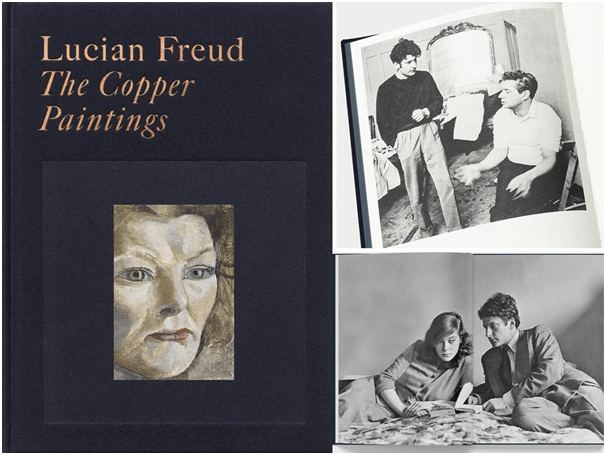

‘… if I concentrated enough, the intensity of the scrutiny alone would force life into the pictures’.[1] An attempt to find the ‘distilled essence of Lucian Freud’s art in a small sample from his early art wherein technique, style and meaning are a function of qualities the artist demands of his the interaction between the viewer’s gaze on his subjects and those subjects’ illusory ‘gaze’ on and into their viewers. A blog on David Scherf (ed.) (2021: 69) Lucian Freud: The Copper Paintings Hamburg, Germany, Less GmbH

What exactly do we need from a book that is costly and is yet a very brief in text and even in illustrations. The publisher promises us a previously unseen photograph of Freud’s portrait of Francis Bacon in situ at the Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin from 27th May 1988 – the day on which this painting was stolen. But although that photograph tells us a lot about the sparseness of the manner in which paintings could be hung at that time, that may not justify the price of the book. Moreover, though stolen in 1988, this book still follows the request made by Freud that this painting never be reproduced in colour until its return – and that return has still not occurred. I feel fortunate in that respect that I have the catalogue from the Hayward Gallery at the South Bank Centre in 1988 just before it went to Berlin, the last colour reproduction in the UK I believe.[2] The subtle colouring is just amazing.

So if it is neither of these possible highlights and I still absolutely love this book, why is this? The text of the book is, as I have said, sparse in quantity, but it richly illuminates these paintings in showing how the meanings they yield interact with the novel media used in their making (novel at least for the age) and style, around the concept, applied across the field of optics, idea and emotion of ‘intensity’. There is nothing new in Scherf’s observations that Freud was known to look intensely at his models over many sittings over a very long duration – Martin Gayford has already written about this brilliantly in the narrative covering his own experience modelling (though fully dressed) as a model for Freud. There is a banality about saying that for Freud intensity ‘meant penetrating to the innermost being of his subjects’, since the phrase sounds like so much rather empty rhetoric we read about art and artists. But he is better when he gets to basics with regard to the how and why this speaks to us in gazing at, and being, apparently though in illusion, being gazed at back, by those subjects, which he calls in the case of Charlie Lumley, a copper I saw at the Tate Liverpool retrospective, ‘a staring contest’. Elaborating that point somewhat objectively but with accuracy about the strange framing of the subject in the narrow shallow space of the picture frame:

… one senses how physically close Freud got to the sitters and the unease it caused. The heads completely fill the small plates, and the sitters squirm before Freud’s stare, their faces emotionally withdrawn, their eyes fixed on the floor or a distant point as they wait to be released.[3]

The reproductions of full paintings and details from paintings that follow illustrate this well and are in themselves enough to justify this book, together with the catalogue of the existing coppers known to us.

But I feel that the essay commissioned from Martin Gayford an even richer treasure, though I rarely feel that in the presence of commentary by others. For Gayford takes a brilliant approach to the copper paintings through querying why Freud chose that unusual’ technique in the first place (‘among major artists unique to Freud’), and why it might ‘fit perfectly into his stylistic trajectory’.[4] Just as copper painting is an archaic survival of the seventeenth century mainly, so Frank Auerbach chose to characterise his style at this time in another archaic concept, suggestive of Elizabethan and Jacobean England, ‘limning’.

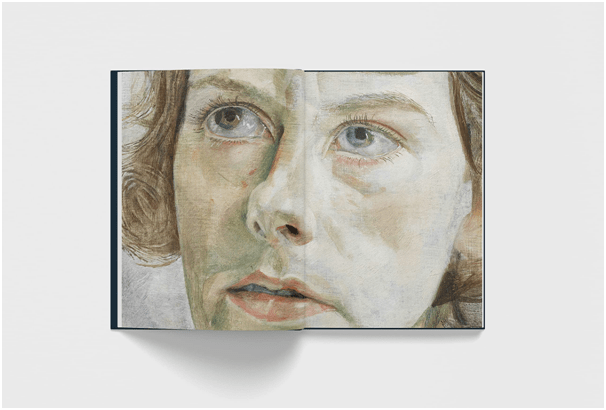

Often referring to the art of miniaturists like Nicholas Hilliard, the copper painting often surpise when one sees them, as this year (see blog from this link) they did me in Tate Liverpool, by their small dimensions, which adds to their sense of intimacy as they draw in the viewer to make out the extensive detail in them. Freud had to get physically close to sitters like the East End gangster, Charley Lumley (Boy Smoking). And so must the viewer. We see every blemish on the skin of Lady Elizabeth Cavendish in Head of a Woman (1950), as the reproduction of detail from that picture almost painfully shows in this book.[5] Am I the only one moreover who thinks one is almost invited to touch the lips of Charlie Lumley, perhaps with one’s own lips, whatever dangers and costs this might involve.

Intimacy is there but also discomfort and a degree of fear at the consequences of the social transgression which viewing at this proximity must make most people feel. We are, Gayford says, ‘deprived of the normal distance which divides us from people we meet’.[6] And the other thing I noticed in looking at this and other early Freud was the perfect finish of their flat surface, as if that artifice was needed to stop us feeling that we are in fact nearly touching upon the flesh of another. This is not the manner of later works where fleshly effects call forth layered impasto work. Gayford claims there is a Surrealist aspect to the glassy precision of these portraits, though combined with exaggerated feature – notably the eyes and the corrugations of Charley’s lips. As Gayford says he was at this time aware of other surrealists and that some paintings recapitulate ‘the close focus and hypnotic quality of the drawing of Christian Bérard’.[7]

What we have in Gayford’s essay has limitations consciously made – they admit we are at the beginning of an exploration of this painter, whose intensity we find (or at least I find) disturbing. And it is an intensity we can use to describe our visual interaction not only with persons but things, like a box of strawberries or a potted yucca’s base. How and why do we see those as intensely held in the gaze and as perhaps conscious of being so held and constrained? I do not know. Again it has something to do with both the proximity and partiality of viewing and framing. Even objects want to push back from us I believe. But it is in those exaggerated eyes that resist us seeing facial blemish as closely as we are intent on doing that I find most challenging. Look again at Elizabeth Cavendish.

This is a wonderful book. I love it.

All the best

Steve

[1] Lucian Freud as cited in David Scherf (ed.) (2021: 69) Lucian Freud: The Copper Paintings Hamburg, Germany, Less GmbH

[2] The British Council and Robert Hughes (1987: 11) Lucian Freud: paintings, London, Thames and Hudson.

[3] David Scherf (2021: 9) ‘Introduction’ in David Scherf (ed.) op.cit.:7 – 11.

[4] Marrtin Gayford (2021: 59, 60 respectively) ’Enamel-smooth and astonishingly intense’ in Scherf (ed.) op.cit.: 59 -67.

[5] Scherf (ed.) ibid Plate 4 and detail on fold following.

[6] Ibid: 63

[7] Ibid: 67

8 thoughts on “‘… if I concentrated enough, the intensity of the scrutiny alone would force life into the pictures’. Finding the ‘distilled essence of Lucian Freud’s early art – where technique, style and meaning are a function of qualities the artist demands of his the interaction between the viewer’s gaze on his subjects and those subjects’ illusory ‘gaze’ on and into their viewers. A blog on David Scherf (ed.) (2021: 69) Lucian Freud: The Copper Paintings”