‘…/ We all profit from him, from / his so-called soteriological instincts.’ ‘Too bad if it leaves him / outsize and outside / the civilization he’s saving’.[1] This blog reflects on the social psychology of the hero as saviour in Anne Carson’s new version of Euripides’ Herakles (2021) ‘H OF H PLAYBOOK’ London, Jonathan Cape, Penguin Random House.

This is a republished version based on additions and revisions after reading Anne Carson’s first translation of Herakles in Anne Carson (2006) Grief Lessons: Four Plays: Euripides New York, New York Review of Books Publishers. 11 – 85.

Why anyone would desire to ‘save’ the ‘civilized’ world in which they were born and grew up is an interesting question. First, it requires a belief strong enough to commit you to action THAT civilisation is under immediate threat from forces either inside or outside of it; second, that this civilisation is worthy of preservation and, third and finally, a strong belief in one’s ability and resources that match the tasks that this job requires. According to Emma Heath in The Chicago Review of Books, belief in heroes who have precisely this instinct to save the world is necessary to societies that wish to portray their own social and cultural world positively. Without such belief, it would be more difficult to rescue themselves and the group of others they identify with from feelings of existential emptiness and despair. Indeed so much is this case that we feel uncomfortable when heroes we have already identified or the concept of heroism itself are questioned. And Heath continues, Euripides in each of the ‘92 plays he wrote from 438 to 405 BCE’ caused such discomfort to his audience deliberately, and perhaps at the cost of being a totally acknowledged success, since only four of those plays won the coveted first prize at the Dionysia in Athens.[2]

Heath goes on to say that the questions posed by Euripides in his original plays, including Herakles, to his audience of Athenians were all about the nature of the hero. Hence a play basing itself on the iconic Greek hero – half-man and half-god, Herakles, armed with weapons and clothed in the skin of a lion – raised these questions more forcefully. The play appeared during the period of direct democracy in the polis of Athens, threatened, as Athenians saw it, by Sparta and the values of Sparta: those of an oligarchic, land-focused and military mindset. Sparta in its turn was a government suspicious of the more open society of Athens (but not a society that therefore denied itself slaves). The Athenian city-state’s wealth was based on trade and especially the naval supremacy that supported such trade. Dependence on such a watery world implied some flexibility and tolerance to crossing boundaries. Yet Euripides, says Heath, made Athens ask if it was really a social organization worth saving:

His plays were formally experimental and morally ambiguous; they asked sticky, inconclusive questions like: Should we really valorize heroes, like Herakles? What is a hero? Aren’t they just people who sneeze and lie like the rest of us? What has our country become? Is this really the pinnacle of civilization? How can the gods be just when horrible things happen to us?[3]

When Anne Carson first published a translation of this play, she was already very sceptical that Herakles is presented as a hero. Indeed she claims in her preface that Euripides was determined to go beyond the hero mythology and stereotypes to look rather at how a thing so divided as Herakles (a ‘two-part man’ she calls him in regard to Euripides’ play).

Euripides assembles every stereotype of a Desperate Domestic Situation ans a Timely Hero’s Return in order to place you at the hear of Herakles’ dilemma, which is also Euripides’: Herakles has reached the boundary of his interestingness. now he’s finished harrowing hell, will he settle back on the recliner and watch TV for the rest of the time? … A man who can’t die is no tragic hero. immortality, even probable immortality, disqualifies you from playing that role.

Anne Carson (2006: 14) ‘Preface to Herakles’ in Anne Carson (2006) Grief Lessons: Four Plays: Euripides New York, New York Review of Books Publishers. 13 – 17.

Euripides’ own words in the play however stress not only the individual hero but the relationship of Herakles as that ‘hero’ to his community. They generalize that community such that it stands for many different understandings or levels of community: not only for the aristocratic and sometimes royal house of his human father, Amphitryon, or even for the city-state of Thebes but the whole of Greece, ‘Hellas’. William Arrowsmith translates the word Euripides uses to denominate that relationship of hero to nation (ἃ τὀν εὐεργέταν) as ‘saviour’ which rather overdoes Herakles’ spiritual role. The term ‘saviour’ goes too far in identifying Herakles as a type of Christ as he was in early Christian iconography.

μέλεος Έλλάς, ἃ τὀν εὐεργέταν

ἀποβαλεἲς ὀλεîς μανιάσιν λύσσαις

χορευθέν’ ἐναύλοις. [4]

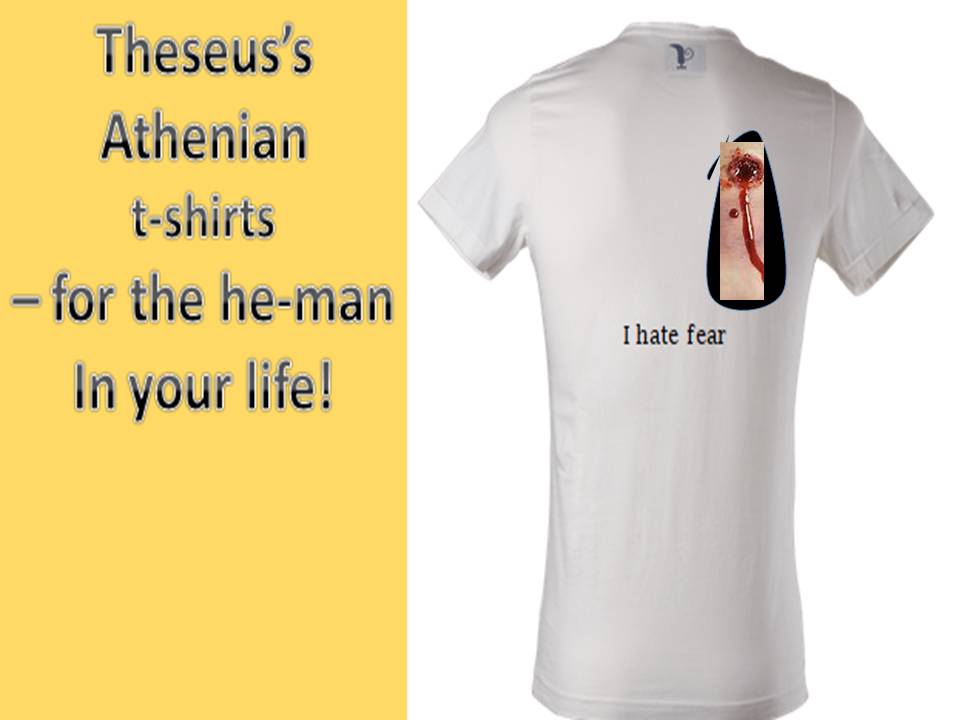

The term εὐεργέταν is translated as ‘benefactor’ in the Loeb edition. This idea is important for Carson who calls her Herakles ‘H of H’, or Herakles of Hellas, as I understand that name, at least at its simplest level of connotation. She also chooses the word ‘benefactor’ rather than ‘saviour’ to describe what being a hero means to ‘mankind’, though in the ironic voice of a rather jaded Theseus, as he teaches Herakles that ‘being a hero’ is a particular kind of ‘commodity fetish’ for sale to the general public. For his purposes that public is a cosmopolitan Athenian public – with anachronistic access to Sotheby’s, the very pinnacle of ‘commodity fetishism’ in action.

… . I’m thinking of a T shirt

Lionskin background. You wear it, you shoot yourself,

I sell it, say Sotheby’s, bullet hole and all.

…

No joke. We put I HATE FEAR on the back. Small font.

Helvertica Bold.

In H of H Theseus plays cruel public games with Herakles, taunting him because he falls to crying in public, Theseus urging him to look more like the ‘all-enduring H of H … Hero and benefactor of mankind’. Though H of H replies that ‘Mankind gave not a fart for me’, Theseus in turn teaches him that ‘heroes’ are in fact manufactured to serve any needs but their own, even the physicists who obeyed orders to minimise the threat posed by Chernobyl. Being a ‘hero’ and considered a benefactor of one’s society is more a matter of luck than an assessment of one’s true value, where any object to be deemed to have any value other than its market price. This is why the Chorus are very knowing in their word choice when they value his possibly innate ‘soteriological instincts’ (we are back to the analogy of the son of Zeus with the son of Yahweh) as something we all ‘profit’ by.

There is no doubt that H of H, though a genuinely remorseful softie in Carson’s new version, is also the principle of ‘organized violence’ (again in Theseus’ words) whereby societies mercantile or military justify their values whilst requiring the bearer of that function to at least look good. It’s no accident that heroes must be ‘a soul too big for the space of life’ those in charge of things ‘give you to live in’. Heroes are fictional inventions that please the public in the words of the Lykos too; the ‘totalitarian cracker’ who now rules Thebes and wants H of H’s sons dead. Heroes are fictions he says ‘in the standard sitcom’,

where / the awful hero strides in bare-

Chested and saves the day’.

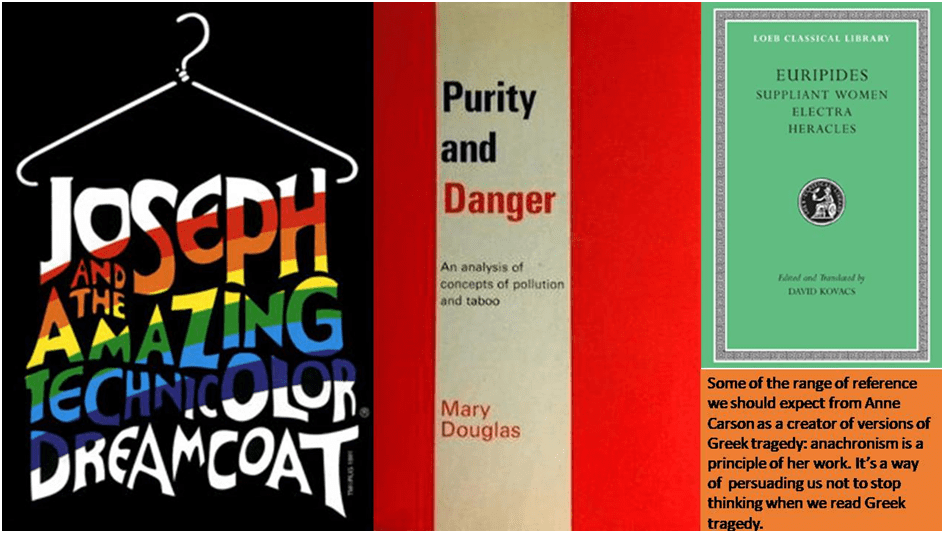

The Chorus, a little later in the same scene, make the same point. The hero is a function, using the views of Mary Douglas’ book Purity and Danger, of the need of the powers that be to make a society that in fact only profits their interests by making society look cleaner and more pure than it is. Hence ‘purifying civic space’ hardly makes H of H a ‘hero’; rather he is an advertising icon for the status quo. The Chorus says later in the same scene that, in order to look the role he plays, he must be left: ‘outsize and outside / the civilisation he’s saving’. Thus goes it with benefactors and ‘saviours’ both. They are dispensable like his children, little more than ‘tragicomic dreamcoats’, presumably referencing the musical about the Biblical Joseph.

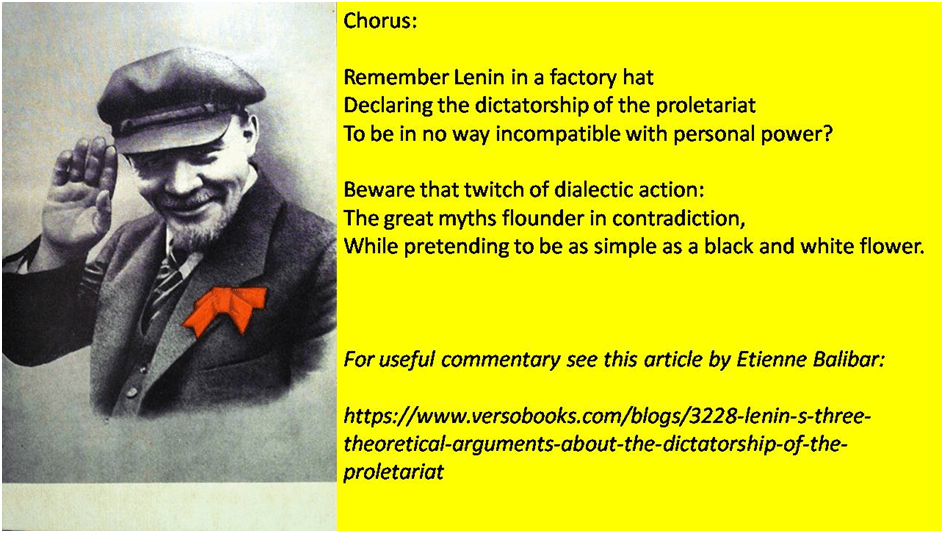

These are the very least of the anachronisms of reference in this play, for H of H is all heroes and all the circumstances which birth the contradictions of their action, whilst understanding themselves or being understood as heroes attempting to, in some way, ‘cleanse’ a dirty world. Most important in this list we’ll eventually find Geryon, the hero of Carson’s early versions of Stesichorus’ classical verse narrative in her early books Red: An Autobiography and Red Doc>. However, the most notable hero from the offset is Lenin, hero of the Russian Revolution and a man as compact of contradictory myths as Heracles. On the Chorus’ first entry in H of H they sing a song about precisely that:

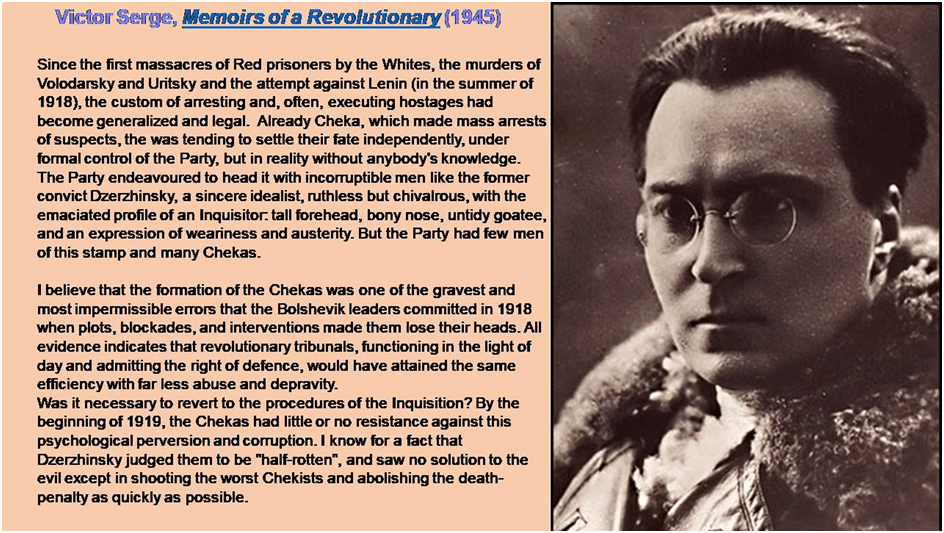

H of H too describes the contradictions in his own experience in one of the ‘voiceovers’ that engage with his own subjective take on his past, and especially the process of the Labours as ‘a knot I had to untie’. The passions and violence required to engage in a war to ‘cleanse the world’ are already in contradiction with the aims of the civilisation you want to achieve. Heracles finds and reads, he tells us, Victor Serge’s Memoirs of a Revolutionary, through which he illustrates the conflict between revolutionary idealism (citing Lenin’s determination to end ‘capital punishment’) and the violent murder which others decided must be used defend revolutionary change from counterrevolution. He cites a piece of this text you might also read at the link here.

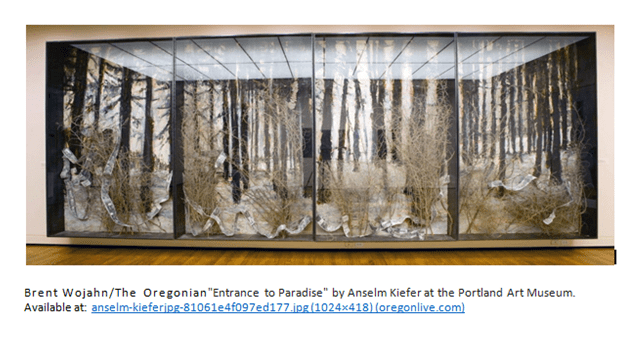

“I think there is no such thing as an innocent landscape,”

said Anselm Kiefer, painter of forests grown tall

on bones.

‘We all profit from him, from / his so-called soteriological instincts’, sings the Chorus twice in this play about how a man who claims to be our benefactor or saviour can also often just be used as a means for those defending the ‘status quo’ to ‘profit’ them, as they profit from other commodities. We can blink at the violence in, for instance, Anselm Kiefer’s forest landscapes, sometimes an image, as Simon Schama shows, of how the German nation, in accepting Hitler as a saviour, forgot the violence feeding the forestation he promoted – a belief the Chorus anachronistically cite:

This concern is somewhat different from the Euripides’ Herakles, in which a chorus of old Theban men who back up the aged mother and human foster-father of Heracles see the hero’s wished for return from his labours and the underworld as a return of youth to life in the process of dying, of spring after winter. Carson in 2006 (ibid: 17), points to this level of renewal and age-reversal metaphors in a footnote to her Preface to the her first published translation of the play. There she points out that ‘youth and age are thematically present in every choral ode and also in certain striking mimetic gestures of the play: (there follows here an exhaustive list of examples in evidence)’. The return of Herakles however does not renew Thebes (Herakles’ primary community) but Athens. Thebes here yet again falls foul of the comparison of the city-states typical of Attic tragedy – the one as the future, the other of a decayed social and political past ruled by an oligarchy, the other of contemporary (from Euripides historical perspective) democracy. For Carson, Theseus merely uses H of H to rebrand Athens and profit from that rebrand.

And as for H of H himself, he is locked in a forest of myths. Those which his human father, if not his divine one, wish him to identify with are those modern bourgeois ones of the ‘family man’. Amphitryon invites him to: ‘Go into the house, get used to / how normalcy looks’. Herakles’ wife, Megara, insists that this normalcy was that of a conventional heterosexual masculinity, although she appears to protest too much and too repetitively: ‘I think we are in his zone now, we’re okay. We’re okay. H of H was a stud from the very beginning, yes he was. We had a real first night I can tell you’! (my italics).

Yet the whole play insists that H of H often escapes the normalcy expected of him such that his Labours are presented as so much of the hip hitchhiker escaping the expectations of normativity, including heteronormativity, and modelling himself on a god; living a ‘completely socialist existence’. The ‘normalcy he returns to is that of a capitalist system with values that look immediately ‘debased’ to him’: ‘You think psychopathy has nothing to do with the capitalist system? You’re wrong. Capitalism farts cruelty like gas from a lawnmower’ When the double-character, Iris-Madness identifies herself as ‘split-brain’, it is as a prelude to inviting Heracles to be ‘buried alive in’ his ‘own mind’: ‘It plays you it plays all the enemies you’ve ever had it is a living person but it is also hell’. This is not merely post-traumatic illness; it is a total fragmentation of self. But it is not less than we see in Herakles elsewhere outside the plans of normative life. For the puzzle of H of H starts with the duality of his fathering, expressed by his human father, Amphitryon, thus:

Zeus claims to be the other (father): there begins H of H’s glory

and a fair amount of worry

ontologically.

That half-feminine rhyme on ‘worry’ and ‘ontologically’ is telling. It draws us right into the problem of defining H of H’s ‘being’: ‘Olympian overall’ standing against ‘mortal shortfall’. The rhyme makes the point again, as the text makes clear: Dumb rhyme / for a complexity more sublime / than the self can ordinarily bear’. You cannot define H of H or say exactly ‘what’ he ‘is’ other than having ‘good looks’; his self diffuses before it ever gets a chance to cohere, even before he meets Iris/Madness. Spending his time routing ambivalent creatures – like the Centaurs – only to find that in a world without them, he is ‘lonely’, having nothing to mirror his own complexities and queerness. This leads him to note the difference between what he does and what is rumoured of him, but it is clear that these things are guided by an intrinsically sexual as well as ontological queerness, stuffed with denial that sounds like desire, as he mixes up the story of the Hesperides maidens and Atlas, quickly insisting it has ‘’no bearing on myself and Atlas, who did not attract me in the least’. All this is a prologue to a more clearly defined queer encounter with a socialist hero from whom he borrows books by Victor Serge, already mentioned and whose heart he breaks.

This story was told twice by Carson, so central was it to her view of human identity and sexuality. First in Autobiography of Red and second in Red Doc>, the latter of which was my introduction to this great poet and indeed Stesichorus, the poet whose works books were versions thereof. Yet only those who know these books will recognize how the colour red works – which it uses often to colour its pages, and at other times stain them in the graphic elements of the book. Sometimes recalling the colour of the Communist International at one level, passion at another and blood or other body fluids, even brown ones, which introduce the interiors of the body to the surface of the page in its most literal embodiment as ‘shit’. Red lives at the cognitive, emotional and embodied levels of this drama text. As a visible colour or a verbal motif, ‘red’ only connotes the early work of Carson if we know of it as one of many of the texts speaking of the Labours of Heracles or any part of them, for: ‘Important poets made songs of praise. Some had different versions, different lists, revisions, omissions.’

Nevertheless when we see the ‘tall, redwinged man’ in H of H we meet the Geryon of Stesichorus as adapted in Carson’s The Autobiography of Red who reddens all: ‘Grass was beginning to look red to me’. This Geryon has yet again been revised – now to become an old man who was ‘beautiful once’. This arcane self-referencing has interesting effects, such that I, at least, read the confessional text here to reference Carson’s voice behind H of H, except that the book she refers to is the youthful distraction of writing the book The Autobiography of Red itself: ‘You see I was quite stupid in those days. And the book distracted me – …’. When H of H describes engaging with Geryon it is as a rape that could pass as violence for its own sake: ‘I would jump him, neutralize his weapons, secure his arms (wings). Then explain my situation and hope he went he along’.

Readers who know the earlier book will recall the chapter from Autobiography of Red called ‘Sex Question’, in which Carson discourses about the meaning of sexual activity in the drama of the engagement between the two queer-bodied men, where the suppression of sex becomes a focus that not only stops them talking about it but also doing it other than as an unshared fantasy – like a mutual shared wound from self-harm that fails to understand its motivation. However, this is the resolution wherein they are ‘joined in astonishment as two cuts lie parallel in the same flesh’. It occurs because Geryon, at age 14, asks Herakles, then 16, to pick ‘their way carefully / toward the sex question’ – to the articulation of what might satisfy their bodily needs. Nevertheless:

… Hot unsorted parts of the question

were licking up from every crack in Geryon,

he beat at them as a nervous laugh escaped him. Herakles looked

Suddenly quiet.

Anne Carson (1999: 44) Autobiography of Red London, Jonathan Cape

That is beautiful, precise and so knowledgeable of how both queer sexual desire and normatively orientated sexual repression can be learned at the same time in an encounter between two young and inexperienced young men.

I believe that this reference places this text in the sequence of Carson’s work as another sublime representation that queered relationships underlie relationships of the most normative type but as a mirror inversion of them that people try hard NOT to see. Thus once H of H perceives his ‘Labours’ not as heroic but an escape from the normative human condition, he finds when he comes ‘home’ to that supposed normalcy that, ‘I look in the mirror and the mirror is uninhabited. (Carson’s italics)’ This is no longer a ‘home’ but yet another lonely unsatisfying place where the ‘kill the thing we love’: ‘a dull motherfucker most of the time’ where after fantasy of queer fulfilment is ‘routed’, the existential entity is essentially isolated: ‘I was lonely’.

We can finish then with best sentence in Emma Heath’s review to which I have already referred: ‘In one beautifully bound book, she has stitched together the Anne Carson starter pack in Euripidean gift wrapping’. We need perhaps to have Heath’s knowledge of Euripides to understand this but this a good summary of that knowledge, one with which I fully agree (from my admittedly more junior acquaintance with the texts):

It’s a pretty bleak outlook. And yet, from the crack of tragedy comes the shooting bud of absurdity. Sandwiches, farts, and overalls gallop through the pages. As illustrator and translator, Carson creates a conversation between the visual and the written, that — like with modernity and antiquity — forces the reader to leap back and forth, while the meaning weaves in between.

That bleak and dark vision will alienate many readers I know, but poetry was never meant to be easy or make the world so, unless it is bad poetry and neither Euripides nor Carson are bad poets, however ‘braced in my hero’, …’as a poet once said’, she gets H of H to say quite enigmatically.

All the best,

Steve

[1] Quotations are from Anne Carson (2021) H of H Playbook have no footnote. There are no page numbers in the first edition text. I t may be useful to know that the first one on my title in fact occurs well after the first one. There is a cyclical return in the play to the theme of ‘saving’ the world and the actors and actions that make that claim about themselves and what such actions might entail in any civilization.

[2] Emma Heath (2021) “Theatre Reimagined in “H of H Playbook” in the Chicago Review of Books (online) [October 27, 2021] available at: theatre reimagined in “h of h playbook” – chicago review of books (chireviewofbooks.com)

[3] Ibid. Heath’s italics.

[4]David Kovacs (Ed.) (1998: 392) Euripides Suppliant Women; Electra; Heracles Cambridge, Mass & London, Harvard University Press (Loeb Classical Library) translated as: ‘O Hellas, mourn! You have lost / your saviour!’ in William Arrowsmith (2012: 49) ‘Heracles’ in David Grene & Richard Lattimore (Eds.) The Complete Greek Tragedies: Euripides III Chicago & London, The University of Chicago Press. When Carson translated the play for the 2006 collection of translations she stays with a more modest ‘O Greece, you are losing your one true hero – ‘ (Anne Carson 2006 op.cit.: 55. ll.844).

One thought on “‘…/ We all profit from him, from / his so-called soteriological instincts.’ ‘Too bad if it leaves him / outsize and outside / the civilization he’s saving’. This blog reflects on the social psychology of the hero as saviour in Anne Carson’s new version of Euripides’ Herakles (2021) ‘H OF H PLAYBOOK’”