BOOKER SHORTLIST: ‘Oddly enough, there’s no name in the DSM for the compulsion to diagnose people’.[1] Reviewing this novel is like attempting to categorise the life of people of people use language that may be difficult to understand and who earn their living by making ‘worlds by the thousands’.[2] A blog reflecting on Bewilderment by Richard Powers (2021) London, Hutchinson Heinemann.

This novel has frustrated its reviewers in many ways, even those who claim that some its qualities well compensate for its flaws. Some like Susannah Butter in The Evening Standard find it ‘worthy’ or ‘preachy’ in relation to its environmental themes in a manner unfitting to literary fiction. However she also sees the portrayal of father and son – the astro-biologist Theo and his troubled son, Robin – ‘completely refreshing, original and moving’.[3] The charm of the relationship’s portrayal wears very thin for Max Lin in the ‘i’ in comparison who considers Robin’s exclusion from school ‘for smashing a schoolmate in the face’ a ‘welcome relief’ from the ‘avalanche of worthiness’ Robin’s ecological activism has spawned. He also finds the astro-biological discourse of Theo, and perhaps the ecological discourse of Robin too, to contain ‘passages of cosmic drivel’. Yet for Lin this is still the work of an ‘exhilarating prose stylist’ who can only write for the few cognoscenti of fine language and not ‘communicate with the many’ that the political themes seem to demand. [4]

In contrast again Butter finds much that is still ‘hard to follow’ in this novel, although she respects the desire to illustrate believable conversation between ‘two geeky men talking at length about facts rather than feelings, so that when they do reveal their emotions it feels more poignant’. There is at least a recognition here of the sexual politics of the novel since much that happens demands that we respect Robin’s dead mother, Alyssa, who combines science with politics and the emotional response the living world of flora and fauna ought to raise in us. Not that this engaged feminist slant impresses Adam Roberts in The Guardian. He too finds that the novel fails because it does not attempt to meet the aesthetic requirements of a novel or great tragic Greek art because of its one-sided, in his view, and over-zealous commitment to environmental political activism. He says:

… activism is one thing, fiction another, and Bewilderment is unable to conceive of anyone except the wicked and the ignorant failing to join Theo and Robin in their intensity of belief.

Drama needs a little more of the old Antigone dialectic, more of that balance of conflicting forces.[5]

Some readers, of which I am one, will balk at the assumption that Powers fails because his art does not recreate the dialectics of Sophoclean tragedy, especially when Roberts seems confused, a confusion for which he again blames Powers, about what kind of literary project this is. He plumps, I think but does he by using that slippery formulation ‘can be classed’, for science fiction:

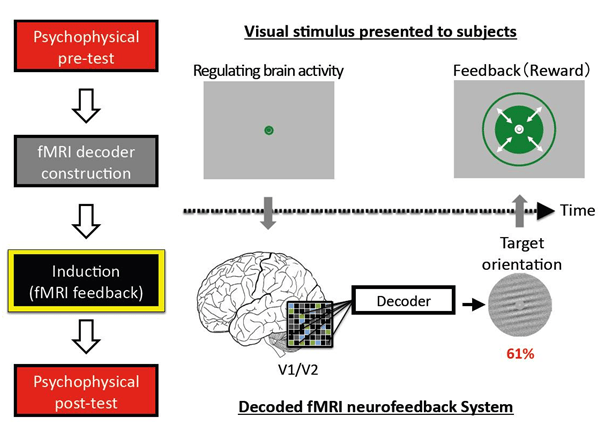

… not just in its extrapolation into a dystopian future, or Theo’s detailed accounts of possible life on other planets, but because of the main story device: a technology called Decoded Neurofeedback. AI-mediated neural imaging, this enables people to “approximate” the neural structures of other people’s brains.[6]

So far, so unclear then about how we actually categorise this novel or at least those parts Lin found ‘cosmic drivel’. At least Roberts however nearly reaches characterising another element of the novel which is a deep connection to the discourse of health, and not least the so-called ‘science’ of diagnosis. He really only captures the fact that diagnostics appear both to matter and equally not to matter in this novel, when he say:

“So far,” his dad notes wryly, “the votes are two Asperger’s, one probable OCD and one possible ADHD.” Theo loves his son intensely and refuses the medication regimen urged by the authorities. “He’s nine years old! His brain is still developing.”[7]

Of course such dilemmas are vitally important in the life of parent carers such as Theo clearly is – a man whose responsibility for his son exceeds that of most fathers because it must take in the knowledge, skills and values of the medico-psychiatric system and its discourses. And it’s my view that nowhere does Powers come nearer to showing us the problematic in the creation of peopled worlds in creative fiction that critics often grossly oversimplify. That is certainly the case with the examples I’ve looked at thus far. Critics like psychiatrists make their judgements by classifying a work or a patient within a catalogue of ontological possibilities, not of their own making or totally under their individual power of definition, and then compare the qualities of the former with the standards of the latter. It is rare that acts of reading or hearing the words of work or patient themselves are used to check the assumptions this process of elite critique involves. The equivalent of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (currently in its 5th heavily revised edition – DSM for short) for diagnosing the literary work is the ever-expanding and self-interpreting canon of great Western world literary works.

And I would find an analogue in this novel between Theo’s concern to query those who do the classifying before accepting their authority or that of the canon they habitually use. Theo says: ‘Oddly enough, there’s no name in the DSM for the compulsion to diagnose people’.[8] For it is not only psychiatry but social norms over a wide range of domains that demand that we classify and label people, behaviours, human articulations in an unquestionable order that we like to think of as representing certainties about the world. A better critic than any of those I have looked at thus far is the young novelist (although he also teaches at Nottingham University) Ben Masters, who reviews this novel for the Times Literary Supplement. He uses an approach that refuses assumptions about a canon that necessarily sets an external standard for literary art and begins his review by discussing the concepts in the novels themselves, analysing how they vary from their accepted meanings we might otherwise apply to them.

It is refreshing to read that we should examine a work perhaps by reading very thoroughly the contexts in which any particular writer ‘gravitates towards particular words and images that reveal at least something about their preoccupations and their work’s affect’.[9] Even better that Masters, whilst acknowledging if not taking much further, that though the word ‘bewilderment’ is:

‘hardly used at all, the bewilderments of Bewilderment oscillate between the kind that are implied powerfully through the actions and sensibility of the narrative and the kind that are told and named for us’.[10]

There is a masterly reader at play in this example of good literary criticism which contrasts the effect of a novelist as a writer of interacting statements and descriptive effects and the novelist who creates plot that works within the characters as well as external to, and between them. At last a critic who recognises that complexity. Now I think Masters lacks the space in this piece to really develop this complex reading of how this novel works, but his analysis of how the concept ‘bewilderment’ is developed in earlier novels suggests just how complex it is.

“Bewilderment” (“confusion arising from losing one’s way; mental confusion from inability to grasp or see one’s way through a maze or tangle of impressions and ideas”, according to the OED), along with its loose synonyms, is a useful word-key for unlocking Power’s oeuvre. In The Overstory, where the species of a Brazilian forest “clog every surface, reviving that dead metaphor at the heart of the word, bewilderment”, it acts as a resonant metaphor for the novel’s various entanglements and perplexities, and for the sublime.

Since I have not myself read The Overstory I cannot personally verify the perception in the last sentence, however as a pregnant approach to Bewilderment itself it’s a wonderfully rich way of looking at the novel. It is one I would use even where I disagree with Masters’ own applications of it to the last novel. And it is from this approach i will try to summarise my experience and judgement of that novel since its very focus is on uncertainty not classification or simple labelling diagnosis (it’s appropriateness to the criteria of a label) of Powers’ invented world in the novel. Of course we have to take into account that Masters’ assessment of Bewilderment, like the others apart from Butter, finds Bewilderment the novel a disappointment even by the standards of setting a criteria of ’bewilderment’: creative and ‘sublime’ forming of near formless ‘various entanglements and perplexities’ into a novel. For Masters find this novel ‘overly neat and almost clichéd about how he treats the running cosmic theme’ and that ‘simplifying orderliness might have just won the day over the tangled, confused and labyrinthine: an aesthetic weakness that undermines the titular theme’.[11]

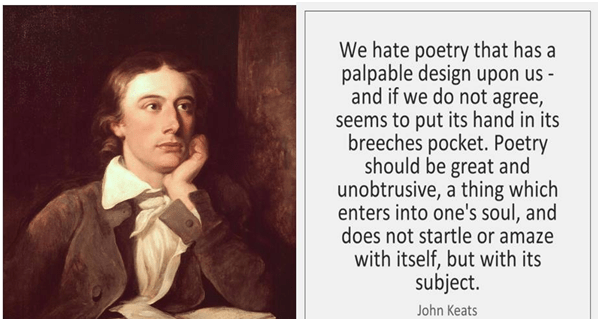

So here again a critic finds this a weaker novel than it might be and partly because it speaks to the themes of the politics that ought to matter to many people and not those with an appropriate education. In the end I suppose Masters just tries harder than the rest to hide his distaste for political commitment; except, what Roberts article, in his title only calls a damning ‘didacticism’, Masters calls by the nearly synonymous terms, ‘tidiness and instruction’. The standard here, always used to deny the right of true literature to address political action and almost echoing in the ears of the educated elites is Keats 1818 statement: ‘‘We hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us, …’.[12] In the end, I insist, it takes a lot for criticism to give up its role as the policing psychiatrist of either the canon of great literature or its apolitical assumptions, enshrined in great literary critical statements like that of Keats.

Now I am not going to say this is an absolutely flawless and perfect novel, nor that it should win the Booker (I think it should not) but that is not because of its urgency about how we imagine our duties to the planet we inhabit, by imagining other counterfactuals in invented planets, nor because its ‘preachiness’ is set in the context of real debates between combatants like the late President, Donald Trump, and Greta Thunberg. The latter appears thinly disguised in the novel: the latter as Inga Alder; the ‘oval-faced girl in tight pigtails’.[13] The right wing president pictured in this novel defunds educational projects in the name of their supposed radical affiliation. There is no doubt, of course that it is possible to read the novel as entirely situating itself on the side of Alder’s (and hence Thunberg’s) activism and against Trumpism. So much so that the rather acid analysis of Max Lin is that the politics of the novel is not oversimplified but contradictory: ‘His surprising resistance to doctor’s advice means you could read him as a symptom of our age’s twisted attitude to expertise’.[14]

But only someone who knows very little about the politics of mental health can say that Powers’ view against the blanket use of psychiatric medication and psychiatric labelling of the Kraepelinian type is ‘surprising’ – it is part of a much larger political movement, dismissed because the victims of poor mental health care are dismissed as already ‘mad’. This is one reason why the latter movement embraces its madness and calls itself the ‘Mad’ movement, a movement of which I and survivor-experts like Peter Beresford agree. But no witnesses apart from those in the literary establishment are allowed in the Western English literary tradition as supported by say, the Times Literary Supplement, but not only that august organ, at its worst. For if a novel cannot point out that psychiatry may be sicker, and make people sicker, than the people it purports to assist, like Robin, for its adherence to an oversimplifying ‘medical model of interpretation except of itself then it is being bound by a politically conservative force that refuses to see complexities in the political and creative process.

For Powers’ narrator, Theo, although he may be an astro-biologist, is also a creator of artefacts that have the character of art. These artefacts are called ‘worlds’: ‘I made worlds by the thousands’.[15] Like that of an artist, it’s a job almost impossible for a boy to explain to his father’s job to his school-mates. I don’t think the view that partisanship in environmental or other politics works in attacking this novel, especially given the novel’s honestly confused and bewildered intelligence about mental health diagnosis is it rank to call its politics, as Max Lin does, a ‘symptom’. For critics are not guardians of our physical, mental or spiritual health and, as long as they see art as removed from statements about necessary change in political direction, they are not even seeing creativity as a function of ‘living’ in the world but of being sequestered from it. The worlds Theo invents are like philosophical thought experiments and such experiments are what great art consists of – why, for instance, we can speak of Jane Austen’s, or Keats’, ‘worlds’. I don’t think I want to argue this in detail but it is already suggested by some of the names of the worlds to which in imagination he takes his son (page references listed in footnotes: Dvau, Falasha, Pelagos, Geminus, Stasis, Tedia, Nithar, and Similis.[16] Even the past states of our world are to Theo predictable as counterfactuals.[17]

And, if anything I find this novel a defence of the kind of autism that art is in part. It’s a plea by all novelists when they imagine their critics or by people labelled mad by their doctors:

What’s the use of simulating so many worlds, many of which will not even exist? What’s the use of preparing targets beyond the ability of current instruments to detect? To which i always answered: What’s the use of childhood? I was sure the Earthlike Planet Seeker … would come along …. Sand from these seeds, the wildest conclusions would grow.[18]

There, in my view, is the book in a nutshell. Bewilderment is an artistic project to sew the ‘wildest conclusions’ for which the normatively rational will not find a use, but which our humanity MUST find a use, like it attempts in increasingly rare places, to value childhood in itself and not as merely a Gradgrindian, if more subtle than Gradgrind, preparation. And no-one amongst the critics I have cited seems to honour this view or to notice the prominence the book gives to poetic language, even when it is just read to your dog Chester, and specifically to W.B. Yeats. What do these critics read when they read the Yeats stanza cited near the end of the book. It is certainly not anything like the message of a poem, A Prayer for My Daughter) asking us to be bewildered again, for a purpose.

Considering that, all hatred driven hence,

The soul recovers radical innocence

And learns at last that it is self-delighting,

Self-appeasing, self-affrighting,

And that its own sweet will is Heaven’s will;

She can, though every face should scowl

And every windy quarter howl

Or every bellows burst, be happy still.[19]

For it is the opinionated who look down upon confusion and bewilderment. That urge to bewilder rather than ratiocinate, which skill art must still claims for itself, is valid. Even Robin doesn’t ‘get’ that poem when read to him by his father but he is given it anyway since ‘getting’ a work like that is not the point perhaps. Having said that, predicting Booker winners is a matter of opinion and like these critics I do not think this is the novel that should win. But that is not because Powers wants to explain why he lives his life secluded in the Smokies in defence of the process of wilding the over-sophisticated urban intelligentsia in the academies but because like Robin we still need to remind people that life is finite and more so, if its value is not recognised in appropriate action.

All the best

Steve

[1] Powers (2021: 5).

[2] Ibid: 64

[3] Susannah Butter(2021) Review available at: https://www.standard.co.uk/culture/books/bewilderment-by-richard-powers-book-review-b956211.html

[4] Max Lin (2021: 52) ‘A perplexing tale of eco jeopardy’ in the i 24th September 2021[5]Adam Roberts (2021) ‘Bewilderment by Richard Powers review – environmental polemic’ in The Guardian (online) Wed 22 Sep 2021 09.00 BST. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/sep/22/bewilderment-by-richard-powers-review-environmental-polemic

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Powers (2021: 5).

[9] Ben Masters (2021: 16) ‘Chemical bonds: A novel of universal wonderment – and paternal love’ in The Times Literary Supplement No. 6182 (September 24 2021), 16.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] See https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69384/selections-from-keatss-letters#:~:text=We%20hate%20poetry%20that%20has,itself%20but%20with%20its%20subject.

[13] Powers (2021: 121)

[14] Max Lin, op.cit

[15] Powers (2021: 64)

[16] See ibid: 14, 37, 61, 84, 113, 151, 205 & 232 respectively.

[17] Ibid: 26

[18] Ibid: 64f.

[19] Yeats cited ibid: 241

One thought on “BOOKER: ‘Oddly enough, there’s no name in the DSM for the compulsion to diagnose people’. A blog reflecting on ‘Bewilderment’ by Richard Powers (2021) London, Hutchinson Heinemann.”