‘Penelope’s scepticism is my invention, …’.[1] ‘I follow Apollonius in having Jason tell Medea about her cousin Ariadne – in fact I have made Jason’s economy with the truth much more obvious than it is in the original’.[2] This is a blog on some of the reasons why writers and artists who are also women choose to retell stories recreating the ‘ancient mythological’ compendia modelled by men, like Ovid at their best, amongst the ancients and later. A hymn in praise of Charlotte Higgins’ [2021] Greek Myths: A New Retelling Dublin, Jonathan Cape / Vintage/ Penguin Random House.

Peter Stothard (himself a seasoned reteller of stories from what we term ‘ancient history’) reviewing this book in the Times Literary Supplement is sympathetic of the need to re-create through them something which, ‘like all retellings of myth’ is ‘as revelatory not just of the mists in which recorded time began but of its own time’.[3] He mentions too that Higgins cites only three writers of the many engaged in the same project as herself: namely Pat Barker, Madeline Miller and Natalie Haynes. In adding that she ‘could have added more’ however, perhaps Stothard misses the point that the writers Higgins choose to cite are women, even though he is clearly aware that the main framework metaphor of this book – weaving on the hand loom – was chosen because weaving was essentially ‘the women’s work of the ancient world’ and a metaphor, even then for “women’s speech, women’s language, women’s story” (he cites these words from Carolyn Heilbrun . From that admirable wider awareness his assessment that Higgins ‘aim is to highlight the heroines rather than the heroes’ is rather reductive (in my ears at least). There is more to this wonderful book than a preference for stories about women, for it recasts all of the stories in its ‘compendium’ (those of men and women) with ideas of the constitutive effect of sex and gender. And not only that, it recasts them with lots of reference to the fact that sex and gender are not topics that support a notion of the binary division of men and women.

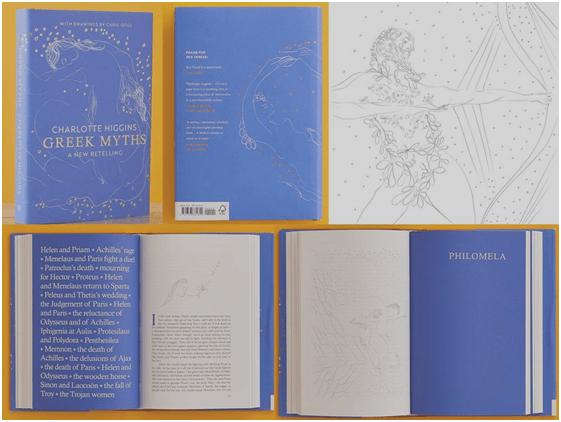

This is not only because the issue of transgendered being was important in some of the classical sources themselves – either in sophisticated or unsophisticated ways – but because her aim is to present a feminist perspective that refuses simple reductions of its theme of what women’s lives are. Her wonderful ‘Notes’ reveal the multiple sources (literary and visual examples from the entire history of these arts are herein included) often of each of her stories. In these she takes issue with the patriarchal assumptions of some classical writers in rescuing from evil association whole communities of real or fictive women. Some examples of this include, for example, the Bacchae (‘Dionysus’s female followers’) or Medea (who only Euripides may see as a child-killer despite a common belief that this role sums her up, Higgins tells us) in Euripides’ plays.[4]

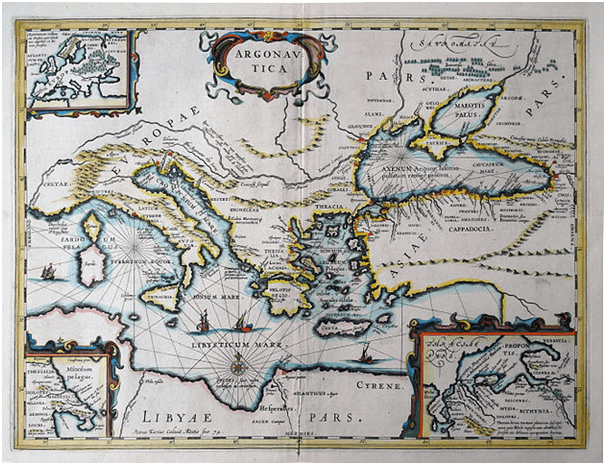

A key example to which I will return is the retelling and reframing of the ‘picture of female power’ in Apollonius’s Argonautica. In the latter the Lemnian women, who murder the males of the island to escape oppression, are represented as having a case not seen by Apollonius.[5] Higgins often corrects these representations in her retellings. Amongst these ‘Notes’ is also a discussion prompted by the work of ‘transgender classicist, Sasha Barish’, that some men use transgender issues to render ‘unthinkable’ the idea ‘of two women loving each other’. It is clear where Higgins stands critically in her apparently objective account of Ovid’s line: ‘…“femina femineo correpta cupidine nulla est” – no woman has been seized by desire for a woman, the poet asserts’.[6] This is a work that discusses complexities in sex, gender and and their interactions in choices about whom to love very seriously.

It is a joy to read this book because, unlike some of the other feminist rewriters she cites, it wears a modern contemporary perspective on women’s lives lightly but definitively and includes a nuanced respect to diversity within women. This is what allows it to discover difference in and between female perspectives, like those featured in the final section dominated by ekphrasis of the woven loom work of Penelope. This book is especially intelligent about this wonderful character, who finds the femininity represented by the goddess Athena as problematic as is the systemic patriarchy of the men in it and perhaps a reflection of their thought system. Yet Athena is the weaver of tales we confront first in this book. This like nothing else shows its complexity:

Did Athena even exist? The goddess had put thoughts into her head. At least, that’s what she’d always assumed when she had a burst of inspiration out of nowhere. … were they, in fact, the product of her own intelligence? The goddess had been born from her father’s head, supposedly, but that sounded implausible, to Penelope – like a male fantasy of how a child should be born, without any need for a female body.[7]

Indeed the role of both sexes in the reproduction of society – ideologically as well as in physical and biological substance– is a constant debate in the novel, not least in discussing the polity of Lemnos without men where an ‘older woman, Polyxo’ says, “Men, I fear, do have one essential function, however we might to produce children without them”.[8] Nevertheless that those same women had only rebelled ‘after years of mistreatment’ by men is never doubted in this story.[9] And the book is wise about the import of the ideological support in Greek mythology, as Anne Carson as often pointed out, for the persistence and naturalness of male violence and rape. It is too often necessary to write about this in the book given the fact that such behaviour is associated particularly with the male Gods, and particularly Father of the Gods, Zeus. The best example of this in my memory of the book however is the retelling of the rape of Proserpine by Hades, God of the Underworld, where modern feminist perspective on the contemporary effects of persistent male violence emerges in an extended metaphor like those used at their best in epic, in Edmund Spenser and John Milton even, which captures Proserpine’s unsupported vulnerability as one continuous with the fear of rape in lonely and dark places of twenty-first century women.

A pale narcissus nodded in the breeze, throwing up its delicate scent. Bending to pluck it, she felt a sudden chill, as if a thick cloud had passed in front of the sun, and with it a pull of anxiety. It was like when you walk alone at night along a city street and sense the tap of footsteps behind you. You walk faster, you look straight ahead, and all the while you know it may be nothing, nothing at all.[10]

This is prose of the delicacy of another age in English writing while being clear and limpid. It shares complex effects of fear born out of feared possibilities, of violent appropriation, of which no woman is free in a male-dominated society. And this prose style delights throughout the reading experience, injecting complexity into apparently simple storytelling. In such apparent simplicity complexities can lie in simple references to the mythical world and I think this is so in the attitude to the pale narcissus, vulnerable to be plucked. For me this stands in beautiful harmony with the retelling of the story of Narcissus in the Philomela section, in which stories of vulnerability to male cruelty include this one of a male vulnerable to his own self; ‘A creamy-golden, delicately scented flower …: a narcissus’.[11] There are other stories which show males vulnerable to the harm the possessive attitude of male dominance ensures: for instance in retelling the story of Ganymede the pain felt by the visceral piercing of his skin by the talons of the eagle that Zeus becomes to rape him is emphasised and the cruelty of ‘sport’s’ dependence on assertion of species dominance made a feature: ‘… Ganymede cried out in pain and shock as claws gouged his flesh. He was caught aloft like a fish on a hook’.[12]

There is nothing strident about the sexual politics here, just a firm stand against the injustice that is the product of rigidities built into ideologies of male power and patriarchy, often in the name of the Gods, and infecting even female Gods, whose stupid cruelty is oten emphasised to, just as Penelope can find it in her to find Athena wanting in some quality we call, wrongly of course, femininity. This attitude to sex/gender as complexly constitutive is symbolised in the Creation myths in the Athena section and the role of males in placing their right to powerful dominance over love and loyalty. The need for something other than masculinity represented by power and even cold-blooded justice is represented in Prometheus by Higgins, who talks to humans ‘very quietly, very slowly, … hoping they would respond to his gentleness, if not to the meaning of his words’.[13] Pandora, in Higgins version of her, sees, like Miranda in The Tempest how ‘beautiful men are’: ‘What a brave new world’.[14] Pandora and the creation of women in the world is really the birth of a principle of interactions of sex/gender and the release of men from a model of masculinity entirely locked in power and control:

With the arrival of women, the men ceased to be like children, innocent and ignorant. They began to know love. And joy, and the pain of loss, the ache of desire (often for each other): they became, in fact, fully human, …’.[15]

It should not go unnoticed that The arrival of women is as much the advent also of queer sexualities – of the boundary-crossing that love and humanity entails in place of rigid patriarchal law. In her ‘Notes’, Higgins is clear is that she is, without apology, correcting the poet Hesiod, from which the story, told twice in his Theogony and once in his Works and Days, comes, and wherein:

… his Pandora is accursed, opening her clay jar (a not very occluded metaphor for her vagina) to bring misfortune to men. Hesiod, in general, is baldly misogynistic in a way Homer, say, is not … I have taken the liberty of switching the story around, using her name – meaning ‘she who gives all’ – to suggest that she in fact allows men to discover their true humanity in all its moral complexity.[16]

Here we have it. A compiler of stories is also she who takes ‘the liberty of switching the story’ when necessary to make them meaningful to us in a way that is not stained by their continual use in a patriarchal cultures since that age ‘to offer models of male virtue for their young readers’, from which women were ‘relegated to the background’ and queer ‘desire was usually banished altogether’.[17] A minor example of such assistance given to the story to make points about the oppression of both women and that wrongly labelled ‘feminine’ (qualities of passivity and acceptance for instance) is the way in which, in the quotation I cite in my title, of Higgins making it clearer than ancient authors do that male stories about women often edit out information (using an ‘economy with the truth’) about the wrongdoings of men – and the perfidy of some of the most time-serving of masculine values.[18]

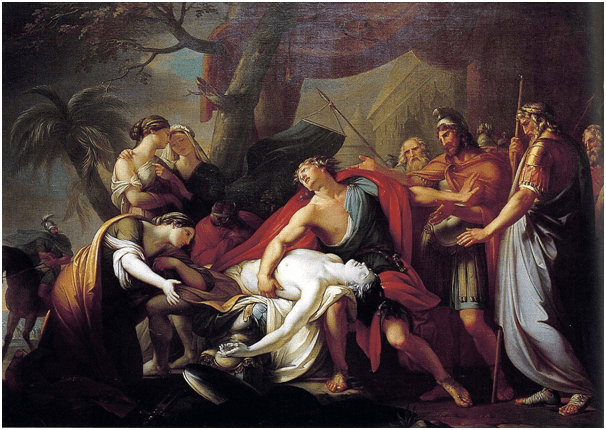

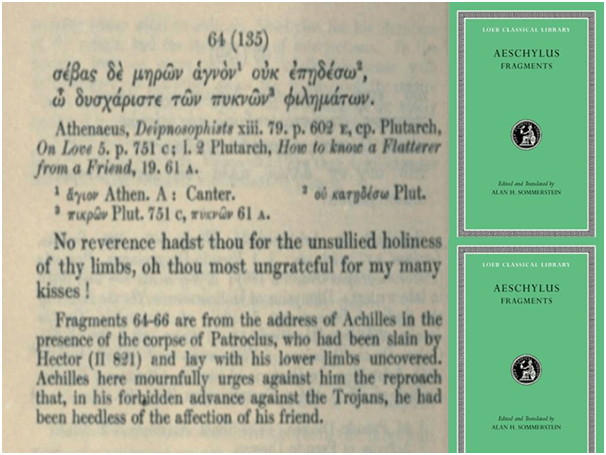

And Higgins marks this by her reinvention particularly of Penelope as a figure of strong female coping within a patriarchal culture, who is in fact less normative, orthodox or gullible than men like Hesiod might be imagined to be by her. She becomes a figure that questions ideologies by questioning the existence of anything but the effect of mundane complexity in a real world where the sky is ‘below us in some way, as well as above us’; a world where norms are disrupted by realities.[19] If she can invent ‘Penelope’s scepticism’, this author still looks for models for such invention amongst marginalised traditions or artists who use such traditions. Let’s take two examples before ending. First the treatment in the ‘Helen’ section, of the story of Achilles and Patroclus. Higgins is a good enough classicist to let his Helen know that Euripides (taking his story possibly from Stesichorus) imagined the body that represented her in Troy was ‘a phantom made by the gods’ rather than a real and beneficent, not malevolent as some male Greeks would have her, being.[20] But she also can use a minor fragments of verse attributed to Aeschylus to ensure a case is made for the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus being a sexual one: ‘the surviving fragments of Aeschylus play Myrmidons are explicit, with Achilles, heartbroken, recalling sex with his lost companion’.[21]

I love this reading, of course, although as the English translation in the Loeb Library version with an emphasis here and elsewhere on the chaste (the translator’s word in another fragment) shows, some classicists might strain at saying just how sexual and visceral is the body contact referred to, with its reference to ‘unsullied holiness’.

Other translations of course might afford more free interpretation of whether the kisses Achilles gave to Patroclus were as unsullied as this literal translation makes them. Here, for instance, is Anthony Stevens rather freer translation of the same fragment made for his dramatic reconstruction of the play in 2011: ‘[ACHILLES: (To Patroclus) Ungrateful for my lavished kisses! Your own pure perfect limbs you took for granted!’[22]The emphasis on the ‘perfection’ of the body of Patroclus allows less room for the Platonic ideal that may be indicated in the more literal Loeb translation. Yet we ought to treat this treatment of authority by Higgins with the same allowance for liberty. The aim is to foreground queer desire. It shows the crafty weaving done with the use of sources and invented material.

This is true even more in the use of wide reference and complex woven forms of authority from different arts and discourses that Higgins associates (again using a weaving metaphor) with Ovid’s ‘fine-spun song’ and Homer’s ‘shrewd design of the Odyssey itself’, which she also associates with Odysseus’ own cunning: “I wove all kinds of wiles and cunning schemes”.[23] That Higgins shows that writerly wisdom is a kind of cunning tells us more about the role of fictional retelling: it often has a purpose or ulterior motive, as does Ulysses-Odysseus, that it hides. And that is why ‘weaving’ is important here – it a means of lauding the function of fiction as purposive discourse akin to lies as much as telling truths, if for a supposed higher purpose. Hence the purpose of making the central storyteller of the story neither an aristocrat engaging in a pastime nor a Goddess using weaving to assert control of the bigger picture but a commercial weaver famed, like a good storyteller like Homer, for her ‘design and invention’: Arachne.

The emphasis on class as well as species difference between Athena and Arachne in this story surely owes a great deal to Velasquez’s fabulous painting Las Hilderas.The painting creates a hierarchy of class emphasising luxury, power, light but also armed threat dressed in male garb against the hubris of the assured female craftsperson (at least hubris if you need those skilled only in technique to know their place). In fat Arachne’s self-pride is hard won and her complaints against Athena, not unlike those we shall see Penelope make, though Penelope has more social power than Arachne.

And Penelope’s story will end with a cunning reminder that the lowly can win if they are patient. When Penelope finishes ‘undoing the work’ she has already woven, she abandons weaving to an apparent vacancy. But there is no vacancy for even when the palace roof later collapses there is hardly noticed, and hiding its power under a cunning guise of insignificance, labour continuing: ‘… it was only spiders who still wove there. They caught up the flies in their glistening threads, and their strong webs did not break’.[24]

For there is another authority here behind the story of Arachne as consummate and strong female artist, that, in the Notes, Higgins mentions only as an aside in relation to its use of a motif of making, destroying and then remaking the artefact, pioneered one might say by Penelope, in Louise Bourgeois and her fascination with spiders (see my blog of a recent exhibition at this link).Higgins says in the Notes:

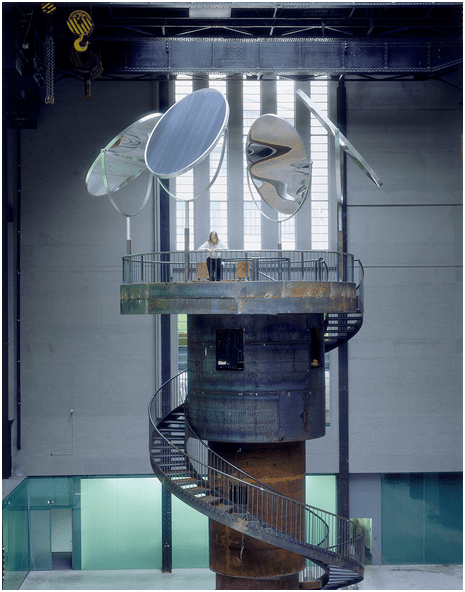

I do, I undo, I redo is the name of a series of tower-like sculptures that the artist Louise Bourgeois (the daughter of tapestry restorers) made for the Tate Modern, London, in 2000.[25]

There is an example below of one of those towers.

However, the spider has been in Bourgeois’ work an image of the constructor and survivor over her career, most notably in her Maman sculptures. Higgins goes to great lengths to show the injustice of Athena – her laws and her art make her victory in any contest inevitable because they are designed with that end, and that end only in view: ‘My tapestry isn’t about human wickedness. It’s about how no one, not even Poseidon himself, can beat me in any contest’.[26]

This is a beautifully made book with even more beautiful illustrations by Chris Ofili. For that reason, you should buy it in the sturdy hardback, but even without that exterior beauty, it is a wise and a strong book, that adds to the wonderful debut book of Higgins’ on the theme of the web as a metaphor of art and woman’s survival in her earlier book, of which I said in my blog on Red Thread: On Mazes & Labyrinths (follow link to see blog):

There is some suspicion of such approaches from some older art-historical traditions, such as Panofsky’s supposedly scientific iconological methodologies. Such approaches, based on a fear of subjective interpretation, create paradigmatic stages of interpretative procedure to keep subjectivity in check. Art history, even where it is not based on iconographical reading, has still maintained this distrust of the subjective of which strict ‘period eye’ approaches are the most typical. These insist that that there is a small range of meanings in any one period for any one trope – and hence reserve interpretation for academic elites.

Not so Charlotte Higgins, who allows meanings to cross periods – to change, mutate but also co-exist as in some trans-historical palimpsest. Moreover, these readings allow ‘moderns’ to see ancient art through their own eyes such that whatever a trope means will be layered by history diachronically and networked synchronically and diachronically to associate meanings and even the domain of other tropes – for instance the relation of labyrinths to tropes such as webs, weaving and woods. Her most fascinating reading ties Freud’s love of Michelangelo’s Moses to the riddle involved in how knots appear in Moses’ beard as a reflex of emotion, thought and the birth of psychological machinery for evaluation (56ff.)

And Higgins is right that there is something special about the retellings of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Roger Lancelyn Green and Robert Graves but that, in the end, the life of such stories is not timeless but ‘timely’. If she excepts from this view somewhat Ovid‘s Metamorphoses, it is because that work in form and content is not only about time but dramatises its variability: ‘Nothing is stable, it says. Everything is contingent; matter is always on the move’.[27]

All the best

Steve

[1] Higgins (2021: 300). From ‘Notes’ pp. 270-300.

[2] Ibid: 294. From ‘Notes’ pp. 270-300.

[3] Peter Stothard (2021) ‘Picking Up the threads: Highlighting the heroines of Greek myth (Review)’ in the Times Literary Supplement (October 22, 2021).

[4] Ibid: 273 & 296 respectively.

[5] Ibid: 294.

[6] Ibid: 277.

[7] Ibid: 269.

[8] Ibid: 214.

[9] Ibid: 213.

[10] Ibid: 33.

[11] Ibid: 91.

[12] Ibid: 132

[13] Ibid: 29.

[14] ‘How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world /That has such people in’t!’ (see Brave new world Shakespeare Quotes – eNotes.com) is reflected in Higgins language for Pandora, in Higgins (2021) op.cit.: 30

[15] Ibid: 31

[16] Ibid: 271f.

[17] ibid: 7, From ‘Introduction’ pp.1 – 16.

[18] Ibid: 300

[19] Ibid: 269.

[20] Ibid: 268

[21] Ibid: 288f.

[22]Anthony Stevens (2011: 13) TRILOGY: three lost tragedies A pdf available at: trilogy.pdf (wordpress.com)

[23] Ibid: 13 in ‘Introduction’

[24] Ibid: 269

[25] Ibid: 298

[26] Ibid: 144.

[27] Ibid: 8. ‘Introduction’.