‘… often described as a painter’s painter’.[1] This is a blog on a visit to the Walker Gallery, Liverpool on Wednesday 29th September 2021. The primary purpose was to see a retrospective exhibition Sickert: A Life in Art. I refer in this to the catalogue of same name by Charlotte Keenan McDonald (ed. Karen Miller, Ann Bukantas) Liverpool, National Museums Liverpool.

For much more see: Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942 | Tate

The Walker Art Gallery is a National Museum as is only right but it also has some of the qualities of a very fine local art gallery.

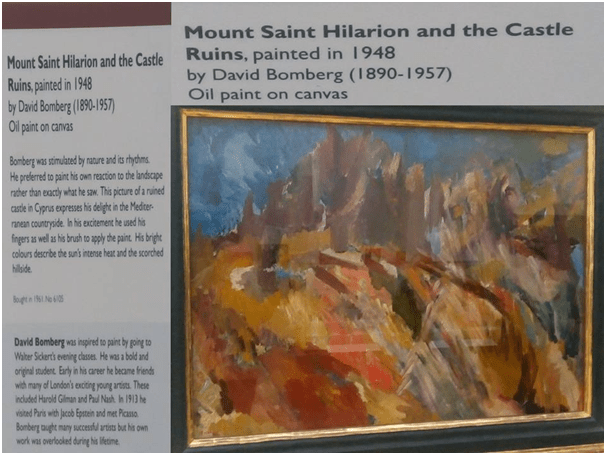

Tread into the Walker’s Contemporary Art room upstairs and you will find treasures by neglected artists including a John Minton I could not photograph properly because the highly reflective glass returned from imagery from the room than from the painting. But here is a David Bomberg, perhaps the most under-rated of twentieth century artists and not easy to see outside the Ben Uri collection, which is no longer an open museum.

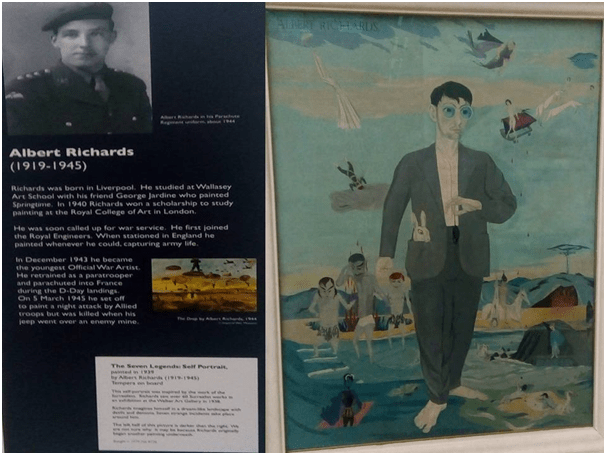

The information given is good and the painting displayed to show what an innovative colourist and expressionist painter David Bomberg was (the latter enough of a description to explain his neglect by academic art history which debunked expressionism and Has not yet redeemed it – for those who need art history at least, of which I don’t count myself one!). He is able to use patches of paint and gaps in the painted surface to convey both that this is art but that it is also a real place, home to real architecture that prompts emotion tied to cognition about, for instance the relationship between what endures and what fades. The emotion in this painting delights me. But there is an even better reason in this room for the Walker embracing its locale in the city of Liverpool – this tremendous painting by the more than neglected (nationally at least and by art history) Liverpool trained Albert Richards.

The painting here – a self-portrait – is a treat of difficult-to-read allegoric symbolism with some hints of Dante’s Inferno but a lot else as well including Richards’ favourite theme of the fall of man represented by a parachutist – he himself was a member of a parachute regiment. One could go on forever about this wonderful painting but my purpose here is just to show some of the more unacknowledged treasures of the Walker, even down to some wonderful nineteenth century classical-cum-pornographic nude sculpture.

However my husband Geoff and friend Catherine visited the Walker mainly to see a Walter Sickert retrospective, the first since the 1990s and so not to be missed. I was not at all disappointed by the exhibition or the catalogue which I had pre-ordered to pick up. Sickert emerges from the story told in this exhibition as more varied, interesting and capable of development than I had imagined and i had admired him. People call him a ‘painter’s painter’ as the author of the catalogue tells us but that does not explain that he was also loved by prose writers, such as Virginia Woolf. She recorded, or invented (these things can be very proximate) A Conversation About Walter Sickert in which her participants see Sickert as an extreme case of a writer but able in ‘silence’ to do much more than a biographer or novelist can do in words:

I repeat, said one of them, that Sickert is among the best of biographers. When he sits a man or woman down in front of him he sees the whole of the life that has been lived to make that face. There it is—stated. None of our biographers make such complete and flawless statements. They are tripped up by those miserable impediments called facts; …. Hence the three or four hundred pages of compromise, evasion, understatement, overstatement, irrelevance and downright falsehood which we call biography. But Sickert takes his brush, squeezes his tube, looks at the face; and then, cloaked in the divine gift of silence, he paints—lies, paltriness, splendour, depravity, endurance, beauty—it is all there and nobody can say, …. Not in our time will anyone write a life as Sickert paints it. Words are an impure medium; better far to have been born into the silent kingdom of paint.

But to me Sickert always seems more of a novelist than a biographer, said the other. He likes to set his characters in motion, to watch them in action. As I remember it, his show was full of pictures that might be stories,…[2]

Woolf often muses thus about the inadequacy of the main tools of her trade and indeed makes this inadequacy her topic, in comparison to painting, that by her sister, Vanessa Bell for instance (I cite her to in a blog partly about a Bell exhibition in Newcastle, using Woolf’s pregnant phrase about painters: ‘Their reticence is inviolable’). Sickert does look like the kind of person a literary person would like. Woolf also cites him saying: ‘I have always been a literary painter, thank goodness, like all the decent painters’.[3] That phrase alone would be enough to explain the long period through which Sickert has been cast aside, and his debt to visual artists like Degas pushed aside. He is too ‘literary’ and he is too English, and God forbid, too ‘bourgeois’.

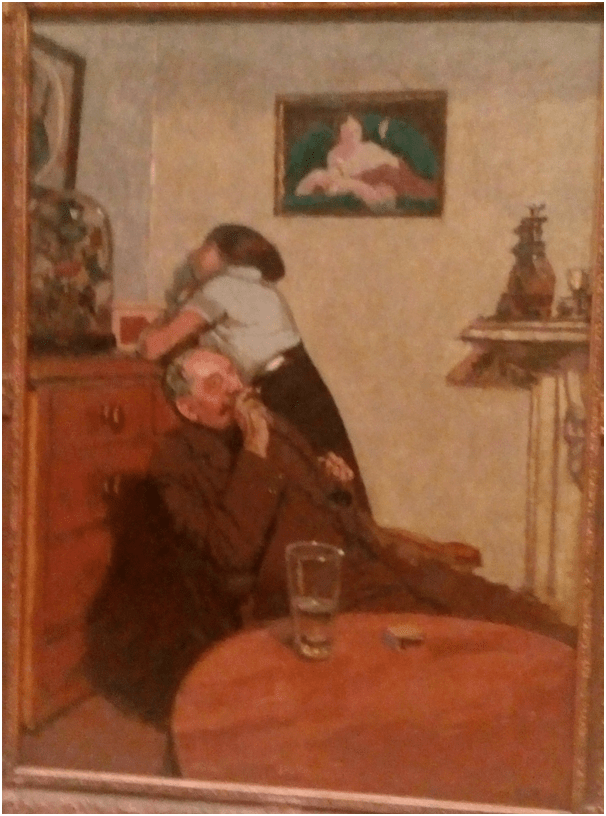

But I rather love these qualities in him because they are sources of great reflection and reflexivity in him, not least in his searing attack on bourgeois values, especially patriarchal male values that made him value the lives of bored women over their husbands, as in this famous piece.

And made him value sex-working women more than their male clients.

And made him value the working-class punters of the old Music Halls – especially ‘the boy’ Marie Cunningham loved who is ‘up in the gallery’ and is one of the subjects (never individually identified) in one of his most famous early painting. Here it is – rather easier to see in reproduction than on the gallery walls where it is sometimes effectively reduced to seeing the whites of these boys’ eyes, as might be the case in a darkened theatre. It is one of the paintings that got Sickert a reputation of only dealing with a palette of dark colours, but it is clearly spatially very innovative, not least in the use of angled and distorting mirror to double his subjects. It creates a sense of claustrophobic space here for me.

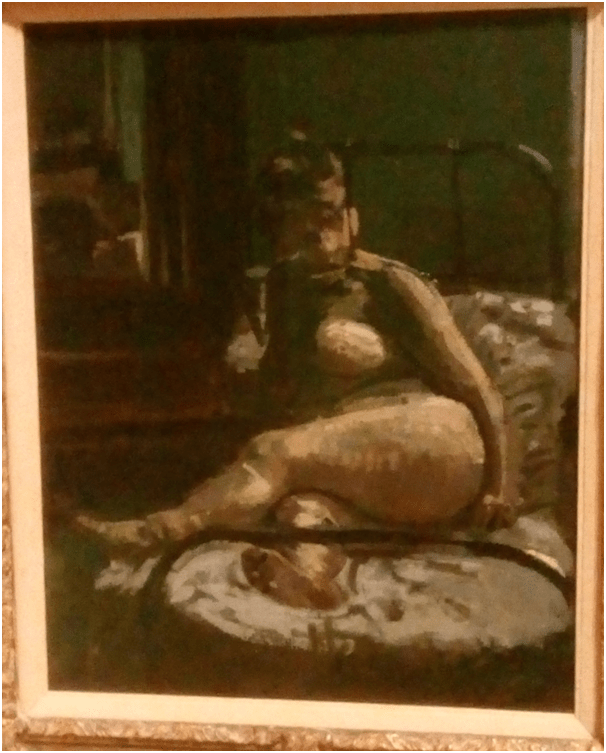

La Hollandaise also has a mirror view and mirrors are favoured in Sickert’s representation of objects and figures. I sometimes wonder why that is but I suspect that he was fascinated by the illusion of depth of space in pictures in contrast with the two-dimensional nature of the painted canvas. A mirror not only ‘doubles’ figures and objects but also places them in a contrast dimension from their solid form – useful when you need to show the reality of the sex workers flesh in some pictures including the feel of layers of fat under taut skin as in La Hollandaise.

I was particularly shaken by the various paintings in which Sickert experiments with mirrors in relation to that ultimate symbol of Edwardian bourgeois respectability – the mantelpiece, as in this exquisite painting where a woman’s ennui is part and parcel of the cluttering of body, room and mantelpiece with ‘things’. A patriarchal bust dominates this hearth and the objects glitter, presumably in the morning sun. Sickert plays with a double reflection of his space (a mirror pictured within a mirror) which suggests both the extent of the space in the room and its actual constriction. The objects on the mantelpiece contrast with their two dimensional reflection which dulls their life as presumably hers is dulled. Yet she lives, in as far as we see her face, in a gilded frame (that of the mirror reflection).

So fascinated is Sickert by this effect one piece of his shows only the objects on a mantelpiece and their reflection. This seems to intend to show the effect of framing the scene as well as flattening it, a double alienation effect which emphasises the artist’s skill in creating 3-dimensionality and the solidity of figures and objects.

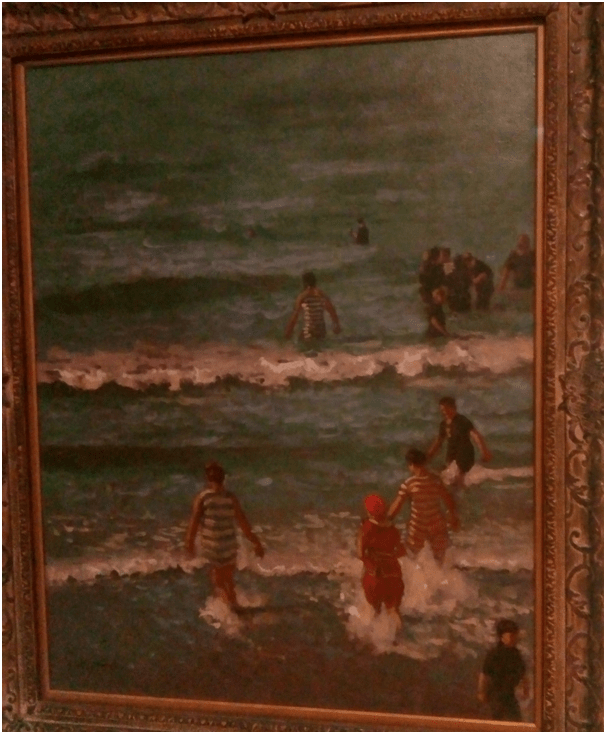

Sickert has the capacity to reflexively manifest his own awareness of what painted art entails: which I would describe as a framing and limitation of a scene whose life continues, or ought to, outside the frame and is flattened in the process other than in our acceptance of illusion. An example of how he experimented with this understanding is the great painting Bathers, Dieppe which takes an impossible view of the sea-front, situating the artist and his easel in a place it could not possibly be, in the air in front of and above his subjects, rejecting the framing and perspectival effects of a conventional horizon and vanishing point and placing itself, like the bathers, in the moving and liquid medium of the sea itself.

This is an incredible painting in part because it challenges itself to produce illusions of depth and distance without utilising the usual tricks of the painter’s craft. As formally patterned as an abstract painting the figures and waves have a kind of dynamism a mere scene painting would rob from them.

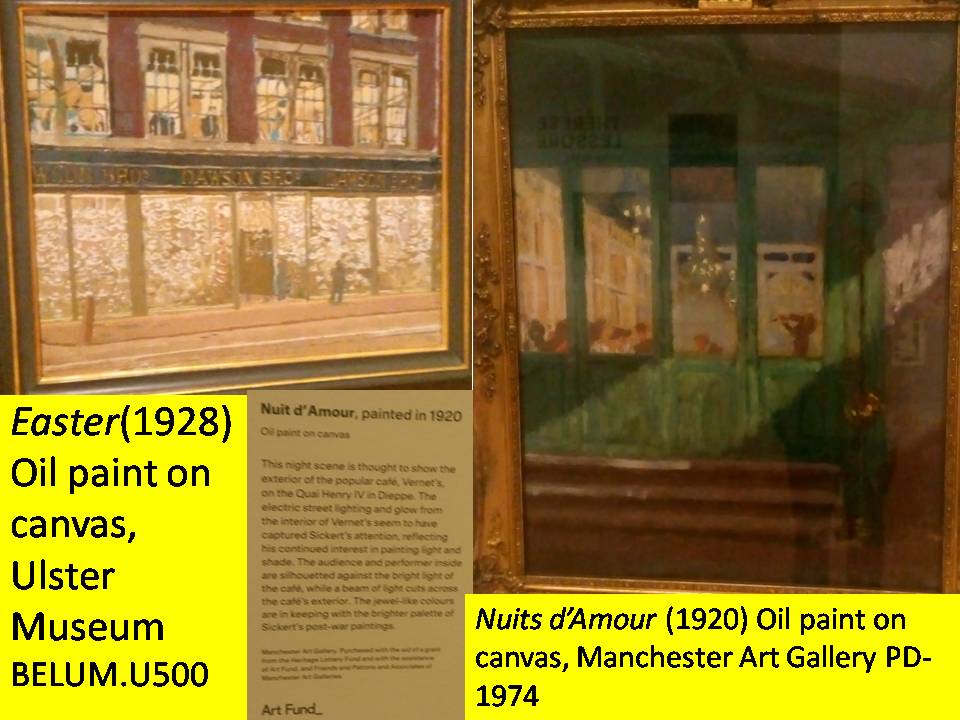

In more conventional paintings Sickert utilises the frames of architecture to create a scene that I find reminiscent of the theatrical scene painter this former actor must have been aware of. He seems to delight in how windows and doors frame a space for action even when no action is taking place on the ‘stage’ in the foreground or is occluded within an inner space. This is wonderfully true of his shop and café paintings, even the early ones but here I show two late ones from the exhibition with their bright palette of colours.

In town scenes, especially in Dieppe, buildings walls have the character of ‘flats’ on a stage setting in my view, and seem to invite the entry of characters (absent now) from many possible directions.

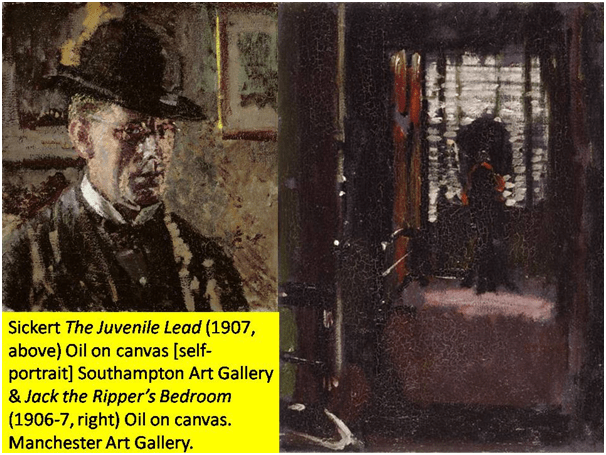

Sickert also plays games with actors in role in his figure paintings and portraits I believe, notably in the 1907 The Juvenile Lead but surely this also allowed him to utilise the shock if middle-class audiences at his shadowy residence in working class areas of Camden Town and his self-advertisement that he himself lived in Jack the Ripper’s room, making uneasy identifications between himself and a murderer of the ‘type’ of sex worker he excelled in painting.

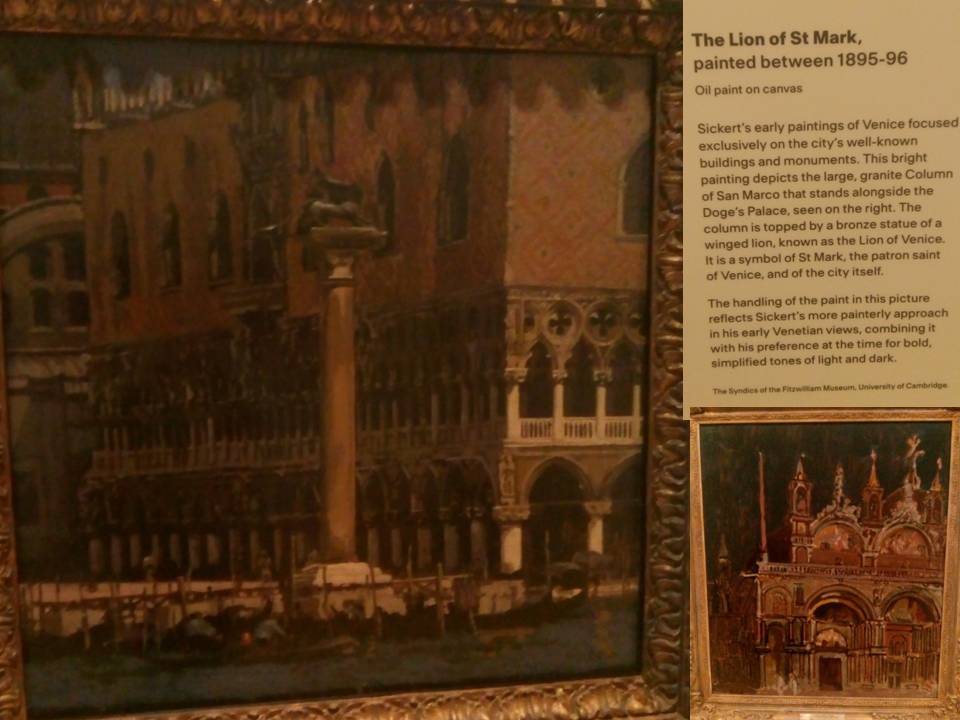

Of course we cannot leave any consideration of Sickert without looking too at how he responded to the art of the past, especially the sculptural and architectural or phenomena on the cusp of both. I believe that he is important as a recorder of past art precisely because his interests made little or no distinction between the faux Baroque of Music Hall theatres and the effects of Venetian or Northern Gothic. The interest was in the moment of capture at a certain moment in a certain light such that their effect is one of situation in a dramatised event – a viewing at end or against an extraordinary climatic backdrop of which the most stunning is probably The Facade of St. Mark’s. Red sky at Night of 1895-6. But this interest in the theatricalisation of the scenes of a dead past is so different from Monet’s practice with St. Rouen cathedral which I think is wrongly stressed as an influence in this exhibition because mood takes over from impression and/ or detail – the paintings express emotion around a building and make its appearance that of a dramatic event. I will take less obvious examples to argue this below:

The Walker has a detailed architectural drawing of St. Mark’s by Sickert probably used as a study for the inset thumbnail above of San Marco at Night (1910).[4] In comparing differences between it and this painting however, it is clear the well-observed detail in the drawing is captured in order to be deliberately obscured in the painting itself, especially the detail of the narrative art in the lunettes of the facia. The painting is deliberately off-centre in a way the drawing is not and simplifies surrounding detail of the city. This building holds us back from access to the building, , or we are invited to by-pass it on the left; even hiding the details of the doors to the basilica interior other than as the home of deeper shadows. I would guess that Sickert cares more about these emotional effects than of impressions of a building in precise conditions of light as in Monet.

This is even more the case in The Horses of St. Mark’s (1904-5) also not reproduced here. The information board for The Lion of Saint Mark (1895-6) wants us to believe that these effects are a choice of a ‘painterly’ over a mimetic effect, but I would see the essence of the ‘painterly’ here not just in ‘simplification’ of tones of light and dark but in making a medium of the way we see this artistic monument of the feelings of an artist whose relation to the splendour of Venetian Gothic is that of a later age to which such scenes have become merely commemorative of the passing of great civilisations. There is practically no detail to help us to see the Winged lion here and the mood is that of a restful ending to the day rather than of the purpose that once characterised this city. To me the mood is indicative of that in Browning’s A Toccata of Galuppi’s (1855) rather than an evocation of past art as a model for future endeavour, of a feeling that all this is past and dead; important now only as a setting for our reflections not for any other reason.

II

Here you come with your old music, and here’s all the good it brings.

What, they lived once thus at Venice where the merchants were the kings,

Where Saint Mark’s is, where the Doges used to wed the sea with rings?

….

XV

“Dust and ashes!” So you creak it, and I want the heart to scold.

Dear dead women, with such hair, too—what’s become of all the gold

Used to hang and brush their bosoms? I feel chilly and grown old.

That I read Sickert through a literary lens is possibly in keeping with Virginia Woolf and the pre-modernist subjectivity allowed range once in art. I don’t think I want to change. Resurrecting Sickert has to be the resurrection of something so much more meaningful than the canons and ‘objective values’ (really no values at all) of modern art history. It was a joy to visit this exhibition with our friend Catherine who had no previous exposure to Sickert and to see and hear her joy in the discovery of the artist, for I feel I was held back from him by the awful weight of modernist values that I obviously imbibed and introjected, as if it were innocent, in my education in both literature and art history. The Walker does a service that the following of fashion and current taste in the great Metropolitan Museums of London does not. Three cheers for the Walker.

All the best

Steve

[1] McDonald (2021: 7)

[2] VIRGINIA WOOLF (1934) Walter Sickert: a conversation Published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press, 52 Tavistock Square, London, WC1, 1934 Available at: https://www.gutenberg.ca/ebooks/woolfv-waltersickert/woolfv-waltersickert-00-e.html

[3] Cited Ibid.

[4] Ibid: 38f.

2 thoughts on “LIVERPOOL VISIT 2: ‘… often described as a painter’s painter’.[1] A visit to the Walker Gallery, Liverpool on Wednesday 29th September 2021 to see a retrospective exhibition ‘Sickert: A Life in Art’. References to the catalogue of same name by Charlotte Keenan McDonald.”