This is a blog on portraying the artist amongst ‘the unsung heroines and heroes of British art from 1880 to 1980’. The Laing Gallery and Liss Llewellyn discuss paintings from this period in terms, amongst others of (i) the spaces they use; (ii) the self-image they prefer to show and; (iii) the meanings they attribute to the process of creation. The blog uses both a visit to the Laing on 13th November 2021 and Sacha Llewellyn & Paul Liss ‘Portrait of An Artist’ (with a ‘Venue Statement’ by Julie Milne, Chief curator of Art), London, LISS LLEWELLYN.

It is always a delight to visit the Laing Gallery in Newcastle and it wonderful to visit without any preconception about the artists involved, especially because this exhibition focuses on relatively unknown (or at least ‘unsung’ as Liss Llewellyn describe them in their mission statement). In the ‘Venue Statement’ to the exhibition publication, Julie Milne gave us all a fact that I had not been aware of before, that the Laing bequest was not based on the donation of a pre-existing art collection, as was the Shipley bequest in Gateshead, but on a belief that a city needed an institution that would in Alexander Laing’s words be an ‘encouragement and development of British art’ and that supply of art to it would follow that need. Of course the history of its acquisitions since then was surely much more complex than that, but this start may explain in some part the richness of a vast collection of individual pieces that don’ t quite have a theme traceable to a unique perspective. I make a note about this as a Postscript to this review based on a quick survey of the pictures that did not ever go much deeper than recording likes and dislikes.

The eccentricity of the Liss Llewellyn vision, based on personal likes and a subjective view of what matters in art, is explained by Paul Liss as intensely personal in its subject-matter and process of interpretation: a place ‘where can revel in the self-gaze of an artist, or the frisson that suggests the artist was in love with his or her subject’.[2] Liss and Llewellyn divide the selection in their publication into rough categories and which are somewhat reproduced in the exhibition sections but not always in the exact same way. They name them ‘Working Space, The Artist’s Entourage, Artists by Artists, Self-Portraits and Allegories of Creation’.[3] There are several reasons why I have limited further these categories. First the Liss Llewellyn book already contained items from the Laing’s permanent collection, listed in the ‘Foreword’, but even these additions do not reflect the exhibition I saw for that uses the Laing permanent collection (and some from the Shipley collection) as a addition or sometimes a substitute for some of the items in the book. These additions are not necessarily the items Liss Llewellyn list. [4] Of course I also refer here to my personal selection from the whole collection, which I only categorised after the event. Hence the headings I deal with are different even if related to those already quoted. I dislike the term ‘entourage’ and I have discarded any attention to paintings of significant others, whether of other artists, lovers, or family members except in so far as they are important in other categories – such as venues which might also be labelled ‘homes’. In a way this is a pity since Liss Llewellyn argue that such sometimes include those in which we can detect ‘the frisson that suggests the artist was in love with his or her subject’.[5]

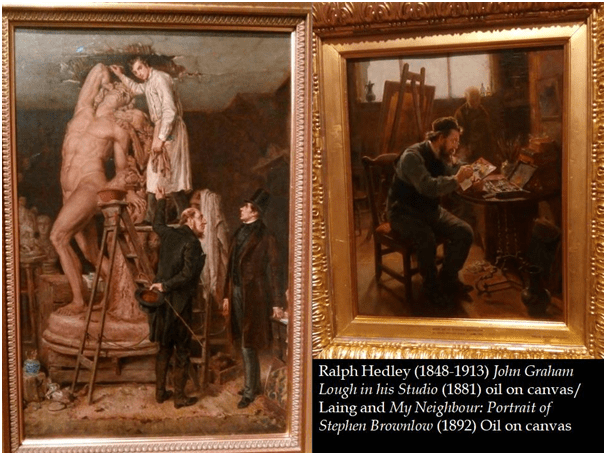

However this section is there in spirit. For instance, I have shown how we need to consider significant others in considering other categories used by Liss llewellyn, for instance, in considering Duncan Grant’s painting The Hammock or implicitly in Hedley’s picture of Stephen Brownlow. After all, the title of Hedley’s painting of Brownlow My Neighbour begs the question asked of Christ: ‘Who is my neighbour’. There is accumulated richness and contests of interpretation in the understanding even such relationships. In other sections relationships to another or others remain of importance, in, for instance, considering social cognitions of categories of person related to a place like an artist’s studio, wherein paintings convey meaning about persons considered wrongly as character ‘types’ in art history such as the meanings attached to artist’s ‘models’ as a ‘type’. These frequent art history, often in pernicious ways, especially in relation to male artists, such as Pablo Picasso. I will touch on this in relation to a comparison of paintings by May Potter and Leon underwood below in contrasting a female and male take on the painting studio.

These therefore will be my headings:

- the spaces they use;

- the self-image they prefer to show and;

- the meanings they attribute to the process of creation.

- The spaces artists use.

Liss Llewellyn’s category ‘working spaces’ (which they also gloss at one point as ‘different artistic milieux’) is an excellent one. Dealing with such spaces is justified in terms of the history of art because of the considerable debate between artists that, after the virtual disappearance of the craft workshops (with their structures of apprenticeship) of the Renaissance and Baroque artists, that sometimes resolved into debating a choice between painting en plein air or in a private studio of some kind. This is illustrated, for instance in differences between Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin when both, for a short time, lived in the Yellow House at Arles. The spaces used for work could clearly be ones inside or outside the walls of a building, and that building could be as formal as a school of art or someone’s sitting or living room, in one case (as we shall see) a barn and not just in Charleston. But outside places were often re-created in drawings en plein air and realised in studios. Of course then the spaces, especially the outside ones could become multiple in their signification or genre, especially when they housed a person chosen as a model and someone the artist loved.

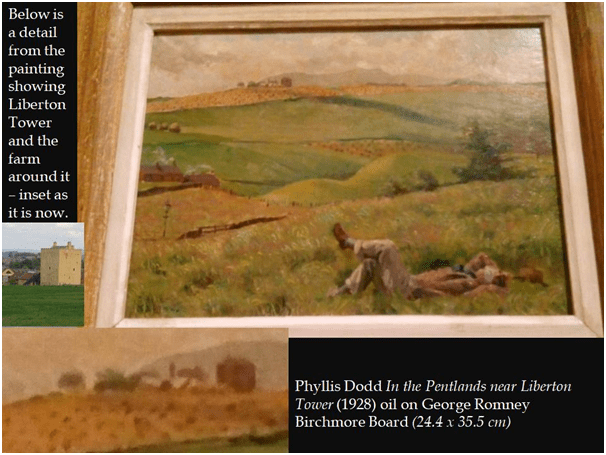

Geoff and I were thrilled to see for instance an apparent landscape of the Pentland Hills near Edinburgh, now nearly entirely with all the fields shown in it built over, that included in its distant detail Liberton Tower, in which we once had a week’s holiday in its mock medieval interior decoration (you know the sort of thing – medieval chargers made up of resin to use as plates). But it was painted By Phyllis Dodd (1999-19950 band had her husband, the artist, Douglas Percy Bliss, in its foreground. The book notes that Bliss himself also painted the self-same scene. The fact that this painting covers many of the categories invented by Liss Llewellyn is telling, since it is of a specific person she loved, an artist, and a space she used to create and so on.

An exploration however of the nature of the gaze defined by the artist’s eye is however is clearly a function of this painting, not least in the invitation for the eye to roam the hills, detect its blind spots and occlusions and to strain out to the distant buildings whilst being brought back in the forefront to this one clothed body in all its nonchalance. It’s a lovely painting in which space is a theme and for which the fifteenth-century keep that is Liberton Tower extends from a space in geography to a space in time. For us it marks a point where in the wake of another war with Germany, artists still celebrated their command of large spaces, as if they owned and guarded them and in which they, hats off and exposed to the sun, they were ‘free’. However, also in 1928 she married Bliss and as his wife turned her attention from paint to dusting his house. For women the freedom of 1928 was to be discovered to be a kind of mirage perhaps.[6]

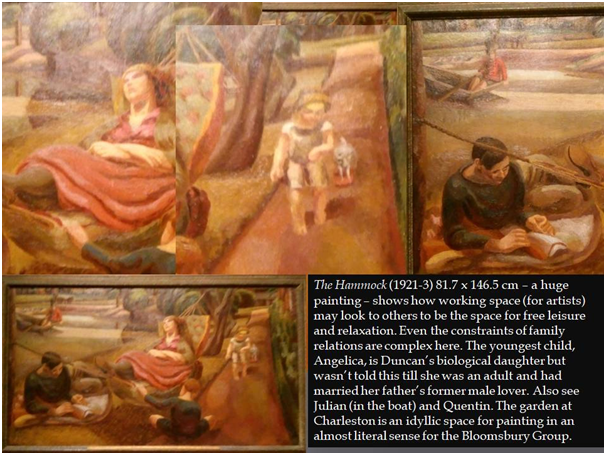

This is not the case though when the inherited and unearned wealth and social status of the artist is greater, although not irrespective of gender. Nevertheless when Duncan Grant painted The Hammock in 1921 to 1923, she was the more lauded artist and this painting therefore is of an artist and a family member and lover. But the garden at Charleston here is an expansion of the artist’s interior working space into the outside and declares freedom not only from domestic drudgery for Vanessa but also in child-care and development. The young man in the painting is the psychologist W.J.H. Sprott (and one time lover of Maynard Keynes and perhaps Duncan Grant), whom acted in his impecunious youth as tutor to the Bell boys – sons of Vanessa’s legal husband, Clive Bell – Julian and Quentin.

Though there was freedom from role and convention across gender here, relatively, Angelica, the youngest child here was a victim of that very parental freedom, being allowed to believe that Duncan Grant was not her father until eventually she married his former male lover, ‘Bunny’ Garnett.

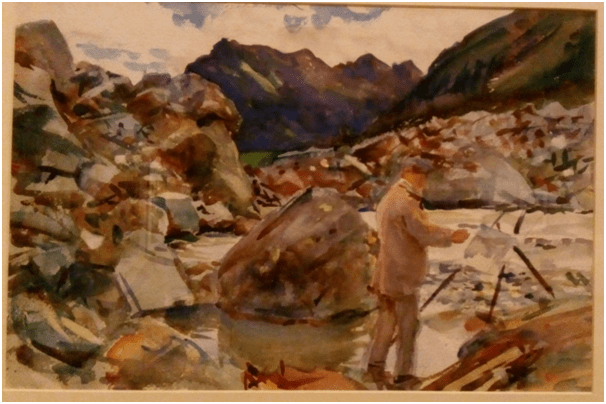

Space is a complexly informed thing for these artists we can see I think from these examples. This is not the less so in paintings we will encounter in other categories in this review. When a painter chooses a large natural space in which to show himself painting, even in a preliminary piece such as the pencil and watercolour first state piece by John Singer Sargent (again I found one owned by the Laing) named A Glacier Stream in the Alps (1904). It is as if earth and its processes so visible in such a context of a seemingly primeval glacial context and its melt as visual domains that were entirely the artist’s space and belonged to him, as if he created them. This is an allegoric notion in painters of the time to which we will return.

Before we look at interior spaces used by artists both as subjects AND venues in which to paint, we might consider the role of windows that access exterior space through a frame, in that they provide a metaphor for selection of subject. There may be numerous reasons for this and these may differ for painters as different as say Bonnard, Matisse and Picasso (all of whom exploit window frames as a means of divided the picture space and either increasing the depth of space or ironically point out the flatness of all picture spaces. Martin Gayford has recently said of Lucian Freud, for instance, that all of his landscapes ‘were views from within a room, as he disliked working outside’.[7]

Only one painting (by Harry Bush – above) in this exhibition might be appropriate (though there are many more – and more interesting ones in my opinion – in the Liss Llewellyn book) and even this does NOT make it evident it is a view through the window of an artist’s studio or other home painting space, though apparently it is, and this is claimed its title. Yet the idea of painting a community from which one is literally separated – as seen from indoors – is a fascinating one, and fits the ideology of suburban London with which Bush is associated. They include often people doing everyday tasks – here a man in his allotment or garden in Merton, where Bush lived.

In painting their own studios too, artist may be led by ideas that characterise the meaning of such spaces to them. In Malcolm Drummond’s painting of Walter Sickert’s studio the oveririding concern is the depiction of an entirely masculine space, in fitting with the self-conception of the Camden Group of artists of which he was one, with Sickert of course, and the three gentlemen pictured (identified as J.B. Manson, Spencer F. Gore, and Charles Ginner by Paul Liss)[8]. All were founder members of the group. The painting itself constructs the studio from bold geometric shapes and out of strong colours in fitting with the Group’s post-impressionist ethos.[9] The angularity of the spaceis not only masculine but aimed to manifest a work of construction which draws attention to the hands of the Gore and Ginner, both held away from the paintings and more visible than their faces. This is an art of constructed or manufactured meaning not of optical illusion. It contrasts brilliantly with Belleroche’s studio, which is feminised by the presence of the model, Julie Emilie Lisseaux, whom he was to marry and who also appears in a lithograph of the studio from the same year as the model of an easel painting veiled, although it would appear to be in white or a light colour, rather than the black in this oil painting.[10] Her presence in black gives a kind of semi-religious feel to the painting feeding of the church architecture housing this studio. This may have been intended to create ironies since one of the posters – on the viewer’s left – on the wall is identified by the Laing curators (and one can see this even in the small reproduction) as La Revue Blanche by Toulouse-Lautrec. There is a commentary possible here on the transformation of art from religiousritual to everyday recreation that pre-dates of course the more serious and more male-centred ideologies of the Camden Group, since Belleroche, like Singer Sargent who was his friend, both met as apprentices in the Paris studio of Carolus-Duran, and both influenced too by the impressionists. Space is then about the meaning of the creations in which it is shaped.

Size might of course betoken a painter’s sense of the import of their creative talent, as I hinted with Singer Sargent returning to the origins of the world in the Alps. In a painting added to the exhibition by the Laing by Ralph Hedley, a Newcastle painter whose work is well represented in the city shows John Graham Lough, another North Easterner – born in Consett – creating his statue of the Greek athlete, Milo of Croton. As the Laing curators tell us (Hedley is not a painter represented in the Liss Llewellyn guide) Milo was used as an exemplum of hubris – excessive human pride in the face of the Gods. The almost comic nature of this painting in my eyes suggests a kind of semi-satirical purpose here in which Lough’s own hubris has made him increase the space in his studio, by knocking in his ceiling, to make space for the overblown grandeur of his conceptions. The consequences of hubris here however are not the Furies from Greek tragedy but Lough’s furious landlord and his lawyer, which the Laing curators identify as the very famous Henry Brougham. In contrast Hedley’s picture of a Newcastle artist who was a close ally, Stephen Brownlow, (this picture is from the Shipley Gallery collection) emphasises the modesty of the artist’s studio and the careful attention to everyday truth – even in life relations since he seems to have supplied a cover for the gentleman in the background (presumably his customer) to keep him warm in a cold room. Perhaps though Hedley here contrasts the painter from the North East who felt he had to become an artist in London and among wealthy patrons, if at all, and the modesty of Brownlow, and of course himself, since his studio adjoined Brownlow’s in Bridge Street, Newcastle.

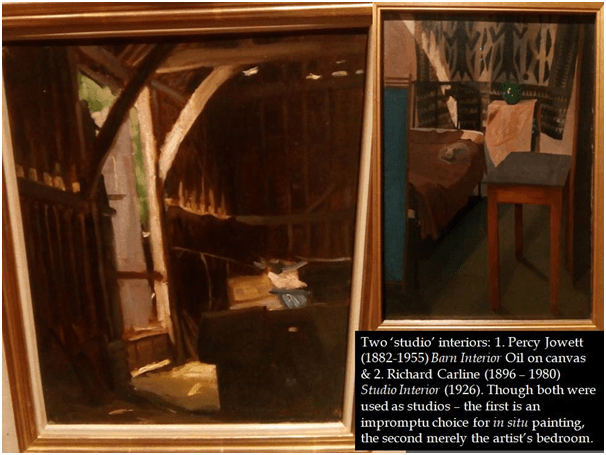

But the concept of an artist’s studio is a transferable feast perhaps and of lesser importance in a period in which we see an artist as defined by something in their own make-up as a person than the apputrenances associated with art. Two pictures in this exhibition tell of this. The first by Percy Jowett and the second by Richard Carline.

Jowett is, people say (see link above), better remembered as a teacher of art and administrator of art teaching than an artist. But Liss emphasises that for him a ‘studio was a moveable locus taking up any space that might enable enough light for the work. The painting Barn Interior emphasises morning light falling from the east, I take it, from an open door capturing how Jowet, aiming for somewhere to complete paintings done in situ on his travels seemed selectable as an ‘impromptu studio’.[11] Carline’s space seems painted almost to show that any space – however cramped and impractical, can be a studio for a true artist of the everyday scene. The everydayness is emphasised by the cat on the artist’s bed. The meaning of this space can be contested, it appears, by any householder member.

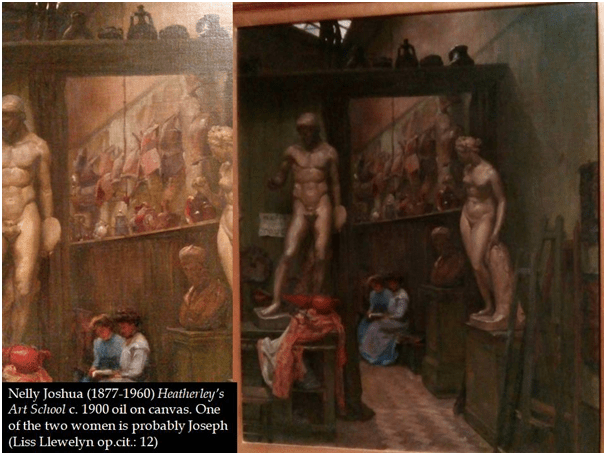

Of course the atelier or workshop studio may also have lived on in the increasing prominence of the art school workshop and, even in British art, this remains a subject. This is important largely in the concept of the ‘life class’ in which figurative artists were introduced to drawing figures anatomically from nude models. It was late in their history before such spaces admitted women, who were not before that expected to draw full figures but only faces. An early introducer of women to such spaces, was the private art school, Heatherley’s, in London. A painting I loved from this exhibition was one by Nellie Joshua, who trained at Heatherley’s. Her response to the space and to her self-conception is as encapsulated in this painting, i belive, as Sargent’s command of the glacial environment in the upper Alps. What Johua emphasises is her relation, since Liss Llewelyn believe one of the besmocked women in the picture, somwhat dominated by the traditions of this teaching space nevertheless, is Joshua. Indeed the other female might be her sister, who was also a painter trained in life forms at Heatherleys.

Seeing the painting exhibited is a joy. The two female artists are located at a focal point of the painting, wearing the smocks expected of Heatherley women artists and in conversation. Yet they also sit somewhat askew in an aisle that is kind of avatar for a reduced representation of the path to a vanishing point. This detail forces attention on the manner in which male artists have dominated the portrayal of nude form – both in men, using a classical model (it bears a discus) and what appears a clerical bust behind the female nude, and, of course, the predominant female nudes in later art history. But, I asked myself, why is the blue of the smocks contrasted with the scarlet and red colour of female clothes under the feet of the male statue? Clearly Joshua had a choice about the inclusion of such a dress and it takes the form of an icon, in my mind, at least, of discarded feminity as described in their patriarchal social milius, even with the hint of a sexualised women, against their chaste blue dresses. The mirror above them reflects the room behind the viewing point of the picture hung with male armour. Otherwise the room shows different traditions in art and craft further surrounding the women with their history of being in the male possession, even down to tools of art such as the easel on the viewer’s left . It is, whatever you thinking about how it reflects the ‘self’ of a female working artist in the modernity of 1900, a most intriguing painting.

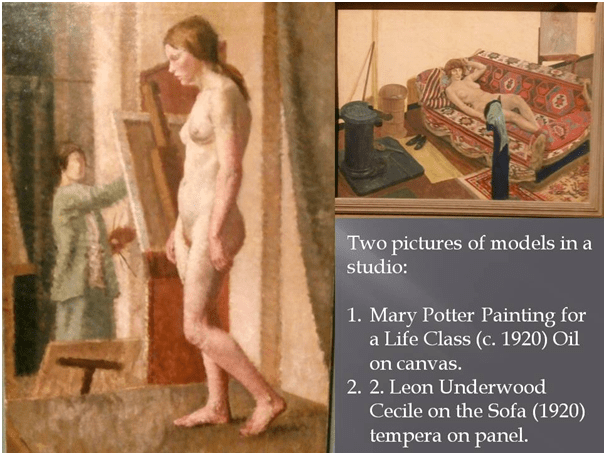

In Heatherley School of Art again (as in other paintings above) we see how choice of self and/or other persons in a painting relates to the interaction between them and the meaning of the space in terms of artitic identity and beliefs in the role of the artist. We do not really KNOW whether Joshua is in this painting. All we can know for sure is that she had a reson for choosing persons who were identifiably female artists in her decision-making about how to design the form of the painting and the significance to larger issues about art and artists that might flow from those choices once made and executed. In the next section I want to look further at a few paintings where the choice of persons seems significant to the artist’s relationship to them, whether that relationship is cognitive or emotional. For instance, the best comparison to make of the paintings of studio settings which follow relate to the gender of the painter: one is by a male, the other a female artist; respectively Leon Underwood and Mary Potter.

Studios are places where models disrobe to become objects in a life class. During the history of art female models (only records of women serving heterosexual male artists – notably in the twentieth century, Picasso – are usually referred to in the tradition of the discussion of artist and model relationship, perhaps in awe of Pygmalion). I do not know the relationship between Underwood and Cecile in his painting (although I do know he painted her portrait bust in 1922 as well), if any, but it is certainly a painting which fits into the tradition of male paintings of female nudes in my view, with the exception perhaps of the care taken that her genital area is covered in the painting. However Cecile is, in my eyes at least (though a queer man), offered to us as much as an object in a man’s studio as is the sofa, carpet and stove. Considerable attention is drawn by carpet and the trow on the sofa that in fact distracts from the nude. However, despite this, Cecile’s body is clearly made to pose in a way that suggests her availability to the male gaze out at which she looks out, not directly but, more worryingly, ‘up to’. From her reclining position and the self-exposure caused by the placing of her arms and legs, Cecile attracts the heterosxual male’s gaze, almost as a condition of her being, as conceived by Underwood at least. In such art the gaze of the artist standing at his easel is synonymous with the viewing position offered to the viewer, whatever the sex/gender of that viewer.

This is patently not the case in Mary Potter’s painting since an artist is depicted behind the model. Of course in a life-class there will be more than one artist viewing the model (indeed other artists’ easels are visible even behind the model) but, as I read this painting, the visible female artist, with a face blurred from focus and unidentifiable in large as an individual person, other than in the knowledge that she is a ‘woman’, signifies the absence of a predominant male gaze. It is a sign, in my eyes that we are offered the model’s body to a gaze, of either sex/gender, that has no sexual interest in the body of this model. Moreover, there is no gaze from her out to any viewer we can identify with. Of course the body is still presented as an object but our ability to intuit a subject in it is much more possible, not least because of the casualness (perhaps even unplanned inelegance) to the pose she takes as if, apart from the contraposto conventionally demanded, it is decided by herself. Even the fact that her genitals are visible will not make this, I believe, a painting inducing a sexual response. In the next section however we must directly confront the artist themselves, looking at the self-image each prefers to manifest to viewers of their work, if only for a particular painting.

2. The self-image these artists make available in their paintings.

The self-image of a painter may well be related to places, especially to studios in which the identity of the artist becomes our primary awareness of this personality, caught in a moment of creation as it were, as in Velasquez’s Las Meninas. Ralph Hedley is no exception, with a bearing very reminiscent of Velasquez’s. However, this studio portrait overtly champions Hedley’s, and the extension, all (male) artists as gentleman, whose status is not bound just to work or to patrons but to the accoutrements of a fine gentleman of deserved status and the ability to maintain that appearance. The use of a dressing table complete with the accessories of a gentleman’s evening wear as he steps out is to me incongruous but also defining of a conception of the painter as a professional gentleman whose life is as defined by the society he will deserve to keep as his painting activity.

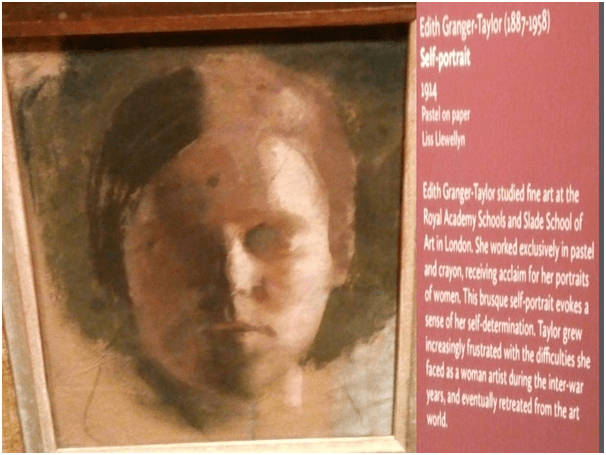

Yet, as we have seen the studio paintings of the two female artists I have discussed above – Nellie Joshua and Mary Potter have almost deliberately reduced them (neither artist very clearly identifying themselves as being represented even) to a figure only recognisable through their work. This might suggest a greater interest in these women in the fact that their role matters mainly as a signifier that that role, as an artist, was now available not to just to themselves as individuals but to all women. But it also potentially signifies a felt need in these women to reduce their significance as an attractive appearance – the role to which, it might be thought – a patriarchal society reduces women, robbing their work of significance as was never done to men. The female artist in Potter’s painting is literally effaced and perhaps this is because it is notably the face to which, when it is not to sexual parts as in pornography, a woman is reduced in male art. I cannot know the motivation of a very great portrait artist in her 1914 self-portrait. Her features are obscured here even to the point of deliberate erasure – as if the reduction of her to a mere attraction to the male gaze, still possible in earlier beautiful self-portraits, was being resisted at the same time as a beautiful, haunting and innovative painting is produced.

Male self-images meanwhile were diversifying in interesting ways from the evidence of some of the self-portraits in the exhibition. Edgar Holloway, for instance, according to the National Portrait Gallery webpage on him, used his interest in Augustus John’s work to likewise use ‘self-portraiture as a means of exploring different aspects of his personality, sometimes adopting an alternative persona’.[12] In the two of the many in the exhibition I have chosen Holloway is clearly playing these role-play games with his own image, but always (in others as well) with a concentration on his personal attractiveness, which leads to a prominence given to the shaping of his face, especially nose, lips and the finely defined facial features between those highlights. This is no gentleman of the Hedley variety, evening wear the ‘topper’ in the inset drawing. The larger piece emphasises a kind of boyish, but also rather rough allure. I find these games with gender role as keen as those that young men of the Renaissance played with their image, though profoundly un-Victorian.

If we contrast this piece with the Norman Cornish piece, the apparent similarity soon disappears though each was probably aware that their status as self-taught artists gave them a kind of freedom in self-presentation. Cornish wear a genuine handsome young male working-class identity with pride (he was still at the time of painting working primarily) though shown in loose-fitting casual dress not unlike Holloway. For Cornish knew he was unique – to be an artist while still being a miner. Such diversities however come somewhat dearer in cost to personal wear and tear than the costume changes that alone mark Holloway’s shows of varied self-images.

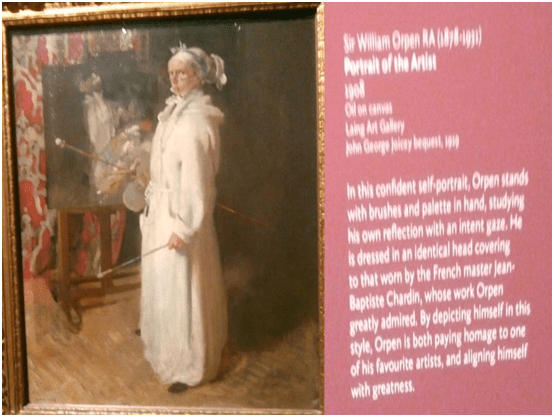

This play with self-image contrasts I think with the case, in another wonderful painting owned by the Laing, in Sir William Orpen’s Portrait of the Artist, in which the art plays the role of an old master he admired, Chardin, but with a conscious play with a more modern set of stylistic traits that Chardin would not have used. It is also clear that Orpen is happy to look ridiculous, by the standards of his age and time, and to rejoice in the arch playfulness that involves.

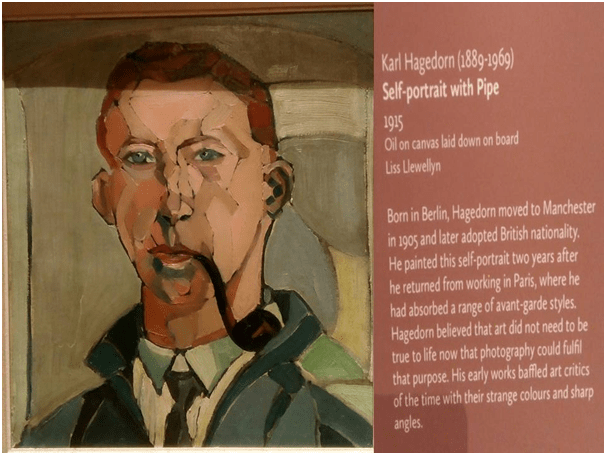

Karl Hagedorn however, though often mocked for how his self-portrait made him appear, uses the techniques he has taken from mainland Europe, from cubism and fauvism both, to type himself as a modernist artist, rethinking the means of visual presentation. I liked this painting partly because of its modernity and its rather ironic, in my eyes at least, manner of presenting a stereotypical male, complete with pipe, trench-coat and casually worn tie.

These people all present themselves as creative artists with a keen sense of the fictive play that painted or drawn self-portraits allow. I wonder if this led Liss Llewellyn to make their final category in this show, ‘Allegories for Creation’, for allegory is a kind of role play where ideas and values take apparently solid presence and enact their meanings. The Laing Show severely cuts the number of such paintings available to them from Liss Llewellyn, and although this means fewer very intriguing paintings it emphasised those nearly great ones, that surprise because so unknown relatively, that were hung. This leads us to our final section:

3. The meanings the artists attribute to the process of creation.

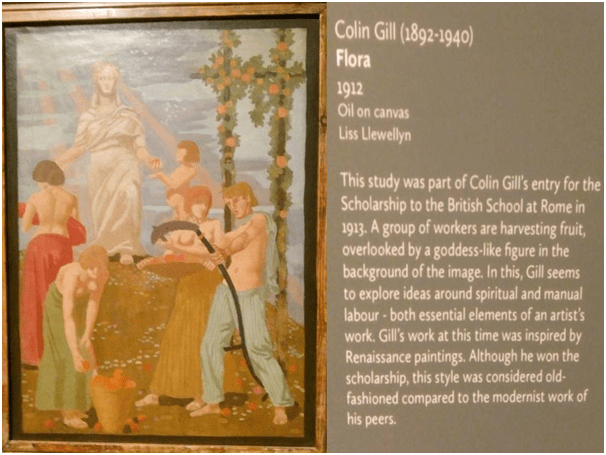

The cut made by the Laing has emboldened me to cut my own selection, for one another look some of this work is deeply conventional and lacking in meaning otherwise, such as the pieces by Colin Gill. Look at the 1912 Flora for instance, which I find not only ‘old-fashioned’ as thought by examiners at the British School in Rome on its presentation to them but rather tiresome in its faded look and over-conventional and over-simple allegoric imagery.

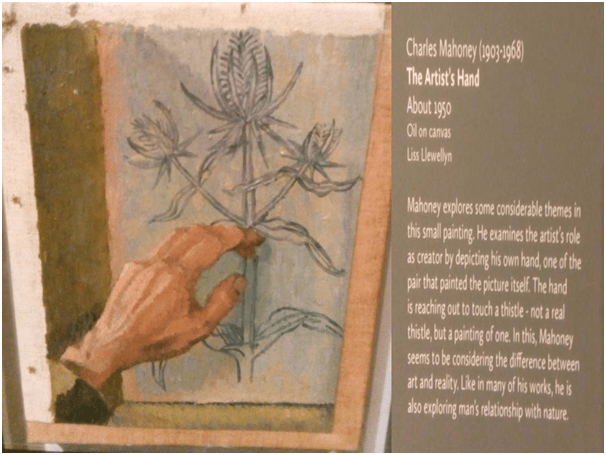

Perhaps unfairly I find too much of the same in other offerings. But two paintings in particular shocked, surprised and enthralled me, even when, in the next, the idea behind them are somewhat tired – the relation between the painted image and the working reality of a painter’s life of re-creation. The first painting is Charles Mahoney’s The Painter’s Hand. For me, this works because of the solidity of the hand, with signs of a kind of premature age, and the refraction the finger-tips seem to undergo as they penetrate the illusory picture-surface. This feels strong in part because the picturing of the thistle shows no attempt to achieve a solidity that gives the purpose of the concept of a picture-surface when we talk about perspective. This thistle is so flat it has never aspired to the life of any real model. As a result, there is something quite complex achieved that cannot be transformed into words that have clear meaning at all. The work of the artist is not seen as mysterious but it is seen as transformative. But the transformation is not a matter of ‘magic’ or other vague concept but of work and the experience of age. I love that painting.

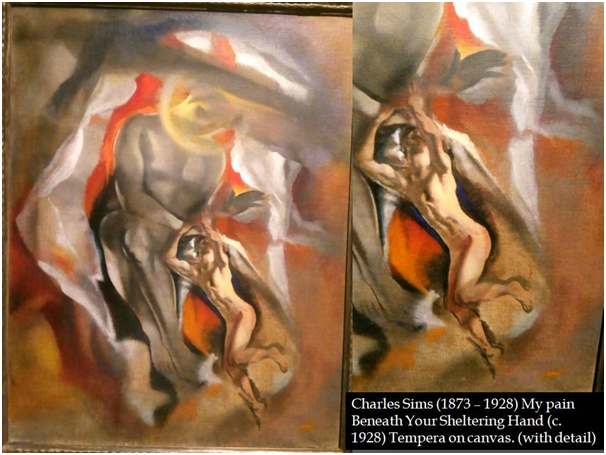

The second painting is more melodramatic in a way though it feels cruel to say so. That is because the pain it names led to the suicide of the artist, Charles Sims, very soon after its completion.

Whilst the God painted in this scene is meant to be paternalistically caring, its grey flesh looks deathly rather than ethereal, in contrast to the fully realised flesh colour of the Sims self-portrait. The hand that is claimed to shelter also seems to be suppressing any flight made by that beautifully proportioned naked man. I sense him being pushed down and back by the paternalist to which he raises his hands in almost a plea. Indeed my first reading of the title was that what the hand sheltered was not the man and his aspirations but the ‘pain’. This god fosters ‘Pain’ and gives it meaning. Is this ghostly God Death in fact? If it is, it is not removing pain but merely pushing it under. The glory in which Sims sits feels rather more infernal than celestial, more like spilled blood than released spirit. And for this reason, I loved this painting.

I cannot back this reading by evidence – there is little enough to support any reading at all. But I prefer to love it for the wrong reason i suppose. That is a good place to finish this very selective overview of my day, the reading that followed and my reflections. Art surely is important to us because it promotes reflections that enhance the importance of contemplation of the complex visual image and the ways imagery touches on other domains of life and art. I do recommend the exhibition. If you see it, you will love it, whatever you think of my reflections. But before I go I have added a postscript on the richness that is there for visitors to the exhibition by continuing to a new arrangement of the permanent collection, which i believe to be a wonder.

A postscript on the Laing collection celebrating its richness

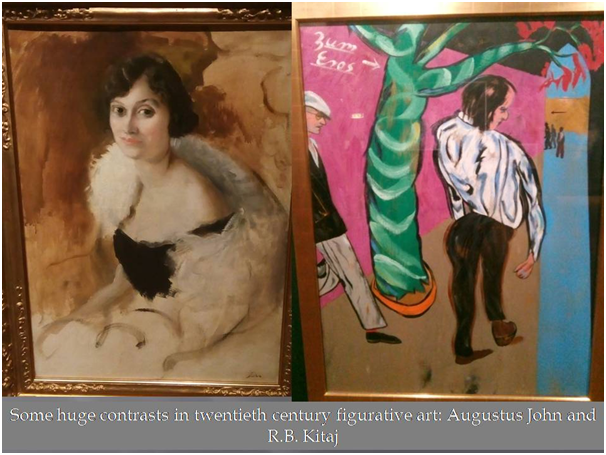

After looking at I think visitors would be advised to continue to the rooms in which the whole Laing collection is retrospectively celebrated currently in a selection of its great works from ‘sung’ and ‘unsung’ artists. Of course famous ones like the 1886 William Holman Hunt visual recreation of Keats’ Isabella and Pot of Basil and John Martin’s spectacular The Bard are there, but so were ones of which I was not aware. But the overwhelming impression of a quick survey of these bounteous rooms was of the infinite riches of a less than patterned glory that mirrored my impressions of the buzzing confusion of developments in art during my childhood and young adulthood – such as the huge contrasts in figurative art both in content, form and manner of painting. Harmonies in colour and tone in Augustus John’s portraits give way to overt violence of colour contrasts in R.B. Kitaj. It is difficult to see such broad brush-strokes of difference in a single exhibition usually.

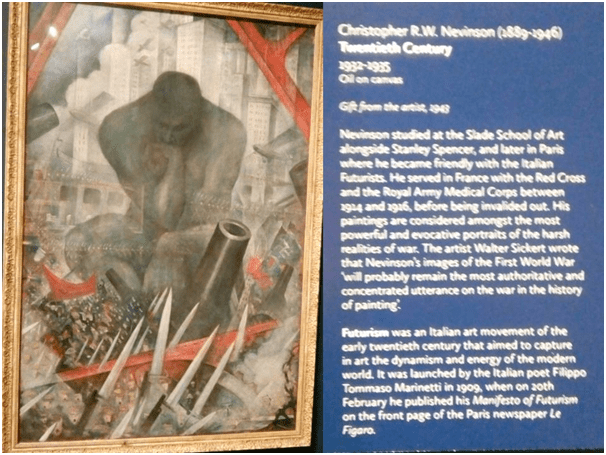

And some pictures in this exhibition might not have seemed as significant as we should now see them and I think this will be truer as people reassess the work of Christopher Nevinson: particularly that star in the Laing’s possession his allegory of the First World War, which is still badly served by being discussed under the heading of an English offshoot of Italian futurism, with the fascist tendencies within that movement. Nevinson’s statement on the First World War seems to me of the stature of Wilfred Owens’s poetry.

For me too this collection matters because its principles of selection have never been purely aesthetic – whatever such principles might mean. Hence a beautiful painting can be accepted in 2020 that actually explores a human issue, such as the nature of the loving vision (also explored I think in the exhibition discussed above, of an artist of their chosen model). Mike Silva’s 2020 painting of Jason comes without commentary and I do not know more of it than the understanding that he painted specifically his friends and lovers. Julie Milne argued that this acquisition was about more than the forms and styles of art but also about the duties of public collecting in:

… ensuring there are pictures on the walls representative of people of all backgrounds and as a trusted public institution we are committed to addressing the kind of erasures, omissions and incomplete narratives that are inherent in many public collections of British art.

I, for one am grateful for this. True Kitaj addresses some aspects of queer experience in the picture I have already shown and within it is surely a portrait of David Hockney, his friend, for Kitaj himself was always seen as a forerunner of a queer identity that was not specialised to that of lesbians and gay men but about the spectrum of non-normative sexual expression. But the Kitaj painting refuses a normalised queer experience – indeed that might be a contradiction in terms – whereas the Silva painting raises the problem of how the artist’s gaze expresses love and desire for its subjects and models of love and friendship.

I suppose love emerges from the angle of vision (which is not painterly and cannot leave space for an imagined easel) but it is also carried by the visceral touch of light on skin from a direction other than that of the viewer’s gaze. The hand resting on Jason’s torso is his own but it provides the mechanism of how this picture animates the haptic qualities of our gaze on it – a desire to stroke or caress that is also forbidden by the model’s non-consent as he sleeps. It is most beautiful and speaks to an approach to the body that differs from that of classical and neo-classical art, where the touch is only ever invited and forbidden in a starkly antagonistic way, like that of pornography. I have tried here to say what creates what, for the collection above, Liss Llewellyn call ‘the frisson that suggests the artist was in love with his or her subject’.[13] Maybe that shows that the mutual nature of the gaze between viewer and viewed has always been an important aspect of art, since the cusp between what is public and what is private became problematic for our culture as at the same time it was a validated necessity – perhaps from the eighteenth century.

All the best

Steve

[1] Quoted from the Liss Llewellyn mission statement – copyright page.

[2]Paul Liss in ‘Foreword’ to Sacha Llewellyn & Paul Liss (2021: 9) ‘Portrait of An Artist’, London, LISS LLEWELLYN

[3] Ibid: 9.

[4] Ibid: 9.

[5]Paul Liss in ‘Foreword’ to Sacha Llewellyn & Paul Liss (2021: 9) ‘Portrait of An Artist’, London, LISS LLEWELLYN

[6] See Dodd, Phyllis, 1899–1995 | Art UK

[7] Martin Gayford (2021: 67) ’Enamel-smooth and astonishingly intense’ in David Scherf (ed.) (2021: 69) Lucian Freud: The Copper Paintings Hamburg, Germany, Less GmbH, 59 -67. My review of this book at the link in this note.

[8] Sacha Llewellyn & Paul Liss, op.cit.: 24f.

[9] Ibid: 25

[10] See ibid: 18f.

[11] Ibid: 44

[12] National Portrait Gallery webpage available at: Edgar Holloway – Person – National Portrait Gallery (npg.org.uk)

[13]Paul Liss in ‘Foreword’ to Sacha Llewellyn & Paul Liss (2021: 9) ‘Portrait of An Artist’, London, LISS LLEWELLYN