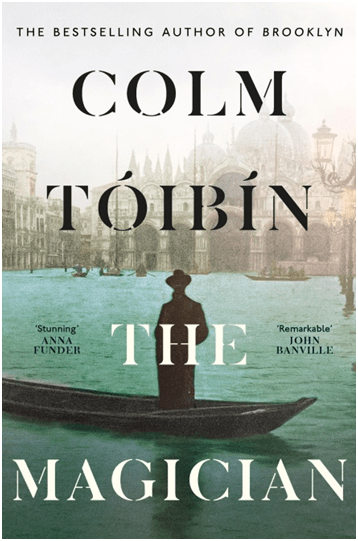

‘The teeming commercial life of the street had its own sensuality. … most people in these streets were men. Thomas derived such pleasure from observing them …/ …. he was like a child surrounded by things he dearly wanted, an almost unimaginable richness of them’.[1] The resurrection of imagined queer lives of famous writers of the long past by queer writers of in the time of the cusp of a supposed modern queer liberation: the lives of Thomas Mann & Henry James in the careful hands of Colm Tóibín. A blog on critical treatment of The Magician (2021) by Colm Tóibín, London, Viking (Penguin Books).

I finished The Magician a week ago and though it is far from my favourite novel by Colm Tóibín, I think it represents an important moment in queer writing where modern novelists who have lived through once unimaginable changes in the legal, social and ethical status of gay men confront the new world, cogniscent that, as yet, there remains no absolute guarantee of that world remaining in the freer and more diversity-respecting form in which it currently is or pretends to be. I enjoyed this book as always with his fiction and admired what I see as clear attempt, at least for those of us who share this common history with Colm Tóibín. But since, though I hope I’m wrong, I do not think that this is the book of his that most deserves to live – the remains for me the wonderful The Blackwater Lightship, not Brooklyn, though I admire the latter too – I have been toying with whether I wanted to blog on it.

I had fully intended to well before I read it following the publication, some weeks before its publication in the UK (and thus precluding comment from most of his British readers, of a review of the novel which infuriated me for the short time one can be ‘infuriated’ (outside of being Orestes himself, as treated by Aeschylus at least) by Michael Hofmann. Hofman is a translator, academic literary critic and writer of poems which the critical review of The British Council say can be an ‘acquired taste’ and which some accuse of ‘prosiness and aposiopesis’, whose main theme seems to be the complicated journey that he has take attitudinally towards his father, a famous novelist in German, Gert Hofmann. Indeed he mentions the latter, somewhat irrelevantly, in his review. Michael’s Wikipedia entry does not mention his poetry, rather dwelling on his literary criticism.

Some academics think it is. / Here is, for instance, Michael Hoffman luxuriating in probably the most damning review of the fictional biographical novel for lacking the ‘reliability’ that comes from ‘original research’ of the academic (that is to say Hoffmann’s) kind. It is as if this scholar of German literature did not realise the fictional autobiography of real historical persons without claim to either quality was a genre practicised by the great German Romantics. He targets his scorn at both Colm Tóibín’s recent (2021) novel of that genre about Thomas Mann, The Magician, and his older work (2004) on Henry James, The Master.

Whilst battling my Aeschylean Furies however, I added a bit to a blog on Louise Bourgeois, relating to the treatment of fictional autobiography or biography, which unfortunately reveals I had not discovered Hofmann’s biography fully. The Furies do make you kind of careless. Lol. Here is the piece in which I discuss, in relation to Jean Frémon’s fictional autobiography of the artist, whether a insight into Bourgeois’ psyche revealed by a possible fictionalised event is ‘dependent on its accuracy to what the Bourgeois family (…) literally said: or in more abstract terms is accuracy to the literal truths of their family life a necessity in exploring artistic personality’:

[START QUOTATION] Both books to me are like biopics, a slightly vulgar, slightly unattributable, cod replaying of celebrated or distinguished lives. Call them bionovs./

…

In all this soap opera, tedious and poorly told and lacking insight and accuracy to them as know, breathless and arbitrary and inconsequential to others, it is hard to see “Thomas”, …[END QUOTATION] [2]

What isn’t difficult to see here is the emboldened class prejudice registered in the wittily ‘undereducated’ cod phrasing of the reference to original researchers and scholars as ‘them as know’ (like a speech from one of Bernard Shaw’s underclass in Pygmalion), the reference to popular genres (biopics and soap operas) and the distaste for vulgarity and for those to whom, they not being identifiable at all since they are not one of ‘them as know’, truth and accuracy are ‘inconsequential’.

It stinks of the academe of the early twentieth century – grossly wallowing in the entitlement of the ‘few’ to insight, truth-telling and sensitivity denied the ‘many’. Now this may be an attack just on Tóibín as a particularly poor writer in Hofmann’s view that does not apply to others, after all he excepts Penelope Fitzgerald and his own father, Gert Hofmann (who died in 1993).[4] But it is difficult to sustain such exceptions from the specific objections that novelists need to invent things that feel different from a biographer’s truth (where the life says hic’ surely even Goethe romancing and pillaging for his own purposes the life of Torquato Tasso is ‘allowed to say hoc’). It feels so pertinent to me that Hofmann illustrates his point about the necessity of a degree of historical accuracy with reference to the grammar of Latin syntax (thus again defending truth from the many with ’small Latin and less Greek’).

I feel less ‘angry’ now than this paragraph is, but I still endorse its conclusions and the kind of academic elitism so consistently supported by The Times Literary Supplement. Hofmann’s review is alone in its antagonism, as the witness from rather excellent and jobbing novelists cited on its cover shows: Garth Greenwell, Richard Ford and John Banville, for instance. Lucy Hughes-Hallett in The Guardian made what she called a ‘sedentary existence’ fashioned by Tóibín, ‘into an epic’.[3] Michael Donkoe in the i says the book ‘surely reasserts’ A Summary and Analysis of Sir Philip Sidney’s An Apology for Poetry – Interesting Literature’s ‘own status as one of our greatest living novelists’, a view later amplified by Clea Skopeliti in her interview with the author for the same paper’s weekly review and specifically addresses the issue of dependence on literal truth (the same theme about the nature of truths in art, be it noted, as in the ‘literary criticism’ of Sir Philip Sidney in 1579-80).

… but the dialogue, and, of course, the thoughts, are fictionalised. / The form allows Tóibín to avoid rigid contours of biography, and instead focus on “building up image after image … so that you have an emotional response and engagement with his life”.[4]

But if Hofmann’s critical intervention were just a disagreement about a given about the nature of literary, as opposed to literal, truth, we might rest there. Skopeliti however also allows the author to point to an important parallel in the lives, both of ‘Henry James’ or ‘Henry’ in The Master, Thomas Mann or ‘Thomas’ in The Magician and Colm Tóibín himself: their concern with the effects on the nature of truths in cases where aspects of either identity, behaviour or both are suppressed either with punitive force or collusion with prevailing powers and social forces: ‘a degree of affinity with the authors’ in ‘being “gay and from a provincial place”, adding: “I was brought up in a society where homosexuality was never mentioned”’.[5]

Now Hofmann makes a number of charges against Tóibín in his short piece, wherein little evidence not biased by decontextualised selection is used to assert them – such as that he writes ‘unimpressive dialogue’ (very soon also called ‘poor words’ that are ‘intolerably bland’ which are given ‘for them to speak’), relies on a kind of atonal recitative that is undramatic and lacks validation of what life is really like, is inaccurate about specific details of Hitler’s career and is ‘astoundingly disrespectful’ in naming authors by their first names only. It all seems rather more petty than merely elitist when read now – except that I think the core of Hofmann’s dislike of Tóibín and his literary status in the culture, does matter and it is important to call out its source. He summarises the book as something that: ‘must be little more than the periodic campy flutter of waiters and ephebes – the Queer Eye on a Straight Guy – which hasn’t been news for decades, if it ever was’.[6] The prose here is typically slippery in its defensiveness: the sentence can be read as EITHER a reference to Tóibín’s outdated views of the truth of the manners of sexual identity in public OR a slur on queer take-over of heteronormative masculine values by Tóibín and his like in contemporary culture. The Leavisites were not past making such slurs after all when they were validated by both the assumed public and legal ethos and ‘science’.

This is a surprisingly frank moment of heterosexist outrage from Hofmann in a piece that is otherwise more guarded about its underlying values. It possibly would provide meat for psychoanalysis but it it is not totally rare, although more so now than used to be the case. This is the case even in work on Thomas Mann following the revelations of his secret diaries about his sexual passions for men. For instance, Mark Harman, reviewing Ronald Hayman’s biography of Mann in 1995 for the Los Angeles Times appears to be holding back the floodgates from alluding to any actual physical sexual contact with other men experienced by Mann. He says:

In this uneven biography, Ronald Hayman, …, often draws on those voluminous diaries. Unfortunately, his presentation of this new biographical material is somewhat misleading. Instead of disclosing from the outset that Mann’s homoerotic relationships were essentially platonic, he appears to suggest, through the use of words such as lovers, that they were consummated.[7]

This is NOT a mistake Harman wants to repeat and he has already used the word ‘unconsummated’ in a context that also attempts, in its very choice of expressive language (particularly the very weighted word ‘plagued’), to explain why physical sex did not occur: ‘His doubts about this ability to achieve happiness in marriage partly reflect his unconsummated homosexual urges, which plagued him till the end of his life’.[8] The implication is clear queer sex is driven rather than motivated by the need for love and happiness and acts like a disease. Given that these words were written in 1995, they should not surprise us. Only a negative representation of same-sex love can be allowed in public academic discourse. Essentially this is the ‘Queer eye on a Straight Guy’ theme revived by Hofmann, but now in 2021 when most of us believe it either impossible or not to be acceptable to a major public organ like The Times Literary Supplement.

It is fairly clear, of course, that some of the attitude of Harman was genuinely part, at least, of Mann’s thought, feeling and sense response to his desire for men. Indeed one of the best expolorations of this I have found come from a review, in 2008, of a book by Andrea Weiss on Mann’s eldest children who were both openly queer (In The Shadow The Magic Mountain: The Erica and Klaus Mann Story) that was written by Colm Tóibín himself for the London Review of Books. This review is itself (and takes its title from this fact) fascinated by the contrast between Thomas Mann’s sexual reticence and fear with regarded to other males and son Klaus’s very full sex life. Tóibín contrast the interest in male single-sex attachment that Mann could explore only in his literary work and openly in secret journals – such that other critics now seek in the literary work that which might reveal a ‘furtive, cloaked part of his dark and exotic psychosexual being’, and Klaus’s ‘simpler soul, more open about his sexuality’. The latter in contrast had clearer anti-Fascist views than his father and acted on them from the first ‘while also managing to take vast quantities of drugs and have a great deal of sex’. Expressed by Klaus himself, it goes somewhat like this: Klaus remarked in his diary that he liked “porters, waiters, liftboys and so on, white or black. Almost all are agreeable to me. I could sleep with all of them”’.[9]

Tóibín’s tone in dealing with this contrast comes from experience I would argue – a major writer who has never made a secret either that he is gay or that it is necessary to fight for that status, or any other queer sexuality, to be recognised and acknowledged but who has always seen this fact as one of many in his self-definition. Not for him the queer novel that attempts either to pretend or ignore the fact that queerness must survive in what are often antagonistic circumstances and seek, sometimes in ways that have significance only it would seem in small groups or families, to ensure that survival in our thought about the present or the past. I would call that which must survive cognitive survival of queer life possibility rather than that overused concept and word ‘identity’. That is why I think The Blackwater Lightship is a remarkable novel and the greatest of the novels that touch on the AIDS pandemic despite its focus on the impact of a biological rather than chosen family.

But the idea of a queer novel was implicit in his early historical book on queer writers Love in a Dark Time: Gay Lives from Wilde to Almodovar of 2001. It is explored as an idea brilliantly a story in that wondrous collection of short stories The Empty Family, called ‘The Street’ (in the dark context of wider human survival in illegal immigration and asylum). His major attempt at a more recognisable, in the Violet Quill mode (see my blog from this link), queer novel was House of Names, but its setting in an anachronistic mix of Mycenaean Greek and Irish mythological material meant it appealed to fewer people than it should. The Magician takes a step further than The Master (focused on episodes from the life of Henry James) the study of different responses to living a life in which queer survival operates in stealth – emerging more often in writing, and sometimes only in issues of ‘style’ – in writers from a darker past. In Thomas Mann’s case that darkness was truly profound and included the threat of the Queer Holocaust in Nazi Germany.

Yet Tóibín continues to fight the enduring war for a contextualised queer novel, I would argue, because he is unconvinced by the argument, as indeed most queer people possibly are or ought to be likewise unconvinced, that ‘liberation’ has been achieved and is irreversible and that constraints from ultimately very dark places still press on us. And the frank homophobia of Hofmann’s critique of The Magician and The Master is actually a sign of this dark place remaining in situ in some psychologies and social reserves, even though they are at the moment not dominant. I am equally sure that Hofmann would contest that his reference to the novels proximity to being a ‘Queer Eye on a Straight Guy’ is pandering to both homophobia and heteronormativity, almost in longing for their widespread return, but he would be fooling himself if that were the case. For Tóibín actually forestalls his slur by contrasting Thomas with Klaus Mann as alternative ways of handling sexual desire between men. Queer people know that their choices of sexual behaviour remain potential to those who would wish to return queerness to being, in Paolo Freire’s term, ‘an object of policy’ in laws and the public promotion of social values of a restrictive kind.

In fact the novel is far from identifying any one gay male identity, including in its range even the appalling perversion of bodily love between men into a Nazi ideology, as in the case of Mann’s colleague Bertram:

Bertram made no secret that he had a male partner;… . … He must wake in the morning with this other man beside him. Thomas pictured their thin hairy legs entwined, their lips kissing. The image fascinated him but also made him recoil.[10]

I find that fascinating, not because it says anything about Mann specifically but it explores the mixed cognitive-emotional-and sense pathways by which queer sexual desire proresses into different forms, including the barriers set by socialised disgust reactions. In this case, the disgust will be found to be misplaced. It should have been directed at Bertrams’s extreme fascist and patriarchal nationalism. It is part of the many almost disconnected (and developmental life can only be thus illustrated) fragments of sexual development explored in the novel, not least the contribution of a peculiarly German (but not exclusively so) development of an ideology of ‘manliness’, referred to when Toibin mentions the view ordinary people too of the Mann brothers, Heinrich and Thomas: ‘not merely examples of a decline in their own (the Mann- my note) household but presentiments of a new weakness in the world itself, especially in a northern Germany that had once been proud of its manliness’.[11]

In this context various people act as exempla of how queer love survives, including family members since ‘Thomas’ confronts the fact he is able to desire his son Klaus, as well as his brother Heinrich, for whom as boys, occasionally, ‘his gaze included an element of uneasy desire’.[12] Other imagined forms of male desire for other males, of various kinds are explored, in part of Mann’s development, Tóibín would have us believe I think, in the planning of the plot and characters of prose artworks notably Death in Venice, where thoughts, feelings and sensual material related to Mann’s understanding of the composer Mahler become transmuted into Mann’s character, Aschenbach and into a form frankly much like pederasty but posed aesthetically ‘confronted by beauty and … animated by desire’), imagined around an English boy resident with his family at the same hotel as both Mann brothers and Mann’s new wife, Katia, whom observes Mann’s scopophilia with strategic appearance of unconcern, although knowing of Mann’s states of unactable desire.[13] Even Katia herself becomes a part of Mann’s queer sexual development – the emblem of being in bed with a male but not an adult male with ‘thin hairy legs’ such as Bertram sought: ‘… he imagined Katia naked, her white skin, her full lips, her small breasts, her strong legs. As she spoke, her voice low, he saw that she could easily be a boy’.[14]

Klaus’s realised sexual satisfactions with men are a very different thing than those of Thomas, his father. I indeed would say that is a given fact of queer sexualities outside the stereotypes, yet Klaus sees himself as acting out fantasies that his father had in fact invited to himself through his writing – and this relationship between the two is also part of the mix of uneven and varied development between queer men. Klaus reports late in the novel this almost as if taunting his father to be like him, in the model of widespread promiscuous sybaritic sex, in relation to ‘the subject of Death in Venice’:

”… My father was convinced that once the book had appeared, people were leering at him when he went to the opera. I had many friends because of the book, pederasts all. I didn’t have to pay for my own champagne for a year”.[15]

A ‘widespread promiscuous sybaritic’ sexual life, is also associated in the novel by Tóibín’s imaginative recreations of W. H. Auden (who actually did historically marry Erika Mann to gain a German visa and have an affair with Klaus) and Christopher Isherwood). Thomas Mann, as imagined by Tóibín, even urges on this type of public sexual life the most heteronormative of strictures: “Could you make an effort to behave like normal people”.[16] This is then a long way from the imperial rule of a gay male ideology that Hofmann insinuates by characterising it as ‘camp’ and of the cultural style of stereotypical and ‘queenly’ popular television personalities (not that I disapprove myself) such as Carson Kressley that is implied in ‘Queer Eye on a Straight Guy’. And it is a stance Mann takes in order to survive and t ask others to attempt to survive, that too is clear, and is true of moments in queer history if not a healthy queer lifestyle. Tóibín sees the contrasts of fearful restraint in the interests of survival set against sexual libertinism outside of most socio-normative boundaries as indeed Mann’s subject as a novelist, as he shows in this representation of him finding the germ of his late novel Doctor Faustus, which also as a novel set himself in direct contrast with Klaus’s best product as a novelist, Mephisto, which Tóibín had summarised as a thinly disguised novel of queer sexual liberation (in the context of frightening fascistic motivations in the case of one character based on the real actor Gustaf Gründgens in his 2008 review of Weiss mentioned above. In the same review Tóibín asserts that the other, the character Höfgen, took ‘parts of its character’ from Klaus’ father, Thomas Mann.[17] In Doctor Faustus Thomas Mann returns the favour by clearly finding an embodiment of the reckless sexual desire of one of the two doppelgängers in the novel in Klaus but only, I believe, as a means of exploring his own imagined queer and artistic life as one:

One was himself without his talent, without his ambition, but with the same sensibility. … / The other man was someone who did not know caution, whose imagination was as fiery and uncompromising as his sexual appetite, a man who destroyed those who loved him, who sought to make an art … as dangerous as the world coming into shape.[18]

For, and again I can only apply my belief that Tóibín, writes here fully as a queer man seeking to understand the diverse multiplicity of gay lives and their developments and Barriers to development, this writer too needs to understand the cognitive-affective presentation of queer lives which can develop only by bringing into interaction the world in which we all physically live and the ‘world of dreams’ and possibilities. I would further assert that Tóibín does this by playing off pictures of isolated internal fulfilment these persons might have to satisfy themselves with against a world of contradictory dissimulation (what used to be called ‘passing as straight’ in the gay world of my youth – and doubles of oneself. The problem is that is how all of us possibly actually grow but as Heinrich tells Thomas, the more we indulge a secret and ideal dream life the ‘greater the danger of being found out’.

Heinrich … was aware enough of his younger brother’s dream life to realize not only that it exceeded his own in scope and scale, but that, as he warned him, the more Thomas extended his ability to dissimulate, the greater the danger of being found out.[19]

That this double life is played out even at sixteen speaks beautifully from the story of Thomas’s schoolboy passion for Armin Martens and the poem he writes about this passion. Armin accepts that he can be the stuff of Thomas’s dream life but passes back into normative masculine-looking behaviour (playful punches) to avoid the danger of being part of the dream become reality in some future time: ‘he punched him gently … “Make sure no one finds those poems. My friends have already made their minds up about you, but it would ruin my reputation”’.[20] The game of maintain reputation underscores the fact that ‘dreams about sex’ can only make ‘their way into stories and novels’ wherein ‘they could easily be interpreted as literary games’.[21]

This isn’t to say that Tóibín accepts the view that heteronormative critics insist on – that whatever his diaries, Mann ‘passed’ as straight in ALL interactions with men and had no physical contact. That we do not know about such contact, in the context of necessitated passing of which we need to speak here, is no proof of there being no actual contact nor is seeking irrefutable evidence of such before finding how queer writers survived as queer without public acknowledgement at all an intelligent response, however academic in intention. Hence Tóibín imagines scenes such as many queer men could reproduce – the fumbling with the secretive child-relative, Wilri, for instance, which leads to a shocked experience of orgasm, the fulfilled sex with the secretive clerk, Huhnnemann, and the young body (‘sleek, white skin of the muscled back, the fleshy buttocks’) imagined by an old man of sexual ‘service’ in the description of the last relationship, such as it was, with Franzl Westermeier, the hotel waiter who appears in Thomas’s secret journals. [22] The importance of these named men is in excess of their role and ensures the survival of queer life possibility: ‘it was strange, he thought, what he remembered’, the older Thomas reflects at the end of the book as he remembers the very short boyhood episode with young Wilri, for instance.[23] And, for me, this book remains a queer classic (now) because of the fact that it celebrates the excitement queer men can find in the company of men that is bodily as well as visual without contact of bodies being at all necessary. It is an excitement i am sure Hofmann resisted, perhaps with a shudder. The episode referred to in my title is the best example of this:

The teeming commercial life of the street had its own sensuality. … most people in these streets were men. Thomas derived such pleasure from observing them …/ …. he was like a child surrounded by things he dearly wanted, an almost unimaginable richness of them.[24]

It joins those other scenes in which Thomas’ eyes play over young men’ to find one who will know, without contact, he is ‘being treated as special’.[25] It goes with the fact that even men who pass as ‘straight’ within this novel may have unrevealed experiences like Heinrich who informs his brother In Venice that it is ‘better after dark’ to take up the offer of a male prostitute from a pimp, and who thereafter:

As Thomas studied faces, including the faces of young men, many of them fresh and exquisitely alive with beauty, he wondered if they, or young men like them, made themselves available when night fell.[26]

None of my responses to this novel would please Michael Hofmann or convince him that I am not just recounting my own pleasure in the memory of what he calls examples of a ‘periodic campy little flutter at waiters and ephebes’ but then one has experienced the homophobia of people like Hofmann for too long to care. But it is a pity that he might reproduce these attitudes before lecture rooms containing some queer persons. I hope they have the boldness to call out his homophobia and examine the root of his father-complex heteronormativity. He won’t care. The privileged never do. But the queer young people will empower themselves to resist the current reaction against us.

All the best

Steve

[1] Toibin (2021: 287)

[2] Michael Hofmann (2021) ‘Mann without qualities’ (that old literary joke) in The Times Literary Supplement (September 10th 2021 – some weeks before the novel was published in UK. Ggrrr!), page 18.

[3] Lucy Hughes-Hallett (2021: 10f.) Review ‘An exquisitely balanced epic that explores the life and times of the Nobel-winning author Thomas Mann’ in The Guardian Review insert (Saturday 18th September 2021).

[4] Clea Skopeliti citing Tóibín’ words (2021: 48)‘Author’s Tale’ in life (i weekly review) 9-10 October 2021.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Hofmann op. cit.

[7]MARK HARMAN (1995) ‘Mann to Mann : Thomas Mann’s ‘furious passion for his own ego’ : THOMAS MANN: A Biography By Ronald Hayman’ in The Los Angeles Times (JUNE 18, 1995 12 AM PT) Available at: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1995-06-18-bk-14252-story.html

[8] Ibid.

[9] Colm Tóibín (2008) ‘ I Could Sleep with All of Them’ in The London Review of Books (Vol. 30 No. 21 · 6 November 2008). Available at: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v30/n21/colm-toibin/i-could-sleep-with-all-of-them

[10] Tóibín (2021 op.cit.: 125)

[11] Ibid: 11

[12] Ibid: 10

[13] Ibid: 99

[14] Ibid: 75

[15] Ibid: 365

[16] Ibid: 249

[17] Tóibín (2008) op.cit.

[18] Toibin (2021 op.cit: 334)

[19] Ibid: 7

[20] Ibid: 28

[21] Ibid: 180

[22] Ibid: 31, 65f. 422ff. respectively

[23] Ibid: 432

[24] ibid: 287

[25] Ibid: 150

[26] Ibid: 48

8 thoughts on “‘The teeming commercial life of the street had its own sensuality. … most people in these streets were men. …/ …. he was like a child surrounded by things he dearly wanted, an almost unimaginable richness of them’.[1] A blog on critical treatment of ‘The Magician’ (2021) by Colm Tóibín, London, Viking (Penguin Books).”