It is when Phil has ben led into a belief that Peter would offer a friendship to him (like that he offered Bronco Henry as a boy himself) that is sexually based even if that latter basis is totally unacknowledged between man and youth.

What reason for the boy to have rawhide but wanting to braid like him! To emulate him! … The boy wanted to become him, to merge with him as Phil had only once wanted to become one with someone. And that one was gone, trampled to death while Phil, twenty years old, watched from the top rail of the bronc corral.[15]

These sentences could not reserve their meaning more without becoming impossible to understand in a direst way. And this is the nature of narrative. It can be told from the point of view of a character like Phil and convey more than it does anything else Phil’s refusal to know and acknowledge his desire – but a good reader will of course see it. Another way of reserving sexual desire is to encapsulate it in sensations that are themselves symptoms of sexual arousal – but never so obviously that they cannot be denied. This example again takes the rope which Phil is braiding for Peter as a symbol of their otherwise unspoken connection, at least a connection from Phil’s side: ‘The rope, the bond between them, Phil kept coiled like a snake in a sack as he worked at the unfinished end, feeding it, as it grew, into the sack’.[16] This snake that is fed and felt to grow in one’s sack has the ability to signal sexual desire, even without the traditional phallic associations of the snake. Language could not be operating with more ambiguity here. In the book this has the effect of allowing us to see that Phil knows as little about the meaning of his sexual attraction to men as other men that his machismo demeanour conceals. And this is indeed how I see Phil, as fatally unknowing – his desires recognised for what they are more by Peter than by him. For this reason Peter can use the power of Phil’s sexual attraction to him without that ever being acknowledged by Phil or anyone else or contradicting himself in his belief that he had ‘the most rigid of morals’.[17].

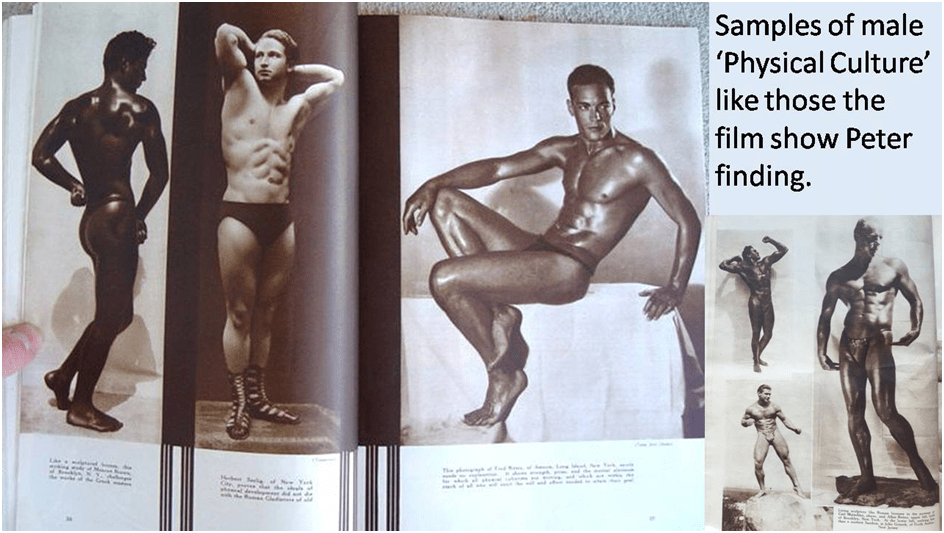

The complexity of illustrations of desire like those I cite from the novel above (that stay unacknowledged almost by anyone who sees them) are not easily available to visual art like that of moving film. The film add properties and business that give Phil away as a repressed queer man but that, unlike the book, imply that Phil must have been aware of his sexual nature too. The most obvious instance is that prefacing the scene before Peter finds Phil naked at his secret water-hole (a scene not in the books) when peter finds Phil’s hidden stash of Physical Culture magazines. These magazines were the sole source of pictures of male nudity for many queer men in the period covered by the film and before, and although not exclusively featuring male bodies, they were in there for the finding, and emphasised an almost perfect physical appearance in skimpily clad models.

That Phil possessed such magazines and hid them implies a consciousness of his own attraction to men which is not necessarily intuited in the novel. Moreover male desire is shown by visual images of film properties – objects that for par of the mise en scene and indicate sexual desire much more obviously. A key example is the import to the film of a shrine to Bronco Henry comprising the saddle of this superhero. We need to understand the anatomy of Western saddles to see how this is planned in the film and the actor directed,

When Phil handles Bronco Henry’s saddle he is seen to stroke the ‘swell’ of the saddle and finger its ‘horn’ (all terms in saddlery note). Nothing however could be a more obvious give-away of the sexual nature of Phil’s past attraction to Bronco Henry, except that there are even more obvious clues (too brash perhaps to be just clues). One is where Peter forces Phil to recognise that Henry kept him warm in one of their ventures by lying with him under the same bed-roll. Peter adds a massive hint of his awareness of what this could mean by hinting that they possibly lay there naked. Phil does not react in the film despite the lengths the story goes to show Phil hates being observed by other men ‘naked’, even by his brother when both share the same bed.

If that were not enough, in the scene where Peter inadvertently discovers Phil naked, Phil wears Bronco Henry’s saddle-cloth (conveniently monogrammed in red, ‘BH’, for the purposes of the film) around his head before then stuffing it down his pants in preparation for what is clearly marked as possible masturbation. Films, of course, are very different from novels but in these ways ‘desire’ cannot be understood in the film as a being the complex phenomenon it is as it can in the novel. The hints are too gross and not at all nuanced. And perhaps this has to do with Campion’s desire to make the analysis of masculinity more applicable to the twenty-first century. She told Anne Thompson that she had the model of masculinity posed by Donald Trump in mind in part:

Even Donald Trump has trouble keeping up his powerful male facade, she said: “Like, when things didn’t go well for him, he melted. He couldn’t ever even say the words ‘I lost.’ He created this massive fiction. Even to say the word ‘failure’ is just not an option for someone like him, for these kind of men”.[18]

And, as I have suggested before Campion’s conception of the characters makes much more obvious points about gender. The sinister side of Peter’s plot, in effect to murder Phil without it being noticed, is attributed to his defence of his mother. And this film makes Rose much more seminal as a lone woman, in part by never showing her first husband and his relationship to Peter. Campion needed to create a much more obvious bow to feminism by showing, for instance how family constrains Rose to the loss of her self-worth. This shot alone of the awful dinner party held for the governor and his wife by husband George – in the film but not book attended by George’s parents – tells a story of how one woman is alienated from everyone by her role and in a way that will explain her later alcoholism.

The problem is too is that it is likely that the role of Benedict Cumberbatch as Phil, and its brilliant nuance (despite the heavy hints from properties about his sexuality) will be missed too as it is in this comment by Hanna Ines Flint:

Cumberbatch embodies a particularly vile sort of fragile masculinity. He’s a disdainful man who gave up urban sensibilities for rural roughness but takes pleasure in beating down those he perceives as weak because he himself is hiding his own secret weakness. There’s a real haughtiness to this character and a visceral misogyny can be sensed every time he covertly and overtly targets Rose for ridicule.[19]

But I love this film. Its slowness is part of its threat. That time either leaves us all behind or, worse still, we will prey to its dog-like jaws and insistent and foolproof power; because in confronting Time’s passage we are all fools).

All the best,

Steve

[1] Jane Campion talking about how her upcoming film (this is about a preview) might disrupt a contemporary audience’s expectation of the best pace for film narrative, cited in Anne Thompson (2021) ‘Interview: Jane Campion Talks About ‘The Power of the Dog’ and the Myth of the Sensitive Cowboy’ in Indie Wire (online) (September 6th 2021). Available at: Jane Campion Interview: The Power of the Dog | IndieWire

[2] Ibid.

[3] Savage (1967: 164ff, Chapter 10 and following others).

[4] Ibid: 241

[5] Ibid: 247

[6] Hanna Ines Flint (2021) ‘The Power of the Dog Review’ in IGN (online) (21 October 2021, updated 8 November 2021, 6.46 pm) Available at: The Power of the Dog Review – IGN

[7]Euripides (trans. William Arrowsmith) [2012: 48, ll. 851ff.] ‘Heracles’ in David Grene & Richard Lattimore (Eds.) The Complete Greek Tragedies: Euripides III Chicago & London, The University of Chicago Press.

[8] Savage op.cit.: 121

[9] Ibid: 129

[10] Ibid: 22

[11] Thompson interview, op.cit.

[12] Savage op.cit.: 215

[13] Ibid: 216

[14] Ibid: 217

[15] Ibid: 250

[16] Ibid: 225

[17] Ibid: 210

[18] Thompson, op.cit.

[19] Flint op.cit.

2 thoughts on ““… It’s a slow burn. Some people like things coming at them at a faster pace. That might be hard, but I felt it was probably necessary to get the full impact, the changes, and the way that the space rolls”. Space, time and the passing away of the masculine super-hero in Jane Campion’s 2021 Netflix adaptation of Thomas Savage’s 1967 novel, The Power of the Dog.”