‘“April,” he said, the name giving Phoebe a start, until she realised it was the month and not her missing friend he was speaking of, “An undependable time of year – you wouldn’t know what it was going to do,” and she understood her mistake.’.[1] Reflecting on John Banville’s (2021) ‘April in Spain’London, Faber.

Of his last novel, Snow, I said in my blog (use link) that it was ‘a novel like no other by John Banville’ but after the publication of April in Spain we can see that it clearly indicated an intent in the redirection of his writing in his own name. I will argue below that it seems that this novel is the Spring novel, following Winter’s Snow, in a possible quartet of novels based on the seasons, but of this later. But this new novel confirms another thing; the intention that Banville is herein swallowing whole the work of Benjamin Black, his detective-writing nom de plume of the past, and building it into the memories of Quirke in this novel, including his relationship to his daughter, in this book much of the past life we have already been told about across the Benjamin Black novels.[2] And even the characters in this novel are characters that have lived in Black’s novels and experienced its settings – such as the house of sexual abuse by Catholic priests at Carricklea, which have scarred not only Quirke but Terry Tice, the murderous gunman of this novel.[3] The plot centres on a character from a Black novel, whom we, like Quirke and Phoebe Griffin, his biological daughter, thought to have died. This is the chief of the many resurrections that this novel involves. One of the tropes of the novel (one we shall see as h rich, Gothic and, at the same time, joky) is that of ‘April’s return to life’.[4] This theme gets its full Gothic sense – of the corpse resurrected – in Phoebe Griffin’s (Quirke’s biological daughter) childhood dreams: ‘Sprouting at an angle out of the grave, …, was an arm’.[5] April is, after all, a time for sprouting, as we shall see later. One of the purposes of these resurrected narratives is to create organic links between the Quirke in this novel and he from Benjamin Black’s series of Quirke stories.

But this novel also cunningly displaces Quirke and explains why it needed to follow on from Snow (wherein Quirke is mainly only referred to but not seen). It reintroduces Snow’s Detective Inspector St. John Strafford and builds the likelihood of a love relationship between him and Phoebe Griffin, to deepen the links between Quirke and he. Are we looking towards a Summer wedding? And a major shift of the main character in Banville’s new detective oeuvre to this younger Protestant is also that he may be being primed to take over from the aging Hackett, the chief policeman of the Black novels? But this is all speculation, of course.

What have we in this novel? Given the fact that younger peers of Banville as a novelist – novelists like Colm Tóibín and Sebastian Barry, perhaps for different reasons, have worked hard to make some of the shadier oppressions of Ireland and Europe’s past more rich and less riddled with predominant stereotypes, I have to admit that it is difficult to say the same of Banville. The past he brings back to life is scarred by an unredeemed set of stereotypical queer and Jewish characters (though surely Quirke’s wife the Jewish Austrian Evelyn, whose family survives the Holocaust, is an exception). It feels harmful to have the main go-between between corrupt government and murderous gangster underworld, that includes terry Tice, is constantly referred to as ‘Jew boy’.[6] Phoebe’s discarded boyfriend, of couse, Paul Viertel, is also a Jew and this fact is made to count.[7] Some of this feels anti-Semitic, whatever Banville’s intention was.

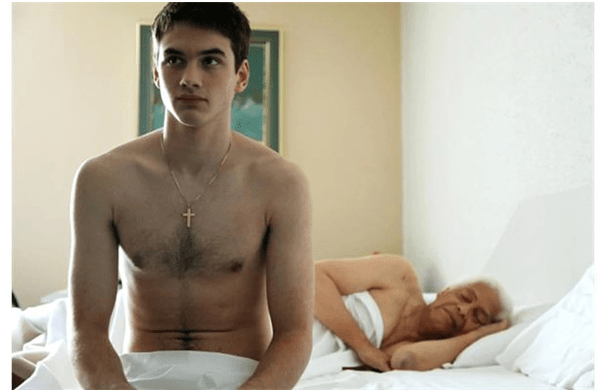

The word ‘queer’ in this novel is liberally used – once only just to mean ‘ill’ – but always with negative connotation. Even when it is used to mean ‘ill’, it is used of Terry Tice in the context of his attractiveness to old queer men, and in this case Percy Antrobus, who is plying him with the very drink that left ‘him feeling queer for days’. [8] His attractiveness to ‘old buggers’ makes Terry think ‘what it is about him’ that does that. But he accepts being kept by Percy nevertheless and a rather lack-lustre sexual relationship, which is made anything but attractive. Percy’s mouth for instance is described as an anus, for obvious reasons: ‘pursed into a crimped little circle that looked less like a mouth than a you-know-what’ and a ‘little pink puckered hole’.[9] The corrupt government administrator, Ned Gallagher, too, who commissions April’s murder by Tice, if indirectly through the ‘Jew boy’, is subject to corrupt ministers because ‘the Guards had caught him in the gents’ convenience …, on his knees in front of a young lad with his trousers around his ankles’.[10]

However, even if we have to make allowances for a curmudgeonly insistence on reproducing attitudes as he thought they were at the time in Black’s and Banville’s novels, this novel retains the signs of a still sprightly and very literary writer, whose jokes are sometimes as deep as his prose is lucid. Even the title, which appears as a phrase in the novel too, is a kind of clever literary joke referencing the return of the repressed (Freud himself is discussed many times in the novel) and the modernist literati who also appear in Snow via, in that case, James Joyce. T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land is referenced by Evelyn in a discussion about April Latimer, then thought to be called Angela Lawless, to identify the piece of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde quoted in that poem, in which Evelyn identifies Lawless as ‘Mein Irisch Kind’.[11] It is Angela’s Irishness, and a mistaken association to acting and thence to Quirk’s past relationship with actor Isabel Galloway (she is an inadequate actor in a very real sense) to acting and the theatre of stage plays rather than surgery,that eventually enables the mental links to be made that identify her as April Latimer.[12] We need to remember that The Waste Land is set in April and in a context of resurrection after the snow (Snow) of Winter:

I. The Burial of the Dead

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.[13]

And the opening of Eliot’s poem is itself a memory and disturbing metamorphosis through repressed sexual content of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales.

Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote,

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licóur

Of which vertú engendred is the flour;

Whan Zephirus eek with his swete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his halfe cours y-ronne,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open ye,

So priketh hem Natúre in hir corages,

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

…[14]

Of course there is ambiguity in the title: ‘April in Spain’; where April is at the same time a noun naming either a month or a young woman, or it is an adjective describing spending this duration in a holiday resort, as in the idiom, ‘they decided to April in France’. To ensure this ambiguity is understood, Banville reinforces it in Phoebe’s discussion with the weather-obsessed Hackett:

“April,” he said, the name giving Phoebe a start, until she realised it was the month and not her missing friend he was speaking of, “An undependable time of year – you wouldn’t know what it was going to do,” and she understood her mistake.[15]

Both poems I’ve already cited play on April’s undependability, at least in Dublin, but their deeper concern is with its association to fertility, sex and breeding and, of course, rebirth, but they have each a very different tone and purpose. Banville, i think exploits the Gothic qualities of Eliot’s verse with the lyric pathos of Chaucer – for April Latimer only seems as ‘cruel’ as the month Eliot so describes to men, who construct her as wild and dangerous, even her brother with whom she had, it is believed by men in the novel, an incestuous relationship. Yet both her and her brother was also raped by their father and it is this primal incestuous abuse that recalls Quirke’s own fear of abusive men (and priests). It is Quirke’s dark consciousness that makes her seem cruel I’d argue: she is given agency for having ‘laid a shadow on his mind, like the shadow that lingers after a nightmare, …’. But elsewhere on the same page, it seems clear that his perception of April Latimer is actually projected on April, as his wife Evelyn the Austrian Freudian psychiatrist could have told him; ‘when he pictured the young woman’s face. Something seemed to twang inside him, producing a dark tone that came out of the past’. [16] The past it comes from is his own deeply repressed past and it this that gets unburied. Men, and Phoebe, continually see April as ‘wild’ and in need of taming, as in these two instances:

… Spain would suit April. Surely that country would be lively enough even for her, with its bullfights and its flamenco dancers. People used to say of April that she was ‘wild’. Had she been tamed by now?[17]

April Latimer sat as he [Quirke] had seen her sit that first time, … But she was not the same person. It was as if animal, half-wild and long lost, had come creeping back in search of sustenance and shelter, furious at herself and the world for being thus demeaned.[18]

For, though April, the young woman, seems wild, she is so because men have continually degraded her sexually and as a person. She has never known how to feed or be fed, and that is why we see her at dinner eating nothing at all.[19] April’s ‘return to life’ is most inconvenient to her father who orders her death in response. So many people though ‘had desired her’.[20] And it for this reason she is equated with spring. Spring is as season Phoebe ‘had never understood the fuss people made about’ it: ‘… it was the season of ill-content, of unassuageable agitations’. Yet again we are told ‘the smell of spring rain always brought with it a sense of vague yearning’.[21] Chaucer’s ‘shoures soote’ (sweet showers) become Dublin’s ‘soft spring rain’.[22] The poets ‘tendre croppes’ (tender shoots) go specifically unnoticed by the father of lies (and April), child-rape and a Government Minister, William Latimer: ‘The trees in Merrion Square were dusted with spring’s first green shoots, not that he noticed’.[23]

Banville has, in this novel, now done Spring and I predict that his next novel will feature Phoebe and St. John leading the way to a new pairing as detectives in a summer setting. And why not? Banville is an immensely accomplished planner of novel sequences. I enjoyed this novel. And Phoebe has a good eye for an empathic take on even the worst of killers such as Terry Tice. This is a beautiful moment in which she is at her noticing best, seeing the victim even in Terry tice: ‘Someone really should tell him about those fawn trousers, they gave him the look of a prematurely aged and ravaged boy’.[24] And that is indeed what, at one level, he is.

All the best,

Steve

[1]Banville (2021: 189f.)

[2] For instance, Quirk’s past relationship with the actress Isabel Gallagher (ibid: 35, 166), the story of Phoebe being given up and reclaimed and her past relationships, (ibid: 181, 240), Evelyn’s Quirke’s story as a Holocaust survivor and migrant(ibid: 36, 217), and the story of the Latimer family and their links to corruption and incest (ibid: 144, 158).

[3] ibid:71, 173.

[4] Ibid: 145

[5] Ibid: 150

[6] Ibid: 248 – 251, 256.

[7] Ibid: 290

[8] Ibid: 178

[9] Ibid: 6, 9 respectively.

[10] Ibid: 208

[11] Ibid: 103

[12] Ibid: 34, 83.

[13] Available at: The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot | Poetry Foundation

[14] ‘The Prologue’ to The Canterbury Tales. Available at: The Canterbury Tales: General Prologue by… | Poetry Foundation

[15] Banville (2021: 189f.)

[16] Ibid: 99

[17] Ibid: 182

[18] Ibid: 340

[19] Ibid: c. 114.

[20] Ibid: 148.

[21] Ibid: 199f.

[22] Ibid: 153

[23] Ibid: 202

[24] Ibid: 232

5 thoughts on “‘“April,” he said, the name giving Phoebe a start, until she realised it was the month and not her missing friend he was speaking of, “An undependable time of year – you wouldn’t know what it was going to do,” and she understood her mistake.’.[1] Reflecting on John Banville’s (2021) ‘April in Spain’”