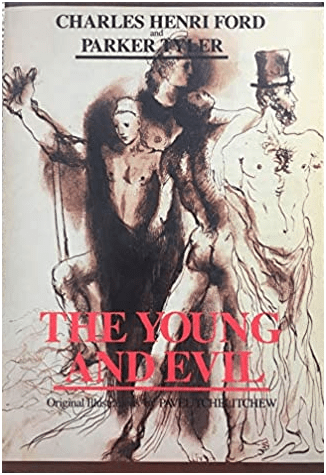

‘The world calls ‘evil’, and has always called so, whoever rejects labels and methods and systems, even nominal rights and privileges, in order to create its own individual good’.[1] This is a blog reflecting on the achievement of a queer modern idiom and ethic on the meaning of ‘love’ in Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler’s (1988 reprint of the 1933 book) ‘The Young and Evil’ [Illustrated by Pavel Tchelitchew] A Seahorse Book, Gay Presses of New York.

It is sometimes said that The Young and Evil was the first ever queer novel but this is said about so many books and there are too many candidates for a category that itself celebrates diversity of sexual being outside the pressure of hegemonic norms, so I don’t intend to even have an opinion on this question. After all, if it matters at all, it matters as a novel that speaks to traditions in the development of twentieth-century art that never reached the mainstream or have slipped from being considered part of that mainstream. In many ways this novel is necessary to place in a tradition of other queer writers once more celebrated and once considered major such as Gertrude Stein and Djuna Barnes. It is a novel that needs you to confront the surrealist ambition of its prose style as Stein does, one that bows to the simplicity of declarative sentences such as that style admired in Hemingway by Stein but disturbs or queers it so that we feel destabilised in the search of either a unitary meaning to what we are reading or a direct window onto what appears on the surface to be the real world. It is a prose style that finds a greater reality in the strange links, sometimes into a reality that is entirely numinous and indescribable except by abstraction, and connections between things of which its sentences demand you become aware. It has learned of course from the methods of James Joyce and, to a lesser extent, Virginia Woolf but Ford may also have thought of David Gascoyne. This is the case in this favoured sentence of mine describing the surplus of available male sexual activity that Julian is distancing himself from at the moment as he leaves a favoured place for picking up young men:

The push flesh into eternity and sidestep automobiles. I bemoan them most under sheets at night when their eyes rimmed with masculinity see nothing and their lymphlips are smothered by the irondomed sky.[2]

The novel sometimes identifies this ‘associativeness’ (if I may call it that) with ‘poetry’, but there is more to the prose than its poetry: there is the assertion of a kind of literalness that insists on working out all the meanings implied by the silences in a more selective and edited choice of words. Take this sentence from Chapter 5, ‘The Party’: ‘The next night Julian was expecting people he knew and people he did not know’. Logically this sentence ought perhaps to have ended before the ‘and’, since to talk of ‘expecting people he knew’ presupposes, since expectations imply their surprising non-fulfilment; that he is going to be confronted with ‘people he did not know’ whatever the force of those expectations. To add then ‘and people he did not know’ makes us think again about the surplus meaning meanings sometimes attached to a verb like ‘expected’, describing a mental event in which suspense and non-fulfilment hangs at readiness, of which we are usually unconscious. This is typical of modernist prose in say, James Joyce, and certainly in Gertrude Stein.

I start here to warn readers that it is the characteristic of this book as a means of linking a queering of the terrain of sexual and other relationships found in heteronormative novels is linked to the project which in the writing of that period brings about an innovative modernist prose style that tries to show that truth about the world can only be conveyed by a more scrupulous attention to language. Only under this condition can it be used to describe it in a way that reveals that the world itself is much queerer than we like, in our terribly lazy way, to think we know, if we subscribe to normative expectations.

My own feeling is that this novel has a rather soft heart and attempts to redefine the novel of romantic love by queering the terms used in such novels, and that of ‘love’ in particular. To my mind the narrative of the novel turns on the very moment at which Julian feels ‘an absence of something he had held dear a few minutes before’.[3] For in this novel things that are considered normative assumptions of relationships between persons, like the availability of love, emotional value (what is ‘dear’), care and support, cannot be presumed to either exist or be knowable even if they do.

Karel remembers, while sleeping asexually in the same bed (and same pair of pyjamas) with Julian (based, as I have said, on Ford) for the first time has a dream-like memory of what caring is like for a child on his fifth birthday party – it is a thing, if it is even that, tied to immediate pleasure only and which passes with it. Surveying his guests as they arrive he feels precisely this fugitive caring, gone before it is registered, like the ice cream which is its equivalent. Underneath ‘care’ that flies is a more substantive fear that the feeling of being protected and that protection and care exist for one are an illusion almost fantastical as an ‘elephantine globularosity’, whatever that is. It seems to be symbolised that caring in a doll he is gifted with, despite the fact that he knows it is considered a gender-inappropriate, and which someone ‘snatched SNATCHED it back to some sort of heaven I suppose but my heart.’[4]

The deformations in this sentence – the emphasis given to the repeated act of violent denial (in ‘snatched’) and the unfinished phrase at the end which makes a ‘heart’ as vacant as the ‘heaven that ‘is it Grandmother is it Mother’ takes that doll from. See how throw away too, like hearts, is caring in the sentence (and how infected by violent purposeless action, power over others and under laid by fear) to which I have already referred in its own unsteady syntax. As you read see too how the excursion to a memory of a fearful past subsists, as if time itself (‘between this and that’) were unstable:

I tear grass from the roots on my fifth birthday lawn and they imitate me the other children and I am glad. And they. Are. Between this and that. I am afraid. Even now. Between this and that there might have been: or were: elephantine globularosities protecting their own children like perfect mothers, unaware that a child (I) of five (I) pranced, ran, stumbled, uncared for except in. O elephantine globularosities, who what are you if you are or could be? Between this and that.[5]

For Julian too things like trust, care and love likewise are under laid with fear and trembling that denies its magnitude and perhaps even fails to be raised to a conscious level, so concealed is it under action, object or metaphor that uses either as its vehicle so that it be not recognised: ‘A softness is a weakness and that submitted to always leaves some sort of something if only a small fear. This was something that could be concealed by something else’.[6]

The same terms are confused when Julian ‘dressed himself while thinking about love’, another romantic uncertainty and

He doubted the sincerity of the people he saw living together supposedly in love. He had never known physical and mental love towards a single person. It had always been completely one or the other. … He was unbelieving when he saw lovers who were lovers in the complete sense and who slept night after night in the same bed. He was quite sure their love was a fabrication or a convenience or a recompense and he did not believe in their love as love. There is a poem about that and he opened a book to read it and came to

We shall say, love is no more

Than walking, smiling,

Forcing out “good morning”,

And were it more it were

Fictitiousness and nothing.

…[7]

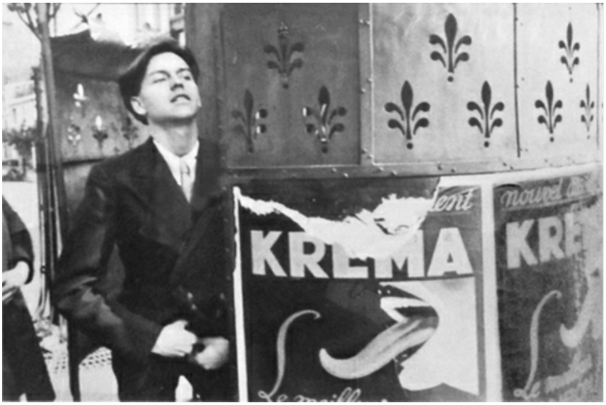

Although taken after the publication of the novel, the Henri Cartier-Bresson photograph above of Charles Henri Ford zipping his fly after a visit to a Paris vespassienne – known for brief sex trysts between men (David Gascoyne, for instance, interrupted a loving meeting with his fiancée to have such a tryst at such a place with Charles Henri Ford)[8] – holds some of the same humour Cartier-Bresson saw in the advertisements of the cat-like male tongue licking the Kréma confection just in front of Ford. Yet there is no doubt I believe that Ford and Tyler were serious in attempting to redefine love and love-story in ways that included multiple attachments, multiple forms of what love meant as an action, cognition or set of embodied responses. Love is not ‘no more’ just because it is the equivalent of the fictitious. Far from it. Fiction in life and art gives it body. Ann Reynolds shows that such moments may represent a continuing debate in modernism between those who clung to romantic (or neoromantic) story and gave it a role in art and attempts by Clement Greenberg to excoriate it:

According to Greenberg, this undermining of illusion, perfected by Cézanne and the cubists and embraced by the contemporary artists he considered most promising, reflected the positivism of the best philosophical and political intelligence of the time, to the extent that “fiction, under which illusionist art can be subsumed, is no longer able to provide the intensest aesthetic experience”.[9]

Watson emphasises that the masking of Ford as Julian and Tyler as Karel was thin and not only for their immediate circle, though their readership would not be large.[10] Both authors claimed to be the main progenitor of the novel but it is clearly about how their complex four-cornered sexual-cum-romantic-cum-money-related relationship is mirrored in the novel, based on Tyler’s diary accounts.[11] It invites even psychoanalysis to the party in which love, sex and other human exchange-interactions become ravelled together, as Julian and Karel discuss their ‘love’ once it is most unevenly balanced and in retreat:

You mean love becomes pitylove and finally pity. I love you.

You don’t know what love is said Karel turning his cheek over. You’ve never wanted me so that every line of me made you ache.

What does my love mean then?

It may be some kind of minor pathology. Whether it is or not i love it.

You love my love for you.

Yes. It is a little curious and a little strange. …[12]

And this conversation goes on tying itself in knots not unlike those seen as problematic by R.D. Laing. What comes out of it is general agreement that only a queer or ‘strange’ definition of love that is the same as that of art to artists matters as something other than what norms otherwise satisfy the world: ‘I feel around me a great coarse essentially foreign world in which only the objets d’art seem friendly, seem able to walk and talk with me’.

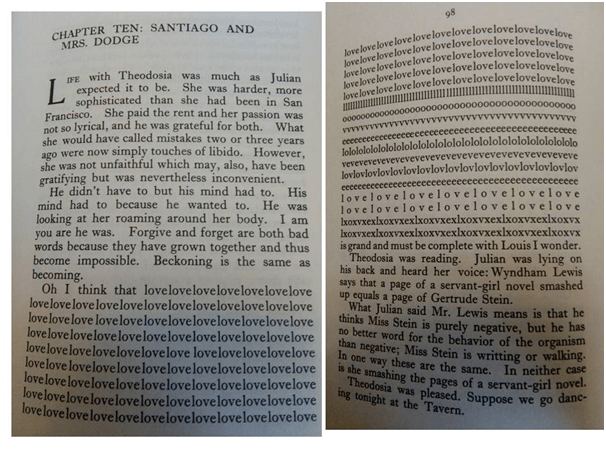

Often the word ‘queer’ is used in exactly a way conducive to supposedly modern uses of it in queer theory where language turns to repetition to suggest it is an iconic poetry: ‘But Karel was thinking of Louis turning queer so beautifully gradually and beautifully like a chameleon like a chameleon beautifully and gradually turning’.[13] This kind of queerness does not confine itself to being an equivalent to be being gay but is a means of re-evaluating life whether or not that includes homosexuality which elsewhere the novel compares to a ‘doll’ (like that received by Karel aged 5 but taken from him). Julian thinks he is a kind of doll when a man in a taxi to whom he somewhat prostitutes himself finds his beauty intoxicating. But what matters is something other than the doll that can also be the doll but isn’t always. It is an attitude to language he and Karel call poetry: ‘A doll does not believe in itself he thought it believes only in its dollness I have the will to doll which is a special way of willing to live my poetry which may be a way of dolling up …’, and so on – the passage is excruciatingly complex syntactically and semantically.[14] It is all a matter of langage – most so when the word love id deconstructed in Chapter 10 for which I need to show you a collage of pages:

So we go back here to what I suggested at the beginning. The queer in this novel is the beauty of its strange/queer sentences and the multiplicity of their suggestions operating simultaneously. It creates a new ethic by spring-cleaning ‘evil’ as a world only the normative word has a use for in a negative way because the ‘good’ of one person is the ‘evil’ of another and neither is right without both making their own good shine through the obscurity of its expression. Watson cites Tyler’s summary that the aim of the book is to show that poetry is that queer kind of life, open attitude to all forms of life and their simultaneous expression. They thought this was happening in modern poetry, which included prose for them, in T.S. Eliot but especially Barnes and Stein, who both appear in the novel.[15] It speaks in Theodosia ‘chanting words like broken musics: I love you’.[16] And in love between boundaries of sex, gender, class and sexual preference for, as Watson also says, there is in this novel no ‘strictly homosexual world, but one of polymorphous sexuality’ (or the polymorphous perversity identified by Freud but badly named for the original and basic infant sexuality.[17] But most importantly Tyler is cited by Watson showing that both authors wanted to emphasise that poetry is ontology not a thin of words alone but of one’s whole being. He even claims that neither what neither he nor Ford realized ‘too consciously was that we were (I hope this isn’t too much of a boast) modern poetry’.[18]

This is a more truly great novel than it is often said to be but was, and is, never likely to be popular, just as a resurgent taste for Gertrude Stein is unlikely, but queer people ought to revere it. I do.

All the best

Steve

[1] Parker Tyler in 1960 cited by Steven Watson, ‘Introduction’ in Charles Henri Ford & Parker Tyler (1988: vii, first published 1933) The Young And Evil A Seahorse Book, Gay Presses of New York

[2] Ford & Tyler op.cit.: 74

[3] Ibid: 71f.

[4] Ibid: 23

[5] Ibid: 22

[6] Ibid: 72

[7] Ibid: 72 – 73

[8] Robert Fraser (2012: 66) Night Thoughts: the Surreal Life of the Poet David Gascoyne Oxford & New York, Oxford University Press

[9] Greenberg, “Abstract Art,” p. 451 cited Ann Reynolds ‘ No Strangers’ Available at: https://art.utexas.edu/sites/files/aah/download-ann-reynolds-4.pdf

[10] Watson, op. cit.: xiii

[11] Ibid: xx, viii respectively.

[12] Ford & Tyler op.cit.: 174f.

[13] Ibid: 144

[14] Ibid: 170

[15] Ibid 18 & 32 respectively, for instance

[16] Ibid: 35

[17] Watson, op.cit.: ix

[18] Tyler cited ibid: xx

One thought on “‘The world calls ‘evil’, and has always called so, whoever rejects labels and methods and systems, even nominal rights and privileges, in order to create its own individual good’.[1] This is a blog reflecting on the achievement of a queer modern idiom and ethic on the meaning of ‘love’ in Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler’s (1988 reprint of the 1933 book) ‘The Young and Evil’.”