From a rebellious Northern Powerhouse to a pillar of the establishment – the echoes from Raby’s rich past. This is a blog on a trip to Raby Castle on Sunday 31st October 2021 (Halloween) provided for my husband Geoff and me for my 67th birthday (which was actually last week 24th October) by wonderful friend, Catherine. [For the e website to the castle and information on visiting, follow link: Raby Castle County Durham | One of England’s Finest Medieval Castles]. Written with the aid of the new house guidebook.

Sometimes days change the face they wear, their beauty and joy revealing itself the more you lose your own gnawing care for an increasingly gloomy self, the more you accustom yourself to them, like some friends. This day was like that and was a gift, from a friend who fits that description too, for my 67th birthday. Reaching 67 felt a gloomy cognition in itself when I woke, even though my actual birth date was a week ago. On top of this the day looked unpromising that morning with dark cloud cover and a show of the very hardest rain cascading on us as if to make the point that this the worst weather as yet this winter. Even our dog Daisy (the grounds of Raby Caste are dogs-on-leads friendly (even the superb café) seemed unwilling to face the rain (such is the Staffie nature) and pulled back to return to her nest in the car boot. It poured as we investigated the walled gardens – beautiful though they were, adding gloom aplenty to the look of the imprisoning yew hedge – topiary fashioned to look like waves of lava about to submerge you (the metaphor is from a good friend Justin who saw the photo on Twitter when I posted it. It was hard to smile and show how truly grateful I was in the circumstances to dear friend Catherine. But there was fun, beauty and after a wonderful tour of the Castle interior the sun emerged in time for the Castle, day and far away deer to look entirely different. By this time i had exhausted the battery on my phone so I asked Catherine to take the pictures that show the contrast in light and clemency of weather before and after that tour. Here is the contrast:

You possibly get a better idea of the day of the morning gloom from the collage of pictures of the lawn hedged by the unctuous waves of monstrous yews. Easy to recite that morning Tennyson’s ‘Dark yew which graspest at the stones’, in full conscious that Tennyson was aware of the sound similarity between ‘dark yew’ and ‘DARK YOU’ (I too can be a morbid creature like the depressive, and oft suicidal, poet himself was) ‘darkening the dark graves of men’.[1]

But mood often takes the colour of association – even in the language we use to describe for instance ‘gloomy weather’ and even Tennyson, when he repeats the line in In Memoriam’s lyric 39 which I have already cited we should have remembered that the Dark Yew (You) has already been identified in Lyric 2 (with near the same words in the line otherwise) as an ‘Old Yew’ (You). We all get it eventually when we re-read that wonderful poem. The Old You (yew) of the opening of the poem (Lyric 2 as I said) needs only to identify that it is a ‘dark’ you (in lyric 39) before seeing the promise of new growth and a lighter more hopeful new You (yew) in prospect. This newer you no longer thinks mournful melancholia to be the only possible response available to living people when they remember something or someone lost: ‘Old Yew, which graspest at the stones / That name the under-lying dead, …/ Thy roots are wrapt about the bones’.[2]

There is wisdom in Tennyson that applies to more than the loss of his dearest friend, the ostensible subject of the long poem I am citing, loss is the mode of depression – even the loss of silly desires to have a ‘good day’, or of one’s youthful hope and a whole range of other minor prompts to optimism rather than pessimism. I loved the Castle tour. It was like the reviving weather, sign of the sun and long glances at the deer in Raby’s Deer Park that gave instances enough of what I have called above, ‘minor prompts to optimism rather than pessimism’. With returned gratitude to Catherine for giving us old men this good day out one remembers what a good friend she is, as is her husband Paul (as bright and intelligent a man as she a woman), who I once (in the distant past) taught at university. Nice memories – reviving a ‘new you’, even if of a more trivial kind than that evoked by sombre-faced Tennyson.

Arriving at Raby in the torrents of rain, we were parked neatly into a puddle and asked whether we were here for the Halloween Trail. This possibly added to the grim prospect at the time but all I remember now is that the wicker Halloween fantasy figures actually already began to delight me – I am still a child inside as loving friends know – whether because of the faux ridiculousness of the fear they were meant to provoke (the spider babes fleeing the web on one lawn) or the airy lightness of the winged ‘fairy’ unicorns. It’s worth a collage of the wet visions. They might delight you as they did me:

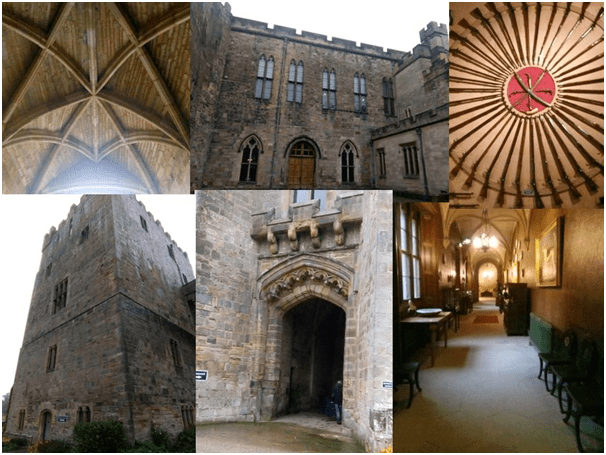

But the best was yet to come. It was still raining heavily as we passed Clifford’s Tower, with some original slit windows from the Neville ownership of the old castle in the reign of Edward III (1312 – 1377) in the fourteenth century but the start of the enchantment of a castle trip is really gauged by entering the inner courtyard (below the keep tower) at the original sole entrance in the days where fortification mean real defence in a borders land of the Neville Gateway.[3] I began to doubt myself because these excited me and, truth to tell, I am not a person who usually favours medieval architecture or culture.

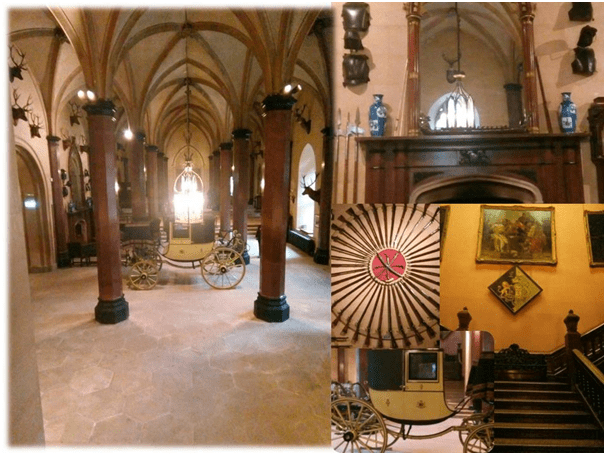

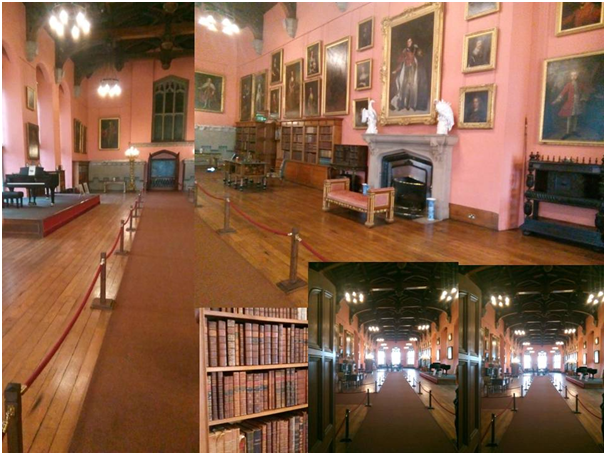

I sometimes wonder anyway whether my tastes aren’t rather Victorian mock-Gothic rather than Gothic (especially in secular architecture) – formed rather by Victorian civic and public architecture with its anachronistic mix of ‘styles’ rather than by Ruskin – although there is much about Raby that released the mock-gothic taste from the eighteenth century onwards. It is a taste that sprang into exotic form of eighteenth-century-orientalism as you see in the room now known as ‘The Library’. From the entrance in, the castle interior delights in its anachronisms where the genuine medieval elements are fused with differing appearances that taste in the gothic. These first began to attract in the eighteenth century, if we except English Renaissance Arthurian fantasies like those that speak through Spenser’s The Faerie Queene. And although major rebuilding stopped at Raby as early as 1891 under the 9th Lord Barnard,[4] continual sympathetic and possibly unsympathetic (depending on your point of view and / or historical and taste preferences) ‘restoration’ of interior decoration continued to be applied. The small lobby you first enter from the medieval passageway with its view down a corridor to the display of a circle of inward pointing artillery in a star fashion around a centre of crossed military swords and pistols confuses your historical sense. There is much of the mid twentieth century in this small room that seems to be dominated by the 11th Lord Bernard (1923 – 2016) and his portrait. And there is often much more of game hunting than military prowess in the overt display of killing machines.

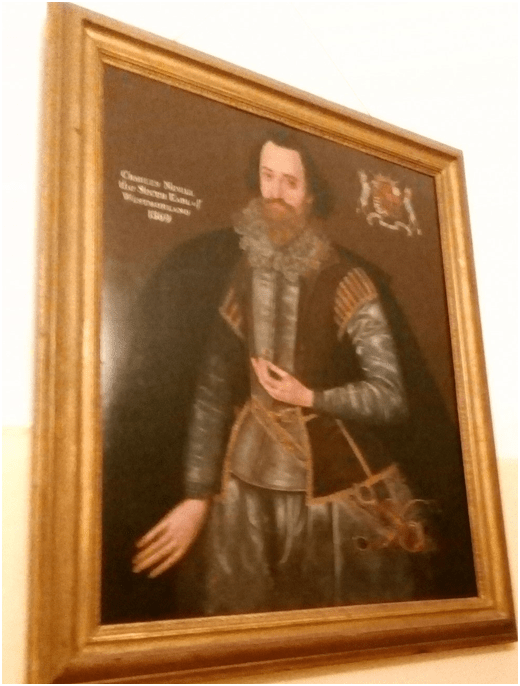

The Nevills, for whom the medieval gateway is named, hardly get a look in the house other than in a portrait that appears before going on the tour of the rooms proper, but this rebel Catholic lord intrigued me throughout, even though having lost the estate following involvement in the 1569 Northern rebellion, it went to another party (Sir Henry Vane the Elder) altogether in 1626 – the Vanes were more allied to Parliament than monarch, Sir Henry Vane the Younger being executed by Charles II in 1662. But this turbulent history of civil and religious strife is not in the tone of Raby now and we have to imagine it even looking at the portrait of Charles Nevill, the last Earl of Westmoreland.

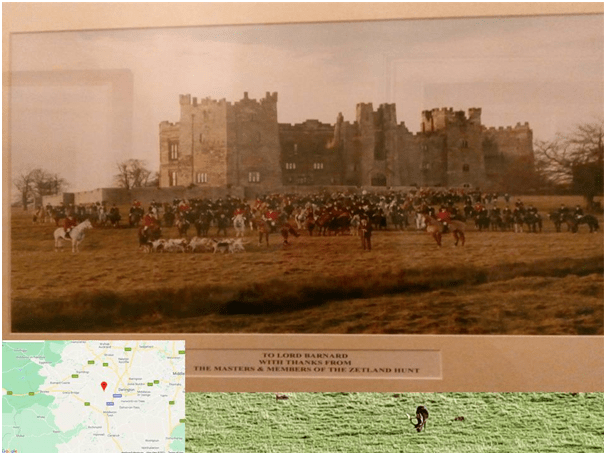

We will see this reduced to the domesticated (for aristocrats at least) pursuit of ‘the hunt’ in later years and though my collage below hints at stags – those living in the Deer park currently – the hunt largely meant foxes. In the ‘small drawing room’, which the guide in the room (and the guidebook) assert to be very ‘masculine’ this interest is shown in various ‘sporting and equestrian pictures’ including one recently acquired (I believe) by Sir Alfred Munnings painting of the Master of the Zetland Hunt, Herbert Straker, who is the guidebook informs us, over its reproduction of the painting, ‘the present Lord Barnard’s maternal great-grandfather’.[5] Another evidence of this I noted is a much lesser painting presented by the gentlemen of the Zetland Hunt (which still exists) to the now late 11th Lord Bernard. I find it indicative of the other very interesting paintings of the association of the Hunt to Raby which Raby in the Regency period bruited as the trademark of its men.

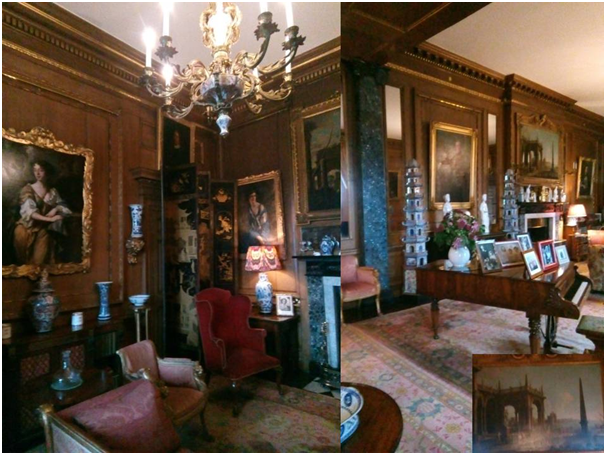

The small drawing room otherwise is difficult to describe by standards other than the aristocratic class of the Regency as masculine, except that it provided a retreat from the world dominated by what was supposed to be the flamboyantly decorated taste of women in the Large Drawing room, of which more later. But hunting pictures and drinks table aside, this room mainly speaks of money than testosterone – feeling a little like Dickens description of the Veneerings in its chandelier, mirrors and other reflective but ornate surfaces where even the clock is a miniaturised Baroque fantasy. Otherwise it is a very domestic interior intended to glow rather than reflect sombrely.

Rooms of course can easily be renamed we should take with a pinch of salt the next large elegant Library room where there are books but not here dominant, not so much as in the Ante-Library annexe to follow. Rather this room is a kind of song of praise of the eighteenth century cosmopolitan taste of the aristocracy, extending from elements speaking of the Grand Tour, with its emphasis on a capriccio of anachronistic European historical artefacts and architecture that here get mixed with a Orientalism and displayed in some fine items we ought to call Chinoiserie, such as the in the George I chest that stands between two ornate pagodas and on which chest sit tow figures of the Chinese Goddess of Mercy.[6] This taste is itself an extension of European interests and Rococo decoration seen by English gentlemen in France and Germany, even though some Cantonese items are also here. It speaks to us of the excessive contradictions of the British trading imperialism that produced the shameful episode in British history we call the Opium Wars.

Collection of exotica such as that was as much a feature of Grand Tourism as those medleys in the pictures on the walls, including two favourites of my own, which show fantastically-assembled mixes of anachronistic architectures. A lovely Marco and Sebastiano Ricci Ruins of a Classical Temple is in the guidebook (a small portion shows on the right of the first of the collaged pictures below) but I loved others. One is less aesthetically good, and i forget the details given to me by the guide, although the date 1741 sticks, of a temple and one of the many obelisks (‘needles’) imported from the East by Napoleon to Europe and freely used by English gentlemen at home. My photograph of it was so poor I merely inset a thumbnail in the collage below. I think however the historical and geographical muddles it demonstrates (much to the taste of capriccio loving aesthetes) is clear enough however.

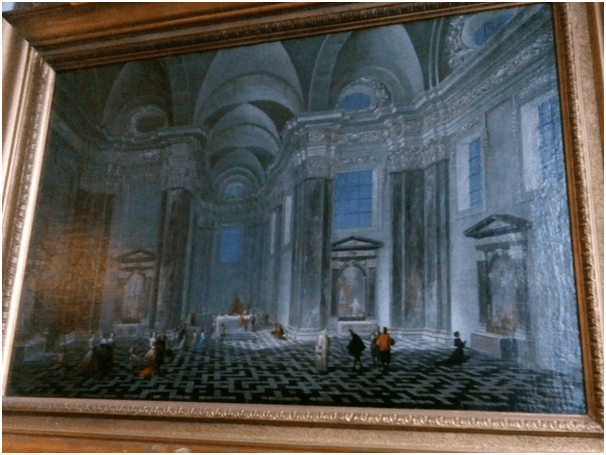

I would say the other painting is a greater favourite although its painter is unknown. It fascinated me as an example of how this by now Establishment family, were living in the home of an earlier noble family (the Nevills) whose estate was taken by the Elizabethan Crown. This was because, as already said, of their involvement in the Northern Uprising of 1569 in favour of the Catholic claimant to Elizabeth I’s throne, Mary Queen of Scots (the Nevills had been prominent under Queen Mary Tudor). The Vane family, who bought the estate from the Crown had their fates mixed again with the Neville family tree in the late nineteenth century, and although English Protestants, this painting shows an almost sentimental interest in Roman Catholic observance. I do not know where to go with the reflections this raised but it kept me gazing at this beautiful painting in which holy architecture dwarfs human observances, which try to expand into that space. Probably all of reflections as I stood before this lovely painting are subjective moonshine rather than thought but they entranced me for a while. Look at my poor photograph of the painting anyway. It may entrance you, even if only as a set of ideas about humanity, belief, art and space.

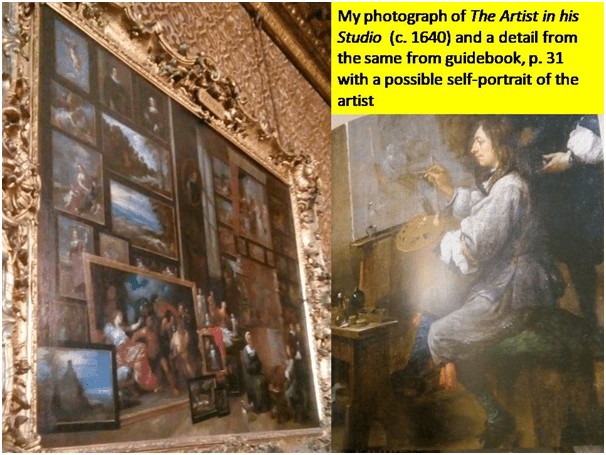

I think my liking for this tour increased from this point. Moving to the Ante-Library there were not only more books to see but some amazing Flemish paintings and especially some wonderful examples from David Teniers the Younger. Those Teniers entranced me yet again, especially one including the artist’s self-portrait dwarfed by his studio and a collection of paintings that crowds out all other space across the height and width around him, and possibly even the capture of time in the painting. This painting is so unlike others of Teniers in the Ante-Library (and ones I have seen before see my blog from this link). What dwarfs the artist in the painting is an entire tradition of the making of visual imagery, however eclectic in its appearance. I believe the existence of this painting is why I could buy the lovely book in the bookshop that appears in a picture above.[7] Again I can do little more than let you see my poor photograph of that wonder.

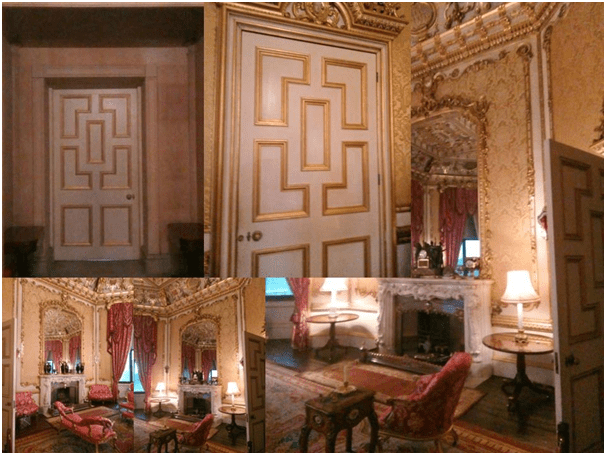

The Ante-Library leads to the Octagon Drawing Room. This room is an impressive space where opulence is at a maximum. What grabbed me though is its place in the architecture of the building. Although a kind of social recess, its rationale is a large gilded door leading to the Entrance Hall, busy on social occurrences with the arrival, after 1848 at least and the William Burn alterations including this room, of carriages containing the fashionable. On leaving they would leave via this door straight to these carriages. On arrival we would move from the baronial feel of the Entrance Hall to this opulent feast on the eyes. Here is my collage containing shots of both sides of that door and the view of the gilded pink confection, endlessly reflected in its mirrors on each side intended to impress even the most jaded bourgeois or aristocratic entrant. It is the world of Veneerings again, where baroque fantasies live on roof and walls. In retrospect I feel less amazed than fooled by this world, especially when one remembers that it was designed in 1848, the year of European Revolutions.

As you rub your eyes you can enter the Victorian Dining Room with a more subdued opulence. The art here seems there to add to the opulence, and the inability to get near it is a pity since the Luca Giordano there showing the heroic sacrifice of Marcus Curtius, although it’s difficult to reconcile the story of the pride of a republican citizen (as in the story below told by Senior Guide, Keith Simpson) with the opulence of the setting otherwise:

The seers of Rome said it would never close unless Rome’s most precious thing was thrown into it. Marcus Curtius put on his armour, mounted his horse, drew his sword and declared “Rome can have no more precious thing than a brave citizen!” He then rode his horse into the abyss. The chasm closed, and Rome was saved. Hurrah![8]

The baronial and mock medieval Entrance Hall which follows feels like a movement from elegance to a sentimental view of history, with its mock-medieval fireplaces, even a stuffed fox to replace that once made a pet by earlier family members and the fine carriage standing on the purpose built carriageway. Here we stopped to watch a 20 minute film well worth the wait, which explained some things we had seen and things we were going to see.

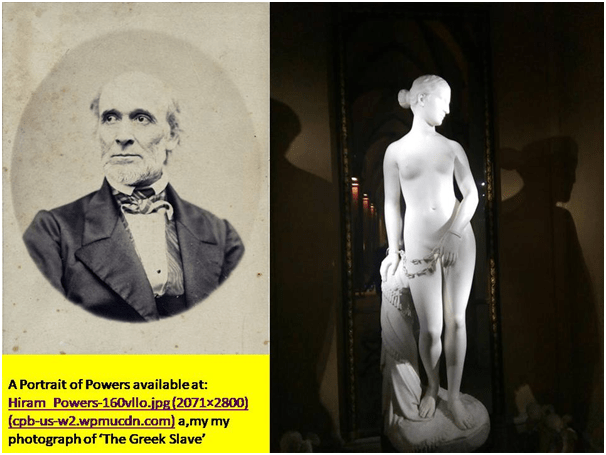

As we passed the grand entrance (already shown above) to the Octagonal Drawing Room, you see the Hiram Powers ‘The Greek Slave’ which had appeared at the 1851 great Exhibition, suitably covered so as not to alarm Queen Victoria and publicly bruited by Elizabeth Barrett Browning as an icon against slavery and ‘serfdom’ of other kinds:

… as if the artist meant her

(…)To so confront man’s crimes in different lands

With man’s ideal sense. Pierce to the centre,

Art’s fiery finger! and break up ere long

The serfdom of this world.[9]

This is a tremendous room. It is beautiful even in its anachronisms, artifice and sentimentality. Of which more though again on a sound medieval architectural base in the ‘Baronial Hall’ upstairs where it is rumoured 700 knights plotted the 1569 Northern Uprising against Elizabeth I. Now it seems a place for show, as it must have been through the eighteenth and nineteenth century. It is too large to photograph well.

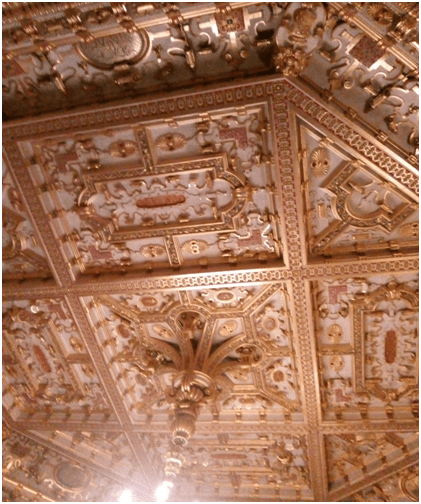

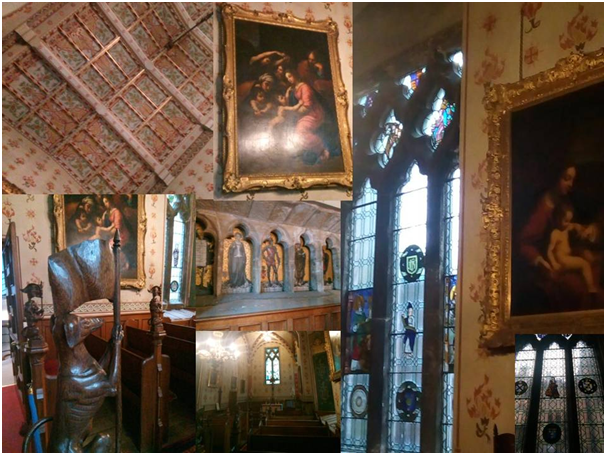

We descend to the Chapel, which, we are told was once visible from the Great Hall above when observances were a great deal more regulated. It again strikes with the beauty of its records of Christianity – some more in the spirit of the Grand Tour as in paintings from the ‘school of Raphael’ and a beauty (once thought a Murillo) of the Spanish School. Even more inexplicable are fragments of the most beautiful stained glass from the venerable and ancient St.. Denys near Paris, wherein high Gothic Catholicism meets mock gothic cleverly painted (after tomb original effigies but added in 1901) in the old stone panels at the end of the nave facing the altar.[10] The roof stuns of course.

From there ‘UPSTAIRS’ gives way to less grand stairways used but the servants of the castle – to a medieval kitchen, with its original mid-placed fluted vent to allow escape of heat from the kitchen but considerably prettified now. Then to The Servants Hall (I have omitted the bedrooms from my tour). Along way are windows showing the anachronisms of the exteriors facias where medieval and modern drainage systems are seen, passage ways and stairways. These will all be represented in a medley of collages of my photographs below.

And thence to lunch again in the Courtyard Stables: I recommend the frittata. And my camera-phone exhausted of energy, just more memorials of those outdoors when the ground was sodden and the skies grey. But in memory now, it isn’t so bad you know.

This is a rambling subjective piece but I did it to show my joy at the trip for Catherine. But I think it shows that Raby is worth an excursion – more than I even suggest here.

All the best

Steve

[1] Citing Lyric XXXIX of In Memoriam by Alfred Lord Tennyson. Available at: In Memoriam A. H. H. OBIIT MDCCCXXXIII: 39 by… | Poetry Foundation

[2] Citing Lyric II of In Memoriam by Alfred Lord Tennyson. Available at: SI (victorianweb.org)

[3] Guidebook (2021: 13)

[4] Ibid: 9

[5] Ibid: 19 for reproduction and text cited here.

[6] Ibid: 21

[7] Roland Recht, Catheline Périer-d’Ieteren, and Pascal Griener (Foreword by Peter Burke) [2007] The Great Workshop: Pathways of Art in Europe 5th – 18th Centuries europalia.europa Festival in Brussels, Europalia International, Brussels / Mercatorfonds, Brussels.

[8] Keith Simpson cited in Favourite Things: Grand Painting with a Modern Message – Raby Estates

[9] Cited: “The Greek Slave” by Hiram Powers (1805-1873) (victorianweb.org)

[10] Guidebook: 57